“Do a job you love and you’ll never work a day in your life,” someone supposedly very wise once said. But it turns out they weren’t so full of wisdom after all; as many a journalist, artist, charity worker and musician can attest to, doing a job you love in actual fact often means never having a day off. Increasingly it also means being underpaid, on an insecure contract and with an unrealistic workload to manage — not to mention a boss who doesn’t get what you’re making such a fuss about. So why is it often our so-called ‘dream jobs’ that end up being the stuff of nightmares?

While exploitation and bad bosses can be found pretty much everywhere you look, we can find ourselves most surprised when they occur in supposedly progressive or creative jobs, highlighting a kind of hypocrisy on the part of organisations who claim to have a higher moral or artistic purpose. In 2020, feminist fashion blog Man Repeller and women-only networking club The Wing both faced a reckoning over their treatment of women of colour, having initially been hailed as the new fronts of feminism. Just a few years prior, major UK charities Oxfam and Save The Children found themselves at the centre of scandal in the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, when former workers blew the whistle on sexual misconduct, both within offices and on the ground in countries receiving aid. And who can forget when Bon Appetit, the fresh, shiny, social media friendly cooking vlog, burst into flames after former employees spoke out about a toxic and racist culture?

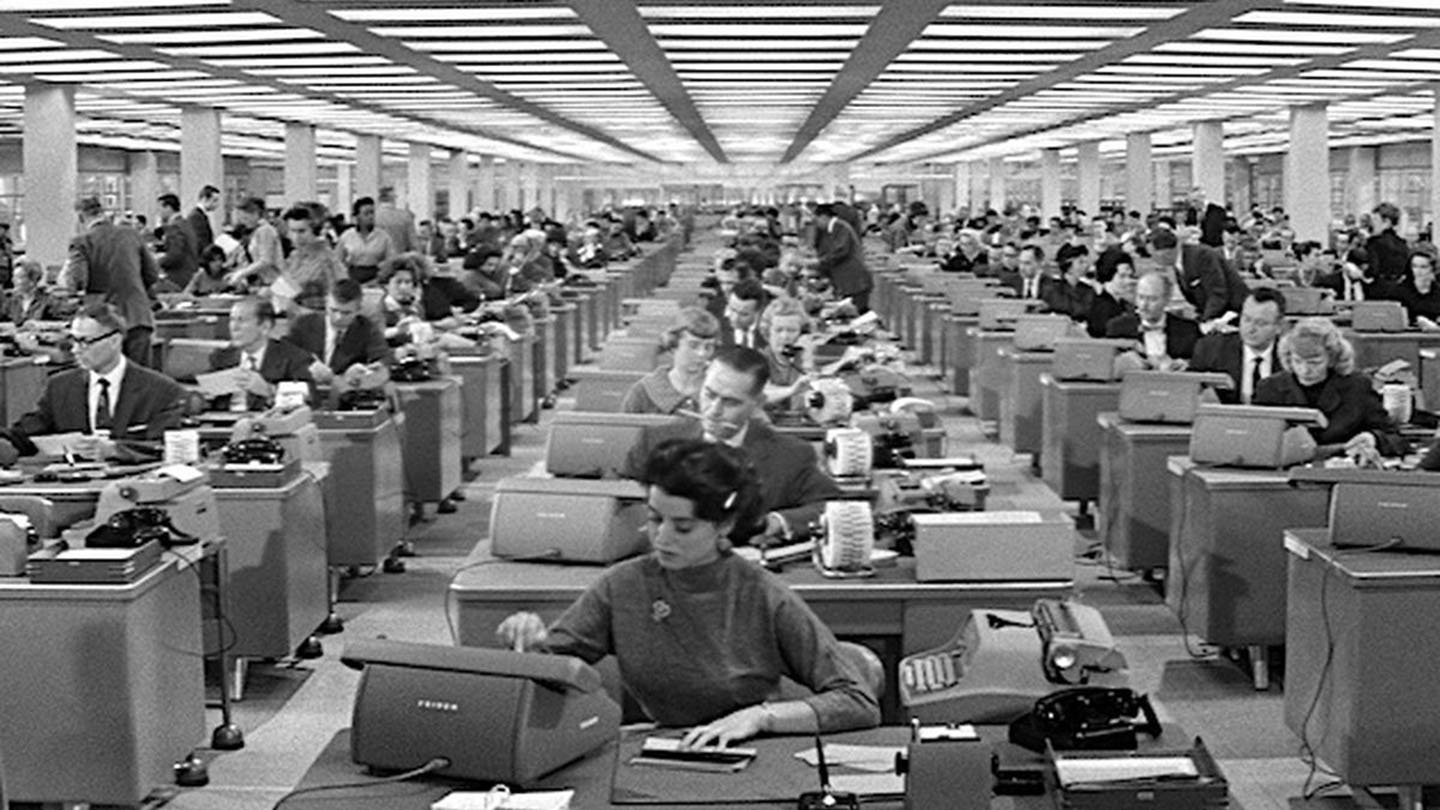

Really, though, none of this should come as a surprise. All work under capitalism is inherently unequal and relies on bosses getting as much as they possibly can out of their workers for as little pay, freedom and control in return as possible. That dynamic might be more obvious when big businesses rake in huge profits off the back of underpaid staff, but it’s still the same even when there are no profits to be made or when the workplace is a tiny shoestring operation. In fact, just as it is workers who make profits for businesses, in the creative and philanthropic sectors, it is workers who generate impact for charities and enjoyment for audiences. In many cases, the outward success of a non-profit or arts organisation might be directly linked to how exploited its workers are.

Unlike jobs in the public sector, where unions have been well established for decades, workplaces like charities, arts organisations and media outlets tend to be newer and younger, with little or no union presence and hardly any infrastructure themselves. Lots of these workplaces outsource functions like HR and payroll, and have barely any policies about how staff can expect to be treated. Small and precarious budgets often mean workers are on short-term and insecure contracts, and managers are given an incentive to save wherever possible, and to do more with less. Add all this to the moral imperative at the heart of charities and so-called progressive organisations, and you quickly find a situation where everyone is overworked and underpaid — the catch being that nobody wants to be the person who complains about a workplace that’s doing good and important work.

