Jack Pierson makes being an artist sound like the easiest thing in the world. Uncomplicated if pursued with a few simple rules, a clear mind and a light touch. At any given time, you make the work you want to make — in his case, portrait photography, text assemblages, and found-object installations — using whatever (or whoever) catches your eye at that particular moment. Then you present the results however you see fit, with bonus points if it subverts the form’s conventions or the art world’s rigid categories. Your place in the art ecosystem — and what constitutes your own ‘style’ and legacy — are questions best left for critics and curators. In the meantime, the next project beckons.

I’m speaking with the Massachusetts-born artist about the release of a new edition of The Hungry Years, his 2017 photobook of images from his youth during the 1980s, which have come to be known for their warmth and easy sociality. Fallen disco balls, sprawling lovers and drive-thru meals against the backdrop of America’s AIDS epidemic. “It’s the first decade of my artistic life,” Jack tells me from New York City, where he’s working on a major show for 2023.

The distinction between life and art is an important one. The Hungry Years photographs were the first he ever showed in a gallery, but it was “collecting them together and printing them in this way that made them into art,” he explains. Until that point, they were just snapshots of his own experience: travelling, partying with friends, queer love.

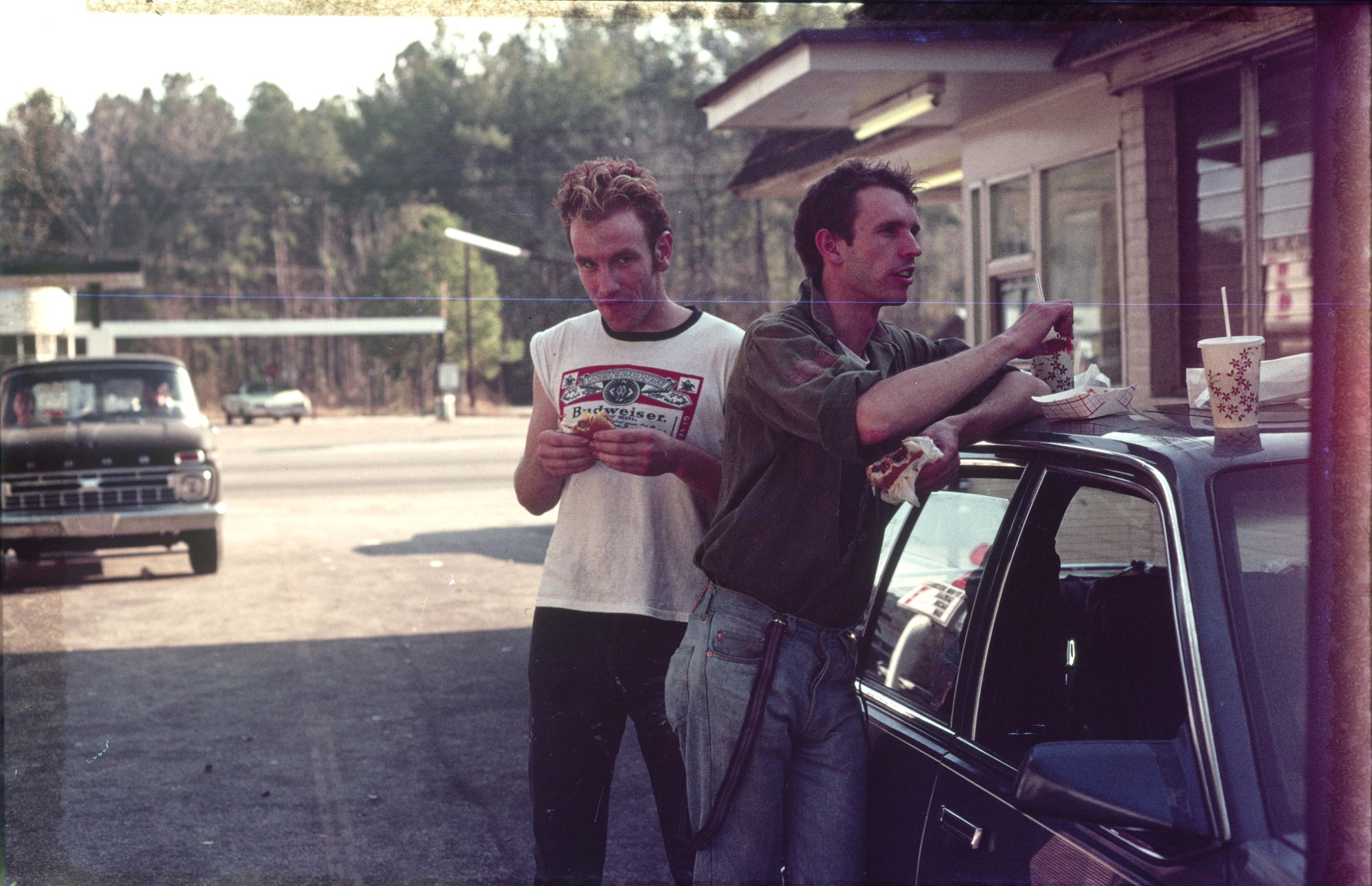

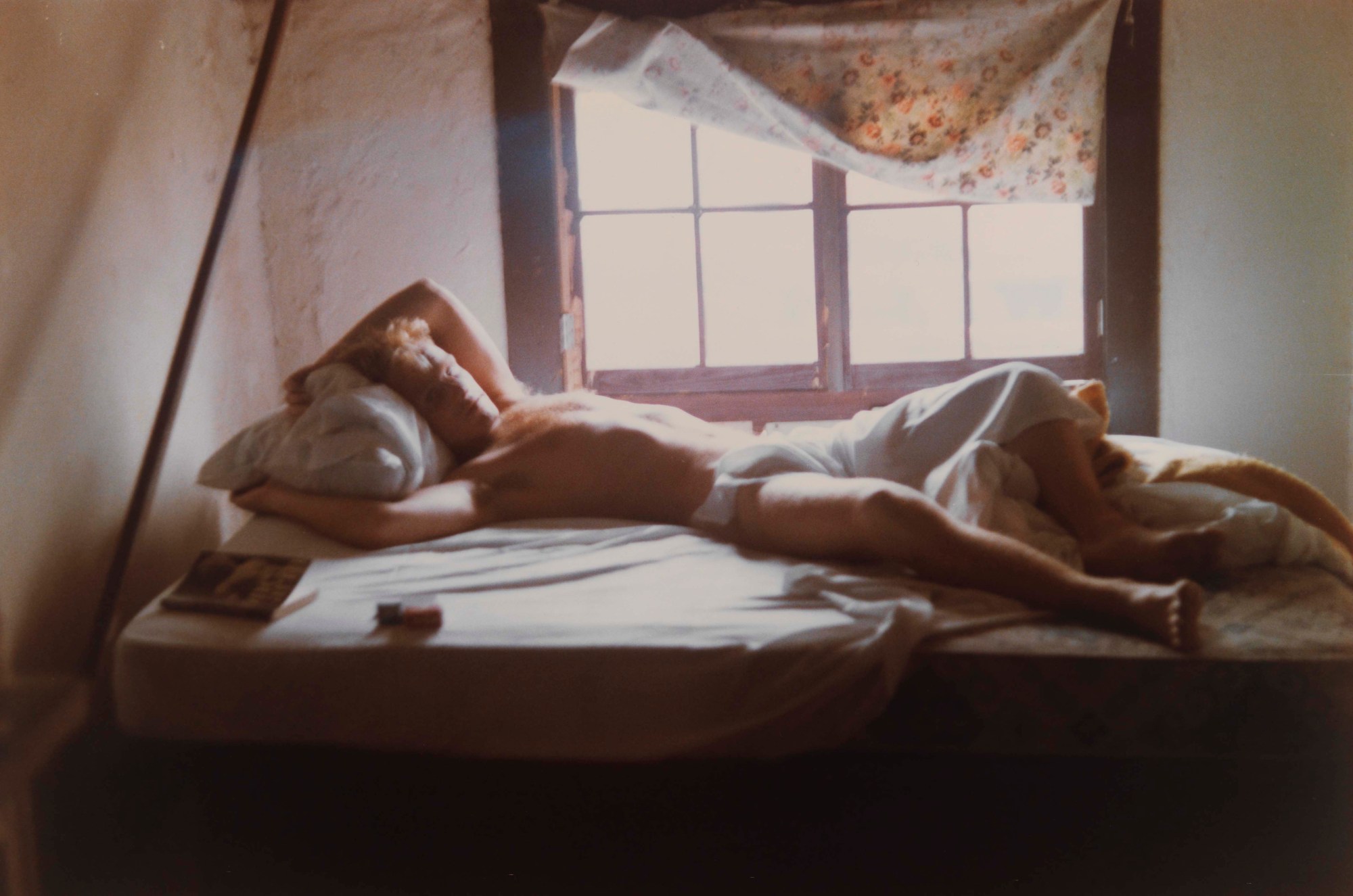

