“Technology shrinks the world” is the type of truism that you might commonly stumble across but which manifestly isn’t true. Just ask Holly Childs, who has spent the last three months living in London, but only got here by way of 30 hours flying from her native Melbourne, in Australia. “Hard 2 know what someone smells like from other side of PLANET,” she responds, pithily, when asked what attracted her to spending time in London.

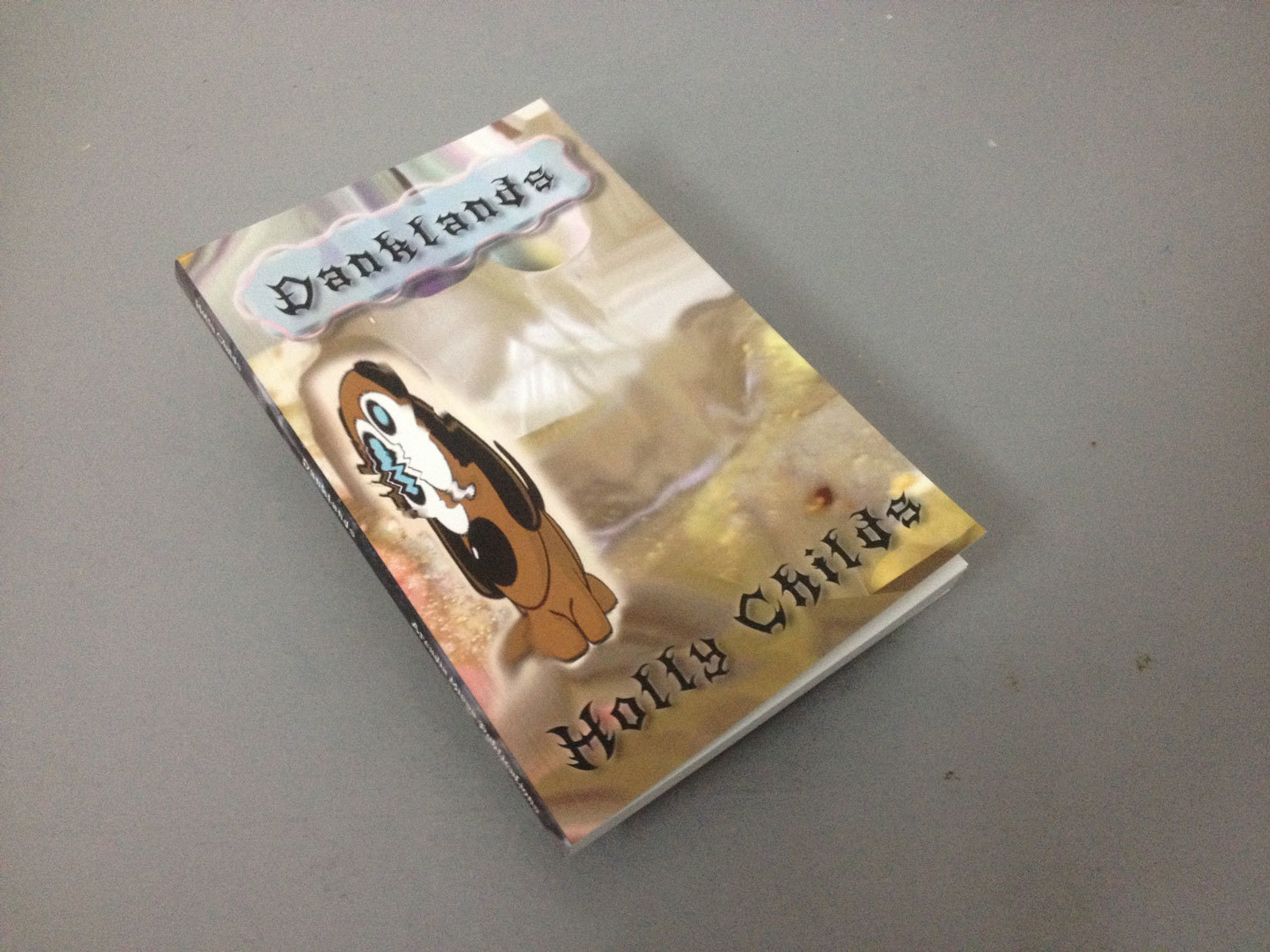

She’s here to launch her latest book, Danklands, published by Arcadia Missa. It’s one of the most literally (and literarily) breath-taking novels to be published this year. Danklands, which follows her debut novella No Limit, published early this year by Hologram, is set in Melbourne Docklands, a newly developed area next to Melbourne’s Central Business District that, Holly says “critics and city planners both love to hate.” A former swamp, in the 19th century the area became a shipping dock for the swiftly growing city, however by the 90s the area had been virtually abandoned, becoming a hotspot for the city’s underground rave scene. Today it is a minefield of high-rise buildings and ready-made landmarks.

Although ‘located’ here in the loosest of ways – Danklands has a very polyamorous relationship with old school writing conventions such as linear narrative and fixed geography – the history of the Docklands area gives important clues to the shape and language of the book. If the Docklands is an urban business district that has been dredged out of the quiet solitude of a swampland, through industry and rave, then Danklands is an attempt to dredge back the swampland in the middle of the bland, homogenous district, via its own “5-HTP magnesium comedown afterglow girl” – fuelled language, which reads like a stream-of-consciousness social media feed that draws as much on globalised slang as it does literary history. Its text twinkles between the tidy, presentable grammar that you’re supposed to write with, and complete disintegration of punctuation and spelling, as Childs allows the affect of her words to rise from way below how they’re supposed to look, and instead writes like, well, she’s texting you.

