This story originally appeared in i-D’s The Darker Issue, no. 365, Winter 2021. Order your copy here.

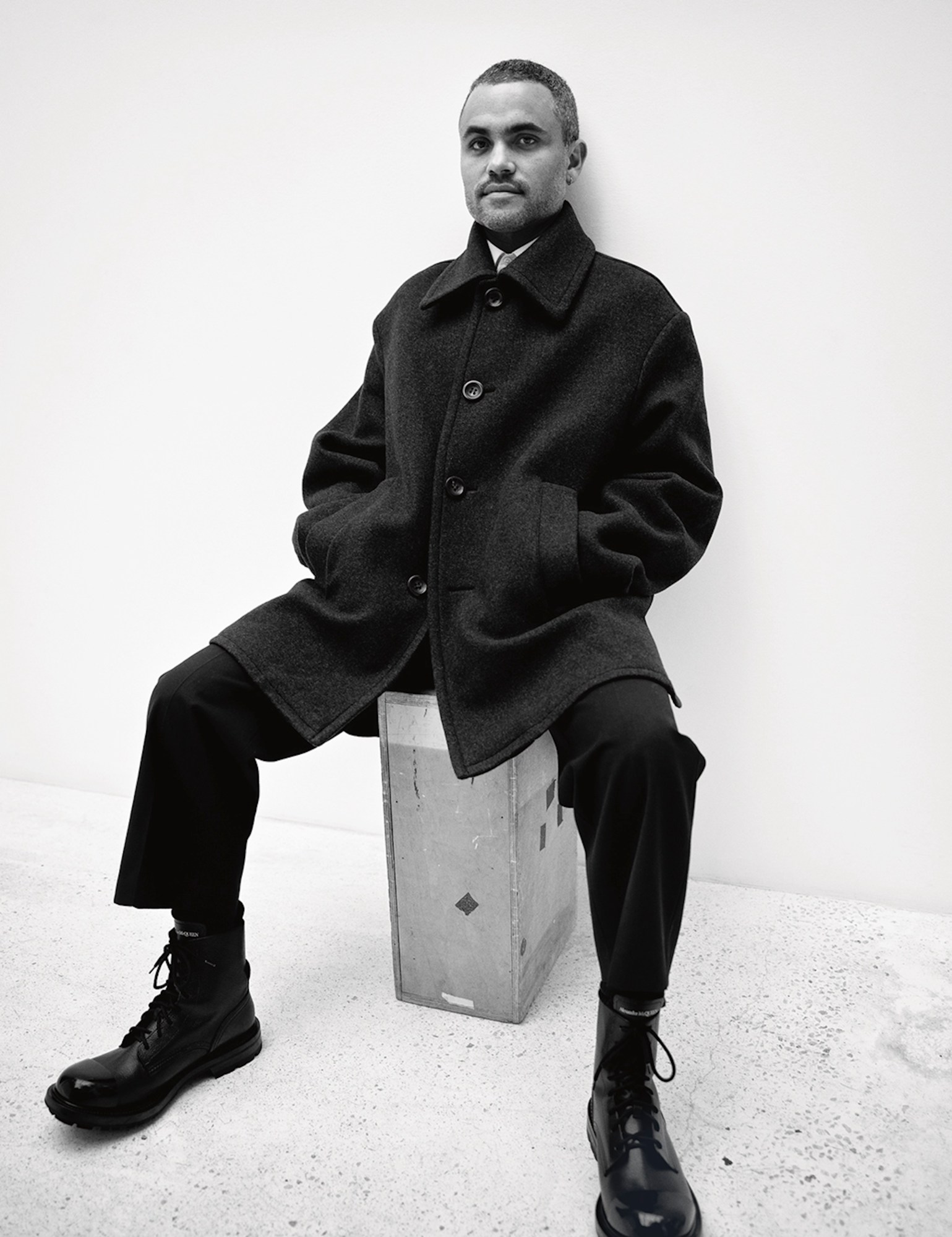

Thomas Lax is Curator of Media and Performance at the Museum of Modern Art. He is currently preparing the exhibition Just Above Midtown: 1974 to the Present. Previously, he worked at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In 2015, Lax was awarded the Walter Hopps Award for Curatorial Achievement, and was a 2017 Center for Curatorial Leadership Fellow.

Would you mind starting off by introducing yourself?

I’m Thomas. I’m currently in Lower Manhattan, which is the place I call home. I got to spend some of my Friday afternoon looking at art.

Whose work did you see?

I had a chance to go see a Burle Marx textile show based around this farm that he had in Brazil. It was really enjoyable. Right now I’m going, to a show that just opened at Orchid Art by Joey Terrill, who was pretty active in the 80s and 90s in Los Angeles.

Have you been spending a lot of time absorbing art in person lately? It seems like things are opening up again in New York.

To me, everything feels in flux. I think the world has felt transitional for quite some time. I feel like like even the world as a concept is up for grabs in a very foundational, generalised, shared way. I live in transition though, so it feels, in some ways, comfortable, but there’s also something quite anxiety- producing about just how unknowable our time is.

Is transition something that’s comfortable for you?

I gravitate towards doorways and hallways and thresholds. There are so many different kinds of architectures where the artists that have given me a vision of the world continue to find themselves. Right now I’m by the water, by the Hudson River. There are these waterways, or pathways where I, having grown up here in New York City, continue to find new ways of staying. Where you find folks, or find yourself as you’re embarking on the necessary work of transformation or self-making.

