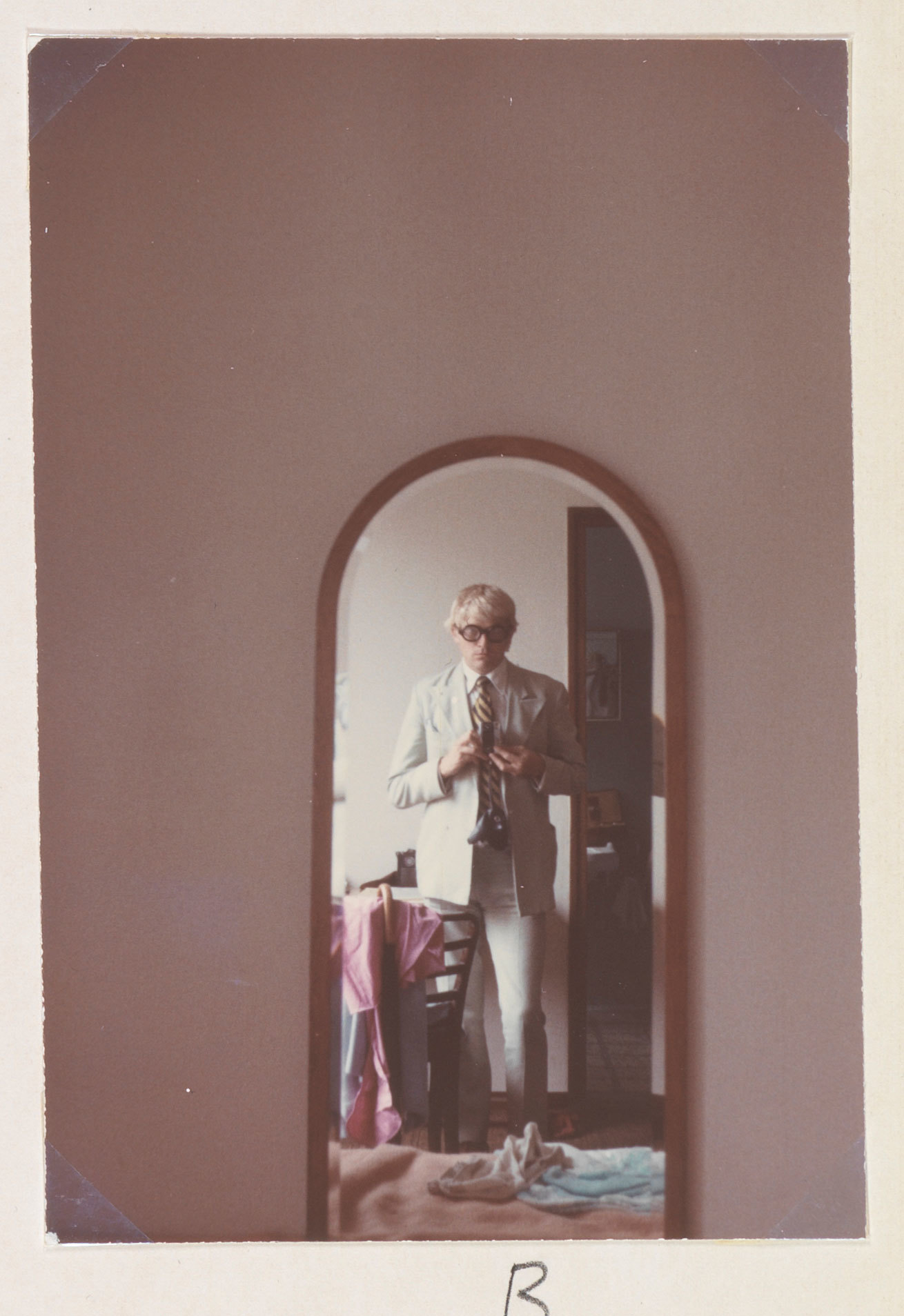

Throughout the documentary though there is a sense that Hockney battled through all his demons and misfortunes to become single minded in his pursuit of artistic beauty. The soundtrack, by acclaimed composer John Harle, only adds to the sense of playful complexity with sweeping strings and his trademark mournful saxophone replacing the standard voiceover. With the director being a personal friend of Hockney you get a sense of intimacy that is usually lost in most retrospectives of an artist’s work. i-D talked to the director Randall Wright about filming with Hockney, being his friend what it was like to capture the late, great Freud in action.