The photographs appear somewhere between diary and fiction, subjects character-like in stature but at ease in their quotidian lives. Men lean on parked cars or lie on floating inflatables in pools. When captured in more intimate settings, they pose confidently (often nude) while women feel more tentatively observed. The expansive roadsides and dusty horizons give a sense of motion between the scenes and yet feel detached, as if forever untouched by the youngsters in adjacent plates.

“These photographs are pictures you would see in someone’s biography,” Jack says. “‘This is where they lived…these are the characters.’ Almost non-photographs.” They take on an anonymous quality as the years pass, and as the artist’s friendship circle and perspectives have changed. “At the time, they were received almost as though they were found,” Jack says. “Snapshots I had curated.”

Jack stopped taking pictures of his own life around 1995, after which a career in commercial and fashion photography followed. A more choreographed style fed into his fine-art practice. His 2003 Self Portraits series featured 15 men of different ages in various states of undress. The highly saturated photos of fragile beauty brought him great acclaim — and ushered in a tendency for editors and directors to request shoots in the “Jack Pierson style”. He laughs at the memory. “I like the style of no style,” he says. He mentions anonymity again, favouring making images that could appear on bus shelters or billboards, a nod to his Boston School roots alongside Nan Goldin and Mark Morrisroe.

Less and more, a major solo exhibition at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, last autumn displayed Jack’s text collages alongside installations recreating domestic rooms, gentle watercolour paintings, wrapping paper tessellations, and works on