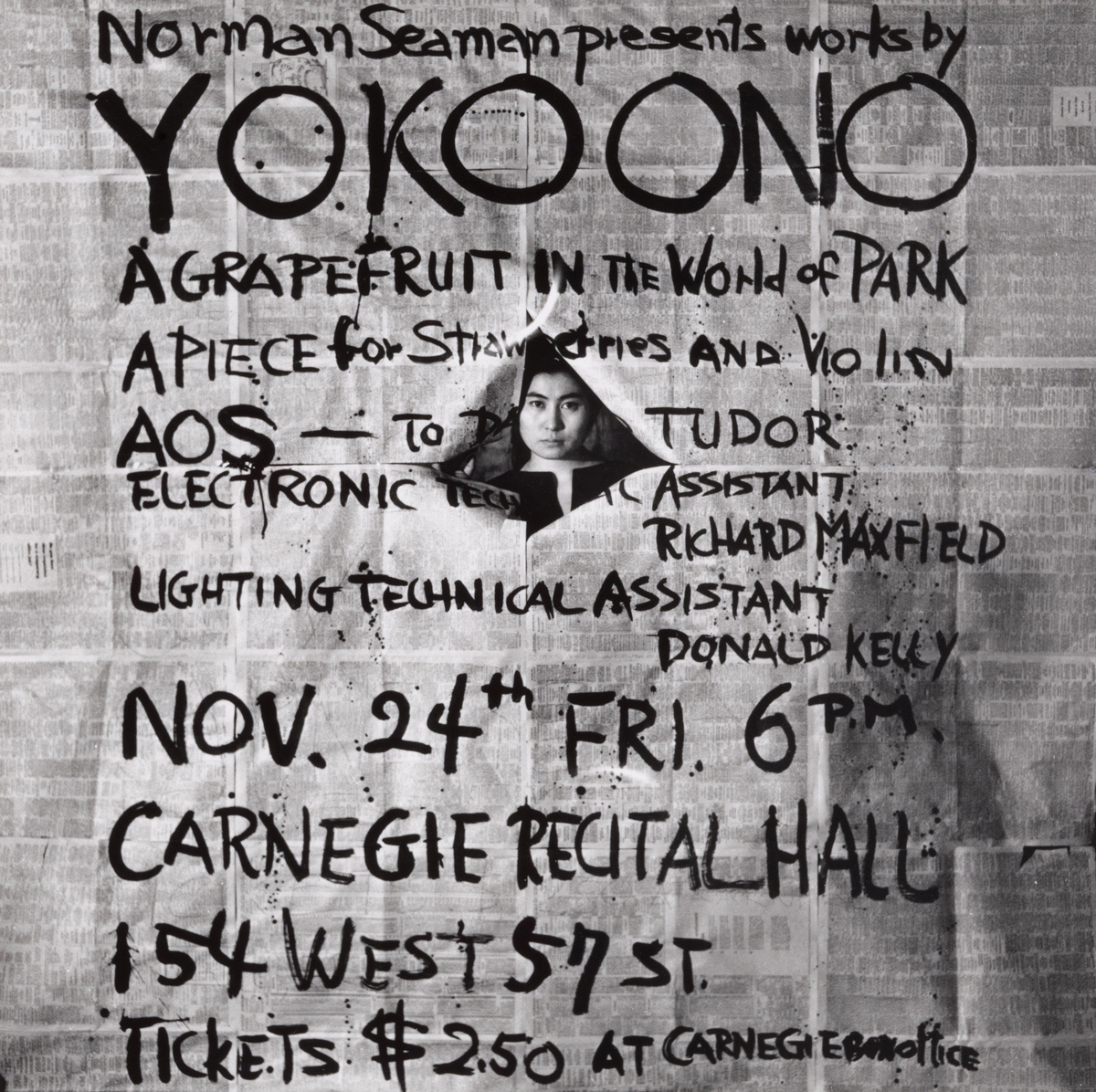

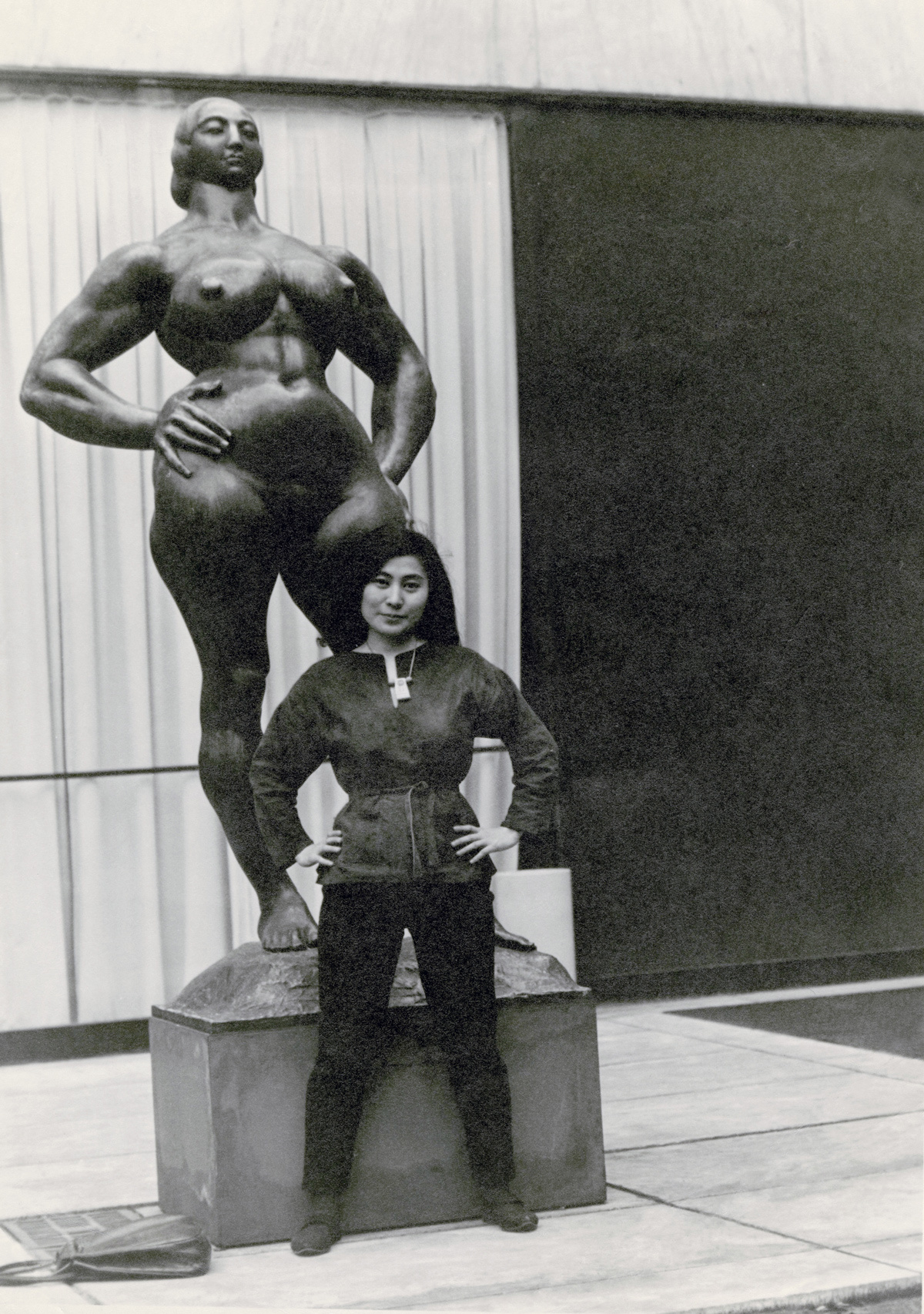

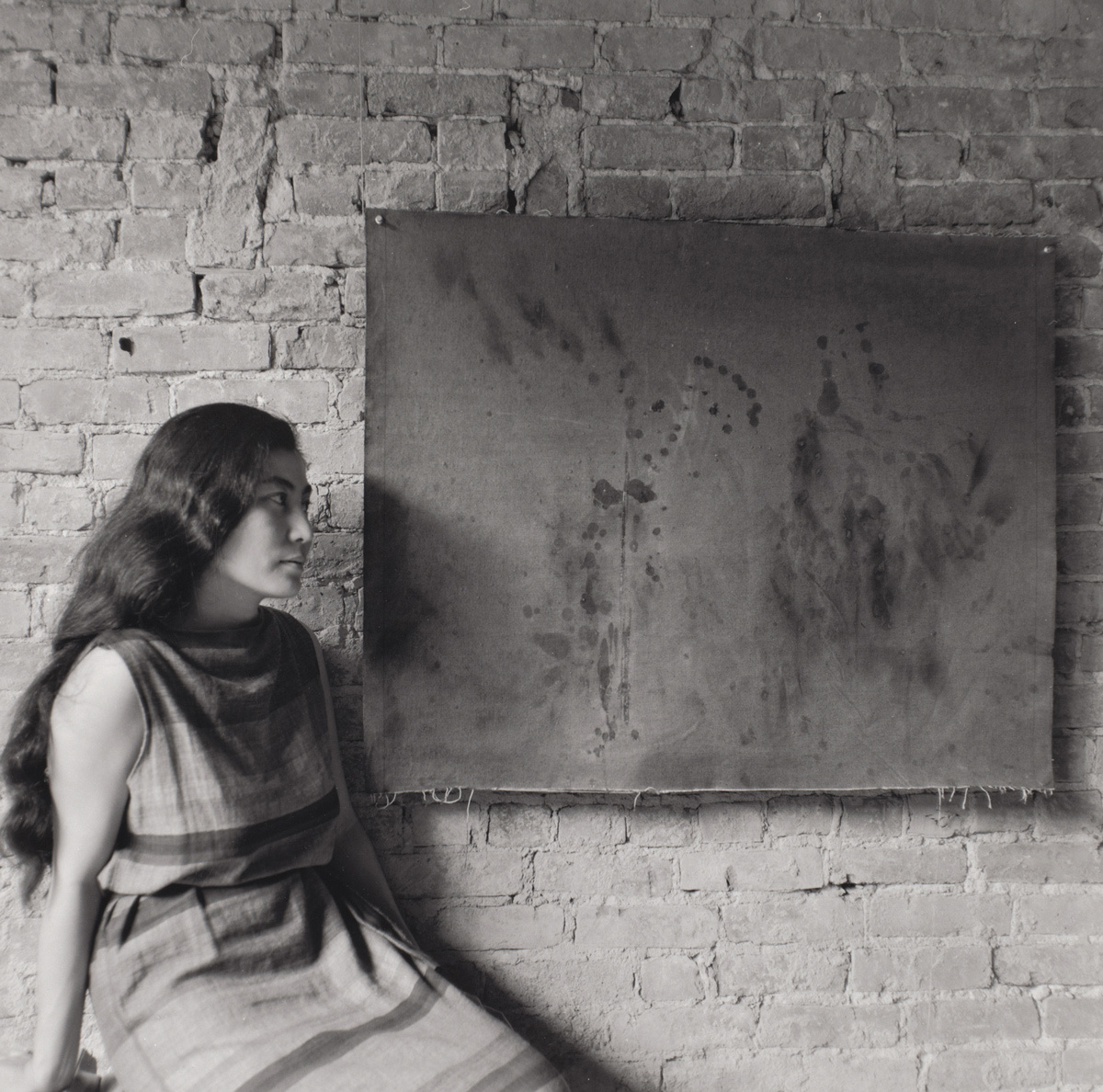

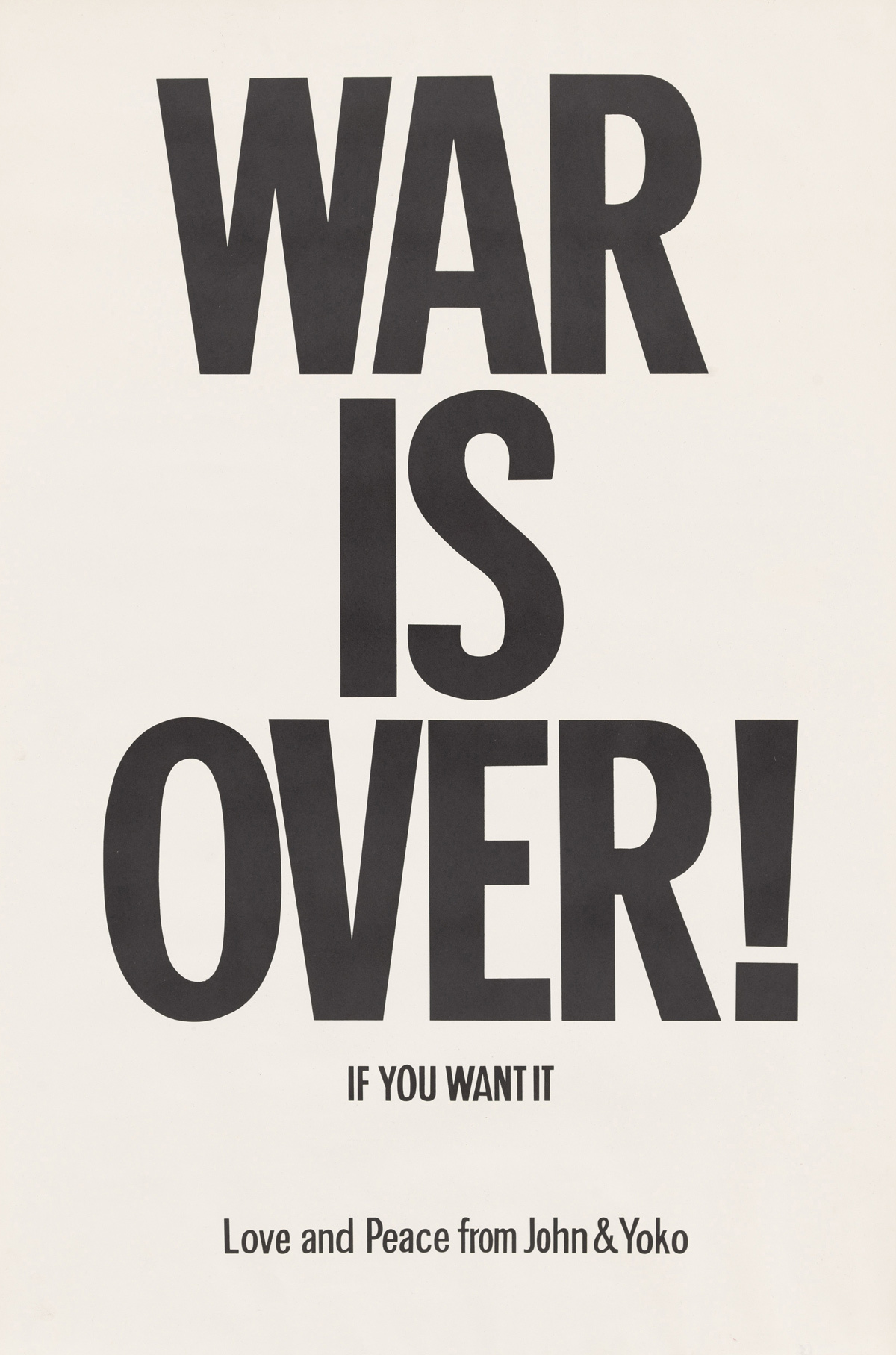

A young Japanese woman stands impassive, wearing the simplest clothes, as members of the audience enter the picture with scissors, trimming off bits of her garments until she stands exposed before them. This is Cut Piece, now seen as one of the foundation events of performance art, and taking pride of place in MoMA’s Yoko Ono: One Woman Show 1960-1971 – a gathering of film, performance, print and sound work old enough to be your mother, but imbued with a radical freshness that still dazzles and shocks as if born yesterday. Because she has carried themes of peace and understanding through a lifetime’s work—and because she worked with ephemeral, fleeting moments long before we learned to capture them with modern technology or understand what made them into works of art—it’s as if a long arc of justice has looped back to favor her, delivering this timeless 80-something the status she’s always deserved.

