On Halloween in 2005, filmmaker Ross McDonnell was walking through Ballymun, a suburb on the northern edge of Dublin’s Northside, when a teenager approached him. The boy, a resident of the estate’s notorious tower blocks, led him to a roaring bonfire composed of cars and debris, a beacon of destruction among the concrete. Carjacking, joyriding and arson were commonplace in Ballymun, as much acts of recreation as criminality in one of Ireland’s most impoverished areas. Ross, a Dublin native who for years had driven past the seven towers as a film student, felt compelled to document their residents, so often caricatured according to Ballymun’s reputation for drug use and deprivation — but rarely afforded the chance to present their own perspectives.

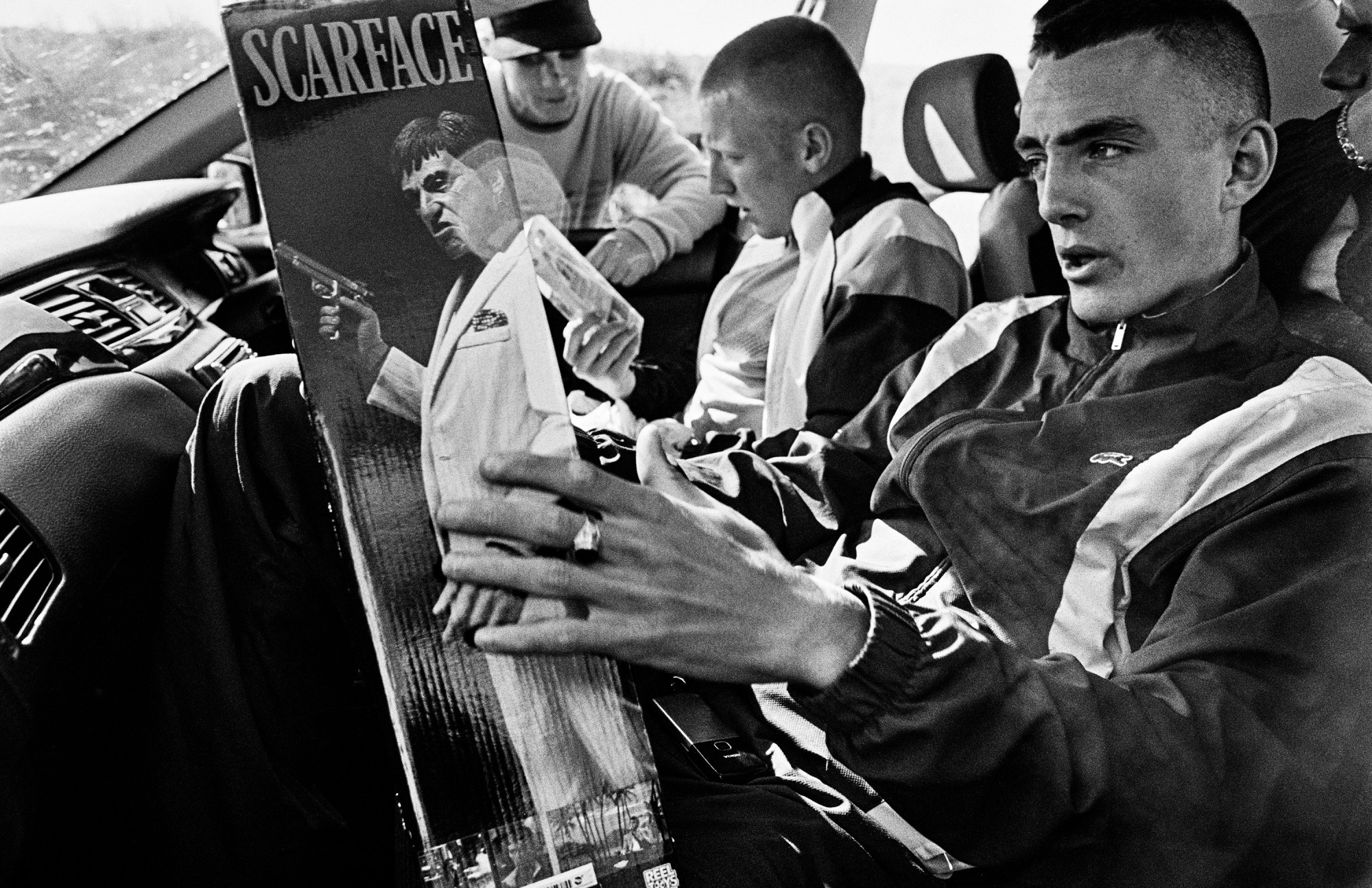

Ross took photographs in Ballymun for the next six years, remaining in and around the community until 2013. His project, entitled Joyrider, presented life on the estates (known colloquially as ‘The Block’) through the eyes of its mostly male youths, their lives a mixture of hardship and hedonism. Drug dealing, joyriding, and vandalism are captured with a poignant touch; in one image, a man cradles a double-barrelled shotgun as light falls gently on a sofa behind him. But Joyrider is also marked by community spirit, stoicism and humour Ross first identified on that Halloween evening. A man sits in a car holding a Tony Montana Scarface doll, his expression wry and knowing; another cushions a toddler in an armchair while relaxing with friends, a simple act of care in a graffiti-ridden flat.

Ross paraphrases writer Dermot Bolger, who wrote a trilogy of plays about the town, when describing Ballymun. “A place 15 storeys high and a million stories deep.” A decade since the last image was taken — and six years since the final tower was demolished — Ross is now publishing Joyrider as a photobook. Ireland is today wrestling with the same debates around housing which spawned Ballymun’s development in the 1960s. Ross’s chosen edit of the series evokes the state’s failure to deal with “the cyclical problems relating to class, housing and addiction”, which defined his time in the suburb, he says. But Joyrider has a unique temporality: what does it mean to tell the story of a place that no longer exists? And does photography help or hinder us to disentangle nostalgia from reality?