paper. The most recognisable of the Self Portraits photographs was hung prominently, but on closer inspection is an image of an image: the New York Times caption from its publication remains below the subject’s torso, his skin a little grainier in this front-page cutout. Mythology of the Self, the work is called, a nod to the wry self-fashioning that constitutes Jack’s process.

These tricks are delivered with knowing humour (another work is a collage of newspaper clippings from stories about Jack’s own art), but they also speak to his concern with the nature of the photographic medium. Photography (“capital P”) stands separate from photography in the moment of creation, the affective instinct. Jack’s snapshot style keeps him rooted in the second category, while the first remains a strange zone into which he can enter at will, just by modifying the works’ contexts or display conditions.

“In The Hungry Years, there are a couple of images that, if you printed them right, would look like New Color Photography that’s important, or by a fine artist,” Jack explains, seeming to exempt himself from the canon. Creating the book was an experiment in blurring this line, in transposing artefacts of experience into art.

“By not full-bleeding them, by not making the layout super pretty or travelogue-ish, I’m asking: ‘Do these hold up as 35mm pictures like Stephen Shore’s?’” he says. “And I think they do, but the joke was to present them really formally.” (A quote from Stephen printed on the book’s back cover contests Jack’s modesty: “Authenticity is what Jack Pierson’s pictures convey. They have the feel of raw experience… Jack disrespects the merely good for the sake of the expressionistically real.”)