Yoko Ono was always about more than an extended game of rock star-paper-scissors, and always deserved classier treatment than having her reputation trashed by Beatles fan-boys who irrationally (and misogynistically) blamed the artist for the demise of her late husband’s band, and point-blank refused to respect her as an artist in her own right. But rock critics are often the last to know about art outside music, and among the first to close patriarchal ranks around women’s creativity. Although her practice can seem theoretical and lighter than air, it is in fact visceral and suffused with a grounded-ness the rhetoric around her private life never quite managed to obscure. For nearly 50 years, the myths surrounding Yoko Ono have been potent distractions, indicative of the sexism and racism of her critics and our times. Today, it’s time to go back to the work.

Yoko continues to ask her audience to actively engage with her art and each other in equal measure, promoting ideas of connectivity and interdependent actions that seem natural to everyone coming of age in the 21st century. I’ve never emerged from one of her exhibitions thinking something was missing, or misplaced. Her interventions—whether as a solo artist or as a part of FLUXUS, the 60s-born international network of artists working across borders and disciplines—have always tried to expand the public’s art consciousness through encouraging a less passive relationship with things created by others. Although she’s been a New Yorker since 1965, her work will always reflect her Japanese sensibility, and has always suggested to me a secular form of Shintoism at play. The ‘old religion’ of Japan, which predates even Buddhism, Shinto asks adherents to invest in the idea of god being in all things; Yoko Ono’s work asks us to imagine art in the same way. Precise and often minimal, her interventions always build into something greater than their initial act.

My favorite Yoko Ono myth, like many of the others, isn’t even true—but unlike most of the others, it probably should be. While a young woman, Yoko was an undergraduate at Sarah Lawrence College, an art school just outside New York City with a non-traditional approach to curriculum and grading, and a reputation for attracting some of the world’s most creative people before the world recognized their genius: JJ Abrams, Win Butler, Girls producer Jenni Konner, Julianna Margulies and Alice Walker were all students there (as was I). At SLC, there were dances with DJs most Saturday nights (in my day, five years before his music laced every advert going, our decks belonged to Moby); refreshments laid on for tired dancers included a fully stocked ice cream bar. Somehow a rumor took hold: the ice cream was really a FLUXUS intervention, endowed to the college in perpetuity by Yoko herself. This fanciful notion enhanced our sweaty midnight revels, and offered us a chance to find art in a place we hadn’t seen it before. Even if Yoko Ono never put the ice cream in the dance hall, she opened us up to seeing how this could be art – with a cherry and some sprinkles on top.

Yoko Ono: One Woman Show 1960-1971 is at MoMA until 7 Sept

@suzycorrigan

Credits

Text Suzy Corrigan