Being a fashion photographer between Berlin and Paris sounds glamorous. For Henrike Stahl sometimes it is. But Henrike prefers to reevaluate what photographing in capital cities looks like. She often shoots subjects in the northeastern Paris suburb of Seine-Saint-Denis (“le 93”), a much-maligned outskirt she has long enjoyed living in despite its widespread ‘bad reputation.’ She also amplifies her photographic practice through aesthetic gestures, experimenting with oil paints, and transforming photos into fabrics.

Her work is currently on view at Portrait(s) festival in the French city of Vichy. This year’s poster features one of her images, and her work opens the group presentation. Prints are hung on wallpapered backgrounds or draped as soft textiles, alongside a collaboration with art director Éric Poupy. We spoke with Henrike about advocating for misrepresented urban spaces, the era of OD’ing on Photoshop, and Wolfgang Tillmans’ impressive longevity.

What led you to photography?

I started as a photography assistant when I came to Paris almost 20 years ago. I grew up in the countryside in a really small village. My father is a math teacher; my mom sells antiques. When I was traveling at 16, I saw exhibitions featuring Rineke Dijstra, Nan Goldin… I got really into their work, and I wanted to do that myself, so I took my dad’s camera.

When I started, everything was still analog. Then came digital, and then there was Photoshop. People started to really retouch and transform photos. There was a whole period—like, five to 10 years—where everybody explored this. We all, I think, have parts in our history we wish we could remove… I requested Google remove some images with filters. We wasted some time exploring this way of working. I stopped fashion, for a bit, because I wasn’t into retouching. Then I started to shoot again, working with non-models and people from the street— what I did before Photoshop. Now I’m back to what I did 10 years ago.

At what point did medium-mixing happen? Are those hand-done or digitized superimpositions?

I do touch up my pictures a lot now, but it’s cutting out or painting on. I hardly retouch on Photoshop. I don’t try to make people ‘more beautiful’ on the computer. I’m not trying to take away parts of people, I’m trying to take away parts of the photo that I don’t really want to see anymore. I try to change the ambiance of the picture.

You’re treating photographs as material that you can continue to play with, rather than completed work. Like the pink and green overlay on the image from Kenneth Ize’s backstage, for example.

Yeah — this one was done on the computer because I painted on really big. Sometimes I draw by hand, and then I scan. Other pictures I’ll oil paint directly onto the prints. I’d been working for a hotel chain for a long time; on some pictures I did, I wanted to take away the blue sky because I thought It’s too commercial. So I just started painting on the sky. That was how I started.

As a modification, it’s subtraction, as opposed to addition.

Yeah.

You shoot for magazines and work on personal series, but you mix them together on your website. How much do these overlap?

