At the very end of last year, one popstar pushed the Christmas crying season to new heights. Taylor Swift’s Gift Giving of 2014 was a six-minute video beginning with Swifto at home with her cats, wrapping gifts. Those handpicked gifts, none very expensive or elaborate, were then Fed-Exd to fans. The action cut to home movies of those fans opening their boxes. Taylor even delivered one by hand. As you’d expect there was a lot of crying, not least, I’d wager, from the clip’s 15m viewers. Well, I cried, anyway!

In the cold light of 2015, it’s easy to argue that the generosity in that video was simply the latest smart marketing move from an artist whose ascent to the pop apex has been signposted by a succession of smart marketing moves. Similarly, it would be easy to blame one’s emotional response on Christmas. Yet even now, that video resonates. And it resonates because almost nearly everyone has at one point dreamed of direct contact with their own personal Taylor Swift. At one point in our lives, we’ve all been fans.

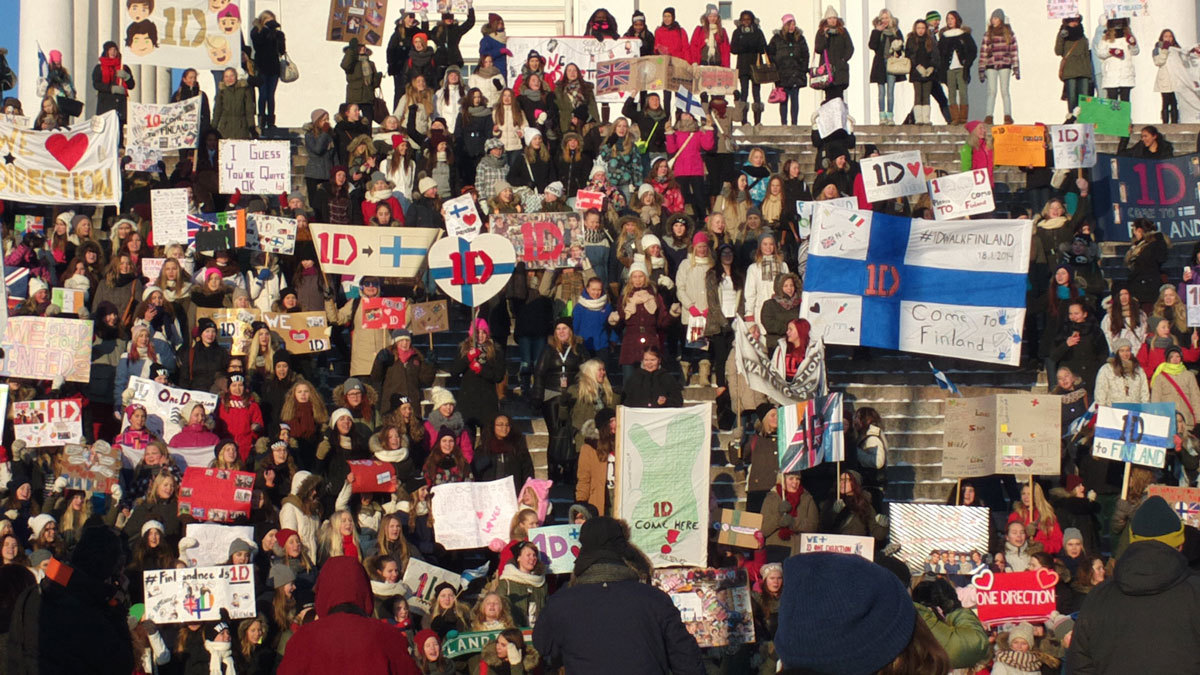

But fans are so often thought of as idiots. They’re dismissed because of their herd mentality, they’re laughed at because they don’t realize they’re the cog in a capitalist music machine. They’re ridiculed for their quivering meltdowns. More often than not, they’re derided as silly, pubescent little girls.

Whenever I see fans depicted in that way, I think of the grown men who have Twitter meltdowns when a new Apple operating system is announced, and I think of teenage football fans who, for some reason, aren’t laughed at when they get the same haircut as their favorite player, or wear their team’s colors, or book days off work around World Cup fixtures. Being a music fan isn’t that different from having a favorite team. It’s about being part of something, and just as football matches would be rather surreal if played in an empty stadium, so pop needs it fans. Without a devoted audience, the whole thing falls apart.