I know you’re working on a show with Linda Goode Bryant around her gallery, Just Around Midtown, and what you’re saying about space and the work is making me think of how that space functioned for so many black artists. I would love to hear a more about that collaboration as well, especially in our time that is very in flux. But I think sometimes these spaces can bring out new ideas or ways of approaching work.

Just Above Midtown was started in 1974 in the wake of another moment of crisis, against another set of public institutions that were meant to metabolise crisis but that were not up to the task. Then, as now, people were looking to museums to be cultural spaces that could offer a kind of respite, or commons, in which people could reformulate their relationship to one another in a moment of total transformation.

As the realities of environmental catastrophe and social inequality that produced both the Covid pandemic and last summer’s uprising become the stuff that we can describe as art stuff, as we have more descriptive schools to name how art is made from their material, I think JAM and other types of para-institutional projects can hold a space for rehearsal or practice to draft the kinds of responses or relations that can come up in the wake of total upheavals.

When I first encountered Linda Goode Bryant’s work I was amazed by the scale of what she was doing, everything from JAM to Project EATS. The range of possibilities that she’s actually activated and created feels beautiful and also very New York in a particular way.

I love what you said about the scale of it and the New York-ness of it, because it is at once miniature and grand. JAM, when it opened, was a 724 square foot space but also imagined itself as a whole world unto itself. Working with Linda has given me the chance to ask myself how ideas from the past live in the present. There’s something about the cyclical or recursive nature of time itself and the taste of time, the way in which you know where you are just by how people look at you… that reveals the force underneath social transformation. Because at the end of the day it’s all about getting fed, right? Linda’s vision as a creative person has been to hold those forms of sustenance together, which I think is something we could call black feminist practice – knowing that to make something, to feed ourselves and create an alternate vision of the universe, are all different names for a shared project. The show, by doing a careful accounting of the strategies and social technologies through which JAM was able to meet this basic need, is hopefully going to be able to offer all that up generously for folks.

Thinking about scale, has working on the project changed your own approach to curation, especially being in a larger institution like MoMA?

I think there are two belief systems: one is de-centering or decentralising, and with that I have to acknowledge that MoMA is a really important institution for a lot of reasons. In addition to its claim to history, it has resources, not only financial but in terms of the people who assemble there. It has an incredible ability to make ideas happen, to bring them to fruition, but it’s also just one of many different places. The challenge is how to point to and recognise its debt to those other places through the frame of an exhibition. This idea of de-centering is a passage into what a place like a museum might imagine itself to be in this moment, where people are looking towards museums to meet other kinds of needs that other cultural institutions might understand differently.

The other related idea is simultaneity, the idea that something can exist in multiple times and spaces, right? Can JAM constitute itself again or find some way of reassembling to take the utopian vision from the 70s and bring it on the road?

I like the way you’re talking about time, because Blackness’s relationship to time, and the ways time has been framed, is so particular. I think a lot about the work people are doing with the archive, and so I look forward to seeing how history is activated in the show but also becomes about the present and future as well.

What you’re suggesting is also incredibly practical and material. The theory of time you describe is everywhere inside of the archive that Linda has kept, and becomes a kind of score for its reconstitution in the future. I think much of what’s in that archive is about how it kept itself alive and the unlikeliness of it doing so against the odds of landlords and bill collectors and all the stuff that we know all too well that structures so much dispossession and trying to make it in this city. And to show that is to share a creative resource, not only as a blueprint for something, but also as a way to actually build out that vision.

As a curator, where do you see yourself fitting into these projects? How do you relate to them?

I find myself to be constituted by them. I think who I am, my own sense of self, is made through the relationships I create with artists. Luckily the things that I’m drawn to, or draw me to them, understand themselves to be alchemic formations that occur when you put a set of things that often don’t belong with one another but that together create something else. But I do feel like my own position, my own belief system, is made constantly through the process of devising and constructing space with others.

Maybe it’s about this transition thing we were talking about earlier. Here I am, looking at some piers functioning as this jetty. This little thing sticking out of land into the water is a way of imagining my role in terms of other vessels. If I receive the vessel, I’m the one who is there to help find some mooring but also send it off back into its stream. What I can do that’s of service is to help to create this perch from which you can jump into the water and swim for a little bit. And then where necessary, get a job and get paid, because we know that in New York City black people have often gone to the water’s edge to find work. To help constitute or send off a vessel feels like who I am inside of this art ecology.

Thank you so much, Thomas. Enjoy the rest of your day.

Thank you so much, Elodie. I really appreciate it. Enjoy your weekend.

Credits:

Photography Mario Sorrenti

Fashion Alastair McKimm

Hair Bob Recine

Make-up Aaron de Mey at Art Partner using Makeup Forever

Nail technician Honey at Exposure NY using Smith & Cult

Photography assistance Kotaro Kawashima and Javier Villegas

Digital technician Chad Meyer

Fashion assistance Madison Matusich, Casey Conrad and Jermaine Daley

Hair assistance Kazuhide Katahira

Make-up assistance Tayler Treadwell

Production Katie Fash, Layla Néméjanski and Steve Sutton

Production assistance William Cipos

Casting director Samuel Ellis Scheinman for DMCASTING