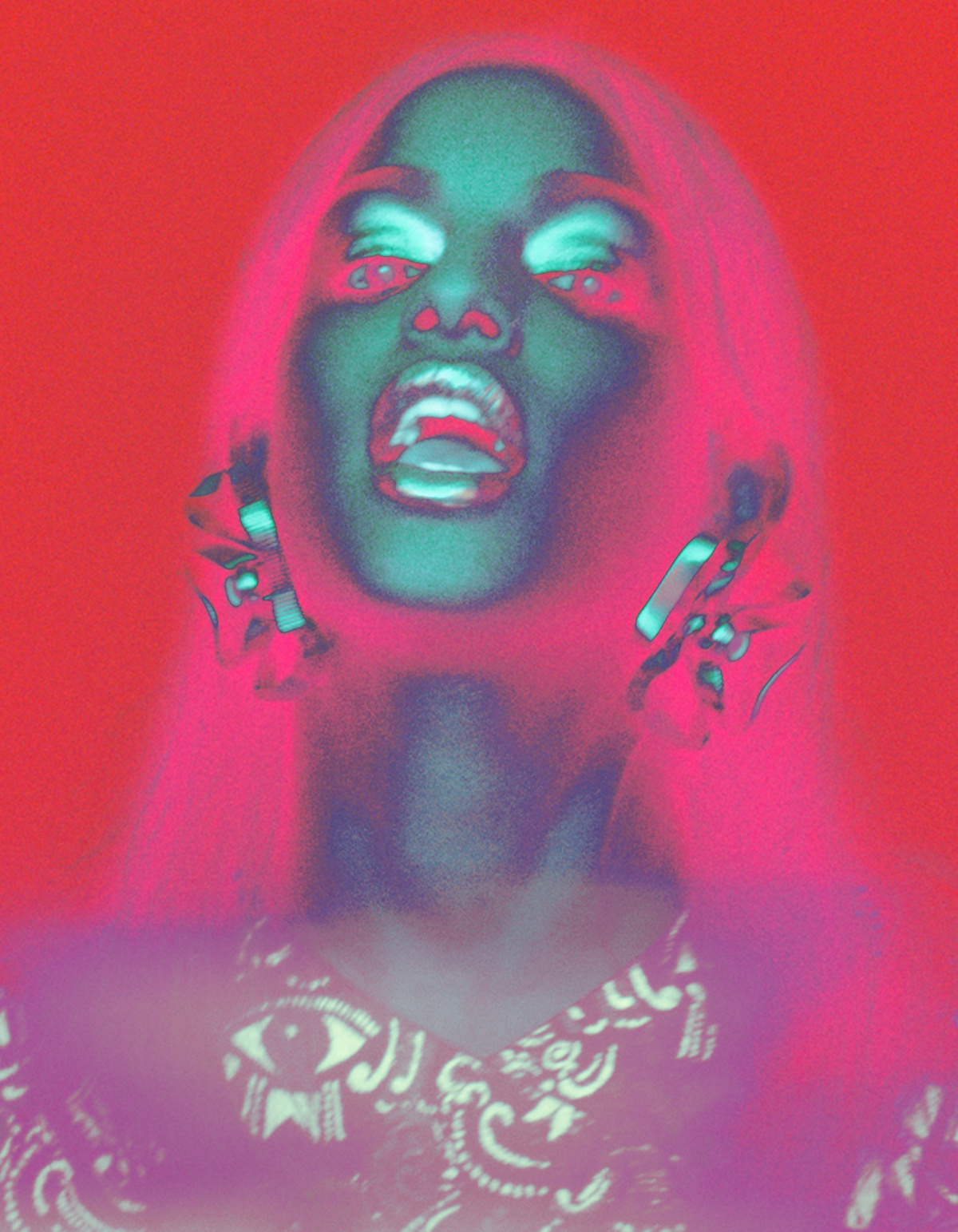

In 2011, just after she released her Vicki Leekx mixtape, M.I.A. found a message in her in-tray from Julian Assange. Perhaps provoked by the implied tribute of the title, the Australian activist had sent her an email. She has no idea how he found her email address. “I tweeted about it, saying it was really unnerving handing over your computer to Julian Assange,” M.I.A. notes now, on the top floor of an East London photographic studio. Today her look is an acid green boiler suit, thickly daubed orange eye shadow and jewellery everywhere. She looks the bomb.

When Assange dropped her a line, the opportunity to tap the source material of big international debate was too irresistible to ignore. So she sent him her computer and asked him to decrypt every word he could find with “tent” in it. She offers no further explanation. The results of this odd little collaboration can be heard on her new record Matangi, on a song called Attention in which a panoply of the words he found is recited by M.I.A.’s multi-treated vocals and set against a banging sound-bed.

