Every Sunday, in the Ghanaian surf village of Busua, young people descend on the burnt orange beaches after church to catch the waves. On his first pilgrimage to his motherland, Kwabena Sekyi Appiah-Nti joined them in the ocean — messing around with two boys from a neighbouring village who were doing backflips in the break. As they took turns to launch each other from their extended hands, Sekyi photographed them against the pale blue sky and churning waves. It’s a tender, dynamic image and the cover of his new zine Sika Kokoo, which explores the nuances of everyday life in contemporary Ghana.

Intimate, familiar and warm, the portraits are equal parts nostalgic, timeless and idealised, depicting a side of Ghana that’s different from the Western worldview Sekyi internalised growing up in a small town in the Netherlands. “A lot of things you see about Africa are [images of children] with flies on their faces, images of starving kids,” he says. “When I was younger there wasn’t Instagram, so the only places I saw Africa were on CNN or in books we had at home, but that doesn’t really give a good image of contemporary Ghana: how it really is now, what the youth is doing, what the music is doing.”

From biker groups to club culture, fashion and music — Sekyi found Ghana to be culturally rich and diverse. “Ghanaians are really creative people,” he says. “If you drive your car on the street, you see people on the side of the roads; they’re making couches, paintings… it’s really beautiful.” In the industrial estate of Abelenkpe, there’s a streetwear revolution led by Free The Youth — a collective of young creatives determined to empower Ghana through fashion and culture. Ghana’s afrobeats scene is also growing, catching up with nearby Nigeria, who gave the world Wizkid and Burna Boy.

Surprised by everything he saw — from the number of Porsches on the streets of Accra’s affluent neighbourhoods, to the scenery in the south that is so much greener than he had ever imagined — Sekyi set out to capture the realness of Ghana. He was mesmerised by the colourful three-day funerals that were equal parts mourning and music, with family members clad in red and black, singing and dancing. But it was the Ghanaian youth that really excited Sekyi, who photographed them “in a natural, normal, beautiful way; just hanging out or being at the beach or doing a sport,” he says. “It’s important to make images that show boys how I see them myself, growing up and being with their friends.”

“Everything I do, all the subjects I choose, have sprinkles of my childhood interests and current fascinations mixed into it,” Sekyi says of his work. Sika Kokoo is part of a greater personal project: Golden Boy, which captures Black boyhood in a palette of colours that radiate warmth and softness. “If you see certain groups portrayed in a different way than you normally see them portrayed, it can help you change your view of them,” Sekyi adds. “It can also help a group of people, if they have beautiful images of themselves, get a better self image.”