State failures in Ballymun stretch back six decades. Plans for its development were masterminded in the early 1960s in response to unsafe conditions in Dublin’s impoverished tenements. Inspired by projects in Paris, Stockholm and Copenhagen, minister for local government Neil Blaney signed agreements in 1965 for 3,068 dwellings, making Ballymun Europe’s largest industrialised housing contract. The seven main towers, each standing at 15 storeys and comprising 90 flats, were completed four years later, accompanied by 19 eight-storey blocks and 10 four-storey walk-up flats. To mark the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising — and in a symbol of the project’s distinctly national optimism — the towers were named after the signatories of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Clarke, McDermott, McDonagh, Pearse, Ceannt, Connolly and Plunkett immortalised in steel and concrete, guardians of a new era of Irish modernism.

At first, Ballymun’s residents were pleased with their new homes, the population numbering roughly 13,000 by the late 60s. But problems with heating, broken lifts, vandalism and social isolation emerged. The estate had only one access road, and the promised recreational facilities — a swimming pool, dance hall, bowling alley, restaurant, creche clinic and Garda station — were never built, while basic shopping amenities remained scarce. By 1974, the Architects’ Journal had declared the tower blocks a “disastrous” solution to mass housing.

In the decade that followed, flats emptied as wealthier residents left. Opioid addiction and mass unemployment (according to one Irish Times report, as high as 45% by the mid-80s) took hold, to the extent that Dublin City Council had to reject calls for the towers’ demolition in 1984. That same year, the Bank of Ireland announced it was closing its single Ballymun branch — a sign of dwindling faith in the area and its residents’ prospects. As the Ballymun Task Force noted in 1987, vacant flats, drug problems and vandalism “all combined to give the impression of a community falling apart at the seams…a purgatory unfortunate souls had to pass through before moving on to greener pastures.”

By the time Ross arrived in 2005, a 1997 regeneration plan promising to transform Ballymun into “the capital of northside Dublin” had stalled. The council-owned Ballymun Regeneration Ltd had boasted of interest from US and Chinese property groups during Ireland’s Celtic Tiger period, only for a lack of investment and the 2008 crash prompting its decommission in 2013. Again, a promised bowling alley, cinema and new shopping centre (to the tune of €800 million) were never built. The Block’s planned demolition was also delayed, Pearse Tower’s toppling coming four years behind schedule in 2004.