The Assange correspondence is a useful reference point as a means to understanding the methodology of M.I.A., still the one British pop star who retains faith in the medium as a conduit for proper extrovert provocation. She places her music, with frantic energy, exactly in the moment, all the better that it might be a useful document of something more than nostalgia in years to come. On her last set Maya she had put down on record a prophetic, tough sequence of songs unlocking some of what might be called the entrails of the global Assange quandary, a question nobody else seemed to be asking: what does good and bad mean in the digital age?

You can’t fake it, you have to live it. I live what I put out. As an artist, that’s all you have.

The story of her new song Attention is in a way the story of how pop music once worked, before market share became the primary concern. Someone had an idea, they executed it in the best way contemporary technology could afford. If it worked, bingo! There was your pop record. If it didn’t, everyone had learned something been stimulated in the process. Why M.I.A has not yet become the indigenous star she should be paints a depressing portrait of the British pop machine. She has written one of the most epochal songs of the last decade in Paper Planes, and presented four albums that have a wild imagination, delivered at an exquisitely considered taste level, sometimes raucously unhinged, while staying a faithful mistress to the undeniable fizz of a pop hook. “Yeah, it’s weird isn’t it? I am very unfamous, though. I don’t feel like that when I’m in Tesco’s.”

America has been kinder to her, but back home you could count her influential industry supporters on less than five fingers. The national pop stations don’t play her, yet she’s all over the radio in the USA. Jonathan Ross wouldn’t have her as a guest, yet she goes on Letterman repeatedly. Something like the Mercury Music Prize, which was surely invented to leg up someone like Maya into the national consciousness, hasn’t honoured her, yet she was Madonna’s guest and cunning marketing sting at The Superbowl, the most watched show in the States. She played the Grammys, pregnant, in a monochrome spotted one-piece, but wouldn’t be invited to the Brits. “No, nothing,” she says, a position she has only just began to reconcile herself with.

“I am not part of the mainstream,” she says, before considering for a moment why this might be. “People are always telling me if only I’d shut up I’d be successful.” In her model, success must be achieved on different terms, in the old-fashioned sense of personal achievement and latter vindication. Sooner or later it will happen. She doesn’t shut up. “That would be to lose my experiences along the journey, which I fought for and didn’t want to tell without being completely off-radar.” Pop music, she says concisely, is about “bringing these experiences and validating them.”

“You either go mad or you become a drug addict or you become spiritual. I’ve gone for all three of them. Well, I’m not a drug addict, but I’ve been branded all of that.” After Maya received a routine critical drubbing, and an influential New York Times piece threw a gas canister at the bonfire with a more personally-driven decimation of her process, after Vicki Leekx dropped, after her relationship fell apart, after what could only be seen as her annus horibilis, M.I.A. did what any sane human being would do. She fucked off for a bit with the specific intention of never making another record. She was not so much circumspect about the crash and burn of Kala as going through what sounds like a period of intense self-loathing around it. “People would say to me, OK, this means you’re going to be broke forever, and you’re just going to be a fucking loser crack-head and nobody’s going to care about your shit. Your music’s going to be forgotten, and you’re going to get rewritten out of history like you’re just out of this fucking loop.”

On her preliminary travels to India, a thought began to germinate in her mind. “My whole catchphrase for that trip was, ‘I’ve seen the American Dream, now I’m going to see the Indian Dream.'” The idea developed. “When I was in Kerala I really noticed that as soon as you transfer an ideology, or even a symbol or a shape from the East to the West, it always transforms when it lands in the West and manifests in a negative way.” This squared with her own experience coming from Sri Lanka to London and her later attempts to rekindle some of the old pop model in a new way. “Yes, when I transferred my story to the West the only way that it could exist was by people being aggro about it.”

She already knew India, having schooled there as an infant and later recorded two of the killer cuts, Bird Flu and Boyz, from her most commercially successful record Kala. Her time in Kerala left more specific emotional imprints. She learnt of the Hindu goddess of music, Matangi, who she shared a first name with, though is wary about talking up this rudimentary Google discovery for fear of appearing to follow an expected pop cliché. This is what happens to pop stars, she reckons: “You either go mad or you become a drug addict or you become spiritual. I’ve gone for all three of them.” She laughs. “Well, I’m not a drug addict but I’ve been branded all of that.”

Despite herself, the compulsion to make a new record began fomenting. Back home in London, she went to a studio in Elephant and Castle and laid down material with only her engineer. Music is the thing that makes M.I.A. happy. When she talks of a trip to the Caribbean chaos of Beckway and what that did to her mind and how that viscerally manifested itself in her music, it is impossible not to be reminded of another artist who enjoyed little in the way of mainstream support, but delivered a set of records between 1979-83 that continue to resound apocalyptically through every nuance of modern pop noise and presentation.

