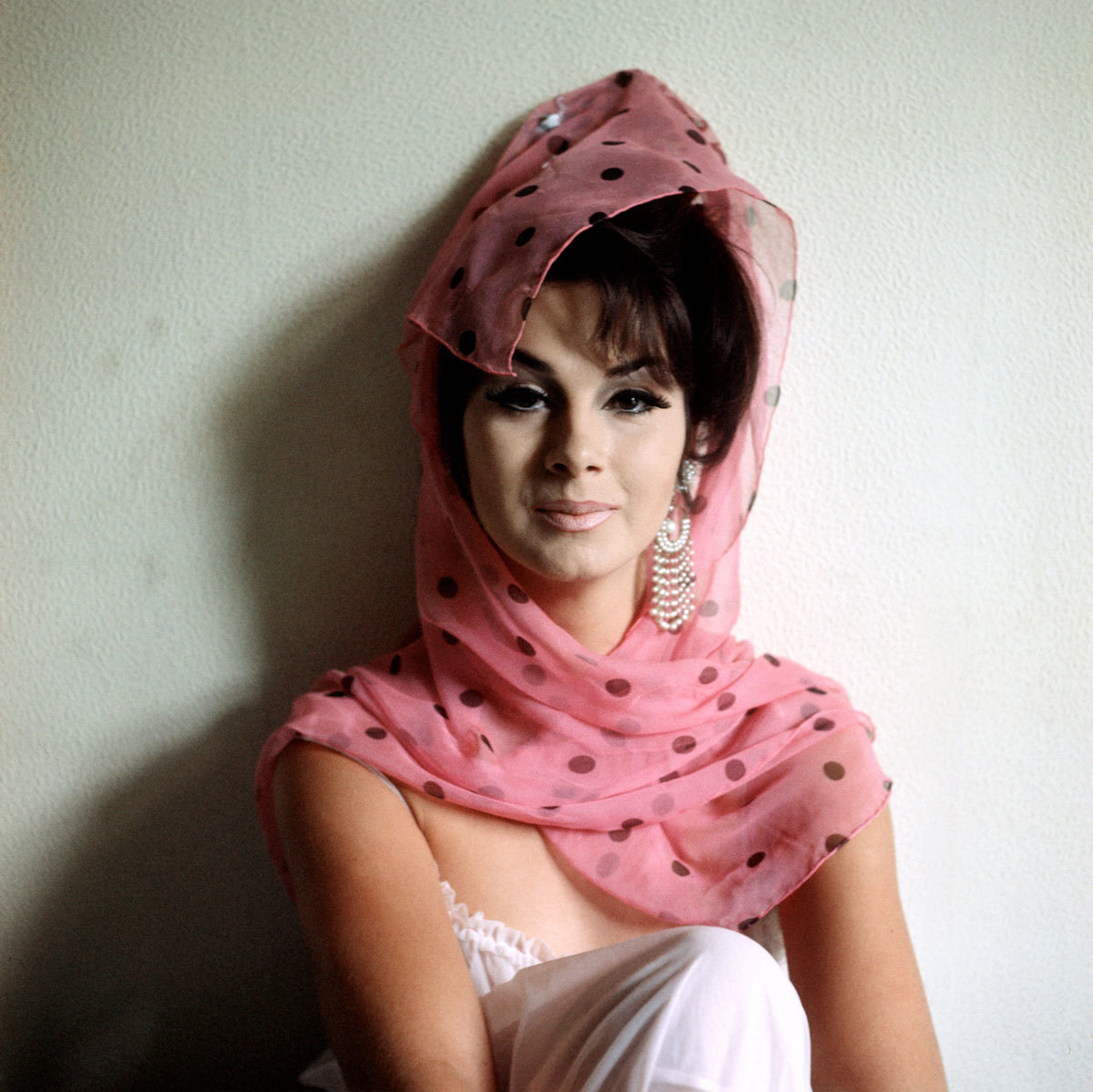

You could be forgiven for thinking that Laverne Cox and Bruce Jenner were the first transsexuals to make the headlines. But decades earlier, April Ashley was a high profile socialite who helped pave the way. In 1960, at the age of 25, she underwent risky gender reassignment surgery in Casablanca. Her career saw her host the famous Le Carrousel de Paris, and David Bailey photographed her for Vogue. April celebrates her 80th birthday this week by being named a “Citizen of Honor” in her home city of Liverpool.

