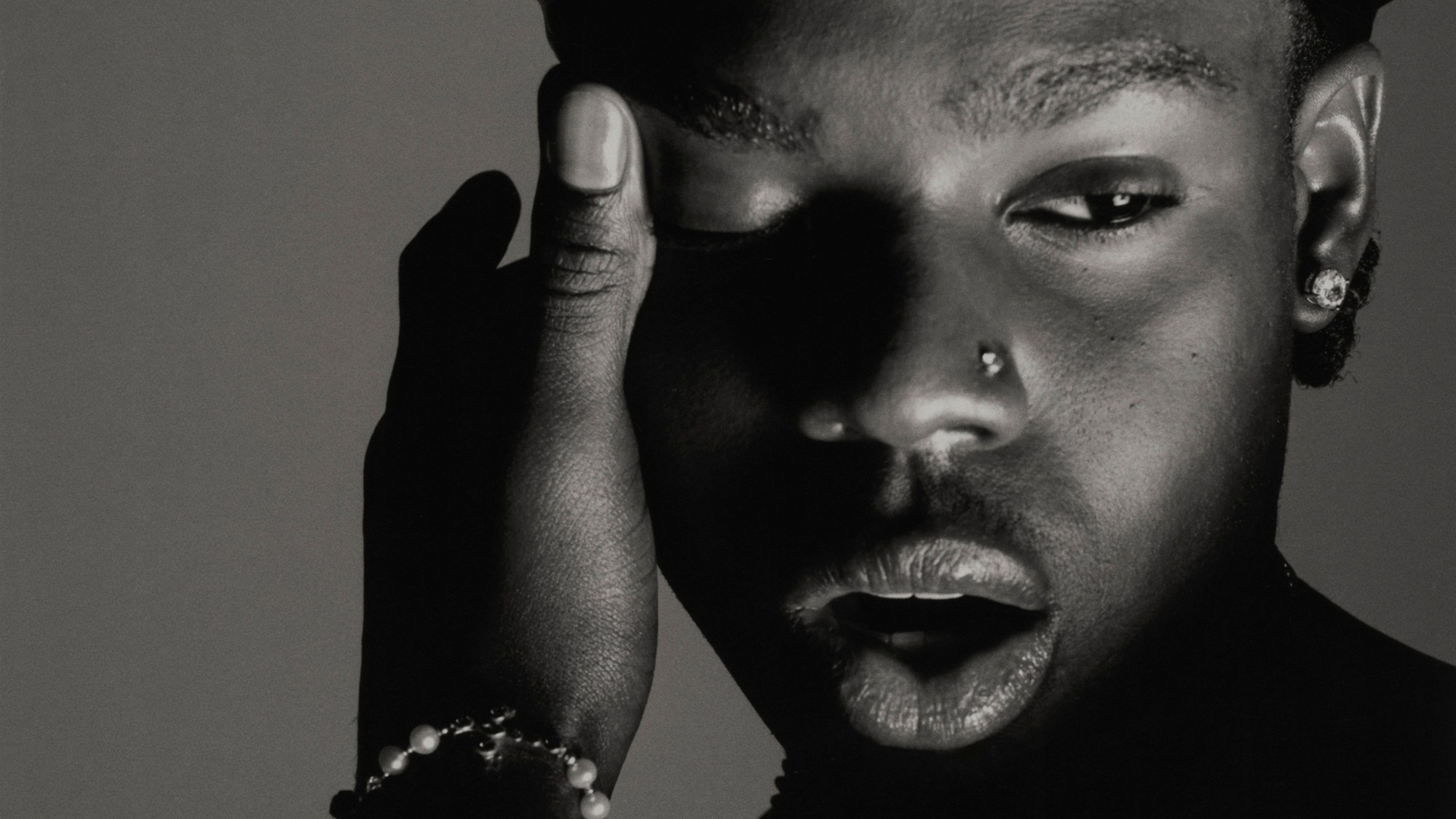

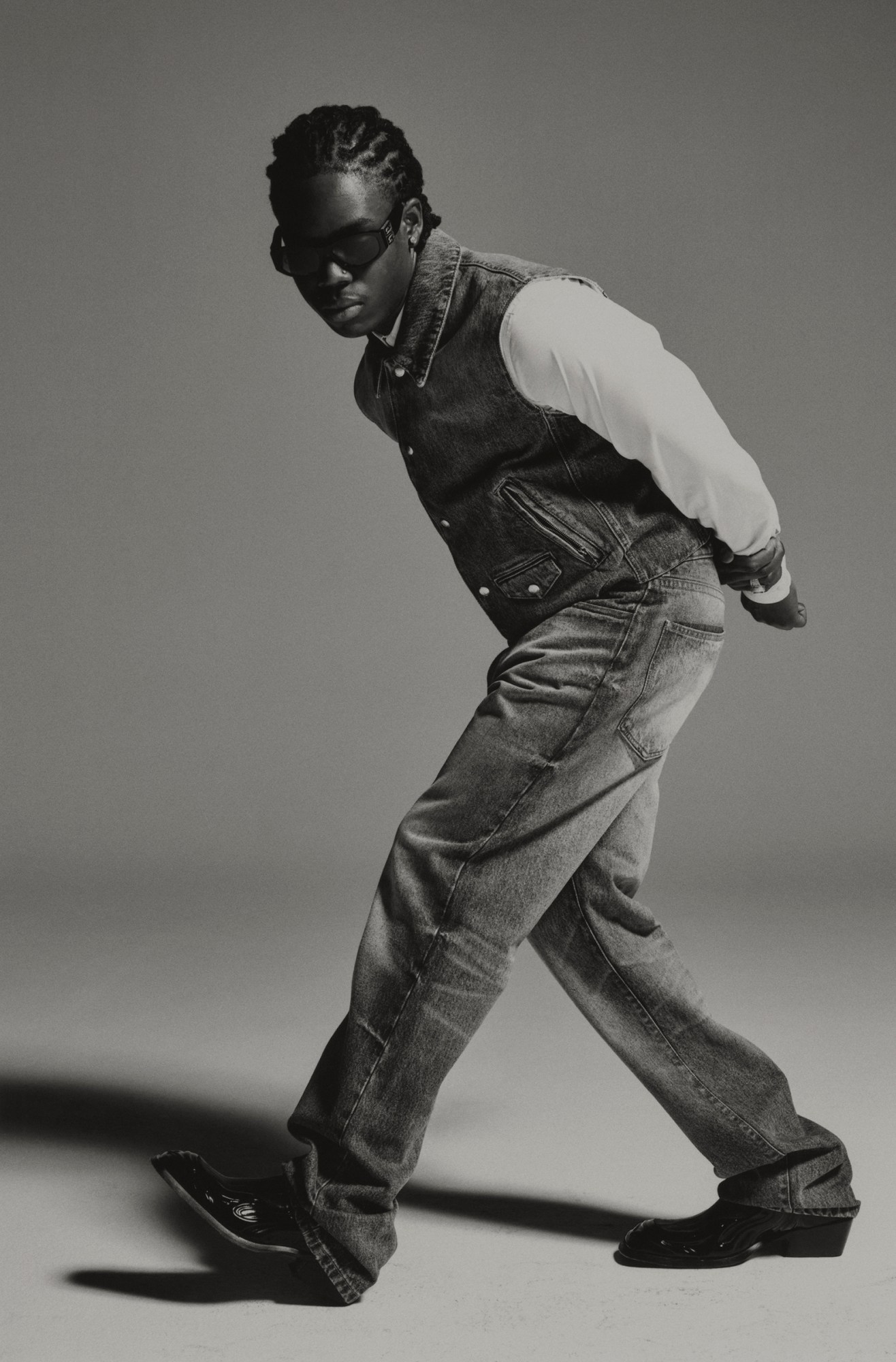

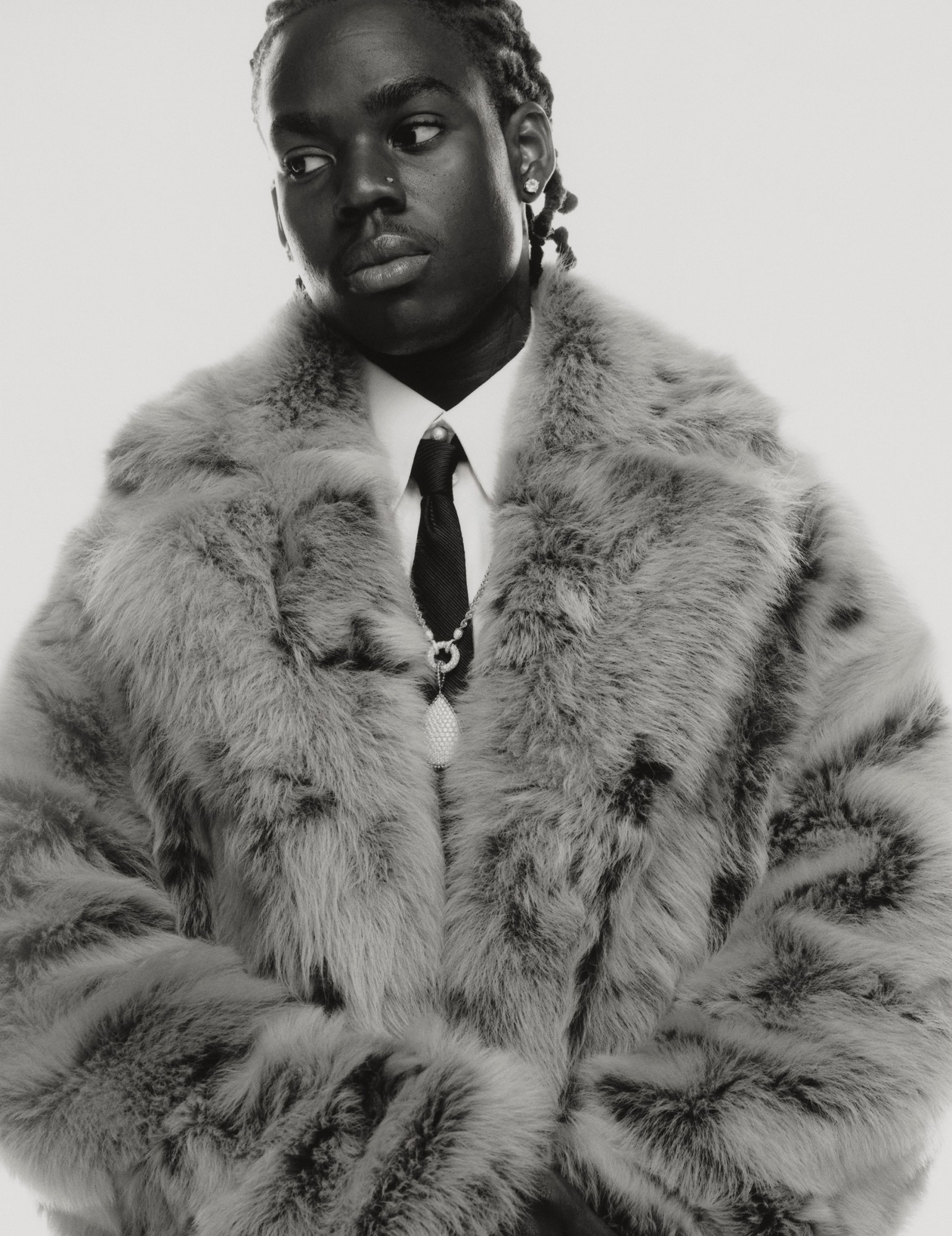

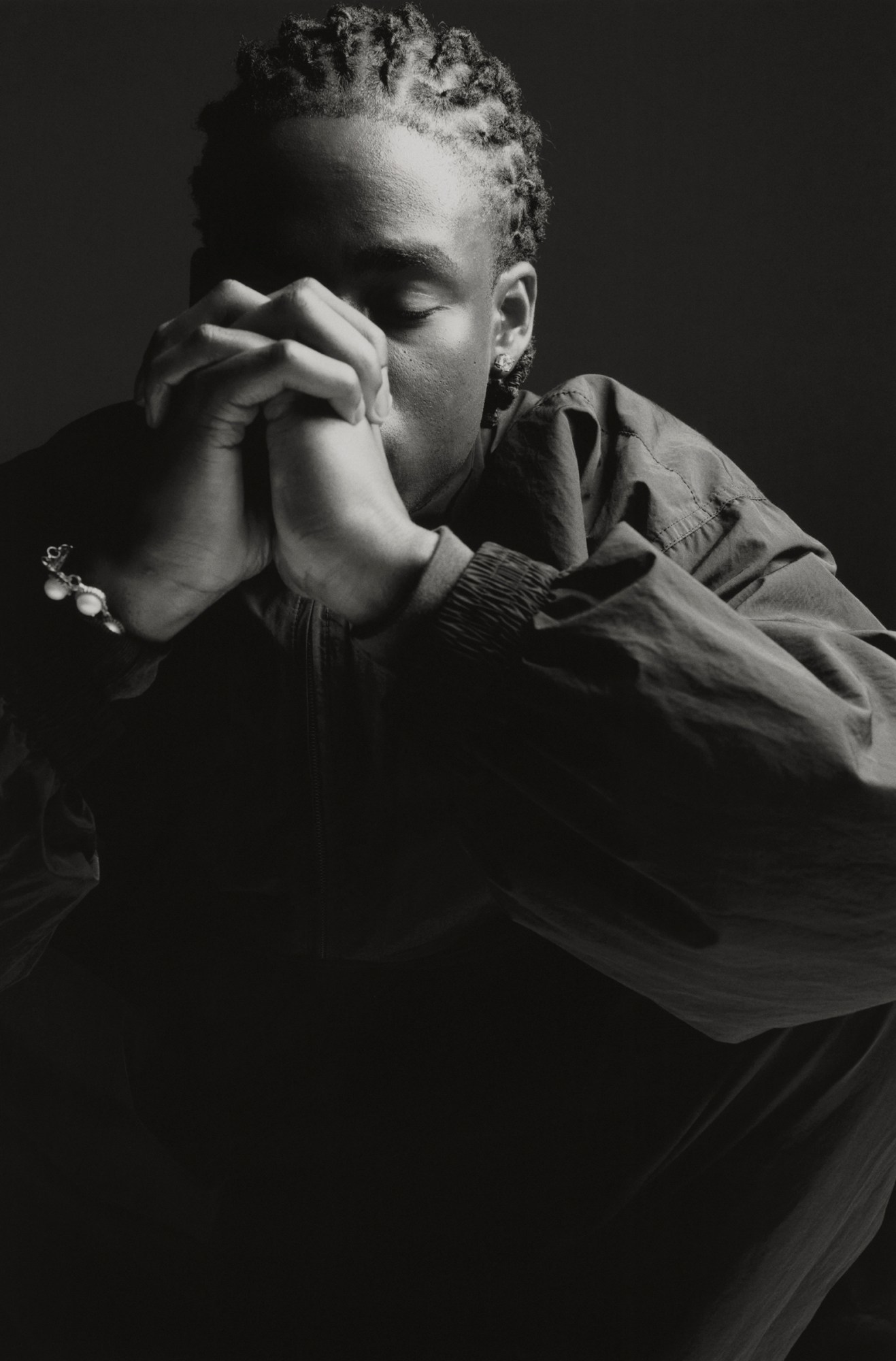

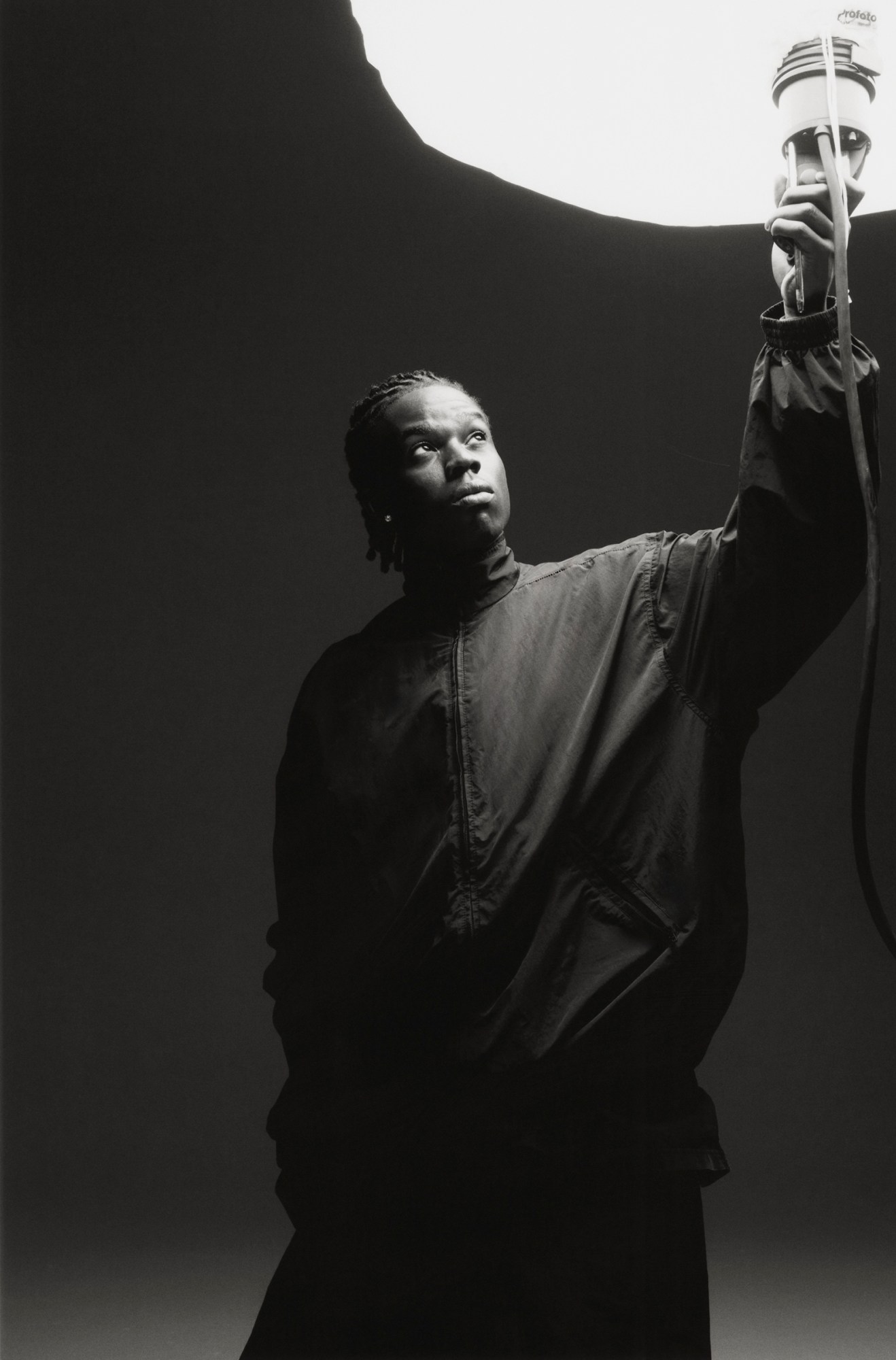

This story originally appeared in i-D’s The New Wave Issue, no. 373, Fall/Winter 2023. Order your copy here.

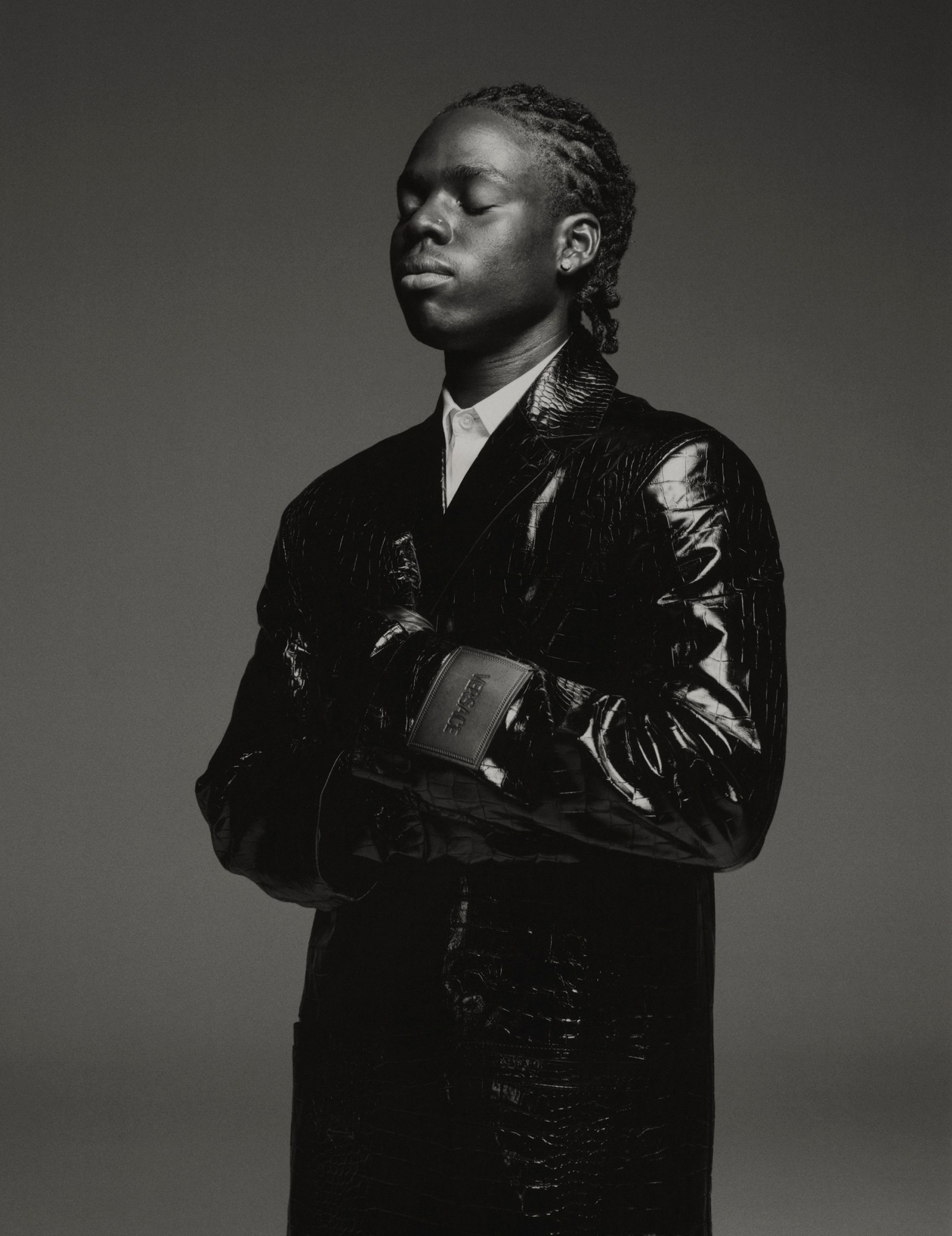

Rema seems to know exactly what he’s doing, even when he won’t explain himself. The Nigerian singer and rapper moves with intention; he is acutely aware of how he is perceived, and he is more than willing to let his plan reveal itself to sceptics when his work proves them wrong. He doesn’t like to talk about himself. That’s intentional too. He likes the focus on his music, and with good reason: he has formulated a sound that speaks for itself. As we chat about his perpetual drive, he is taking a short break from shooting videos in Los Angeles to get a new tattoo. Soft-spoken but firmly resolved, he only ever gets animated speaking on the trails that he is blazing for others, both those that came before him and those who will come after. “A legend talked to me and he said, ‘Oh, I really like what you did for Afrobeats. A lot of people will not tell you this, but you helped me,’” he says. “It’s all about who’s going to say the truth and who’s not going to say the truth. I don’t care because I can see the back end, so I already know my impact.”

