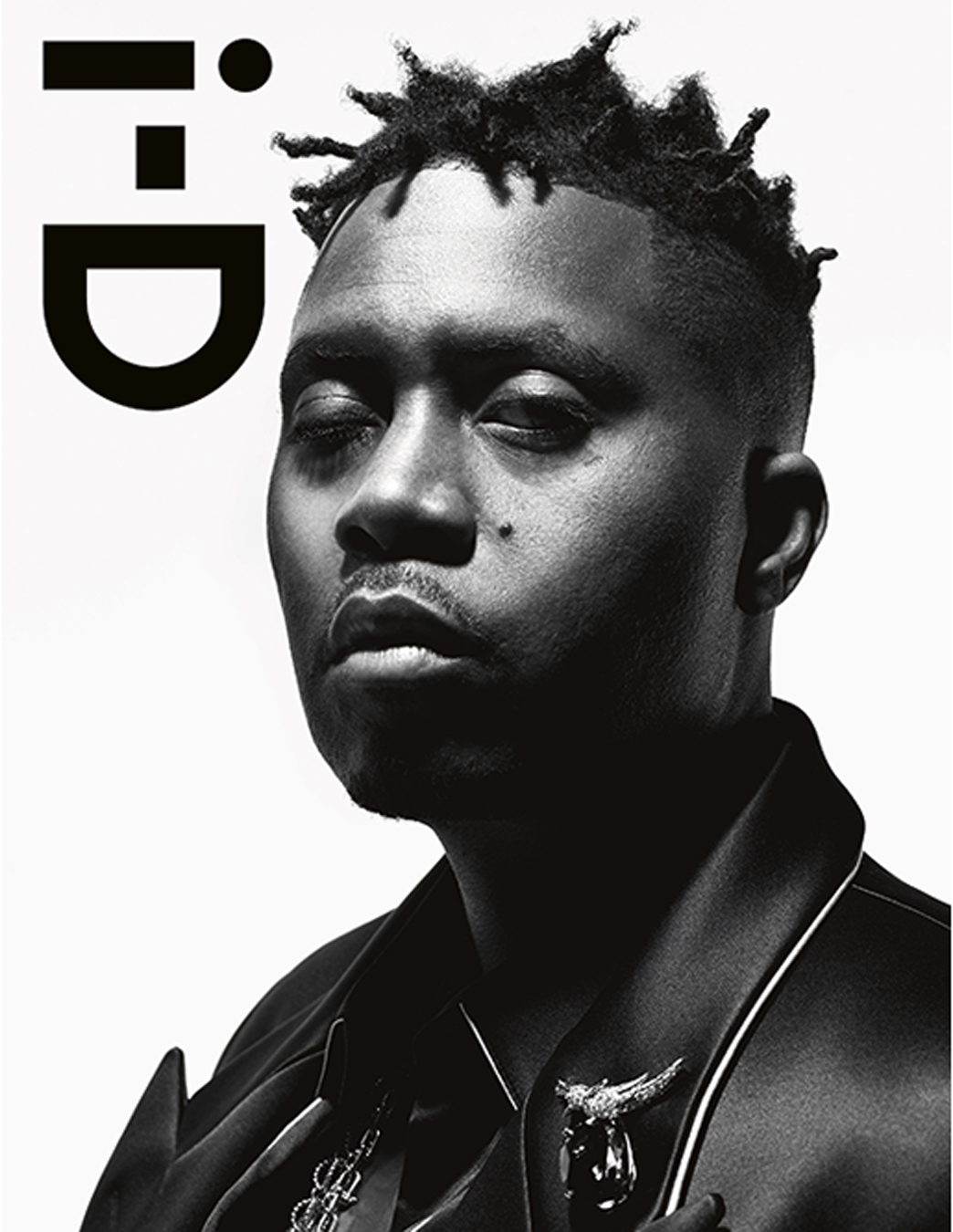

This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Out Of The Blue issue, no. 366, Winter 2021. With thanks to Tiffany & Co. Order your copy here.

