Since I was diagnosed with HIV five years ago, I have been part of a new wave of activists trying to update the record on what it means to live well with a virus once synonymous with death. The diagnosis also shaped my research as an academic, where I have challenged the notion that positive people are “reckless” in both the criminal law and news media. Recently, I interviewed 20 people living with HIV about their experiences during COVID-19, building on community expertise in public health messaging and mental health resilience. Some of their experiences are shared here, too (their names have been changed to protect participant anonymity).

At the advent of the crisis, government information campaigns left a lasting impression on the public’s consciousness of HIV, from the infamous tombstone and iceberg adverts to the leaflet sent to every household in the country with a warning: ‘There is no cure. And it kills.’ “The images in the 80s and the 90s were horrific,” a woman named Mary, who was diagnosed at this time, tells me. “I guess it’s self-preservation, or possibly denial; I didn’t want to look at them. It’s very doom-mongering, especially if you’ve received a diagnosis because they are effectively telling you. ‘If you are diagnosed today, you will be dead tomorrow.'”

Similarly, Larissa was around 17 or 18 when the Don’t Die of Ignorance campaigns began. “It was very much doom and gloom,” she added. “I think my overwhelming message from it was, ‘If you get it, you’ll die’, but thinking, ‘Well, it’s not really aimed at someone like me, so I’m not gonna really worry about it’.” The impact of AIDS on already marginalised groups meant the virus itself became associated with existing social stigma and sexual shame. As I have noted elsewhere, “The conflation of HIV with death and homosexuality contributed to the most homophobic period ever recorded by social surveys. At this time, Thatcher’s government enacted Section 28 to prohibit the promotion of homosexuality”.

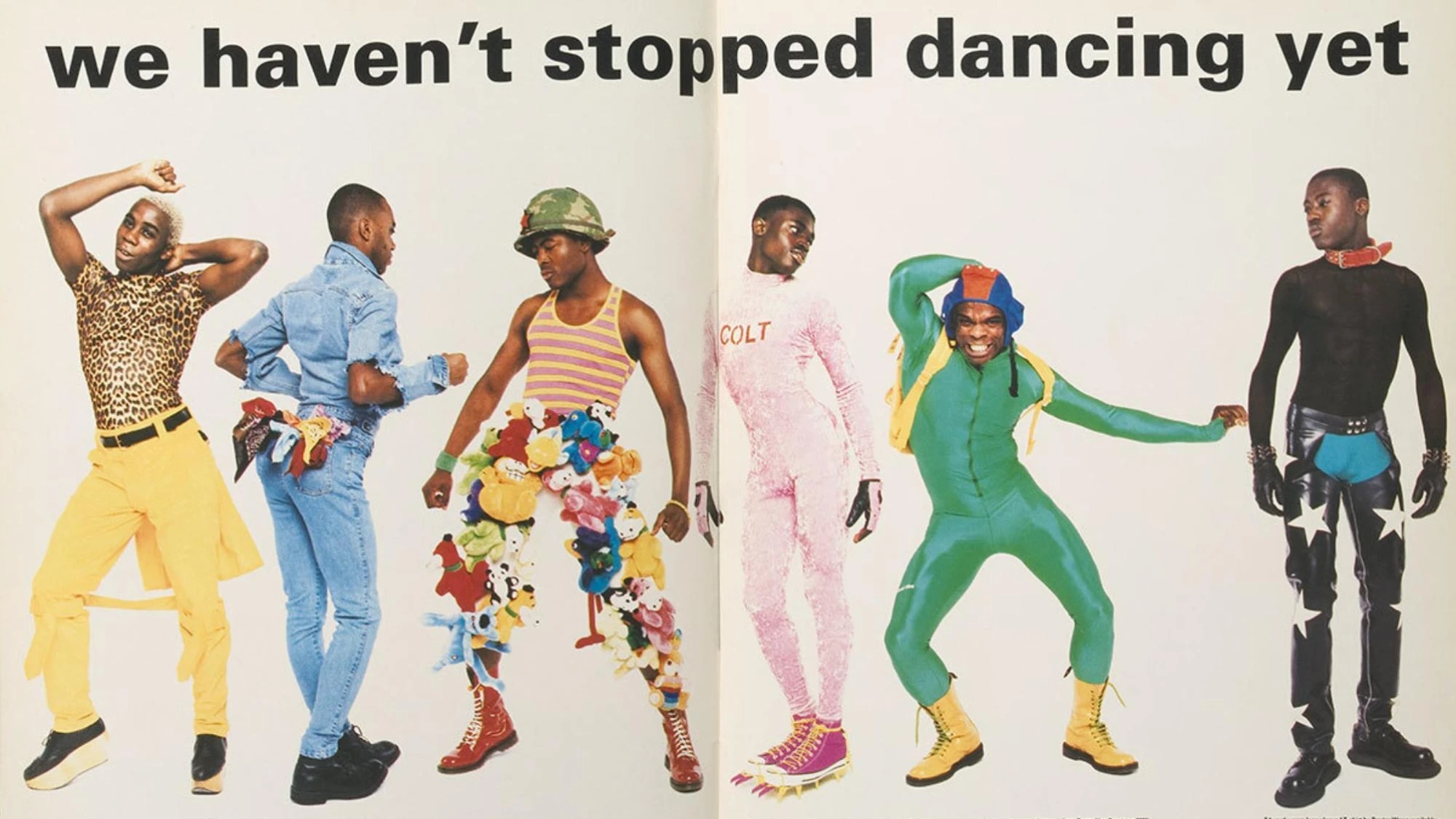

In response, queer activists — often working in groups such as ACT UP and OutRage! — staged performance protests — die-ins and kiss-ins — to shock a complacent and homophobic government into action. The former is still active in many cities around the world, with a focus on changing attitudes towards HIV and increasing visibility surrounding those living with it.

