“I always had a hunger to be outside on beautiful days,” native New Yorker Stanley Stellar recalls. “When I was in school, all I would do is look out the window and think, ‘How much more do I have to sit in this classroom? I want freedom!’”

Independence, self-determination and creativity have played an integral part in Stanley’s life. Coming of age in Brooklyn during the 1950s and 60s, Stanley remembers how it felt to be a young, gay boy in a profoundly homophobic world. Castigated and vilified, queer men lived under the constant threat of being disowned, arrested, denied employment, housing, education and healthcare until 2003 when the United States Supreme Court finally struck down all laws criminalising homosexuality.

During his formative years, Stanley remembers rarely seeing images of gay men, and what little there were cast them in a derogatory light while fanning the flames of fear, shame and bigotry. “When they showed us in the media, it was as hustlers on 42nd Street,” he says. “I used to think about why they chose only to see us this way, considering there are so many creative gay people in the arts. Why were we represented in such a shabby, ugly way all the time?”

Seeking solace, Stanley found comfort in the glossy pages of magazines, which offered a glamorous vision of life. Inspired by the work of photographers like Diane Arbus and Richard Avedon, Stanley understood artists had the power to change how we looked at the world. He also realised that although museums refused to recognise the LGBTQ+ community, they have always played an integral role in art history. “That was our secret because there was never any mention of our existence.”

Driven by his passion, Stanley studied graphic design at Parsons before launching his career as art director of Art Direction. “It was the Mad Men era for advertising agencies,” says Stanley. “I felt very cool because I was meeting photographers from around the world and actually making money for the first time.”

By the early 70s, Stanley had discovered the flourishing gay scene in Manhattan’s West Village, which had become a safe haven for the queer community in the years following the Stonewall Uprising. In the evenings, Stanley would meet up with friends and hang outside the fabled Women’s House of Detention, a fortress-like jail that stood on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Greenwich Avenue. Eventually, the police would come, accuse them of loitering, and demand they disperse.

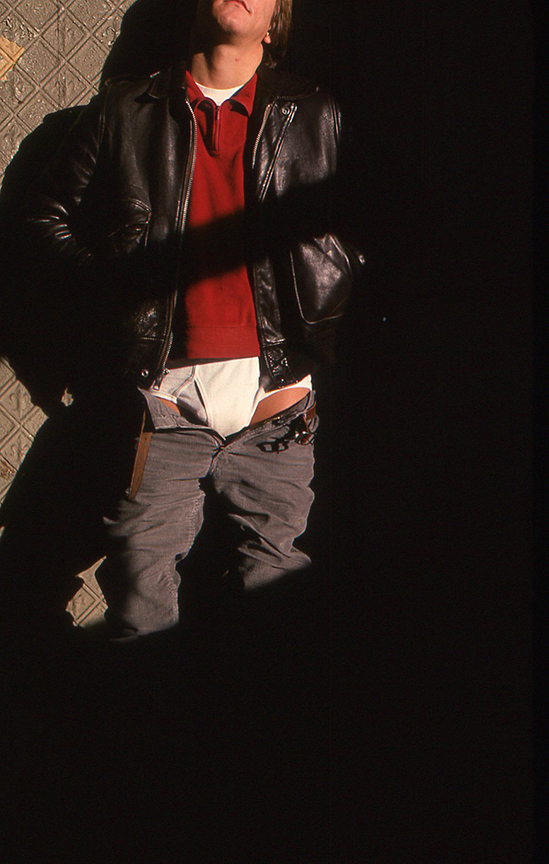

Driven further west, Stellar came upon Christopher Street — the heart and soul of New York‘s creative and queer scene. Leading from Seventh Avenue South to the Hudson River, the seven-block street was the perfect escape from the claustrophobic strictures of the cis-heterosexual world. “It was dark, full of broken glass and rubble, illegally parked cars and abandoned trucks,” Stanley says. “It was a place I belonged and was safe. I knew every inch of every block. Christopher Street was mine.”