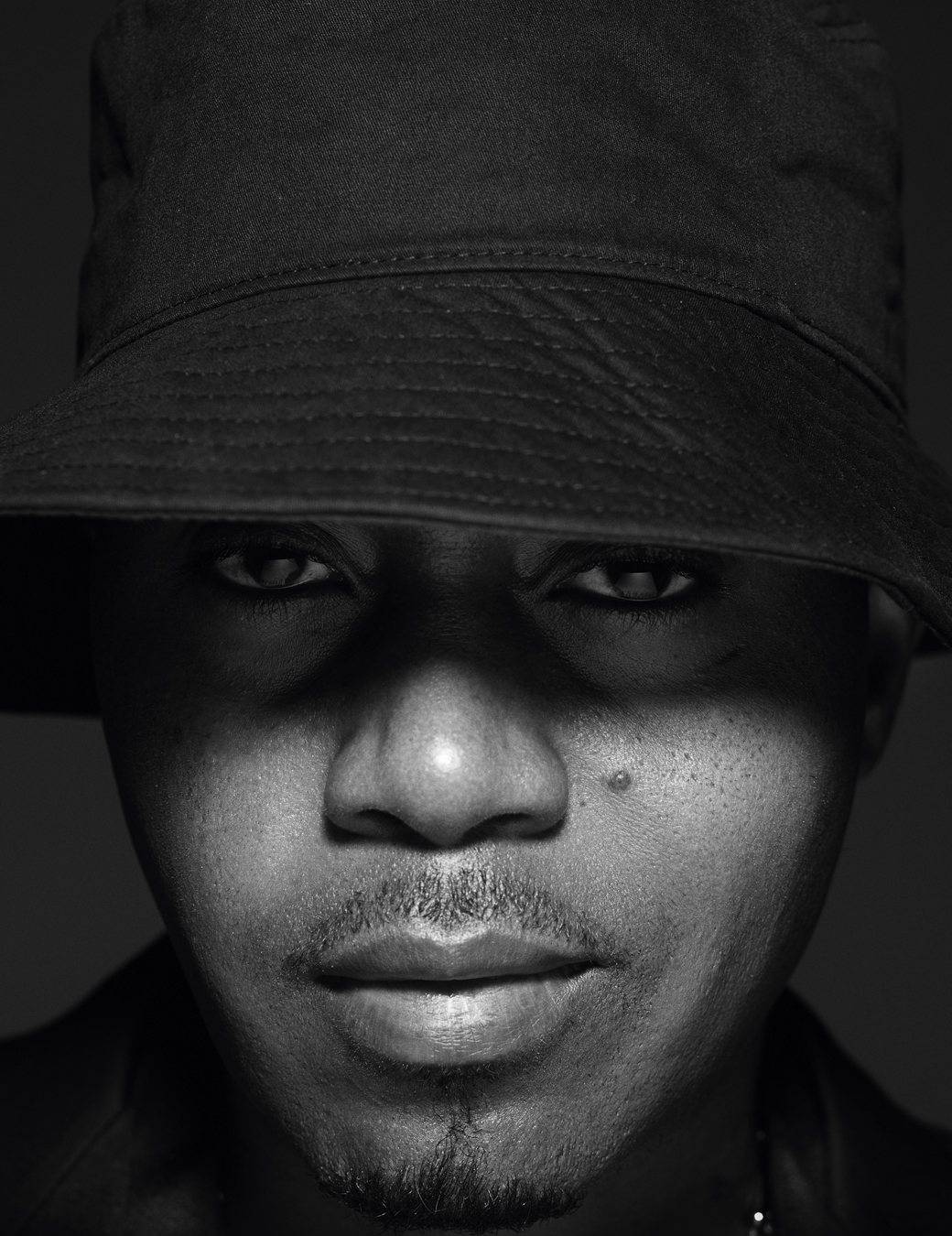

Nas has the kind of voice that lingers in your mind long after you hear it. There’s a smooth warmth underneath its gravelly edge. That voice, and how Nas uses it, has been at the core of what many of us hold dearly about hip-hop. Since his emergence as a baby-faced teenager in the halcyon days of hip-hop’s golden age, Nas has captivated us with his poetic storytelling, and a visceral flow that has given us an immersive look into the world the way he lives and sees it. I first interviewed Nas nearly a decade ago. We sat down to talk about his landmark 10th album Life Is Good. He was approaching forty then, and our conversation often drifted towards the idea of legacy and what he wanted his to be – understandable, considering he was now a father of two and growing older in an industry driven by youth.

When we reconnected earlier this fall, the man born Nasir Bin Olu Dara Jones was in the midst of yet another momentous time in his life. In just the last year the Library of Congress inducted his debut album – the impeccable and revolutionary classic Illmatic – into the National Recording Registry, he won his first Grammy (after a quarter-century of snubs) for King’s Disease, and followed that album up with a critically acclaimed sequel.