At only 23, Rema is already one of Afropop’s greatest ambassadors, a next gen innovator and one of the biggest artists on the planet. He spent his summer playing festivals across Europe and touring America. More than once, he talks about his shows as a symbol of his expanding influence, as a means to represent where he comes from. Culture has power. Just as the Korean Wave has increased South Korea’s international standing, the pop music of Nigeria is beginning to have a similar effect. To Rema, every new place that his music touches is a greater win for Nigeria, and for Africa.

Born Divine Ikubor, Rema is from Benin City, among the oldest cities in Nigeria —the remnants of a pre-colonial kingdom. “It’s a place of history and tradition. A lot of hardship, a lot of suffering. But the people are warm people. There’s much love in the community. Everybody knows everybody. It’s a place of big talent, most especially in sculpting, in bronze art and music,” he says. It isn’t a stretch to say that Rema is the most renowned artist to come from his hometown. He thinks fondly of its people and the way they communicate: “Nigeria has, like, 156 or more cultures, but the people are distinctive in the way they talk, the way they behave, the jokes they make, the way they react. They’re very expressive. They make up a lot of words, and when it’s popular, it’s a thing. We’re just fond of creating words and sound effects.” It’s somewhat fitting, since creating words and sounds has been Rema’s purpose for quite some time now.

Rap and spirituality were pillars of Rema’s upbringing. Those worlds collided early when he first began performing in a church program called Rap Nation, rhyming to gospel songs as a draw for young potential churchgoers. He was introduced to trap by cousins, and he parrotted his older brother’s embrace of hip-hop fashion. Rema was drawn by the look as much as the sound, and in time rappers like A$AP Rocky and Playboi Carti became influences for his own personal style. The serious pursuit of a rap career became top of mind, and he eventually started using a phone he got from a member of his church to download beats he would freestyle over.

Tragedy struck when Rema became a teenager: his brother died in a mishandled procedure and his father, Justice Ikubor, a politician connected to the People’s Democratic Party, was discovered dead in a hotel under mysterious circumstances. The deaths left Rema’s family struggling and prematurely made him the head of his household. He tried to win prizes in rap competitions, busked in bars, and sought out stages everywhere from lounges to political rallies, focused on feeding his mother. Over time, he lost the urge to do music; feeling the heavy burden of being a breadwinner too soon, he took off to Ghana, where he did any manual labour he could find. Alone and far from home, he scrounged together enough money to return to Benin City as a provider.

In 2018 a viral Rema freestyle, recorded on a whim and uploaded to Instagram, suddenly sparked his music career anew. The Gucci Gang remix caught the attention of the song’s original creator, Afropop legend D’Prince, who has had a hand in two of Nigeria’s most influential labels, the defunct Mo’ Hits and the modern powerhouse Mavin Records. What began as mere punchy rapping slowly mutated into a liquid singsong — the verse was raw but he could see the vision. After coming across the video, D’Prince flew Rema out to Lagos to say that he loved his voice and that he felt he should embrace Afrobeats. “I played him my rap stuff and he was like, it really suits me doing Afrobeats. And I was like, that’s not my sound. I don’t want to do that,” Rema says. With that, he went back to hustling in Benin City, but D’Prince would not be pushed back; he reached out to Rema again, presciently told him that he could change the world with his sound, and asked him to trust that it would all work out for the best. It did almost immediately. “I started making Afrobeats stuff, and then the second song I did was Dumebi.”

Listening to the self-titled 2019 EP that produced Dumebi now, you can hear an artist in transition. There are flashes of his affinity for the SoundCloud rap of that moment in the States, but he seems to be tinkering with the sound of the future in real-time, one that effortlessly integrates melodic trap with the subtle sway of contemporary Afropop. The Freestyle EP made his rap influences plain that same summer, and by that fall, with the release of Bad Commando, his mastery of the two styles was verging on alchemy. Each new turn in his music has never strayed too far from his hip hop origins.

Even today, Rema sees rap as the bedrock of his progressive work. “Whatever sound that I have with Afrobeats, it’s still an evolution from whatever rap sound I had. Even if you listen to me from 2019 to now, the sound keeps evolving,” he says. “I don’t see it as me being a rapper—I see it as me evolving from a rapper. And the sound still walked in me because even when I dropped my first song, I was different from everybody else.”

Being different initially rubbed traditionalists the wrong way. His music pulled from rap in a way that was original and unfamiliar, challenging the status quo. Songs like Iron Man led some to characterise his sounds as Indian. He says it didn’t bother him, but it’s apparent that he turned the slight into fuel, and that it’s still a chip on his shoulder. “The energy was that they’d get it eventually. I took it as motivation,” he says. “When you play a video game and you see the bad guys shooting at you, you know that’s the right way. Everything they doubted, everything they laughed at me for, I built on it. They called me Indian Boy; I went to India. I’m the first artist to shut down four cities in India, 5000 capacity and above. No one can deny that I’ve impacted Afrobeats on a global scale.”

Afropop, particularly the pop of West Africa, has broken through in the 2020s, thanks in large part to Rema. He is on the tip of a breaking wave that has brought the sounds of the region to shores everywhere, a movement nearly 20 years in the making. The success of P-Square, and Mo’ Hits artists like D’banj, Wande Coal, and D’Prince in the mid-2000s, gave rise to a fresh crop of breakthrough stars the following decade. Their efforts birthed what has come to be known as Afrobeats, a fusion of sounds and cultures. Davido, Wizkid, Olamide and Tiwa Savage led the charge in the early 2010s, experimenting with chintzy blends of R&B, pop and soul that incorporated some hallmarks of African music. There were a handful of classics made in that span, but the genre didn’t really find its footing until 2016. That same year, it started to make its mark in other countries when Wizkid appeared on Drake’s “One Dance”, the number-one song in the world that year, according to the IFPI. By 2021, Burna Boy was a Grammy winner.

If there is any direct precursor to Rema, it’s Wizkid. The comparison was made early and often — perhaps too often. Wizkid is a titan, and there is a real resemblance, but Rema is much more efficient in his manoeuvres, and more deliberate in defining his sound. His is a particularly transmutable pop, as aberrant as Young Thug, but as hooky as Drake, taking the genre where no artist has before: complete synthesis. Still, Wizkid and his peers set the stage for artists like Rema, the crooner Fireboy DML, and the shapeshifter Amaarae to bring about a pop revolution, and Rema is not oblivious to the footprint of his predecessors.

