It’s been said that fashion’s pendulum is swinging back towards fur – at full pelt. Vogue reported that a whopping 69 per cent of the world’s designers used it in their fall/winter collections in 2013. On the high street, the wearing of animal prints – think about all those silk-screens of leopard spots and zebra stripes, shoes and bags made of dyed cowhide, or a synthetic Bet Lynch-style fuzzy coat – remains a shortcut to cool, 70s rock chicks have been a style inspiration for well over a decade now. In today’s straitened times, rich and poor alike reach for glamorous signifiers: the wealthy engaging in pay-and-display as one way to reinforce their social position; while those with more dash than cash reach for animal skins already in the food chain, wrapping up warm in leathers, rabbit fur and sheepskin – or the occasional vintage mink picked up for a song in charity shops or flea markets. Added to the resurgence in creative, minimal-impact taxidermy by artists such as Polly Borland, there’s an aspect of today’s culture that wants to be where the wild things are. Faux or no, enthusiasm for styles recalling the luxurious, the primal and the retro has proven to be a full-fledged mainstream phenomenon. The look is so prevalent that Chessington World of Adventures, a theme park near London, banned its guests from wearing the prints during visits to the attraction because animals living in the safari park and zoo were so disturbed by the markings.

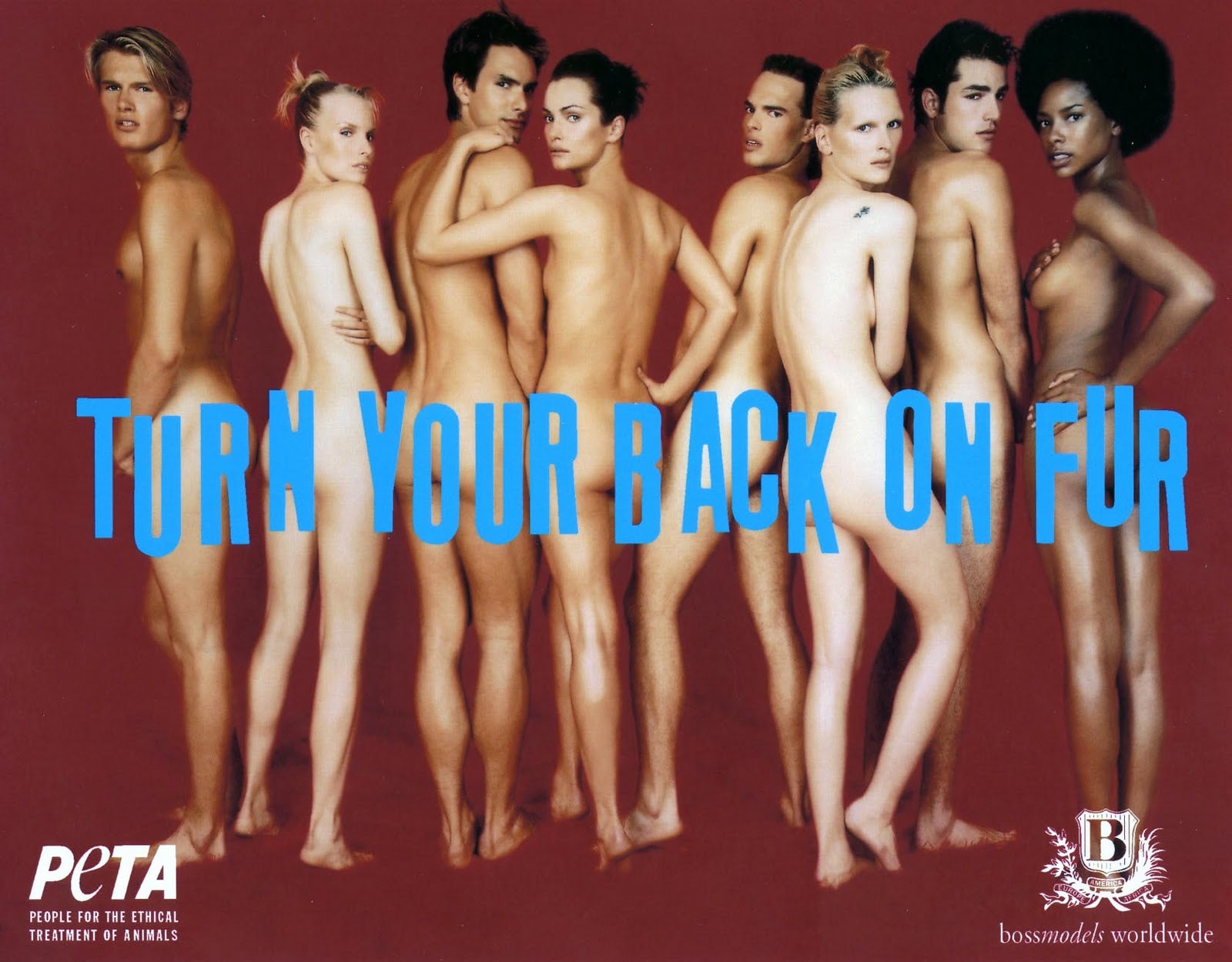

Maybe, like me, they were just a little bit cross. During the 80s and 90s, a loose alliance of anti-fur campaigners, animal rights activists and concerned consumers rallied to change public attitudes towards fur and animal cruelty. PETA picketed manufacturers, shops and the offices of fashion magazines years before models lined up to endorse their stance and to vow they’d sooner go naked than wear fur. In-herd diseases such as foot-and-mouth and BSE only served to reinforce the notion that we human beings were in an abusive, dysfunctional relationship with both domestic and wild animals, not to mention the environment. Many gave up meat and animal products, or righteously agreed with David Bailey’s unforgettable campaign for the UK anti-fur group Lynx: a lone model drags a blood-soaked mink coat along the catwalk, the caption ‘it take 40 dumb animals to make a fur coat, but only one to wear it’ seared onto a stark, white background.

Attitudes shifted, and broadly remain resistant to the fur trade: if taken at their word, as the RSPCA did in a recent poll, 95 per cent of British women say they’re unlikely to wear clothing and accessories made from any fur-bearing animals outside the food chain. Although many fashion magazines still accept adverts that show fur – i-D does not – most prohibit working with fur in an editorial capacity. Designers such as Stella McCartney have spearheaded efforts to manufacture better cruelty-free versions of our coats, shoes and handbags. Meanwhile, the Vegetarian Society claims at least three million British people call themselves vegetarians or vegans – that’s five per cent of the UK population. For those of us among the vast majority who do eat meat, wear leather and wool, use other animal by-products or benefit from the results of medicines tested on lab animals, many have applied the knowledge gained looking for cruelty-free fashion and beauty to fight for a clean environment, source our dinners from organic producers, and create further market pressure for kinder, safer food and energy.