As we know, things changed in 1996 with the emergence of highly effective medications, which transformed HIV from a deadly diagnosis to a chronic condition. Today, most of us take one pill a day to suppress the virus. Soon, injectable medications will be available, reducing the number of treatments needed to just six a year. These medications are so safe and effective that anyone diagnosed today has an average life expectancy and cannot pass the virus on, while HIV negative people can take them as a prevention method in the form of PrEP.

The National AIDS Trust spent years challenging NHS England through the courts to make PrEP free on the NHS. “These advances, and others like them, have made the landscape for people living with HIV quite different today than it was a decade ago,” the charity’s Chief Executive, Deborah Gold, says. “We now know, beyond all certainty, that people on effective treatment cannot pass the virus on, but too many people remain unaware of this fact. The science is there, but public opinion has yet to catch up.” As a participant in the PARTNER study, which demonstrated the scientific fact of U=U (undetectable equals untransmissible), much of my activism has centred around sharing this kind of information with audiences who may otherwise be unaware of it.

Many people living with HIV become accidental activists after talking about their status on social media. A month after my diagnosis in September 2016, I shared an image of my medications on Instagram. The caption read: “These drugs have few side effects (hopefully none), and in 2 to 6 months my viral load will be undetectable, meaning I cannot pass it on’. If NHS England had decided to fund PrEP (a daily tablet much like mine) I would not be in this situation.”

Friends and strangers responded to me, almost entirely positively: “Your posts about your HIV status and your discourse on Twitter have challenged my internalised stigma and adjusted my views on [the virus],” one read. Another said: “You’ve already reduced the stigma with me, so job well done. My flatmate works for the National AIDS Trust… as she puts it, HIV is now an inconvenience and not much more.”

For its many flaws, social media has given a greater voice and visibility to many people who are living with HIV. Similarly, Jay Hawkridge became well recognised on TikTok for sharing short video clips talking about the changing reality of the virus. At the premiere of Positive, a documentary about HIV today that will be broadcast by Sky Documentaries, he told me: “It became something that I just started talking about [in real life], because everyone was reacting so well to it. It got to the point where I felt like I’d hit a wall, and try as I might, I couldn’t really go further with it. So a few of my mates were like, ‘Get TikTok‘.”

A point Jay has often repeated on TikTok and Instagram is that, given U=U, the only guarantee you have for avoiding HIV is to have sex with people living with HIV and who have an undetectable viral load; who know their status and have access to treatment. Anyone otherwise who claims to be HIV negative only has their latest test result to rely on.

One of the younger people I interviewed was Ben. “One of the ways I came to terms with my status was watching YouTube videos of people who had been diagnosed and seeing how they were doing, and I didn’t really see anyone who was my age, or who was young,” he said. After posting about his HIV on Twitter and Facebook, “it got thousands of views within the first two weeks. I get Snapchat memories on my phone of that time, and it’s like, ‘You’ve just hit 5,000 views!’”

In the age of digital intimacy, those of us living with HIV have a new and yet familiar set of problems. From routine rejection on dating apps to deciding when or whether to disclose to sexual partners, even in queer online spaces, misinformation about HIV continues to contour our fears and desires. For example, despite meeting his boyfriend on Tinder, a man called Juan said to me, “I mistrust guys on Grindr”.

But from my conversations with other young people living with HIV — including under-represented groups such as migrants, women, trans and non-binary people — there is a sense that the face of HIV activism is changing rapidly alongside the medical leaps and bounds. I asked two people who were born with HIV in 1999 about what kind of images they would like to see representing us in the media. “Happier ones,” Leah tells me. “[But also] ones that show the effect of stigma. I think images of HIV often show the effects of HIV rather than the effects of stigma. I’d love to see that framed as the problem. But also images that show how far we’ve come, what’s important and what’s at stake.”

“I’d love a U=U campaign on TV. I think that would be great,” a young man called Jasper told me. “This is what HIV is like, it’s not a death sentence, and I’m living healthy. I just think we need more representation in HIV so badly, and we do need a TV advert that has the same [effect] as the tombstone.”

In the history of the HIV movement, nothing has been handed to us. We’ve had to fight for better treatment and better representation. As Deborah Gold puts it: “A new generation is defining what HIV activism means to them, and using new avenues, such as social media, to fight stigma.” Social media has allowed for a more diverse range of positive voices to be heard than ever before, but we still need more allies, organisations, and governments to step up and play their part to change the record properly.