In his book 45, Bill Drummond, who was one half of iconic UK dance act The KLF, writes about his own experience as a fan. He recalls his obsession with the romance and mystery of avant-garde San Francisco rock act The Residents, whose well cultivated image involved things like eyeball masks, top hats and tuxedos. In a chapter called Now That’s What I Call Disillusionment 1, Drummond explains that when The Residents eventually came to the UK in the early 80s, he went to see them live. “I hadn’t prepared myself,” he admits, “for the fact that this glorious and epic band that stalked my imagination would simply be four blokes from America.” His abiding image, he adds, is that of some black curly hair sticking out from behind the singer’s eyeball mask. It must have been a bit like seeing those pap shots two years ago of Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter on a beach holiday: human after all, and not in the good way.

Fans are often dismissed as silly, pubescent, little girls. But why aren’t football fans laughed at when they get the same haircut as their favorite player, or book days off work around the World Cup? Being a music fan isn’t any different from having a favorite team. It’s about being part of something.

In Drummond’s next chapter, Now That’s What I Call Disillusionment 2, he writes about The KLF’s 1997 comeback show at London’s Barbican Centre. One of his former teenage superfans – by this point a journalist – was there covering the gig for Time Out. “As our hands shook, I detected something in the glint of his eye,” Drummond writes. “Disillusionment, as real and pure as disillusionment can get. Almost as powerful and strong as when I saw that bit of dark curly hair sticking out the back of that Resident’s eyeball mask.”

It’s a poignant vignette, which surely strikes a chord with anyone who’s come face to face with the fact that an idol – whether it’s a popstar, a footballer or even a parent – is just a human being. But my own reaction to that chapter was particularly powerful because that journalist and former superfan was, well, me. I’d fallen for The KLF when I was twelve: a year after they’d had a number one single as The Timelords (they’d decided a customized US cop car by the name of Ford Timelord would front that single) and two years before they became, briefly, the planet’s biggest-selling singles band. To be honest, I was a total pain in the arse. I’d phone their publicist, their radio plugger, even the band’s own office, once a week. When the band appeared in Smash Hits, I considered it perfectly acceptable to phone the journalist and ask him for the interview tape. God only knows how much more intense I’d have been if the internet had been around…

Strangely, The KLF and their team not only tolerated all this but – while almost certainly rolling their eyes when I phoned up with some inane question about the catalogue number of a German import – seemed to welcome me. After they cancelled a (proper) live show I’d bought tickets to, they invited me to see them perform on Top Of The Pops and hang out in their dressing room. I was sent a cassette of a shelved album that, over twenty years later, remains unreleased. On my 13th birthday, I experienced my own Taylor Swift moment when the band sent me an insanely generous package of signed memorabilia, including one of Ford Timelord‘s old tax discs. I later found out their initial plan had been to drive their car down to East Grinstead, and dump it outside my house. My reverie would probably have continued had I not been jolted out of it by the band’s sudden split. I was 15 and the timing couldn’t have been better because, to be quite frank, if they’d kept going I might never have lost my virginity.

A few months after their split I put together a fanzine about the band, found closure and got into other artists and styles of music, but looking back on my time as a teenage superfan I find there’s something about that blinkered belief in one true pop god that’s both comforting and exciting. Fast forward a couple of decades and I encounter superfans as part of my job. These days, social media holds up a mirror to fandom with results that are frequently grisly. At least with Candyman you needed to say his name three times before he turned up; tweet about Christina Aguilera unfavorably, just the once, and the carnage is both immediate and merciless.

I later found out The KLF’s initial plan had been to drive their car down to East Grinstead, and dump it outside my house. My reverie would probably have continued had I not been jolted out of it by the band’s sudden split.

In the higher echelons of modern pop fandom, devotion to A-listers resembles a bloodsport. One act ‘slays’, so another cannot: you stand for Beyoncé so you can’t like Katy Perry, you stand for Katy Perry so Gaga’s a flop, and so on. It’s not enough to love your favorite popstar: your love only means anything in the context of hatred for everything else. Conversely, in the lower levels, fans are almost comically promiscuous, if not mercenary. When new boybands come out potential fans hedge their bets between any number of hopefuls, ready to pounce when one succeeds – and ditch the rest. As Union J might tell you, 1.5m fans aren’t very useful when 1.3m of them prefer One Direction.