If you’re looking for answers as to why the marketplace for fur has expanded after many wilderness years out of fashion, look no further than the upper classes of emerging economies such as China and Russia, clamoring to affirm their status with the literal trappings of wealth. Look also at fashion’s libertarians closer to home, from posh vermin in ermine who never put their coats into cold storage, to those venerable European labels whose core branding will always remain focussed on the myriad possibilities of fur and skin, to the emerging designers who subsidize their collections by accepting sponsorship from the fur trade, or to a recent wave of furriers mitigating impact on vulnerable species by turning to animals such as the coypu, a South American swamp-rat now breeding worldwide, whose lush coat turns up in fur showrooms re-branded as ‘nutria’. In the US, wild trapping of mink by individuals is on the up: Minnesota, where I’m from, issued more trappers’ permits for 2013 than at any point in the preceding 25 years. Prices for pelts are up 15 per cent in an otherwise challenging rural economy, in a state where initial white settlers were 17th century French trappers and traders criss-crossing its rivers and thousands of lakes in canoes laden with beaver, fox and mink.

Growing up, there was no escaping that past: my childhood home was built on a land parcel once part of a 1930s mink farm; my aunt lived four doors down, in a house rumored to be haunted by the ghost of the mink farmer himself. Our history lessons were filled with tales of les Voyageurs – those early French explorers – and after school, we played in the woods and marshes of our neighborhood under the watchful eyes of adults who were members of the Izaak Walton League and the Sierra Club. Some were old enough to recall the industrial-scale cruelty of the fur farms, and the hunters amongst them believed in giving something back to the land. During an era of rising public awareness about endangered species, wildlife protection and land conservation, we raised Canada goslings to adulthood and watched handlers from the state’s Department of Wildlife put tracking bands on their legs to record migration patterns. Our canoes were full of families paddling through state nature reserves, and freeways back into the Twin Cities groaned with fathers and sons returning from the first weekend of the carefully managed deer-hunting season with their eviscerated quarry lashed tight to roof-racks or resting in pieces in the back of pick-up trucks. Some of their families ate venison for months.

Today those of us who reach for fur when it’s cold outside need to have a word with ourselves about whether wild animals should have a place on our backs, and what we’re saying to others when we make that choice. Young designers need to weigh up their principles against obligations to commercial sponsors and create new collections accordingly. As for myself, near the back of my closet is a bespoke beaver-lined car coat my aunt commissioned in 1960, well before the advent of central heating, to wear to American football games played in the middle of endless sub-zero Minnesota winters. I could never throw it away. Unworn for decades, it wouldn’t look out of place on the set of Mad Men, but will never rest comfortably on me.

Credits

Text Susan Corrigan