What made you want to make a film about David Hockney?

I wanted to make a film about David for a long time, he’s an extraordinary character. He’s a great mix of the outrageous, mischievous and the rebellious, whilst at the same time he’s very sweet and accommodating.

How did the two of you meet?

I first met him nearly 15-years-ago at the National Gallery, he was making a painting based on an Ingres painting. Ingres’ techniques strongly resembled photography and David was curious about how he did them. We met then and bonded over a mutual love of art and painting.

What do you think makes him so interesting as an artist?

There’s only one other artist, Picasso, who mastered so many different media. He’s a great person to document.

Did the fact that you are friends affect the project?

We’re friends but it’s very clear who’s in charge, and it’s not me! There wasn’t really a problem with the dynamic in filming though. David allowed me to film interviews with him and I did five in the end, he left me to get on with it though. He didn’t ask me what the film was going to be about or who I was going to interview, he just broadly approved of it.

Has he seen it?

He’s watched it and didn’t ask me change a frame, I think it’s a very intimate film overall.

You avoided a warts and all portrayal…

Well there’s not an ugly side to David Hockney, that’s what makes him special. He’s very literal, a lot of art now is about irony, it’s skeptical and often cynical or sarcastic. David would regard sarcasm as the lowest form of wit. Art should be transparent to an artist’s emotions. When David paints a picture he’s telling you what he thinks and feels, it may involve quite a lot of detachment, but it still carries a lot of emotion though. The idea of a warts and all film to me suggests that there is a deception going on. He is tough and uncompromising but there isn’t another side to him, he’s had a great deal of suffering with his love life going wrong, or his fear of nuclear war coupled with how all his friends were dying of AIDS. He’s very loyal to his friends, I have shown the real Hockney, so what you see is more or less the complete person.

You could have gone down a more conventional, biographical route though.

Yeah, there’s always the strict timeline story, getting in as many talking heads as possible. You could get in people who love and loathe Hockney, but that just makes art feel like a sport.

The music really sets the tone of the film.

John Harle, the composer, is amazing. Before I even start shooting I talk to a composer and we think about the tone of the film. The music is crucial as there’s no commentary. I wanted quite playful and spontaneous music to match David’s style.

Hockney uses iPads and digital cameras for his work, but does he embrace other parts of pop culture?

He probably won’t like me saying this but he watches a lot of populist TV from Mad Men, which is really his era, to Downton Abbey,which he thought was going to be awful but ended up loving.

In the film he’s described as unintentionally rude, how does he maintain friendships?

The problem is, he’s always right! He gives blunt but sometimes needed advice. Though when he’s focussed on a painting. that’s all that matters to him.

I also wanted to ask you about your documentary on Lucian Freud, how did you get a chance to film such an intimate man?

It happened by luck because there was another film being made and the filmakers had somehow got fired which is quite common with Lucian Freud. He’s very binary, either you’re in or you’re out. I’d first met Lucian when I was with Hockney, Hockney absolutely adored Lucian Freud and would see him whenever he came to London. As soon as Lucian appeared, I scarpered, with the sense that I shouldn’t intrude. I told him this ten years later and he remembered me! He then offered me a bit of nougat, which he ate all the time because of all the energy he used whilst painting, because he was nearly ninety then.

What did your discussions involve?

He asked me a few questions and then said “I’ll give you all the rights to the painting so just go off and make the film.”It was an amazing opportunity. Then as soon as I started making it he died! I’d already got his assistant, David Dawson, to film Lucian painting and it turned out that was the last day that he ever spent painted.

How do they differ?

Hockey paints his friends, and they’re quite balanced. Lucian Freud is a very unusual, attractive to women and some of them got damaged in the process, but I don’t think he ever lied to them or pretended he was something he wasn’t. Lucian thought David’s work was different to his own, but they liked each other. There’s a real mutual respect but in the end they’re all figuring out how to make the perfect picture.

Credits

Text Dan Wilkinson