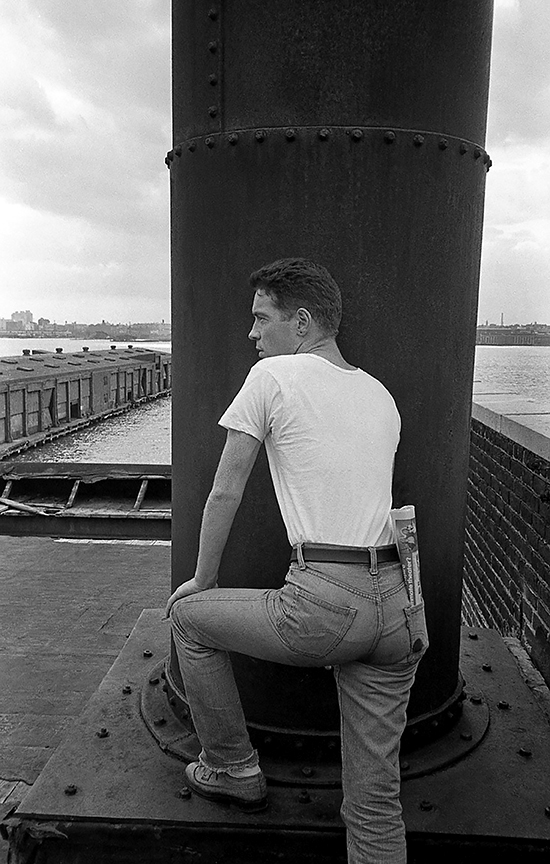

In 1976, he purchased his first professional camera and hit the streets, photographing the world he knew best. On one particularly seismic day, he followed a group of men heading past the seedy leather bars that stood at the far end of Christopher Street and making their way under the abandoned remains of the elevated West Side Highway. Climbing across the concrete dividers that stood between car lanes, Stanley discovered a new world that would become a constant place of documentation in his work: the Christopher Street Pier.