“They set the tone sound-wise. They set the tone brand-wise. They set the tone on chasing the global dream.” He has a clear sense of admiration for those that cleared a path for him. “That’s the power of building a strong community. It doesn’t take one. It takes a lot of people to be able to build it, and I’m building off of that.” His contributions have opened the door even wider.

There is a lot of talk about labels in Afropop. Some shun the Afrobeats tag while others embrace it. Many artists come up with personal descriptors, hoping to define their music for themselves and distinguish it from everything else. Rema has called his music Afrorave, an updated version of Afrobeats that is exceedingly finespun and tasteful. “Afrorave is my perception of African music,” he explains. “It’s from the roots of Afrobeats. I cannot deny the inspiration from Afrobeats and the Afrobeat legends. So it’s like, I’m just taking it up to the next level, which every generation is supposed to do. Literally, it’s how I see it, how I hear it, how I feel like it can evolve, how I feel like it can change, how I feel like it can appeal to the people that it didn’t appeal to generations before.” It’s clear that his music is appealing to many. In April, Rema’s debut album Rave & Roses became the first African project to hit one billion streams on Spotify. A remix of the album’s single, “Calm Down” with Selena Gomez, went number one in nine countries.

Rema says his goal is the same as everybody else’s: “To leave a mark in the world.” “It’s not about the trophies or the girls or none of that. One of the main goals is to touch generations to come. Whether I’m here or whether I’m not here,” he adds. “To be able to inspire people to keep creating greatness. That’s the number one thing. Beside that, we aim for the trophies just to be the biggest artist in the world. And when you’re the biggest artist in the world, it’s not really about being the top dog. It is more about reach.” From the way he talks, it’s clear the artist understands the extent of his reach — but also that he is eager to continue to expand it, and is aware that trophies are a handy way to keep score. He’s amassed a few this year: Artist of the Year from two different African award shows and the inaugural winner for Best Afrobeats at the MTV VMAs.

Rave & Roses is the catalyst for all of this. The album feels like the target Rema has been aiming for this whole time — rap-adjacent, mood-forward, rhythmic yet sashaying, powered by his silvery voice and fluid performances. His singing has a soothing quality, but the tricky way he navigates beats isn’t unlike such rappers as the late Juice WRLD. Creating these songs, as for most rappers, is an unscripted process. “I just make stuff,” he says. “When I get time with my boys, we make beats and we laugh, and we talk and we play and we vibe. But I never work in the studio with writers or serious energy. I just have a good day. I just go up in the studio and create. I don’t overthink nothing.”

For Rema, vibe is paramount. But it isn’t just about atmosphere; it’s internal. “When I hear the beat, when I feel the emotion I want to tap into, I dwell on it,” he explains. “There’s no magic about it, really. I feel like a lot of people hear my sound and feel like, ‘Oh, it’s really so deep’, you know what I mean? ‘He has candles lit up,” or something. But it’s like, the real power is in me. The real juice is in me. And I feel like if anyone followed me to the studio session, they would take nothing home because I’m the source.”

Rema is not bashful about his talent or what he’s accomplished but his big talk belies a softer, more reserved side that is pursuing understanding. Rave & Roses was inspired by love — feeling it missing and seeking it out. He felt like it was something he lacked, lost as he was “chasing dreams”, and he tapped into it wherever he could find it. There are, of course, songs about sex and songs in admiration of a beautiful body, but it feels like he’s mostly talking about a song like “Hold Me” with its subdued, warbling petition for support, or “Divine”, which recounts the story of his birth as a source of fortitude. “I felt pain when I lost my father / I felt pain when I lost my brother / I felt weight stacking on my shoulder,” he sings. “Omo it kept growing as I got older / The voice in my head told me I’m a soldier / Then I remember the time mama named me Divine.”

He says the album will be appreciated even more as he continues to release music, and that listeners will start to make connections. “I’ve been able to let things out, because on a real note, I do not talk. I’m quiet. I don’t share no stories. I don’t express nothing. If I’m hurt, I still smile like nothing. Nobody knows anything about me. I feel like slowly I’ve learned more about life. I’m growing up to be a man. I feel like anyone who loves my music will get to understand my point of view, understand my hustle and everything over time.”

But even at a remove, his music has deeply resonated with people. Earlier this year, a clip of a sell-out crowd singing “Calm Down” word-for-word spread across the internet. As they sing, Rema stands before them, beaming as he takes it all in. When asked what he was feeling at that moment, the emergent star speaks of the euphoria of recognition: “Gratitude — seeing what you created in your bedroom being appreciated globally. Seeing it happening to people in different ways. People who speak different languages singing the song—there’s no other feeling but to feel blessed, but to feel chosen.”

“What’s really crazy is that I’m a person from an African background speaking my own language and doing my own thing being able to touch people from all cultural backgrounds. From Africa,” he says, stressing that last part. “That’s what’s iconic. And now, being able to do it on a global scale, where you touch everyone at once. I see Africa just going forward and forward from there. And the stereotype will be cleansed as well.”

He is well aware that this is history in the making, and that the influence of Afropop is pushing back against long-standing characterisations of Africans. Even more so, he knows that history now can’t be written without him. “I’m not saying I want to stop. But if I say I want to stop right now, my name is still going to be on the Afrobeats bible, if there is an Afrobeats bible to be dropped,” he says, nodding to his Christianity. “I’ll literally be in the New Testament, on the front page.”

Despite that, Rema still wants to do more. “The clearest vision I have right now is that I will open so many new territories to Afrobeats. A lot of artists have been to major cities, but not smaller counties. I’ve performed in counties with a population of 1000 people, ‘cause my music could go there. That’s the vision for me: opening doors, creating bridges. I’m the bridge to a lot of undone things. I already put in the work and I know what is yet to come from me, and I’m ready,” he asserts emphatically.