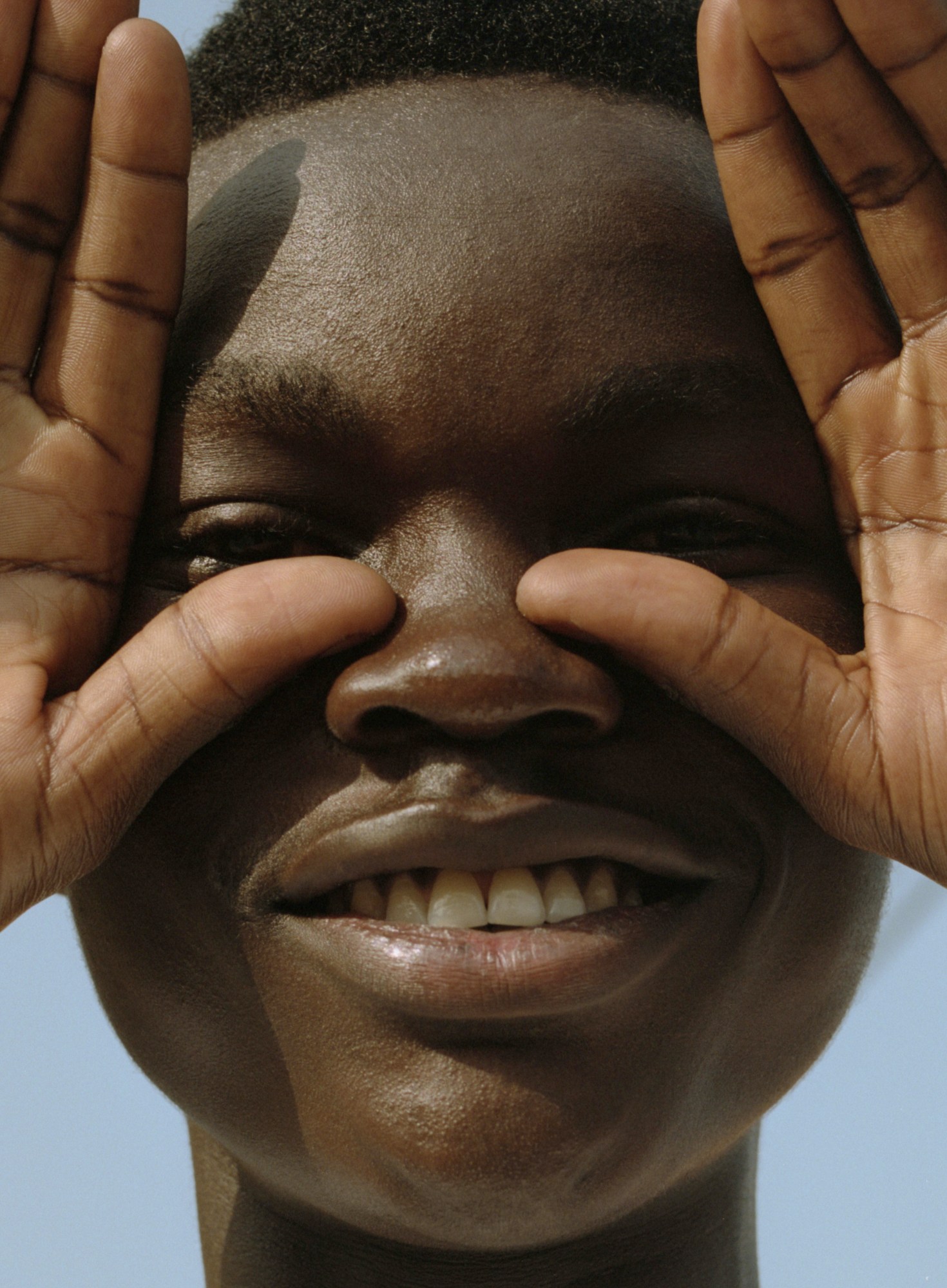

As such, his portraits are proud: a girl on a beach in a pink strapless bandeau glances at the camera, her blue contact lenses matching the sky; boys smile through hands that cover their faces; others seem to look wistfully beyond Sekyi’s lens. The photos could be taken in the 70s or 80s — one of his subjects, a model he met in Amsterdam on a shoot for the brand Daily Paper, wears a black string vest outside his family home in Ghana. A bedsheet frames the image.

Others ooze with vital energy like his photographs of Ghanian biker crews, which capture a softer side to the young men and their loud bikes that dominate the streets on Sundays — a mix of grandmas, kids and women with babies looking on. Sekyi documented the scene while clinging onto the back of a rider, in nothing but shorts and a T-shirt. “It almost felt like you were in a movie,” he says. It was nighttime, and he remembers seeing “guys going past while doing a wheelie. It was a crazy experience. I did it two times. And I was like, ‘Okay, it went good two times… let’s get out now.’”

In Sika Kokoo, photographs are interspersed with proverbs like, “Nobody knows the beginning of a good man” or “When two carry, it does not hurt” and sketches of gold Ghanian tribal objects and jewellery. Gold is a theme throughout the book, holding the dual meaning of being a good, worthy person, and that of the precious metal. “In Ghana, there’s a mining culture,” Sekyi says, of the former British and Portuguese colony that formed part of the Gold Coast. “My dad always had a gold chain or my mum always wore gold rings.”

One of the backflipping boys was a gold miner, and a tattoo on Sekyi’s arm caught his eye. It features the words: “Stay Gold” below the Fibonacci spiral — a symbol used for centuries by artists, architects, musicians; and later photographers in their compositions. It refers to a divine proportion recorded by Renaissance artists that can be found throughout the natural world. In the prologue to the zine, Sekyi writes of a similar perfection he found on his return to Ghana: “During my first stay in my fatherland (December 2019), I found a paradise that I felt deeply connected to. I felt so welcomed by the friendliness and openness of the people that I met along the way,” he says. “I returned home with a much clearer outlook on life. In the past few years, I’ve embarked on a journey to discover myself: my identity, what I want to do most in life and with whom I want to spend it.”

Sekyi didn’t grow up with his Ghanaian heritage and language taking centre stage, as a child of the African diaspora living in a suburb outside Amsterdam. And his father shared little about the village, a few hours outside of Takoradi, where he was raised — what he did share, Sekyi struggled to connect with. Returning to Ghana has changed that. “I’ve dug deeper than ever before and I’m still working on learning as much about my culture as possible, with my father happily guiding me on my journey this time round.”