Clearly taking cues from the visual logic of a Ryan Trecartin and Lizzie Fitch movie – who are both thanked in the acknowledgments at the back – Danklands nonetheless accepts the real mania of their output as ground zero language for manic real talk about issues like sex, globalisation, homogenisation and love.

Meeting Childs immediately affirms the realness and sincerity of her voice and her writing. With long, deep yellow hair (“since like 10 days ago people have been saying it looks green, I wonder what shifted”) and a 3M Scotchlite puffa jacket she looks exactly like the kind of character she might write about – the kind of person who at first you think is too colourful or present to be true, but who is here and totally bossing you.

As she says about the idea of fiction in her writing, “I guess any act of creation switches from fiction to reality in the process of making/production. A make-up tutorial is fiction until it is recorded and uploaded.” This spills over into her lived reality, as she dredges ideas from the novel and people and places from back home in Melbourne into our conversation. In some sense our experience with smartphones and social media enforces this kind of roaming, as memories in the form of images, posts and videos are constantly being pushed to the top of our feed. Childs hijacks this as a way to turn fictions into realities, breaking down distinctions between creative output and objective experience as she goes.

It is this mentality that allows Childs to be experimental in her language (“altern8 real80 ov werld trade centre falling inward in2 each othr faling togetjrt in spiral form dubel helix due 2 each othrs vacuum (frm fire and falling, internal fire whirls) … spiral ambient impact” – Danklands moves constantly from novel to poem and back again, but it’s also this mentality that allows her to view the book itself as an experimental form of technology. As the poet and writer Astrid Lorange observes in her fantastic preface, “Danklands is an index and its object is a book of the same name… Childs imagines both form and mode (book and poetry) in their extended capacities: the book as a technology, open field, social context, meditation mp3; poetry as a mode of emphasising and studying the emergence of language.”