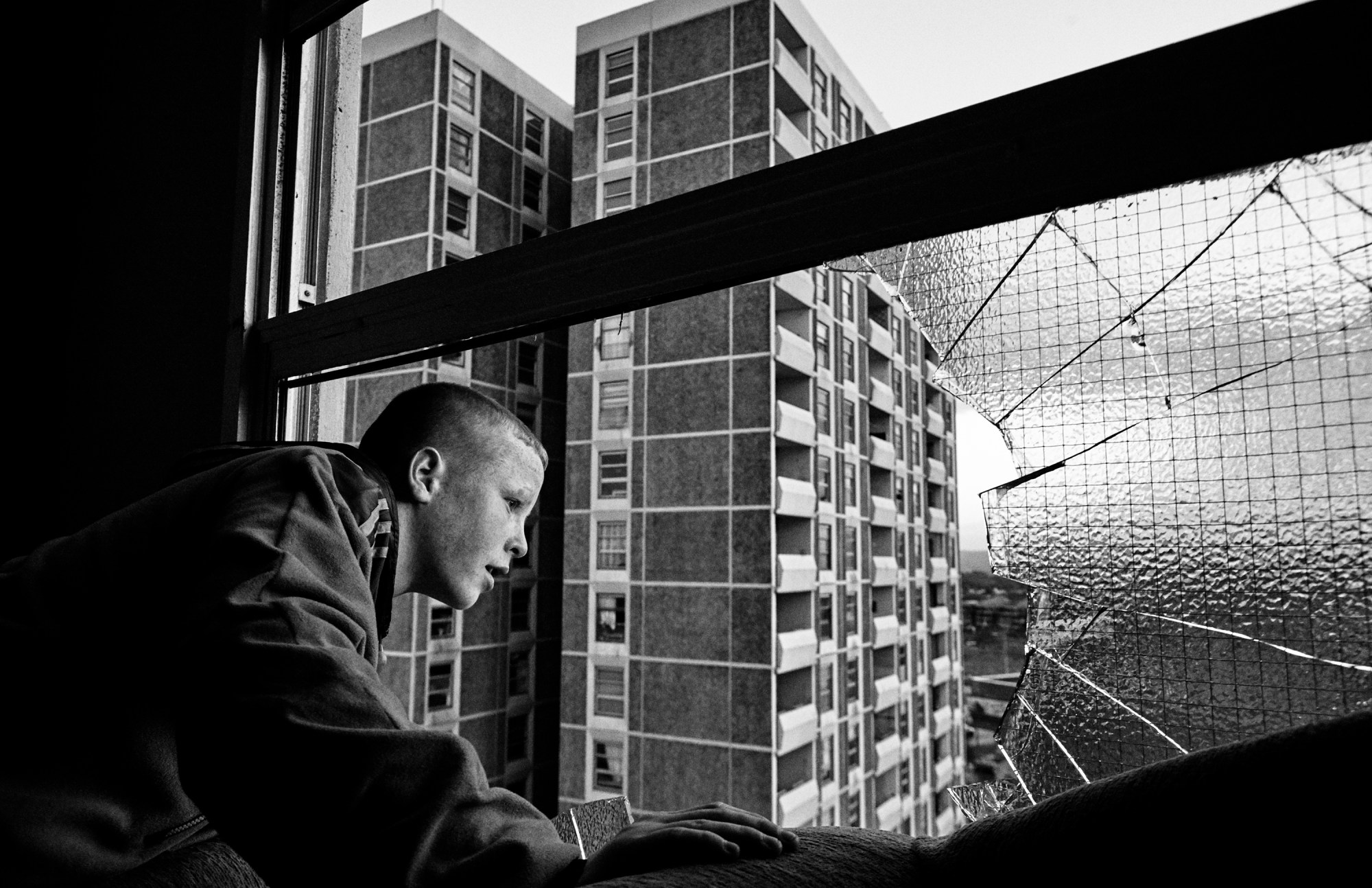

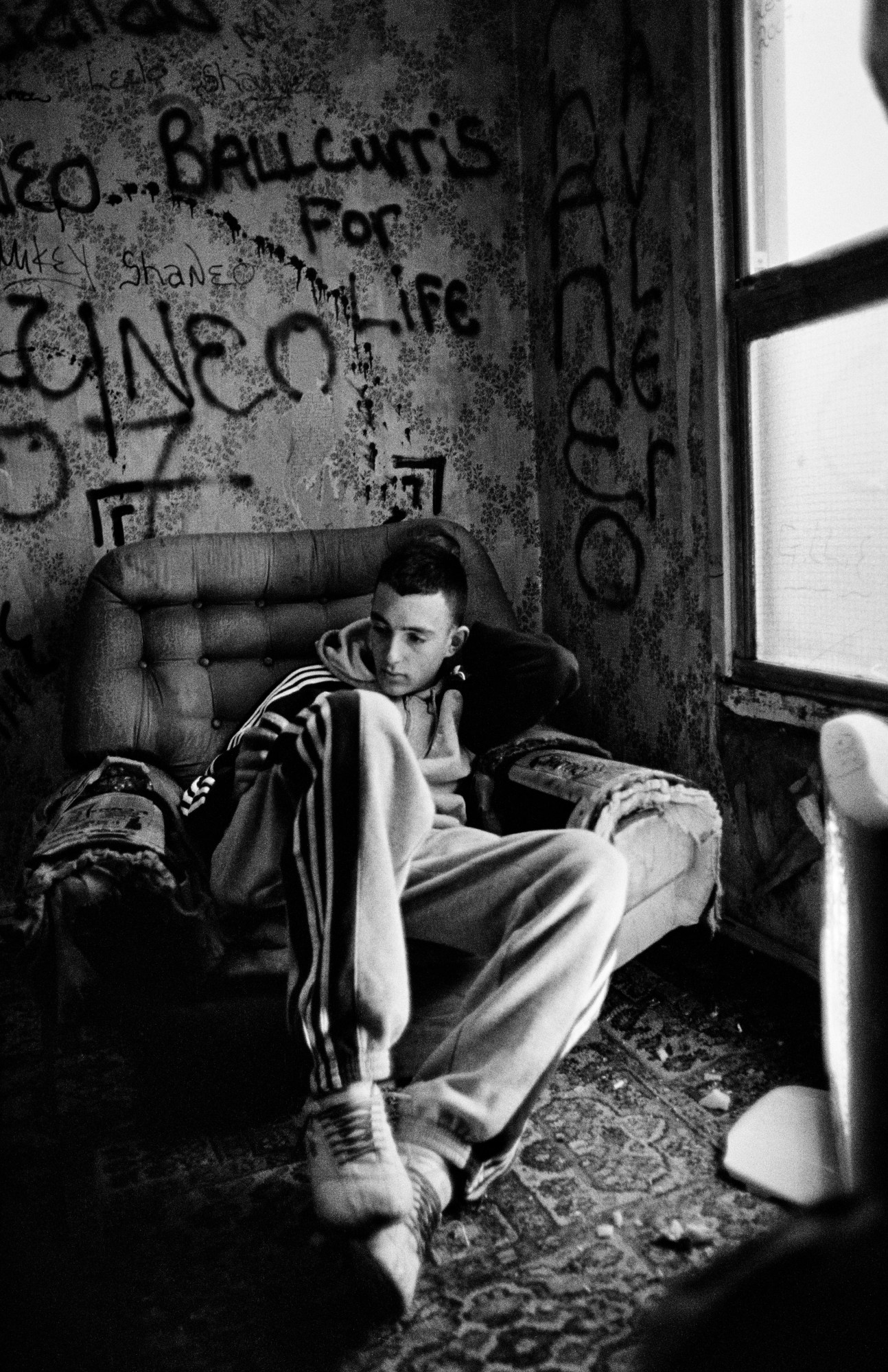

This meant that entire blocks were periodically vacant during Ross’s time in Ballymun. Joyrider shows boys moving through the abandoned structures like a giant playground, cutting security doors with disc cutters, leaping from stairwells and crowding balconies like observation towers. Different communities would colonise the structures, creating a nomadic culture at odds with the flats’ original purpose — and the isolation they once enforced on residents. Ross recalls religious groups moving into the blocks to lead addiction clinics and offer food provision, even when flats were being torched and used for drug-taking. The monochrome images give the flames — engulfing upturned motorbikes and cars, or captivating a boy wearing devil horns — a sense of purity, brilliant white flashes with a supernatural aura.