At a restaurant on the Fulham Road, near where April Ashley lives, she tells us, “We caused quite a fuss when I came in here with Eddie Redmayne. Apparently, I danced with his father at Tramps in the 70s. I must have been quite pissed because I don’t remember dancing with anyone. I don’t even like to dance.” Redmayne was meeting with April to research his current role as Lili Elbe, the Dane who was one of the first known recipients of gender reassignment surgery. Elbe died after her body rejected the surgery in 1931. April would undergo a different, more advanced surgery three decades later.

Born George Jamieson in 1935, April asserts she was always aware that she was born in the wrong body. “I knew from the moment I could think. When you’re young and you’re different from everybody else you feel totally isolated. It’s not until you start to grow up and you realize there are other people like yourself that you start to feel comfortable. A lot of people commit suicide.”

April’s mother was a strict Roman Catholic. “I was terribly isolated. My whole family rejected me. We were six children. They wouldn’t let me play with them. My mother hated me, she used to hit me so much.” Her father was hardly home because of the war. When it ended, her mother threw him out. “I went to work the day after World War 2 finished. I was ten years old.” April worked in Liverpool’s St John’s Market, delivering groceries.

Life took an unexpected turn when she joined the merchant navy, aged 16, in an effort to “be like her father”. She travelled to Jamaica, Panama, and North America. Although she adored the freedom that being at sea offered, it only magnified how trapped she felt. April became so depressed that she attempted suicide, taking an overdose of pills. She was rushed to hospital, and eventually dishonorably discharged.

A chance meeting with a group of gay men back in Liverpool would introduce April to a different way of being. “One day I walked through the pier and saw all these boys who were totally outrageous. One had a pot of green eye shadow on each eye. I thought this was incredible! They took me under their wings. I fell in love with all of them: Little Gloria, Big Gloria, Pussy. I thought, ‘These are the most marvelous creatures in all the world. They’re strange like me, so I’m not the only freak.’ They didn’t give a damn about what anyone thought. I was totally fascinated.”

While her new friends gave April a sense of belonging, it further highlighted her isolation: one evening she arrived at the pier and saw them all “being their outrageous selves”, but then caught sight of a young straight couple kissing. As fond as she was of her gay friends, realization hit that April wasn’t really like them – she wanted to be that girl. This led to a second suicide attempt. “I thought I was never going to be able to have what she has, this great love. So, into the river I went. That was the first time I was in the newspaper. The headline read: ‘Youth saved by long hair’. Some young man dragged me up by the hair.”

When April told the specialist she wanted to be a woman, she was placed in a lunatic asylum. “You’re tied to a bed from your ankle to your thigh, up to your chest. The only thing that is free is your right arm. There are all these screaming people in the ward. They said they’d let me go if I became an outpatient and had electric treatment, which was very primitive in those days. It used to make your eyeballs bleed and give you headaches that you can’t imagine.” April was given male hormones, amongst other horrific treatments in an attempt to change her. The hospital eventually relented and told her to ‘go off and be a little homosexual’.

Hope arrived for April when she read in the paper about Christine Jorgensen, an American who had successfully had gender reassignment surgery. “All I ever thought about was that was my ambition.” Her journey to that goal led her to London, Cannes and, eventually, Paris. Here she found work presenting shows at the famous Le Carrousel de Paris nightclub, hosting the likes of Ginger Rogers and Salvador Dali.

One of the Carrousel’s most famous performers was Coccinelle. “She didn’t like me much. She’d been brought up by prostitutes. She was very common, but I adored her. She knew she was the star. She was incredibly sexy, with this lovely blonde hair and voice.” In 1958, Coccinelle returned from Casablanca having undergone the operation at the pioneering clinic of Dr Georges Burou. “She threw herself stark naked on the floor, opened her legs wide and there was a five star you know what! When I saw it I almost fell off the sofa.”

April set her sights on her own surgery. “I got to Casablanca and went to meet Dr Burou. He didn’t speak much English, he called me Mademoiselle Glamour Girl.” Did she suffer any last minute doubts before having such a major, relatively new procedure? “He showed me photographs that if you had any doubt in your mind, you’d run a mile. I wasn’t scared, I just knew I wouldn’t want to live if it wasn’t successful. There were side effects. I lost a great deal of hair, but it grew back. I was in a lot of pain.”

April returned to the UK and started a modeling career that came to an abrupt end when the Sunday People newspaper ran an exposé. “I never denied who I was. People would recognize me from the Carrousel. I never tried to deny it. All the photographers I worked for – Terence Donovan, Richard Dormer, David Bailey – they knew who I was, they didn’t mind. It was the product people. After 61 I never got a modeling job from that day to this. I had to take jobs in restaurants working as a waitress.”