“This is the clearest vision I have,” he reiterates after a pause, as if choosing his words carefully. “I have other visions, but there are some visions that are better done than said.”

Credits

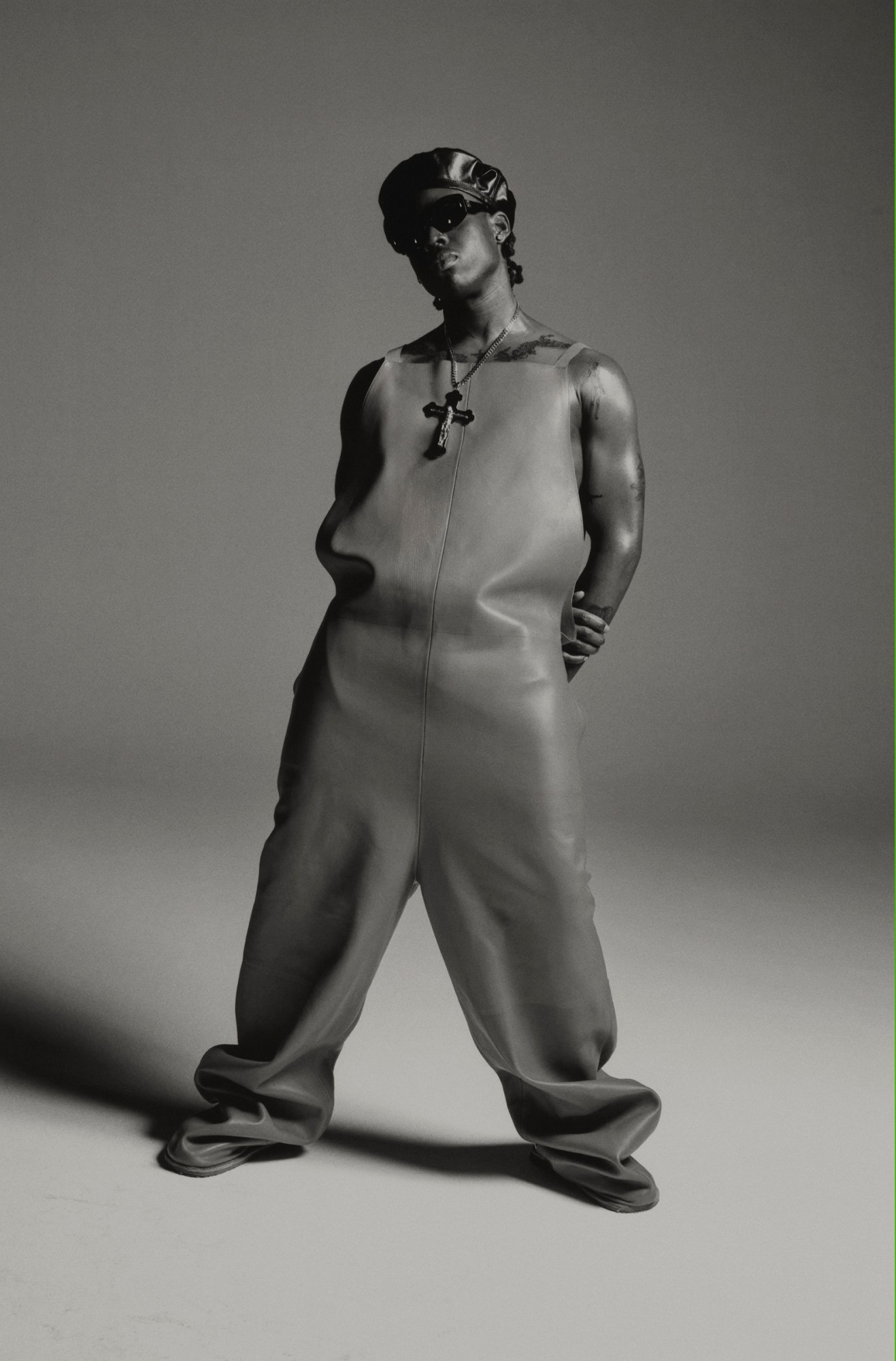

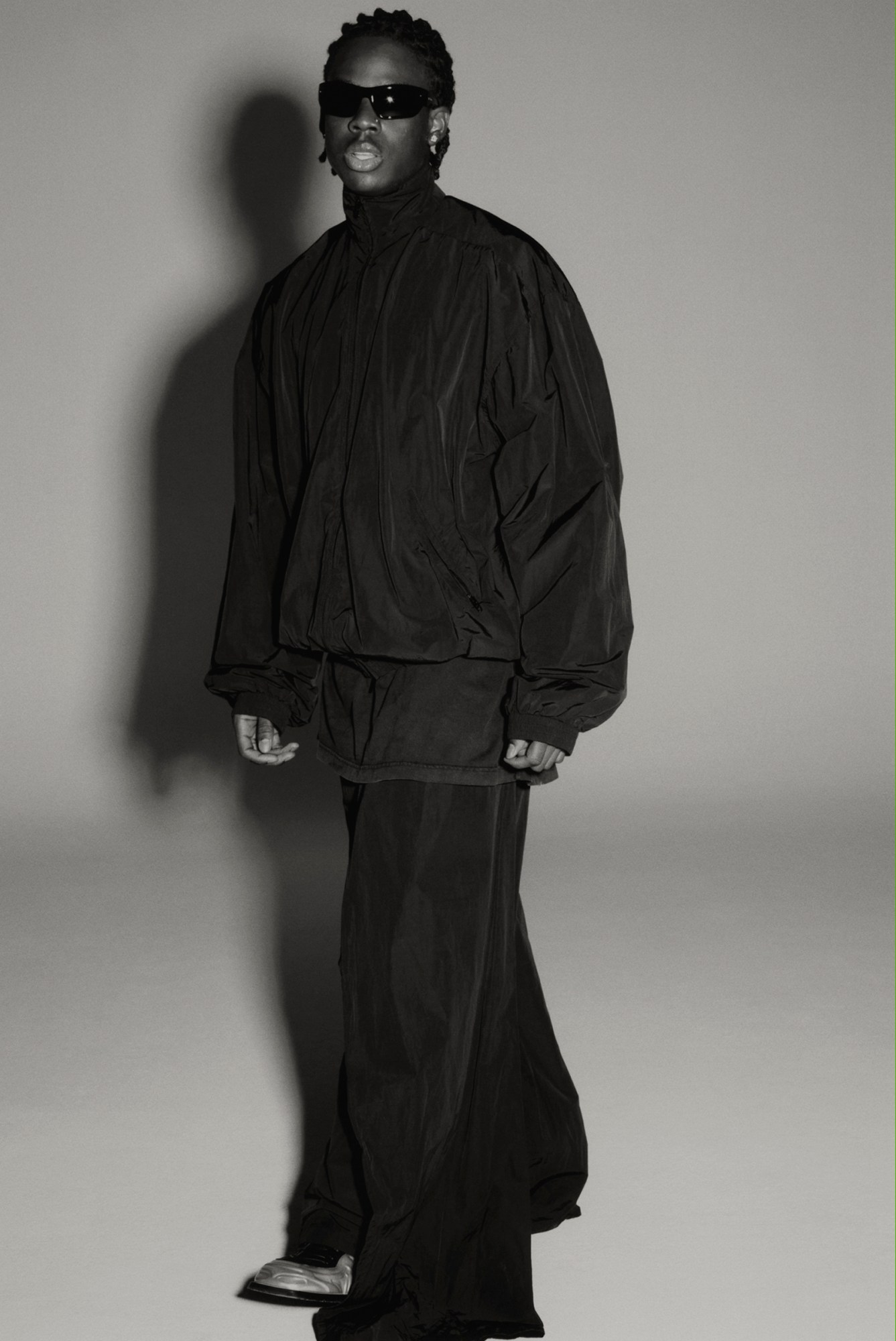

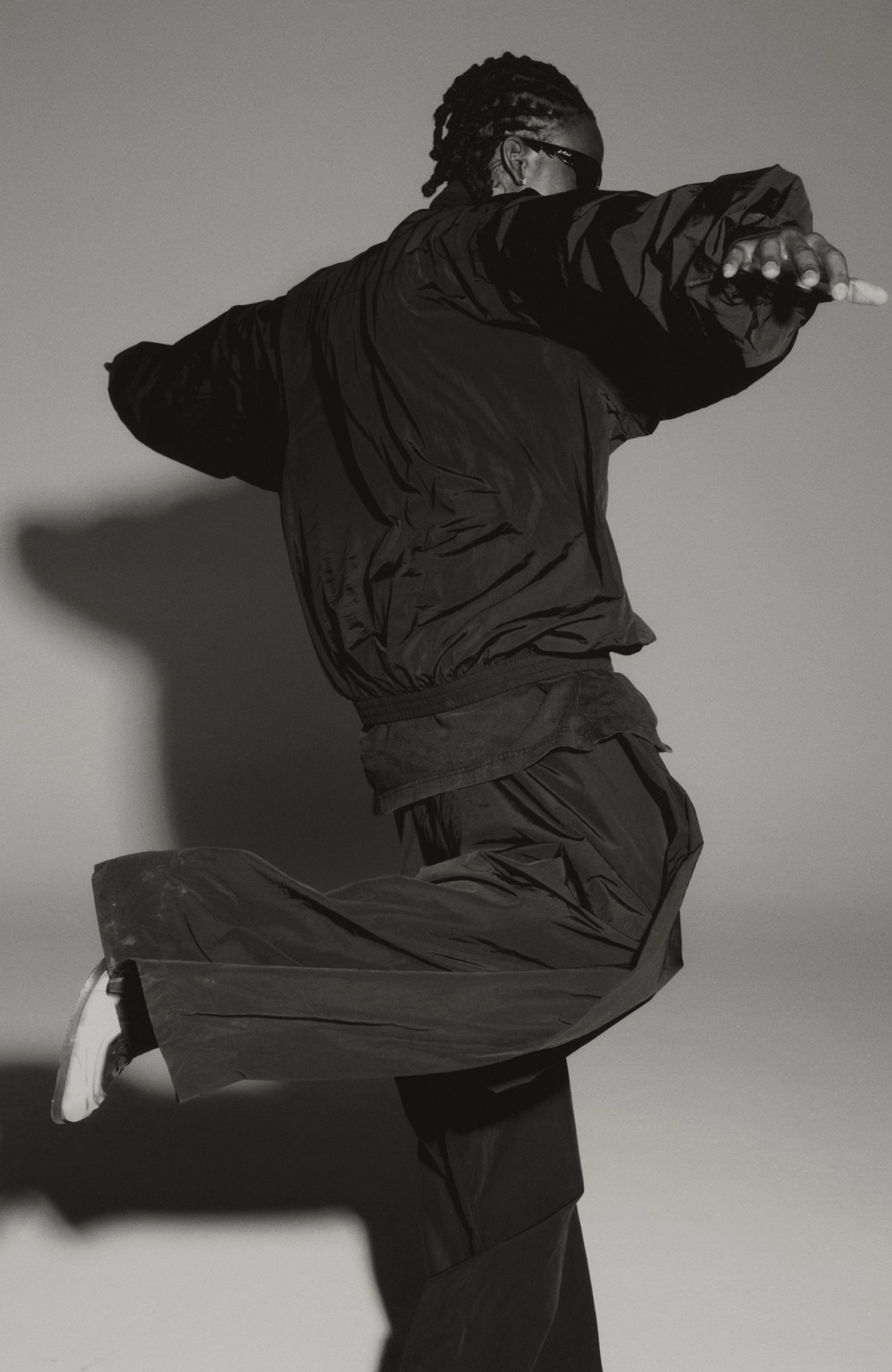

Photography Renell Medrano

Fashion Carlos Nazario

Hair Benjamin Muller at MA+ Talent

Make-up Yadim at Art Partner

Photography Assistance Andreas Strunz and Moira Laurent

Fashion Assistance Martí Serra, Christine Nicholson and Emilie Carlach

Hair Assistance Mills Mouchopeda

Make-up Assistance Paloma Romo

Production Ice Studios

Casting Director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING.