Haunted houses are big business. They’re especially big business in the US, where around 1,200 haunted houses pop up each year for spooky season, generating an estimated $500 million in ticket sales every year. Some of these attractions are small-scale, mom-and-pop organisations; corn mazes, pop-up attractions at local malls, or even homemade haunted houses in people’s backyards. Others are full-scale operations months in the making, incorporating all the special effects you’d expect to see in a theme park and employing dozens (in some cases hundreds) of professional scare actors.

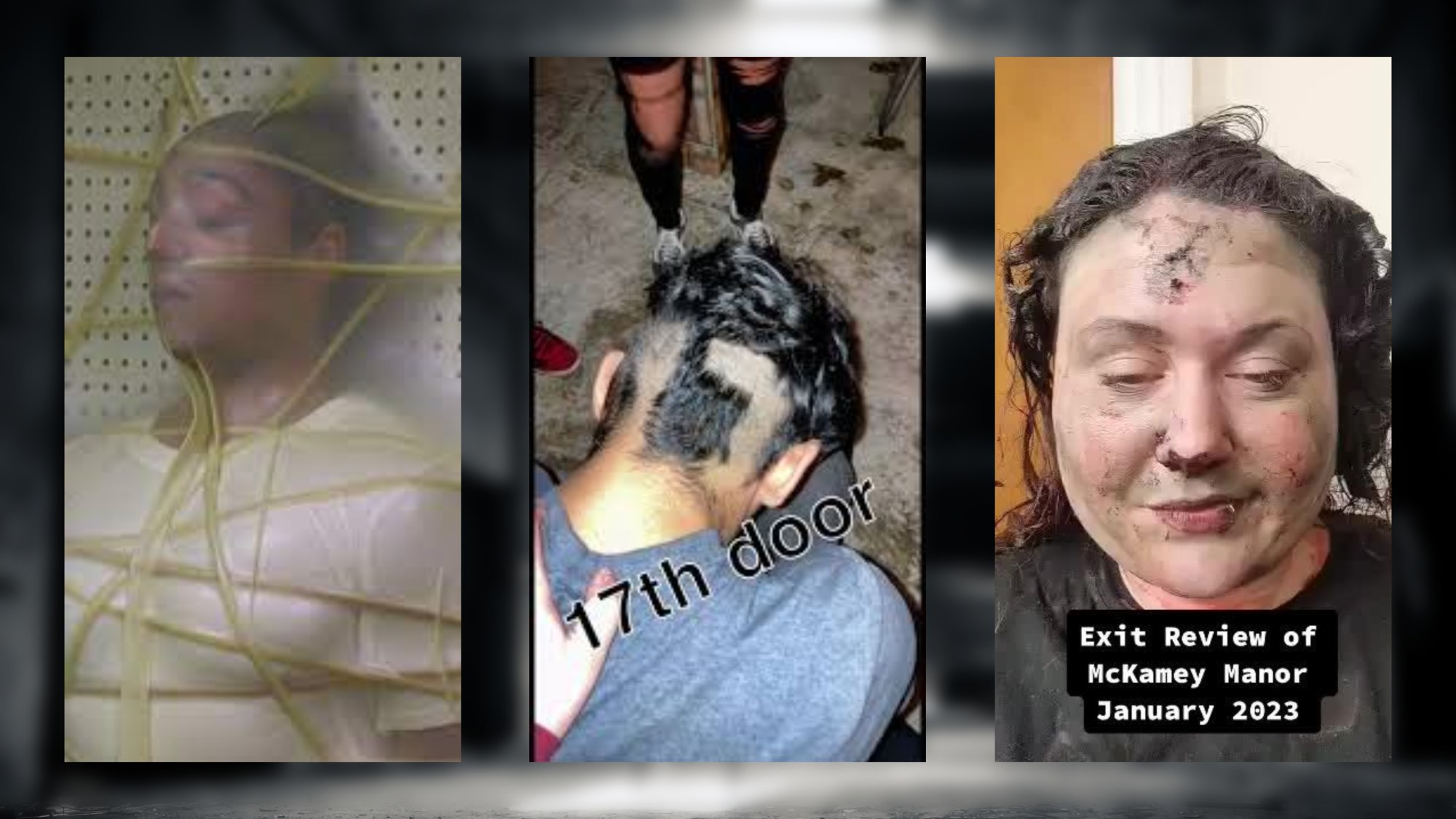

But as business booms, so does competition. The more haunted house attractions there are, the scarier they get to bring in guests, with more and more so-called ‘extreme haunts’ popping up across the US. At probably the most well-publicised haunt attraction in the world, The 17th Door (which even has its own reality TV show on Amazon Prime), guests receive electric shocks and are suctioned into latex, both experiences that seem to be directly borrowed from the world of kink (where these things are known as ‘electro-play’ and ‘breath-play’). Probably the only haunt more famous (or infamous) than The 17th Door is McKamey Manor, the subject of a documentary that came out this month on Hulu. At The 17th Door, and almost all other extreme haunts, there is also a safe word, which will immediately stop all activity if uttered by a guest – another staple of the world of kink.

Sex and Halloween have always gone hand in hand, whether that’s Halloween-themed porn (PornHub’s search trends for Halloween last year showed huge increases in searches for ‘monster’, ‘ghost’ and ‘exorcist’) or the literally hundreds of Halloween costumes suffixed with the word ‘sexy’. And kink steps into the mainstream at Halloween, too; it’s the time when costume shops won’t bat an eyelid at selling bondage gear and gimp suits under the guise of a spooky costume. Haunted houses, kink clubs and dungeons have a lot in common when it comes to aesthetics, too. You might expect to see gimp masks, ropes and chains and handcuffs, red lighting, whips and even tasers.

But haunted house attractions aren’t advertised as sexy; they’re scary. And some are very much mainstream, selling upwards of 30,000 tickets in a season. Why might people be more comfortable exploring elements of kink in the context of a horror experience? “It’s almost like a work-around,” says Gigi Engle, a certified sex therapist specialising in GSRD (gender, sexual, and relationship diversity). “People can convince themselves it’s not sexual because you’re not naked, it’s not explicitly sexual in that sense, and so people can feel they’re exploring this in a way that doesn’t reflect so much on them and the socialised shame we apply to sex.”

Evita “Lavitaloca” Sawyers, polyamory content creator and author of A Polyamory Devotional (a handbook of daily reflections and affirmations for those embracing non-monogamy), agrees, pointing out that distancing these attractions from any outspoken associations with kink is problematic because kink is “respectable on its own.” What’s more, by borrowing from this world, attractions are showcasing a kind of make-believe version of kink and are stepping on the shoulders of those who have done the background work. “It’s kind of like they are showcasing the final product but not showing the work that goes into making a scene happen”, Evita says.

The kind of thrill that people get from intense experiences, whether kinky or scary, can have real psychological benefits. There’s evidence to suggest that anxious people enjoy horror movies, for example, because they provide a helpful way to deal with anxious feelings in a safe environment. Likewise, kink can help people to deal with trauma and to process negative emotions. But these experiences exist on a scale, and the more extreme haunted houses at the end of that scale are extremely controversial.

The most well-known of these is probably McKamey Manor, an infamous attraction that’s edging into the very extreme end of BDSM. Visitors are abducted, force-fed, physically attacked, and even (allegedly) waterboarded. People wanting to experience this haunted house first have to send a video application to owner and creator Russ McKamey, who seems to be mimicking the language of a dom/sub dynamic in an email that potential visitors receive, which reads: “[…] do you want the Big boy tour, or the Sissy baby tour. If you want the baby tour, you’ll need to beg and plead for that on video. […] The bottom line is that you need to impress me.”

Although the attraction co-opts the language of kink, it pushes it into extremely dark territory; a Change.org petition to shut down McKamey manor has almost 200,000 signatures. Disturbingly, the parameters of consent are murky; there is no safe word at McKamey, and guests must sign a 40-page waiver before entering. Former guests posting on TikTok have called Russ a “psychopath” and his haunted house “sick in the head and twisted”, while others claim it’s all a big scam. Perhaps most tellingly, other haunt creators and professional scare actors came out to actively criticise McKamey Manor in indie documentary Haunters: The Art of the Scare, saying in particular that it isn’t acceptable to run a haunt without a safe word.

Karl, who runs one of London’s most well-known kink club nights, Klub Verboten, says he’s always been uncomfortable with the way kink and Halloween are conflated, pointing out that this often contributes to a harmful narrative where kinksters are branded as dangerous. “Norman Bates was not a kinkster, and neither were his real-life equivalents,” Karl says. “Sadly, a very common misconception is to perceive kink practices such as BDSM as violence. Undoubtedly, some practitioners play on the very fringes of the human body’s capabilities, but that always comes with great responsibility, consent and care. If there’s one thing, the kink community upholds its consent and care for one another. Without these, you’re left with sexual assault and nothing less.”

So, how can extreme haunted house attractions make sure they’re following proper consent practices? “A great way to protect consumers, and staff too, would be to have kinksters come in and teach staff how to really understand and use consent,” Gigi says. “They probably won’t do that, though, because they don’t want to be too directly associated with sex or kink. But if these attractions were able to embrace the ways they are similar, I think they’d be able to benefit a lot from that.”

For the time being, though, it seems that haunted houses are still contributing to a narrative that has long frustrated sex-positive educators and kinksters alike: that kinky equals scary.