Of course, a truly devoted fanbase can be as much a curse as it is a gift. Consider last year’s leak of Madonna’s new album, many months ahead of release or even completion. At the time, Madonna asked fans not to download the songs – her argument being that a true fan would respect her art. My own reaction was rather different: what sort of fan wouldn’t want to hear their favorite artist’s new work? But there was a more pertinent issue, which arose from the praise with which Madonna’s hardcore fanbase swathed a set of leaks whose quality was, shall we say, variable.

In fact – and this is important – let’s not be coy, some of the songs that leaked before Christmas were among the worst Madonna has ever recorded. Plenty were great, many were promising, but a large selection were beyond woeful. Yet in the social media echo chamber, all Madonna heard was encouragement. Fans who pretend everything’s great are the architects of their idol’s ultimate demise. A fan might feel that they need to praise every move, but surely a true fan knows when they’re being an enabler. And that – it doesn’t take a Jessie Ware superfan to tell you – is called tough love.

Seeing Madonna losing control of her music, and feeling it necessary to ask fans not to listen to it, was a stark reminder of pop fandom’s great power shift. The fan/artist relationship has always been about give and take from both sides, but with money falling out of record sales and coming increasingly from sponsorship, that power’s now shifted.

Seven years ago, Kevin Kelly’s influential blog post 1,000 True Fans argued that concentrating on a small number of true fans could be the most effective way of sustaining a long-term career. This is true for some artists, but in 2015, in the social and endorsement age, fans are used by artists as bargaining chips. The more YouTube views you can deliver, the more you can charge more for shoddy product placement in your new video. The more Twitter followers you have, the more you can charge for a sponsored tweet.

Fans may not realize it when they beg their idols for Twitter follows just as they begged for autographs in the pre-selfie age, but they increasingly hold all the cards. I’ve met plenty of pop bands at the very start of their careers. Off the record they’ll talk about their hopes and aspirations. They’ll wonder who, if anyone, will like them. They’ll talk about signing autographs being exciting and special. As time wears on, off the record chats take a less pleasant tone. Often, within a matter of weeks, the popstars are hiding in dressing rooms, running from venues to waiting cars, pretending to be on phone calls, all to avoid fans. Fans are a hassle and an inconvenience. Artists would never admit it in public, but they resent fans who won’t let them change or grow up, in the same way they’d hate their domineering boss if they’d got an office job. And pop artists, just like a lot of artists on the more credible fringes of music, know that one day the majority of those fans will simply drift away.

Seeing Madonna losing control of her music, and feeling it necessary to ask fans not to listen to it, was a stark reminder of pop fandom’s great power shift.

There’s a great song called 18 on One Direction’s album in which the band sing about having loved their listener “since we were 18”. While the band’s debut single was all about the first flush of romance that song is about growing up, and the passing of time. Sometimes when I watch a band perform to 15,000 screaming fans in an arena, it seems impossible to comprehend that within five years they’ll have split. Two members will have been dropped following underwhelming solo careers. One might end up in rehab. Another will be desperately trying to flog tickets to his awful rock band’s next 200-capacity gig. But it happens, and it happens all the time. Fans move on. After a while, those fans will forget all about that band.

But then twenty years later, they might find something in a box – an old band T-shirt, or a school homework diary with a logo scrawled across it. Maybe they’ll just chance upon an old selfie they took at a gig. And maybe, at first, it’ll seem silly. But then they’ll be hit by the full force of their long-forgotten teenage obsession. It will feel, strangely, as if Christmas has come early. And they’ll feel the sudden, unexpected urge to cry.

We may not all faint at the sight of Justin Bieber. We may not attempt to trend Katy Perry’s name on Twitter every time she tweets a picture of a balloon, and we may not bid on eBay for a piece of Harry Styles’ dried up sick, but one thing is certain: you should never trust anyone who’s never had a favorite popstar.

Credits

Photography Hugovk