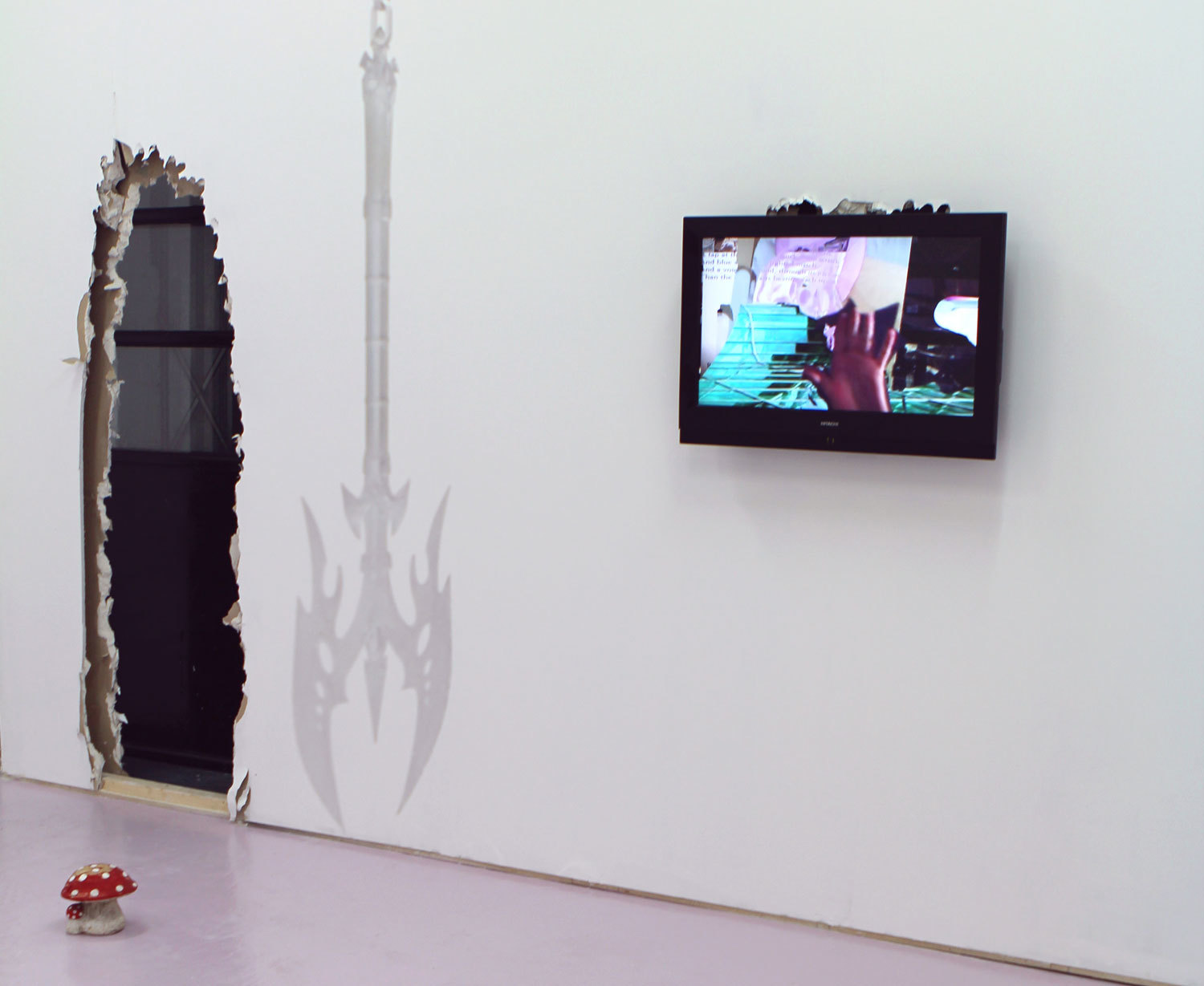

Taking this to heart, Childs has also curated the exhibition Quake II, currently on view at Arcadia Missa, starring Sydney- and Melbourne-based artists Marian Tubbs and André Piguet. It isn’t intended to illustrate the book (although Tubbs provided its cover art, and the Andre in the book shares certain characteristics with Piguet) but instead attempts to expand the platform of the written word to promote similar ideas through different forms, making the point that a hanging sculpture of an axe (as in the exhibition) can share the same aesthetic as a book, not least when people are so filtered through the same scenes and social media. The exhibition and the book are allowed to cross-contextualise each other; there is no necessity for them to be individual things. As the press release for Quake II states, suggestively, “In fact, much of the book may be objects in the space.”

By this logic, the book collapses into the exhibition, and vice versa. But this also crashes into ‘real life,’ across 11 time zones on the other side of the world – albeit in a city with the same insane observation wheel spinning round and round. I’m wondering why and how this could be, whilst Childs shouts out “oh cool this is getting likes now, I thought it was broken” about a photo she’d uploaded. I can’t work out whether she’s addressing her phone or the people around her, or indeed which one is fiction and which one reality.

Credits

Text Harry Burke

Images courtesy Arcadia Missa and Marian Tubbs