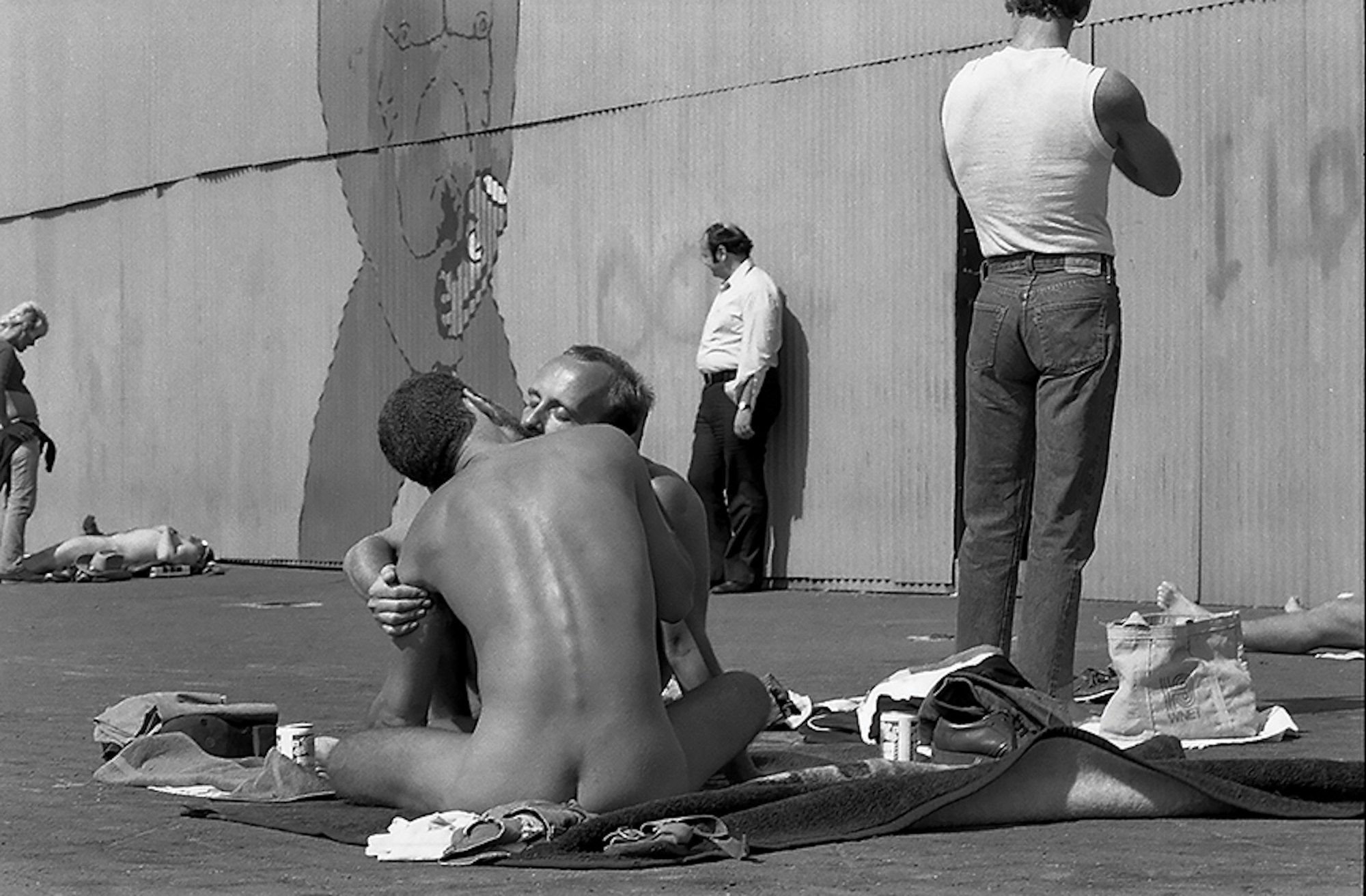

A massive, abandoned warehouse stood on a concrete slab that jutted out on the furthest edge of the city into the Hudson River. Stanley passed through a hole in the wooden fence and suddenly found himself inside a secret world habituated solely by queer men. Here in broad daylight, one could freely partake in the pleasures of socialising, nude sunbathing and cruising for trade. With the economic collapse of New York, a feeling of anarchy reigned supreme as the dilapidated buildings became the perfect setting for fearless libertines. For one brief, shining moment between the Stonewall Uprising and AIDS, the piers on the west side became the ideal destination for men seeking anonymous encounters any hour of the day or night.

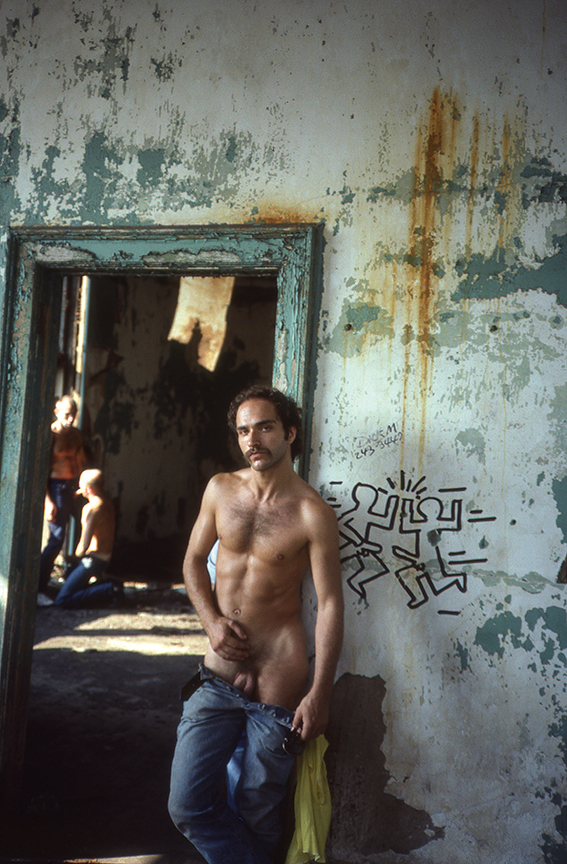

“It was like a wonderland. [The building] was a gigantic, empty space that was no longer in use. It was like a stage set. You could go up staircases to the second floor, which had offices for the workers, or go across the catwalk. Everything was painted aqua green and peeling. There were corners and closets where we could discreetly hang out or blatantly look like you wanted to have sex,” Stanley says.

“Everyone followed unspoken rules. You could lean against the window in the sunlight and watch other boys walk through the rooms, looking at each other, and if a connection was made they might approach you. Or you could stand at a distance and watch. People respected each other’s space. I remember always seeing one guy who lived in the East Village arrive mid-afternoon with a brown paper bag filled with cucumbers and carrots. He would go in the corner and — well, you get the idea.”

Surrounded by this extraordinary outpouring of freedom, Stanley felt at ease approaching strangers, chatting them up, and offering to collaborate on photographs, which will be on view in The Piers, opening 15 January at Kapp Kapp in New York. “It was an incredible place,” Stanley adds. “I would meet guys there who were incredible looking. The piers were my studio and my oasis. It was the natural evolution of my work as a street photographer.” The piers were not only a cruising haven; it was an artist outpost, attracting the likes of Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz and Alvin Baltrop, who also found inspiration in the scene.

Stanley, who was living in Tribeca, could easily walk up to the piers from his home, and spend the day outdoors. “I never left the house without my camera and film,” he says. “We would lie on a big slab of cement in the sun. Being a young gay artist, you could be there on a Thursday afternoon at four o’clock, bring a bottle of seltzer or beer, a transistor radio and hang out with your friends. The Circle Line would cruise around Manhattan. We’d wave to them, and they’d wave back. It was our world.”

‘Stanley Stellar: The Piers‘ is on view at Kapp Kapp in New York from 15 January

Credits

All images courtesy Stanley Stellar