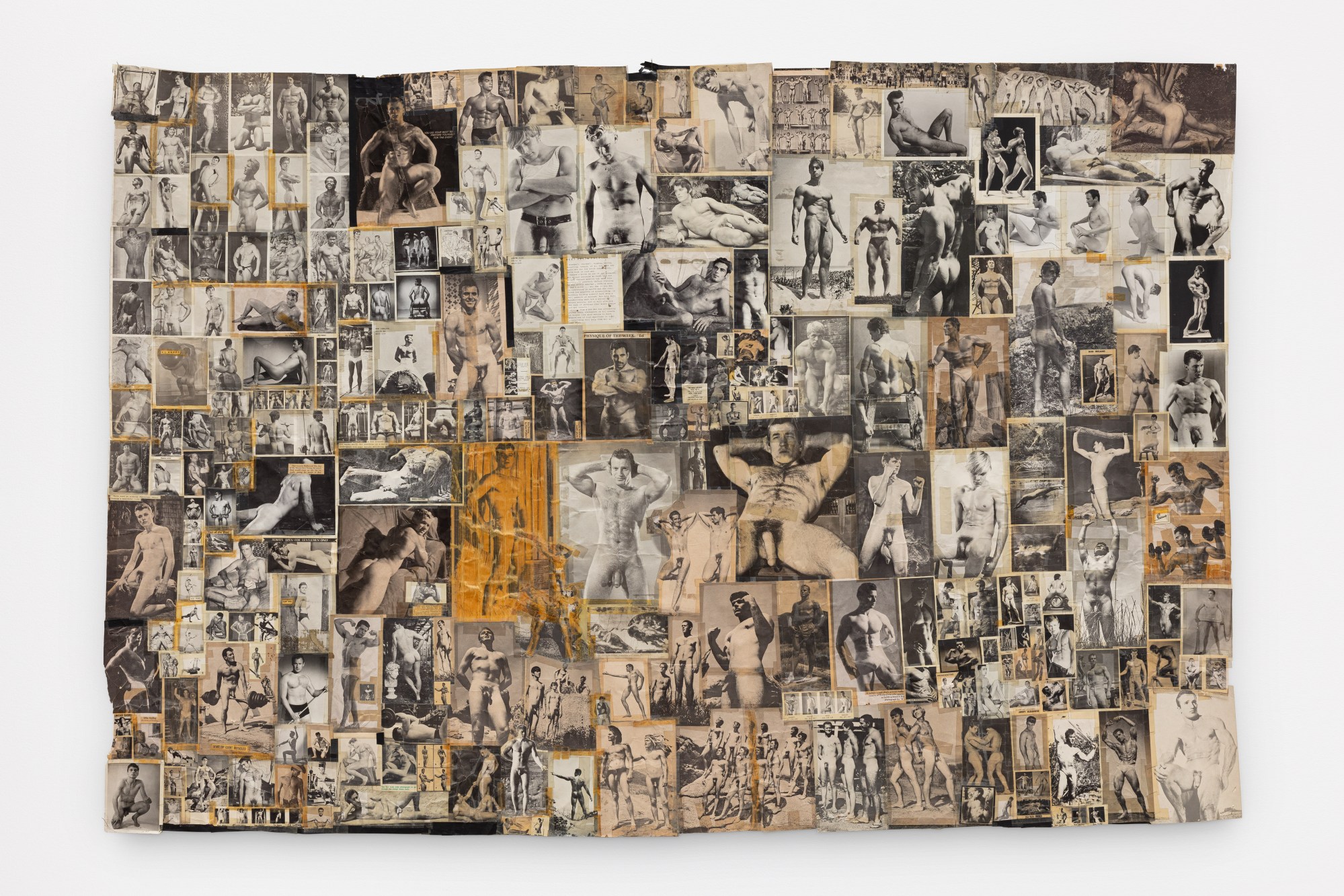

Humour is the key factor in the text works, too, a mixture of linguistic play and social observation rendered in carefree assemblage. The pandemic lockdowns allowed him to sort through years’ worth of clippings and ephemera in his Queens studio. “I thought: ‘Who the fuck blows up their newspaper clippings about themselves?’ Okay, I’ll be that person.”

He also created new assemblages featuring cloth, pins and cardboard grocery boxes. The repeated slogans may tempt Pop Art comparisons, but the works feel too considered for that; they are soothing and muted, especially Blue, which features an Adidas shoebox brought into dialogue with a pastel blue slab beneath it. Simplicity is the answer to most questions posed at his work, especially regarding choice of materials. “Once you have enough material, you can make a good assemblage or installation,” he says.

So is making art all that easy? Perhaps not, but it needn’t be complicated or over-categorised. “Everything I do is some sort of assemblage,” Jack says. “Even The Hungry Years—they’re good because they’re next to each other in an interesting way.” The pandemic brought back memories of the AIDS crisis, where death loomed and created a new creative drive. “That sense of impending doom and urgency made me create The Hungry Years,” he says. “It’s the same thing with these lockdown collages: ‘what would you most want to do if the world was ending in a couple of years?’ That sense of isolation freed me.”

The collector’s edition of ‘The Hungry Years’ (2022) is available to buy now from the Damiani online store, while the original is available from Artbook.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more photography.

Credits

Photos: Copyright Jack Pierson