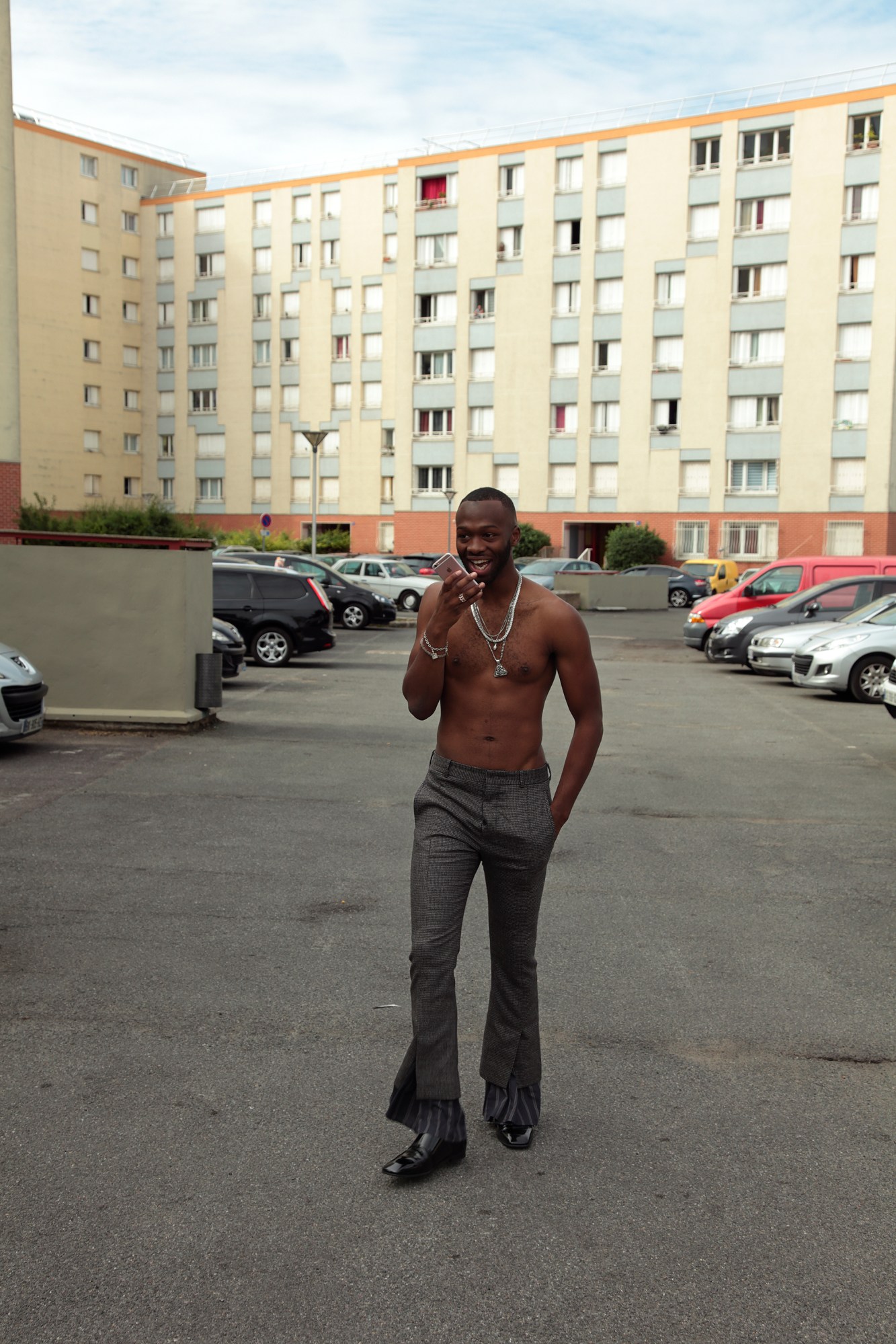

For my series “Mon Roi,” I wanted to talk about people from the Paris suburb I live in. Sometimes I take pictures for a fashion story to do other things with them, but there’s a through-line. So they work together.

How often do you work with non-models?

I’ve been working with non-models for a long time, like since the early 2000s. I had a disabled daughter who came into the world—and I had problems with this “perfect” way of seeing people. For me, everybody is worthy of being in a picture.

The first picture for “Mon Roi” was the guy on the horse with the helmet, named Gamart. I saw a video of him on Facebook, riding his horse with his helmet on through the Paris suburb of Montreuil—somebody had filmed him from a car. I felt like: I need to shoot a story with him. I asked him if he would do a fashion story with me for a magazine. He wanted to, but he got into trouble and his horse was taken away by the police. So we got a friend’s horse to re-create what I had seen in the video. It’s staged, but based on real parts.

There’s this contradiction of people being very wary of Parisian banlieue— but then certain style elements stemming from there have become increasingly mainstream. Do you think the relationship to the suburbs is changing, or is it just a short-lived trend?

I photographed the guy with the dangling earring [from the 91 suburb] in my house in Aubervilliers. He’s one of these guys that got exported from the banlieue to—all of a sudden—fashion shoots and shows. For me, the danger of these areas is overly emphasized. The area is changing, but I’m afraid interest in the banlieue is just a trend.

When I exhibited “Mon Roi” in Arles in 2018, people from outside Marseille told me they were happy that I showed a different view of the banlieue, that other people might distance themselves less. People from the French countryside told me: Oh, we’ve never seen the banlieue this way. We would never have dared to go there.

For me, the banlieue was closer to the freedom that I had in Berlin — empty lots, open spaces — somehow I really felt at home. It’s changing here now; they’re building more and more skyscrapers.

How does being between Paris and Berlin shape your aesthetic? They’re very different cities and cultures… How do they feed each other?

At the beginning of my career, Paris was where I earned commercial money; Berlin was where I had my artistic work, and partied. I could easily live with the money from Paris in Berlin. So I had a beautiful life in Berlin, and I had all of the quality of work that I could do in Paris. It was good to have Paris because there’s something called the “artist’s syndrome” in Berlin — where you don’t work, you just party all the time. In Paris, you have to work a lot to live well. You don’t need to in Berlin. Today I’ve found a good mix. Here in the suburbs I’ve got open space, I’ve got trees — I can live more easily than in Paris’s center.

Can you talk about that beautiful black-and-white portrait from Off White?

That was Virgil Abloh’s collection in 2019 that I shot backstage for [French newspaper] Libération. It looks a bit like pictures from back in the day—it could be from the 1970s. During fashion week, it’s an exercise to work so quickly, because I have like 10 images to do per show and there’s like 10 shows per day and you have to deliver everything on the same day or in the evening. You have to work really quickly.

It looks like a very calmly-made studio portrait; you would never guess those circumstances.

The privilege of shooting for a newspaper is that they don’t really need to show the clothes—they just send you there to take nice pictures. [laughs] You find your own signature in a space you didn’t create, created by stuff already happening. You can change the light a little bit, but not that much. So you find something in there that is nice for you.

You mentioned earlier the influences of Nan Goldin and Rineke Dijkstra. Are there other photographers whose work was meaningful to you, or exciting to follow?

Well, Wolfgang Tillmans. He’s, for me, an example of the guys that we liked in the 1990s or 2000s—yet he keeps making nice images today. Other photographers, when they started 20 years ago, Ellen von Unwerth or people like that, they had a certain style and at some point you… can’t see it anymore. Tillmans, or Nan Goldin, you keep watching them. They stay close to the real person. There are also really talented young photographers out there today… I love the work of Nicola Lo Calzo, for example.

Regarding the way photographers evolve over time—do you feel like you’ve maintained an aesthetic long-term, or have you had different ‘eras’ in your own work?

It’s taken me a really long time — almost 20 years — to get my career going, because I was very hyperactive. Normally, you have to choose one thing and people know you’re there for this thing. I never did that. I always needed to be able to touch on everything. So I’m doing commercials, I’m doing portraits, I’m doing artwork, I’m doing fashion… I need to be able to jump from one thing to another, or I would get bored.

As someone who is also unfocused and interested in lots of things, I relate.

It’s good to do what you haven’t done before.