There is a paradox at the heart of Joyrider, which Ross details in heartfelt terms. The Ballymun development represents successive failures in state planning, social policy and community outreach, and yet there remains a deep nostalgia and affection among the residents — towards the buildings themselves and the lives they led there.

Feeling rejected by the government and Irish society fostered a sense of pride and defiance. Tight-knit families would stop the police from being overly aggressive with their sons, and would create their own community programmes where the council had failed. Closeness and trust are conveyed through tactility in the book: boys pile into cars, hold each other tightly on motorbikes, and huddle while smoking in dark doorways. In one image, 13 boys line a balcony while two firemen extinguish a burning motorbike below. “Fuck the Garda” graffiti is visible in the background. Strength is drawn from shared values, but also the comfort of outward sameness. One of Joyrider’s most arresting images shows six boys wearing Adidas tracksuit bottoms and Nike Air Max trainers. Streetwear as uniform; one identity shared among many. Joyrider, singular.

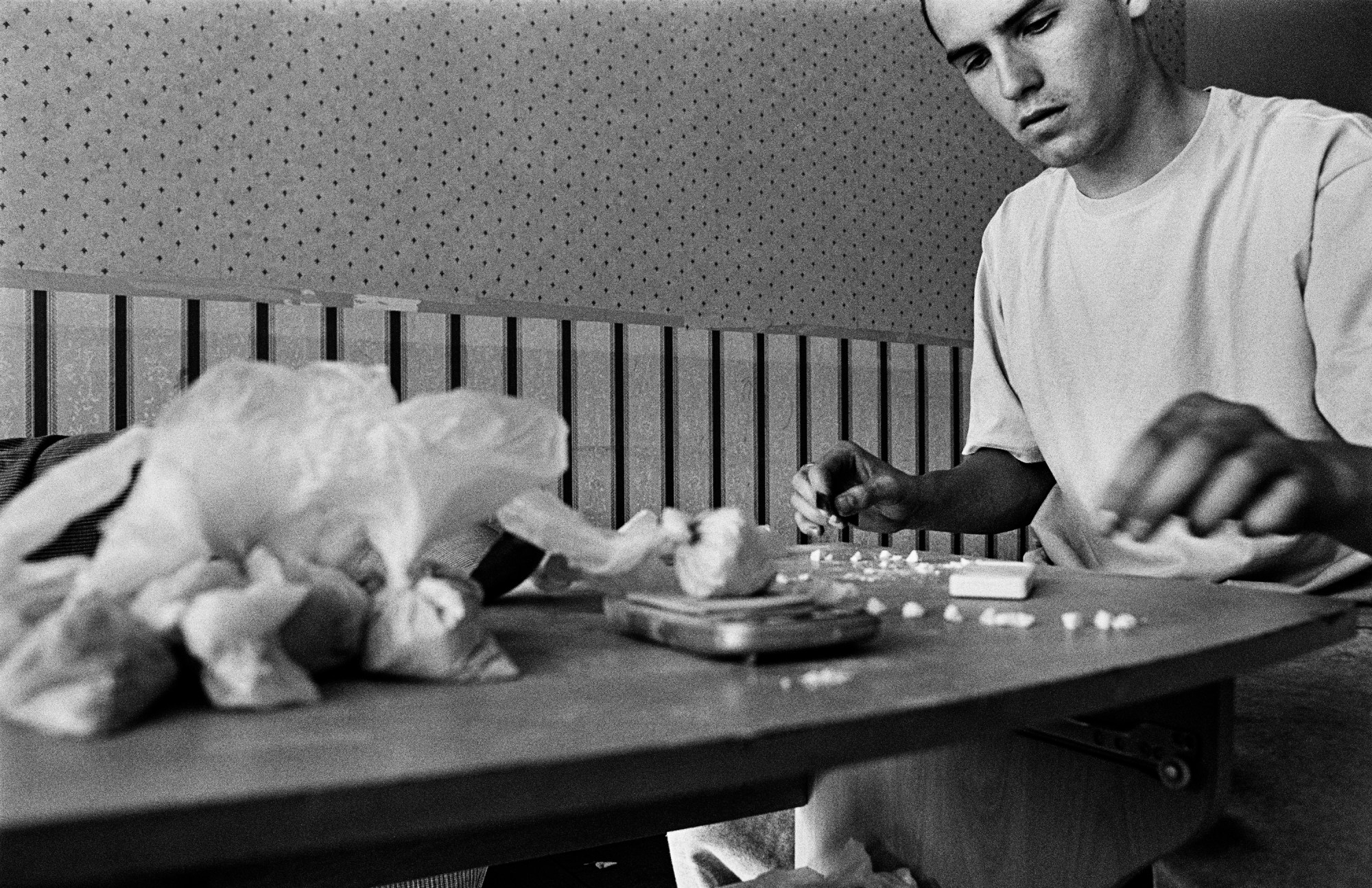

The photographs of lone subjects are more introspective, referencing the private struggles and survival tactics of life on The Block. Joyrider’s penultimate image shows a shirtless man looking into a dirty mirror, his gaze low in contemplation, his posture suggesting fatigue. In earlier consecutive panels, a boy lies on a sofa bed, smoking a cigarette and staring lazily at a mobile phone. A cupboard door removed from its hinges leans against the adjacent wall, a life dismantled piece by piece. Next a man sits at a table dividing cocaine from plastic bags into delicate wraps, calm and fixated, while again, the wallpaper — this time part-stripe part-polka dot — lends the scene a domestic nostalgia, as if the flat’s past is witness to its new function.

How to reconcile these criminal acts — here documented rather than glorified, but nonetheless aestheticised — with their impact on the wider community? Ross describes a subculture whereby joyriding, theft and drug dealing were fuelled by a mixture of necessity and boredom, and so were effectively decriminalised. “The line between being empathetic and humanising these kids as not a social scourge, or using tropes around gangs and violence, is very important,” he explains. Drug dealing especially is symptomatic of a lack of employment opportunities and social security. And if it’s already happening, the decision to partake feels insignificant. “It’s young people trying to find their identity,” Ross says. “These acts are perceived as violence by society, but here they’re okay and so are not experienced as criminal; they’re experienced as expressions of freedom, fun and relief from boredom which young people participate in everywhere.”

