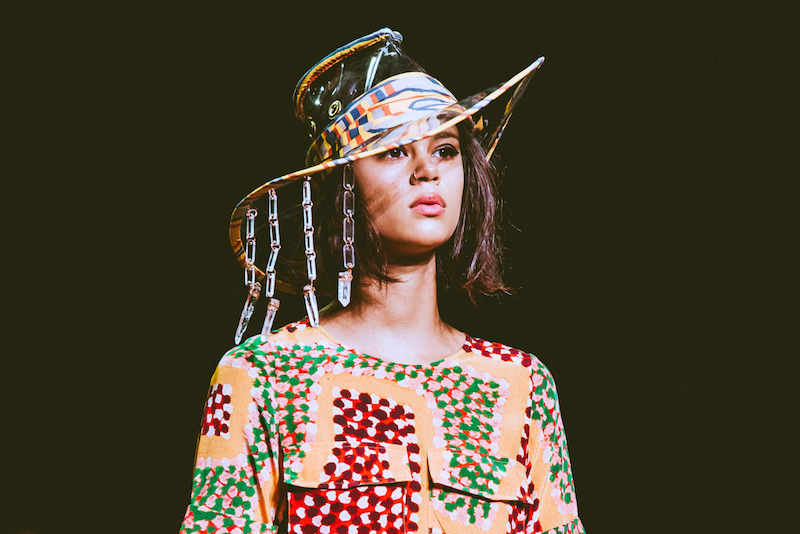

Desert Designs shone in the 80s amidst the country’s blooming appreciation of traditional Australian art. In 2013 Desert Designs was relaunched under the guidance of co-founder Steve Culley’s daughter Jedda Daisy and her childhood friend Caroline Sundt-Wels. The women have continued to uphold the label’s strong history, while creating clothes that are vibrantly modern.

Hey Jedda, so how did your dad and Jimmy start working together?

They actually met in maximum-security prison. Jimmy had a seven-year sentence and dad was in there teaching art. Dad began with no students – he was this long-haired hippy in the 70s – but gradually his classes became so successful that he had 120 prisoners in each. Jimmy was running the indigenous version of the art class and dad was just blown away by everything Jimmy created. Dad gave him Texta pens and the fluorescent colours and vibrancy related to him as the intensity of a desert landscape. He was producing incredible works of art and dad started holding exhibitions within the prison so outsiders would come and purchase the artworks. They were worried about the archival nature of Texta so created limited edition prints using silk screens. My mum was printing the fabric and made me some dungarees when I was born, that was the beginning of the company.

Were there implications with your dad promoting Jimmy’s work?

At the time it was quite a radical thing to do. The fact Jimmy may have been a murderer was never publicised and I can’t think of a time he was criticised for it. Jimmy was one of the first indigenous artists to become financially successful and independent because of these exhibitions and Desert Designs. Dad and Jimmy were such good friends and Jimmy approved everything so there were no issues.

How closely did Jimmy and your dad work together on the fashion?

Jimmy wasn’t particularly interested in designing clothes but he was very interested in wearing them. I remember when I was a kid he was quite a fashionista.

How did the indigenous communities feel about Desert Designs?

It allowed Jimmy to put a lot of money back into his community. I remember seeing so many people wearing Desert Designs where he lived in the Great Sandy Desert growing up. Jimmy was so proud: he’s painting his picture, wearing his picture, it’s a good little image.

What led to the brand’s renaissance in 2013?

My friend Caroline was discussing the idea with my dad and they decided to just do it. I’d just finished my Masters at the College of Fine Arts and was on track to being a conceptual artist. Suddenly they were doing this and I was like, “hang on why aren’t I involved?”

With Jimmy now passed away, how does the licensing of his prints work?

The Jimmy Pike Trust is run by Jimmy’s wife Pat. My favourite aspect of the business are our conversations, she is an inspirational woman. She’s intelligent, she’s written so many books, she’s a mind-blowing woman. Everything gets approved and is paid back into this Trust – essentially it’s the same way it’s always been.

Is it difficult to evolve and personally be fulfilled by the work whilst trying to honor the history of the brand?

I don’t think it’s hard at all [laughs]. I’ve been so inspired by indigenous culture and it’s opened doors for me because I’ve been involved since I was a child. Jimmy’s work in particular has been inspiring, you don’t think of him just as an indigenous artist—but as a contemporary artist. You compare him to someone like Matisse. He’s a colourist and colours are what excite me.

It’s easy to get caught up in the cultural side, but he should be viewed in the same realm as any artist. There’s been debate about cultural appropriation with brands: taking images and iconography from other cultures and appropriating them. How do you manage that?

This has been a huge issue for me, it’s what I care about most and find most sensitive. I have Pat guiding me through this, and any time I have a question I run it past her. We have strict boundaries with Jimmy’s artwork. We can’t introduce another colour. If there are three colours in the work we can’t introduce a fourth.

I was really surprised that of all the prints from your new collection were Jimmy’s originals, they feel so contemporary.

I know, it’s mental. I don’t see it ever dating. We have an archive that’s over a thousand images deep.

What do you think of the trend of caucasian kids becoming really inspired by indigenous cultures? Is it paying homage or trivialising it?

This is a really interesting question. Worry for our natural world dominates our popular consciousness, people are obsessed with eco-friendly products and “organic”, it’s what we need but in a sense it’s become a trend in the mass media and in the marketplace. People can’t see a solution, maybe we need to look to alternative philosophies and methods of living, maybe it’s just a natural progression to look at other cultures.

Your dad worked with Jimmy and there’s a trust that feeds back into the community; whereas if you look at a culture, take something, profit, and get in your car to drive home it’s different. I think this debate seems more ferocious in Australia because we’re so young.

Yeah, the wound is fresh still. I always ask my dad about it, but he never experienced the political hysteria we do, the drilling questions like: “how much are you paying him?”. I respect the questions and believe this is what gives our brand credibility. Dad’s just never experienced it before which I find that interesting. He was always doing the right thing.

Credits

Text Wendy Syfret

Photography Marcus Soloman and Solange Knowles photo by Mikki Gomez