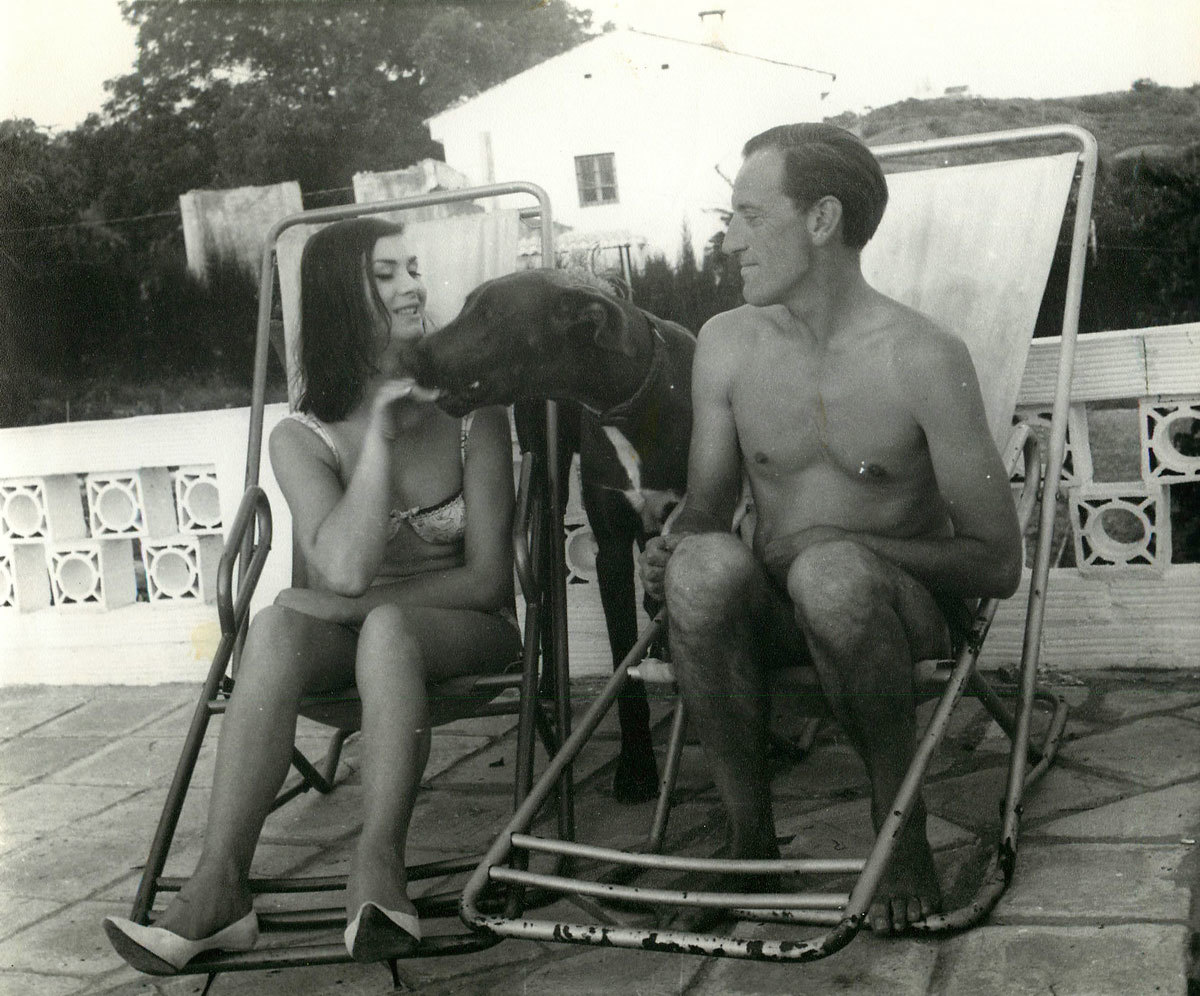

April remained defiant in the decades of ups and downs that followed, which included a high profile divorce from aristocrat Arthur Corbett. “I was always just making it by the skin of my teeth. I had no money at all. I always just managed, living right on the edge. The precipice was there, waiting for me to fall into.”

Years later, after writing to then prime minister Tony Blair, and with the passing of the Gender Recognition Act 2004, April was issued with a new birth certificate identifying her as female. Further recognition would be paid in 2012 with an MBE for services to transgender equality. “This has been a long time in coming,” Prince Charles said to her at Buckingham Palace. “Not really, your Royal Highness,” she responded. “I didn’t expect anything. I did what I had to do. I never asked anyone for any rewards.”

Credits

Text Cliff Joannou

Images courtesy of LGBT arts and social justice organisation Homotopia and the Museum of Liverpool.