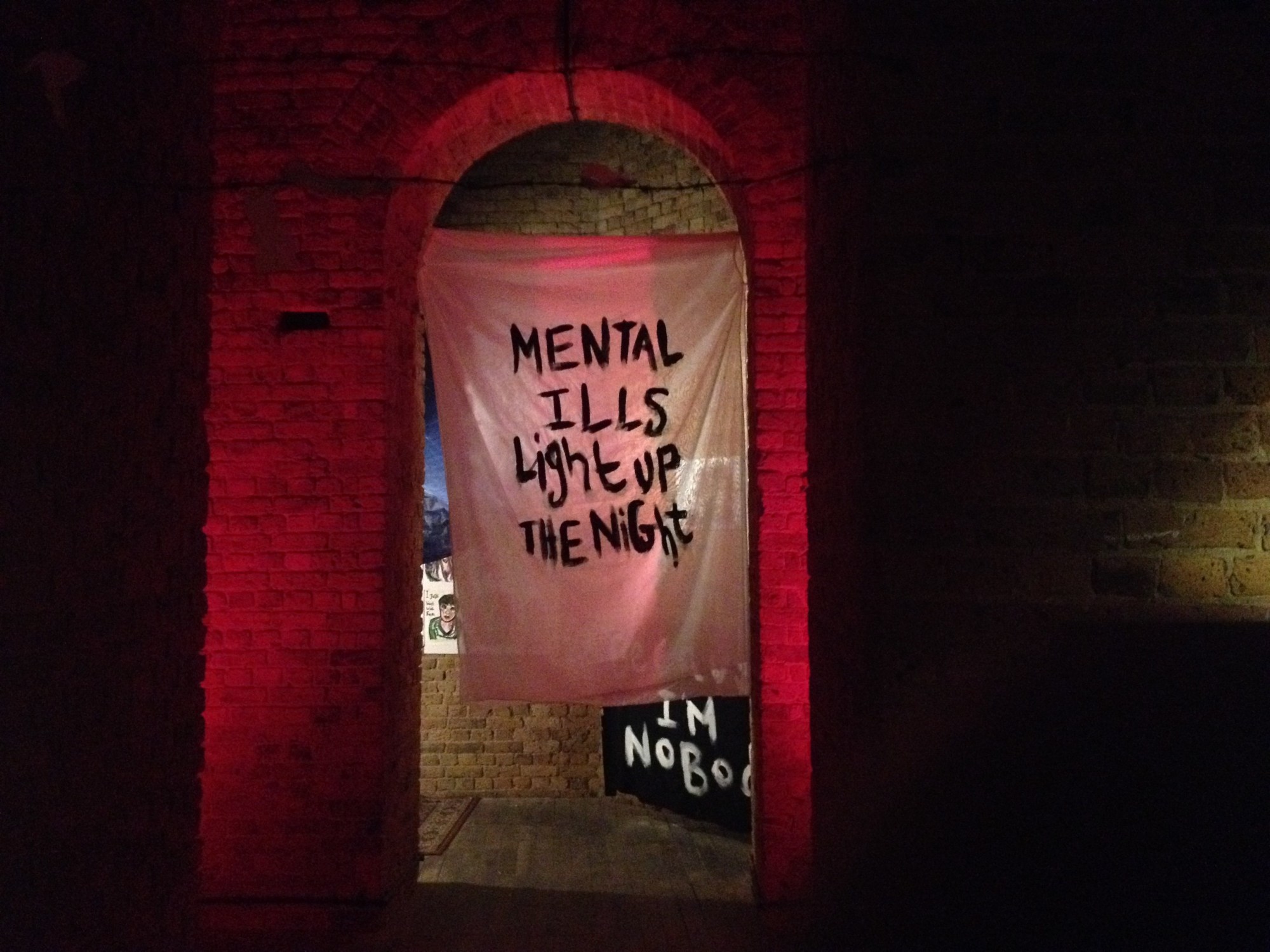

Night On My Mind takes place at Waterloo’s Gallery 223, a space seemingly built for a show dedicated to the dark nights of street life. Beyond a looming entrance – the film’s screening room – are odd-sized brick wall rooms bearing the art, and motifs such as a barbed wire fence and red lighting. All the while, the soundtrack is the heavy rattle of trains overhead- not a CD, but real.

We met the creators of the exhibition – Harry Conway, photographer, who tabloid readers may know as Zerx, a prolific graffiti writer who served three months in Wormwood Scrubs; his brother and outsider artist Oliver Conway; and filmmaker Molly Manning-Walker (photographer Ivan Bliminse was absent at the time). We gathered in Oliver’s section of the exhibition, a mockup of a prison cell replete with an armchair, burning incense and walls covered in paintings, to discuss their work, why people graffiti and the state of contemporary London.

When did the idea for Night On My Mind come about?