And of course, that good and important work matters to workers themselves too. Lots of us dream about jobs in the charity or non-profit sector because we want to do something worthy and to help other people. It’s an admirable aspiration but under capitalism, it’s one that can also be weaponised against us. A friend I caught up with recently recounted how her job in a development charity had become unsustainable due to low pay, long hours and unrealistic expectations from bosses. These demands were justified by managers as an essential part of their ‘vital global mission’, and workers who raised concerns were made to feel guilty and questioned on whether they cared enough about the organisation’s mission for equality and economic justice. Apparently, the irony of progressing this mission by underpaying and exploiting their own workers was lost on them.

In some workplaces, this dynamic occurs even more cynically, in the shape of apparent perks and benefits which often exist in place of strong rights and protections. Who hasn’t heard about a start-up with free beer and air hockey on demand, but a questionable office culture and a horde of zero-hour contracts? Desirable industries like fashion, media and the arts work with the knowledge that plenty of people would kill for a job with them. In the case of many an unpaid internship, for example, workers literally pay for a role in their ‘dream’ organisation, forking out hundreds if not thousands on travel and accommodation just to be unpaid, yelled at by people more senior, and invited to industry events only to hold coats or doors all night.

The conception of ‘dream jobs’ and ‘empowering work’ is also one that has damaging impacts more widely. Sex workers, for example, occupy a contested space in discussions of work, with many people refusing to even classify their labour as such. Their opponents reliably draw on notions of dream jobs, with refrains such as ‘nobody grows up dreaming of being a sex worker’ and complaints that sex work is disempowering. These have a real-world impact; sex workers don’t enjoy a full complement of workers’ rights, and those they do have remain under constant attack.

In actual fact, we all have to work to survive under capitalism, whatever that work ends up looking like. Dispelling with the myth of dream jobs and finding our purpose through work might help us think collectively about how to make things better, rather than letting our bosses successfully divide and rule.

So when is a dream job not a dream job? Well, for as long as we live under capitalism, sadly. Of course we all want to feel fulfilled and like we’re making a difference, and there’s nothing wrong with ambition or dedication. But if it turns out not to be all it was cracked up to be, know the problem isn’t you but work itself. Freeing yourself from the grip of the dream job might end up being its own kind of dream.

Follow i-D on Instagram and TikTok for more on work and capitalism.