To an extent, Ross shares his subjects’ nostalgia. Not just for the buildings and community spirit, but for the photographic process. The excitement of travelling with the pack is clear; the thrill of documentary as a creative pursuit addictive. Joyrider is part-eulogy, part-polemic. Its political power comes not from its execution or curation — the book is without text or manifesto — but from Ballymun’s ongoing condition, the state failures and neglect which confer forebear status on its characters.

Ballymun continues to be subject to state reports. In 2017, Dublin City Council outlined a vision to create “a successful and sustainable new town with a thriving local economy that caters for all people.” This year, a summer consultation relating to a new central plaza stated a desire to “soften and ‘green’ the space” after concluding that the existing design “does not create a distinct sense of place within Ballymun.” The council’s report — “Ballymun – a brighter future” — published earlier this year, details the extent of addiction, open dealing, and drug-related crime, which has doubled over the last four years. Crack cocaine is being pushed by gangs targeting the area for its high number of heroin users. Male unemployment remains 50% or higher, and at least 10 more social workers are needed for child protection.

Ross suggests a connection between the towers and attention on Ballymun — a sense that something more than memories was lost during the demolition. The fact that people are no longer living on top of each other has altered the shape of the community. The towers were “a very visible representation of negative social connotations which brought attention and regeneration,” he says. Now that the structures are gone, the town and its issues are easier for the state to ignore. Nearby, Dublin’s housing crisis intensifies with every passing day, while server farms line routes to the city’s north and west. In one photograph, a boy leans out of a window with a tower looming behind him, perhaps gazing upon land which foreign property developers now prize. “This cycle continues in Ireland,” Ross says. “Of land, how we identify with land, and how the government uses land. That’s embedded in the Irish psyche, and always has been.”

Ross McDonnell – Joyrider photobook talk and launch takes place Thursday 21st October 7pm at the Gallery of Photography Ireland. Purchase here.

Credits

Photography Ross McDonnell