History won’t write M.I.A. out of the picture. Time will likely be kind to her because she has that Grace Jones thing. When Jones found Sly & Robbie and recorded her albums Warm Leatherette, Nightclubbing and Living My Life, she became a pivot on which the possibilities of pop could find a scintillating new angle. Of course different eras require different precedents to be set. Jones harnessed her menace through a sound that beguiled because it was louche and patient. M.I.A’s is crunchy, amorphous and chaotic. But still. It is true to her. “I came up with this theory,” she says. “That you can’t fake it, you have to live it. I live what I put out. There was a reason that I made Maya and as long as I stuck to it and I instinctively stuck to it, I was right.” She thinks about this for a second. “As an artist, that is all you have.”

Credits

Text Paul Flynn

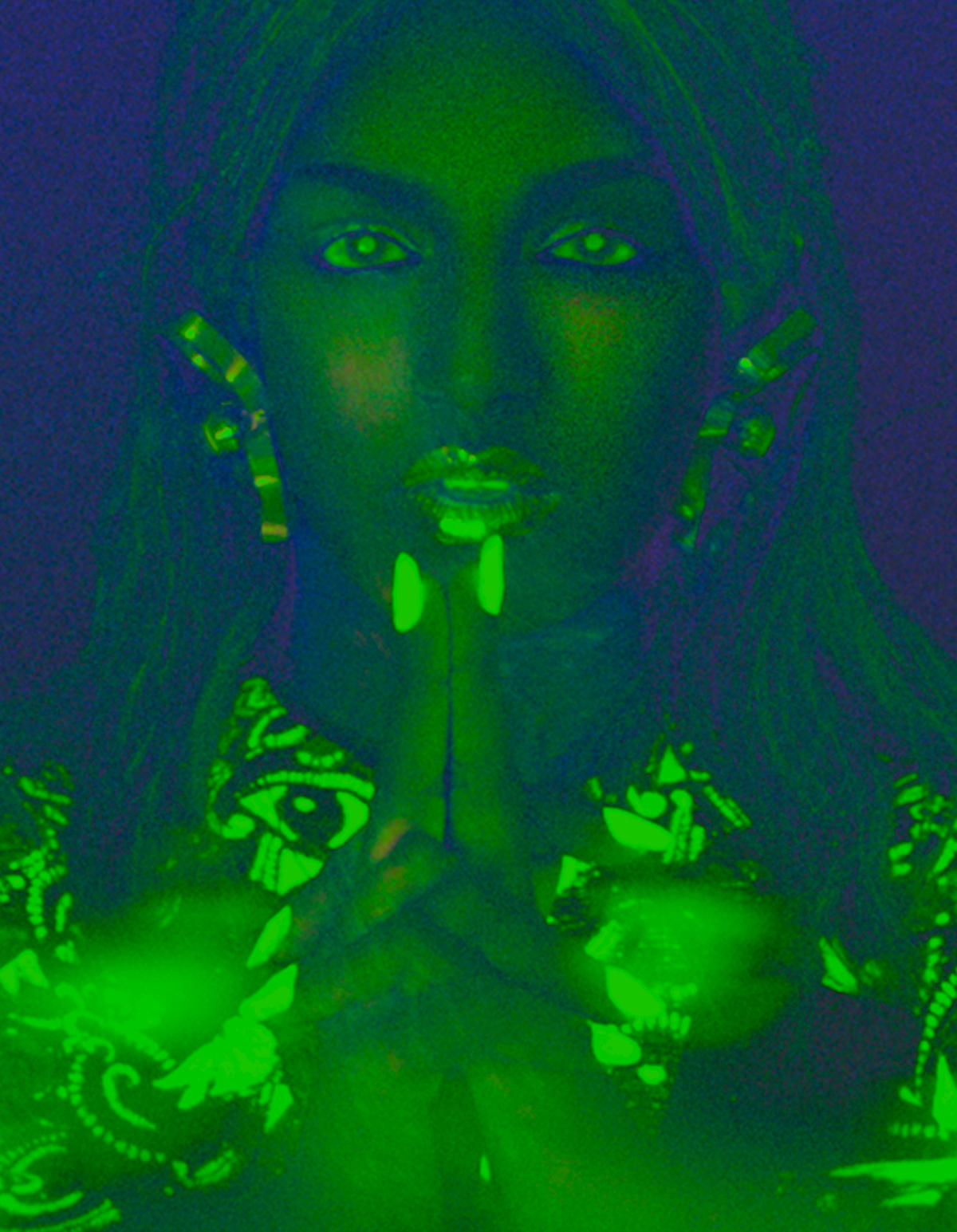

Film stills Daniel Sannwald

Styling Julia Sarr-Jamois

Director of Photography Pau Castejon

Hair Tina Outen at Streeters

Make-up Lucia Pica at Art Partner

Nail technician Zarra Celik at CLM

Styling assistance Rochelle Brady, Bo Houtenbos

Make-up assistance Siobhan Furlong

Special thanks to Somesuch & Co.

M.I.A. wears all clothing and accessories Kenzo.