Nas is approaching fifty now. He’s just about as old as the genre his voice helped define, which places the Queensbridge legend in an even more rarefied space as one of the few MC’s that were around to help build contemporary hip-hop. He ushered it towards the superpower it is today while maintaining his relevancy.

Before we talked, I looked back on that old interview, to see if it would spark some inspiration for the direction of this conversation. The idea of legacy stood out. He’d been in search of establishing his legacy when we last spoke, and I wanted to know what that looked like for him as he approached his next decade.

Gerrick: We don’t often see the type of longevity in hip-hop that you’ve had. How do you define success? Has your idea of it shifted any over the last decade?

Nas: A little bit, here and there. As you experience different things in life, life seems to get better for you – it can seem to get easier down the road. And that, to me, is a form of peace and happiness, and that to me is what success is supposed to bring.

Gerrick: Kings Disease II really felt like an album where you’re intentionally focused on your legacy as a rapper – while also celebrating yourself in a particular kind of way.

Nas: I love that. I think it should give people some insight into where I’ve been and where I’m going. But also at the same time, just expressing what I’m feeling, how my day is, and where I’m at in my age these days, and how happy I was to just get in a comfort zone and make music. And at this place where I’m at in my life, I’m happy to give people that experience.

Gerrick: I think about a track like Death Row East on this new album. What you did there, has almost a sense of survivor’s guilt throughout the album.

Nas: Survivor’s guilt is interesting. The longer you stay around, the more of a target you become. That’s the danger of staying around. You don’t

want to be the one hit wonder, you don’t want to have a short career, but if you do have a long career, then you are a target for so many people. With the Death Row East story, there’s so many people that talk about having beef with Suge Knight, because he’s just this imposing figure in the game. Death Row was the most powerful label in 1996, so any story about running into Suge Knight is a dope, because Suge is a super famous street legend in the music industry. We’d never seen nothing like it then, but my story is about the real Death Row interaction in New York. That’s why I thought it was important to tell that story, because that’s the real story of the era of the 90s, and stuff that kind of built the path for people to walk on now.

Gerrick: That record really feels like the centrepiece of the album.

Nas: I knew it would stand out. It was the first song that I worked on when I started making the album. I knew people would talk about it, but it was important because there were a lot of stories that weren’t one hundred percent true about what happened. There were a lot of stories out there about this part of my life, so why would I not clarify the thing that people have been talking about, when they’re talking about me?

Gerrick: When you were a teenager working on Illmatic, did any part of you hope or believe that hip-hop would become the superpower it is now? Did you allow yourself to dream that big then?

Nas: Even before I got to the game, I always thought I couldn’t wait for Run DMC and Adidas to really get together and smash it. I couldn’t wait for Slick Rick and the Bally brand to get together and smash it. I couldn’t wait for hip-hop music to play on daytime radio all day, like it’s playing now. So yeah, I always wanted to see it go all the way. As far as my contributions? I just wanted to represent. I didn’t know how far it would go – I just wanted to represent and get in the game.

“The longer you stay around, the more of a target you become.”

Gerrick: On the flip side of that though, did it frustrate you to see how our community judged young Black boys for looking at rap, or playing ball as a path to success?

Nas: I grimace at the country for there not being enough inclusion when I was coming up. There were only these two things – rapping and basketball – but we had so much to offer, and we did so much through the years in this great country because we have made such huge contributions. They haven’t put spotlights on all these great things that we’ve developed in this country, invented, and helped create. But there are a lot of spotlights when you’re on stage, and when you’re on the basketball court and that is what I grimace at.

Gerrick: Before KD I and KD II you did NASIR with Ye. That was your first release in about six years – the longest break you had taken from music. What did you learn about yourself at that time?

Nas: About myself? That I’m just getting started. I haven’t done it all yet and I have so much ahead of me. I realised that I am my own movement. And I don’t just talk it, I’m walking it. I want to be something that people can see and know, “Hey, I can do that too.”

Gerrick: Did you feel a kind of way about the reception Nasir got?

Nas: Well, I was excited to do it because I wanted to show how it should be done, without sounding cocky. It does sound cocky, fuck it, it is what it is. I wanted to show how it can be done. I can’t just make records for people, just because they want to make records, or it won’t come out right. Then everybody looks bad. I have to feel it. I have to be moved to do shit. And that’s just what it is. I’m happy that I was able to stay in my bag and get that feeling again.