Oliver Conway: I used to send a lot of letters to my brother when he was in prison and I said we should definitely do something when he gets out, something to focus on while he was in there. We had the idea for the exhibition since then, but where it all came from was a project my brother had at London College of Communications, where he was looking to put on a show. I had access to this space so I thought it’d be the perfect venue to have an exhibition on graffiti somewhere we could do something more interesting than just putting throw-ups on a canvas. Molly made the documentary beforehand and Ivan studies alongside Harry at LCC.

How do you avoid the clichés that come about with putting graffiti in a more formal setting?

Harry Conway: Ultimately, we’re not in the White Cube looking to sell our work, but to get a message out there: end custodial sentences for writers. That is the main aim of the project, if we can raise awareness. Even today we’ve had people pop in who didn’t even know graffiti is illegal, let alone that you can go to prison for it. We had such a focus on that that for me, I didn’t have any apprehensions.

What would you say is the mood of contemporary London graffiti?

Harry: Graffiti in London’s always had this aggression; it’s always been aggy. You can go on a street art tour in Shoreditch, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg, if you want to get into real graffiti, it’s pretty damn rough.

Oliver: I think it’s pretty insane that there are about 35 full-time writers who’re out every night and that’s a very small community, everyone knows each other… that influences the aggression. People step on each other’s toes.

Do you regard graffiti culture as responding to larger societal problems?

Molly Manning-Walker: There’s anger against the system, as well as anger towards other writers. As my description board says it costs £10 to get across London now, people are pissed off and not happy with the way London’s going. It’s becoming a bleak place, so people will go out at night and spray all over the walls.

Harry: It’s also an anger release. I don’t go out and drink booze on Friday night, get smashed in a pub. I go out and deface – if you want to call it that – walls in London, that’s my release. Instead of going for a walk in the forest, which I might do every now and then but not every week, I used to take a few cans and do my thing, not hurting anybody.

Oliver: As I see it, all of London’s public space is being taken away; there aren’t youth clubs or places you can play ball. Everything’s becoming something you have to pay for and graffiti’s the ultimate ‘fuck you’ to that. With me, I had a problem with the violence of graffiti, I’m not a violent person and I thought that it was too aggressive. I’d never write graffiti, as it doesn’t provide that release for me, I can do it in my own work.

What do you view as the result of imprisoning graffiti writers?

Harry: You’re taking people who are trying to live on the outskirts of society, trying to avoid people, going out late into the night, into a prison where they’re confined and next to everyone. When they’re put into that situation, it doesn’t work… being in cells with murderers, rapists and gang-leaders, thinking ‘I’ll have to stab someone to death if they try it with me’, that’s bullshit. That should not be happening. One writer is very publicly known as having died in prison, that’s fucking bullshit. I can never stress this point enough: when you put graffiti writers in prison, you’re just escalating it. What’re they learning in prison? They’re learning other crimes.

Molly: And is the paint still not up on the wall? You put people away, the paint’s still up on the wall and we’re paying for them to be in prison, so what are we solving by that? We’re just creating a bigger problem.

Harry: I’ve come out and most of my tags are still there. Of course, graffiti gets buffed but I’ve got so many tags still around London. I don’t know what’s changed; the system is completely broken in that respect. I don’t say that as some generalised point, in terms of graffiti, the system does not work… Until you get something like legal walls, which are largely being shut around London, where’s it going to spill out to?

So do you get the same feeling from photography that graffiti gave you?

Harry: No, it’s like chasing a buzz, photography’s amazing but different. This time I can display what I’ve done, put my name on it instead of my alter ego. People can come up and say ‘I like that’ instead of ‘oh, seen Zerx about?’

How does it feel to watch a film that reflects your own life?

Oliver: My first reaction when I saw the film was that it’s too one-sided, only showing one perspective. But Molly tried to get in touch with people from Transport For London, Boris Johnson…

Harry: British Transport Police, Met Police, councils…

Oliver: But when I watched the film, something I said struck me; it was that my brother was put in prison for page seven of the Evening Standard. The side shown on everything else – the TV, papers – is anti-graffiti, ‘fucking vandals’. There were anonymous commentators on the Evening Standard website – blatantly the BTP – posting ‘hang him’. When you have an establishment view like that, I’m sorry but 15 minutes of the other side is pretty fair.

Any worries about the exhibition ahead?

Oliver: A lot of my work is on tissue paper and will disintegrate after a number of years. I like the idea it gets fucked. There’s a good chance someone’s going to come in and tag all over it. It’s uncovered, unframed, there’s nothing to stop someone from damaging the fuck out of it. Ultimately that’ll just become part of the work and I’ll leave it up, I’m not going to close the exhibition because someone wrote their name on my work. It’d be pretty hypocritical.

Harry: We’re holding this event, the space might get tagged and we’re stressing about it all week, but so what? We’re going to paint over it tomorrow, everything will be fine and nobody’s going to die.

Night On My Mind runs until 28th November.

Credits

Text And Photography Fin Murphy