Gerrick: What was the calling you felt to connect with Hit-Boy?

Nas: I was just trying to record music. It just so happened that the world stopped just as we started doing the two songs. He kept on at me to come up to the studio and work, and he pushed me to make it work. I was already

a fan of his work, so I knew if we got in a room we would do something cool. I knew there would be great shit, but I didn’t know if that would be one song, two songs, or five songs. I definitely didn’t know it would be an album.

Gerrick: It’s got to feel good to have this level of acclaim back to back.

Nas: It’s the best feeling to know that other people share the same feeling we have towards the music. With KD I, we owed that to ourselves; we owed that record to the listeners, we owed that to the people going through these tough times. So we knew what it was, and we sure felt like we knew what it was.

Gerrick: What was that moment of getting that Grammy like for you?

Nas: Oh man, it was a couple of things. I almost felt like I was abandoning all the artists that I was with who had never received any awards. And that’s a cool club to be in. I take pride in being in that no-award, no-Grammy award club. I was honoured. But I believe Pac would’ve got one. B.I.G. would’ve got one. But they’re bigger than awards, those guys. So I feel like this is a great story to see someone who said, “Damn, that guy at his peak should’ve won this, that and the other.” And then boom, here he comes out of nowhere with some shit you wasn’t even knowing was coming, and it’s at a crazy time in the world, a historic time. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been around, it doesn’t matter what people think or thought, do what you’re doing, keep doing what you’re doing, and somebody’s going to recognise it. It doesn’t always have to be an award show, but the universe recognises it. And that works for me.

Gerrick: How did the decision to do a sequel come together?

Nas: We worked pretty fast. In the middle of KD I, we both just looked and said, “Yo, we got to do another album.” We weren’t even finished with the first one. And we said we got to do another album, because that’s just what we were feeling. That was the momentum in the room.

Gerrick: Do you feel any pressure to keep up with the pace rap currently moves in? I mean two albums in a year certainly gives that impression.

Nas: Not at all. It happened because it happened. Like to drop two albums in a year, that was just the electricity in it, you know what I mean? That’s just how the energy was for me and Hit-Boy. So I mean, if anything I’m slowing it down a bit, maybe.

Gerrick: Maybe?

Nas: It’s not like I want the attention, I just love doing it. I don’t want too many eyeballs on me all the time, so I live in between that. The music will speak for itself. The music will do what it’s going to do. People will feel it, or they won’t. Or maybe they’ll feel it five years later, or maybe they’ll never feel it.

Gerrick: Your music has always been cathartic, but what do you do when it wakes something up in you? Do you sit with a therapist, or do you just go and make another record?

Nas: I don’t see a therapist. That’s on my to-do list, and it has been on my to-do list for the past two years. A lot of friends of mine do and they love it. I plan to do that. I also thought I could do that with a girlfriend – maybe I could do that – but that’s not fair to them. So maybe one of these days. The music does help me. I probably don’t need a therapist because I have music, but that’s not so true.

Gerrick: If you were given the chance to redo any album of yours, would you take it? And which one would you redo?

Nas: No, but if I decided to challenge myself to do it, I would probably change some things on I Am… and I would change some things probably on Nastradamus. I don’t even know what’s on those albums. I could probably only remember two songs for each album.

Gerrick: I want to end here. I started by asking you your idea of success and how that has shifted. What about happiness? What does happiness look like for you, and has that shifted any in the last ten years?

Nas: I’m trying not to feel bad about being happy. The world will try to steal that from you, or make you feel bad or wrong to have a good day. There’s so much I want to help, and when you get to a place where you can help you want to do more. And sometimes I want to feel like it’s okay to go on vacation. Or it’s okay to party. And trust me, I fight through it because I am happy. But I can’t be happy until everybody’s happy. That’s how I feel sometimes. Maybe I internalise other people’s pain too much?

Credits

With thanks to Tiffany & Co.

Text Gerrick Kennedy

Photography Mario Sorrenti

Fashion Alastair McKimm

Grooming Chaz Hazlitt using Babyliss Xotics Sweet Jamila and Blue Water

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Chanel

Photography assistance Kotaro Kawashima and Brett Ross

Digital technician Chad Meyer

Fashion assistance Madison Matusich, Milton Dixon III, Jermaine Daley and Casey Conrad

Tailor Martin Keehn

Production Katie Fash, Layla Néméjanki and Steve Sutton

Production assistance William Cipos

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING

All jewellery (worn throughout) Tiffany & Co.