In the introduction to Michael Bailey-Gates’ new monograph A Glint in the Kindling, writer Cyrus Dunham recalls their image being captured by the photographer: “[In] photographing me, Mike created a kind of container. I do think that’s a big part of what Mike does — seeing into people, and then letting them play towards their own fantasies. That changes people, and they end up doing things they might not have otherwise, if they hadn’t had the chance to do it in front of Michael’s camera.”

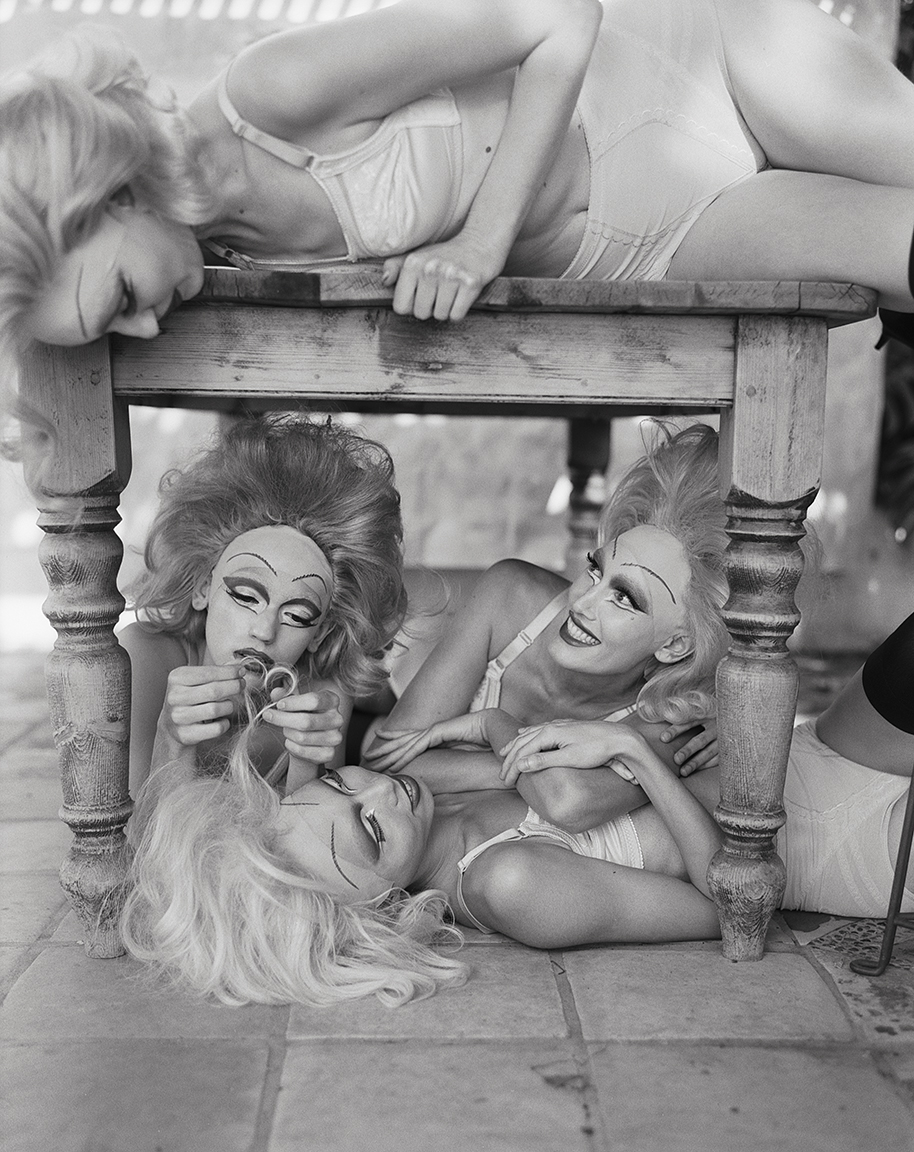

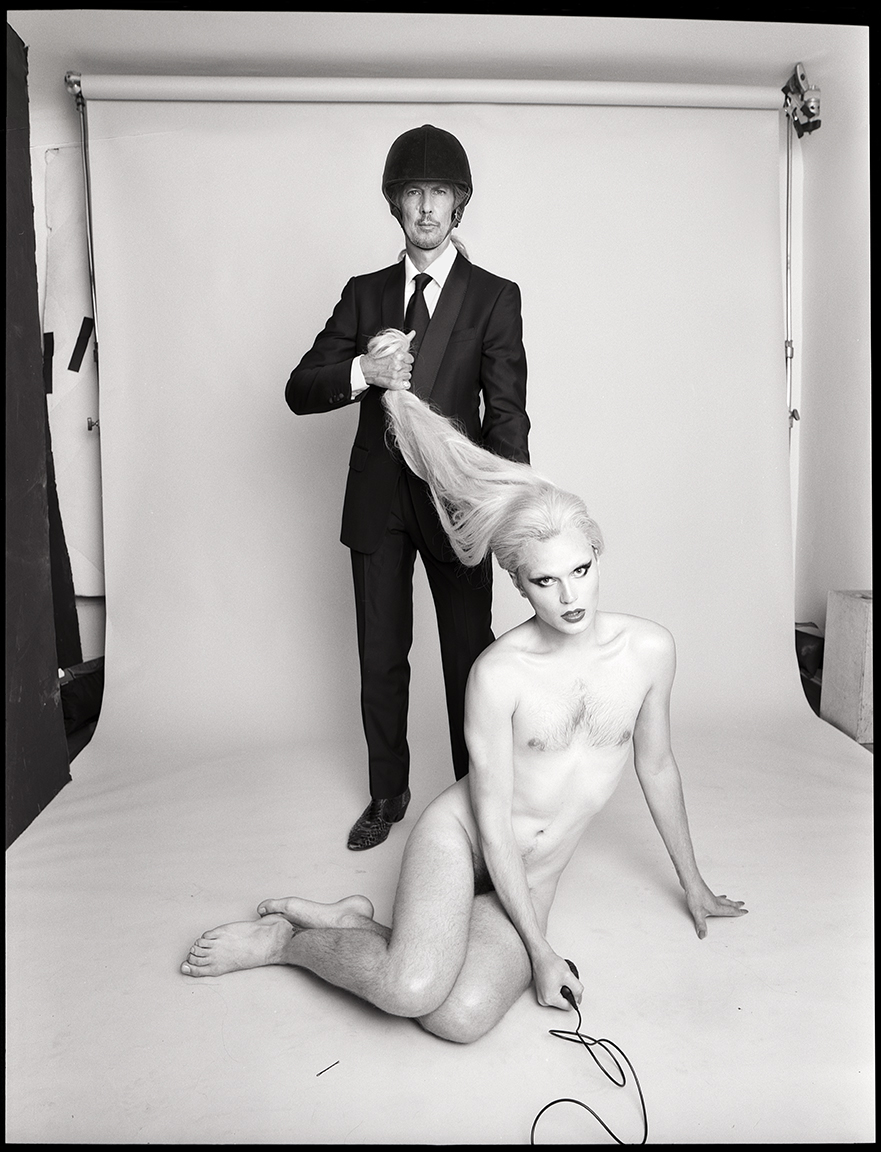

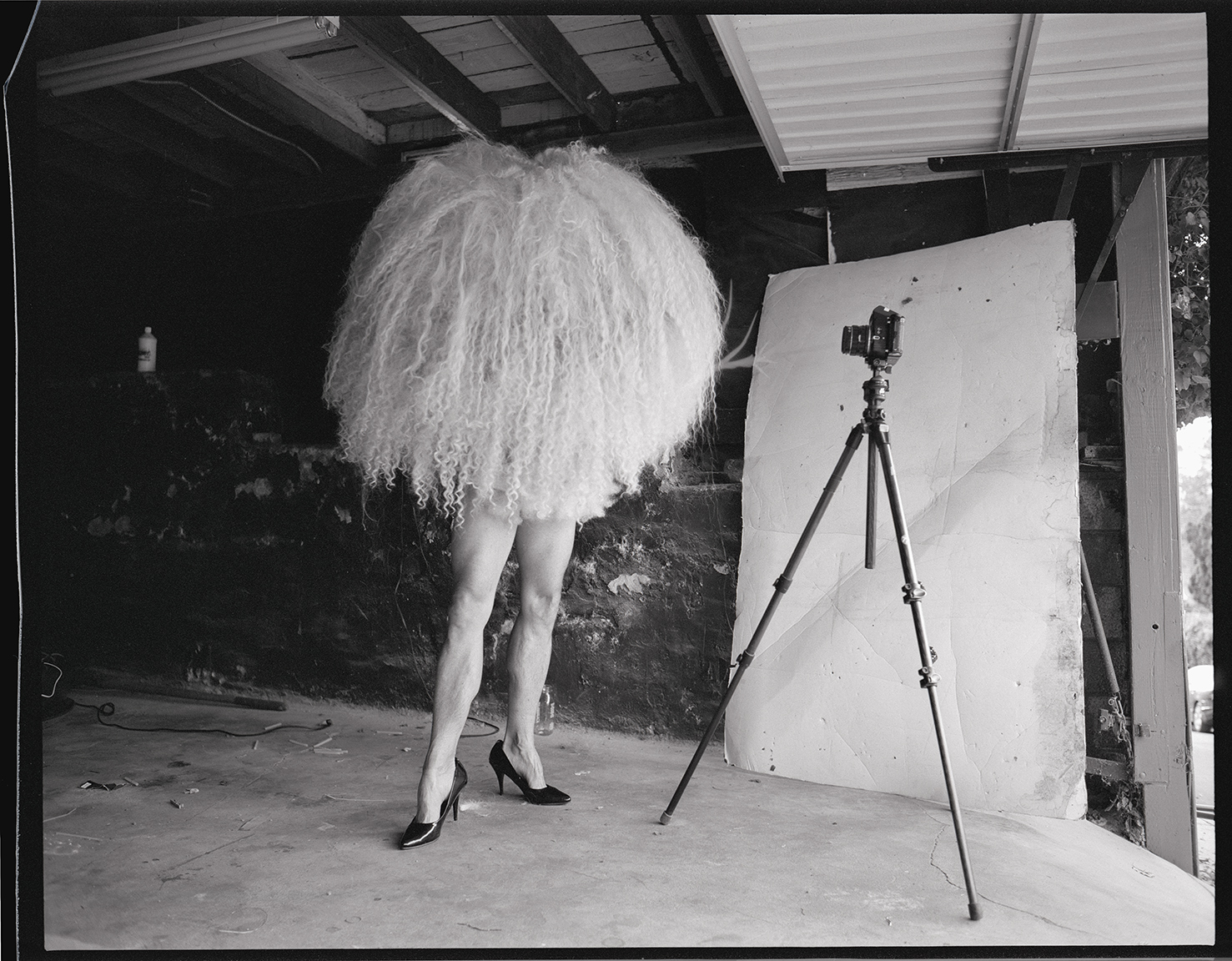

This quote sums up Michael’s practice as a photographer — the way they use a combination of studio technique, hair and makeup, and an unbridled sense of curiosity and joy to play with social norms. There’s a sense of added transparency in it, too, as Michael lets the viewer into their image-making process via visible tripods and backdrops, varying studio locations. Over the years, Michael’s work as both a fine artist and editorial photographer has been featured in outlets such as Vogue, The New York Times, and of course, i-D. Now, A Glint in the Kindling compiles their sleek yet imaginative portraits of themselves and a tight-knit circle of creative collaborators that cleverly subvert — and transgress — strict binaries of gender and sexuality.

To celebrate the release of their book and the opening of its accompanying exhibition at Amsterdam’s Ravestijn Gallery, Michael Bailey-Gates tells us about their recent work, queer representation and the possibility for transformation in front of the camera.

How does it feel to have your work in a public space and have people reflect on it communally?

It’s really beautiful. Amsterdam was so kind and welcoming to the work. In the past seven years, my life has been such an up-and-down roller coaster, and sometimes, it felt like I was working in the dark — kind of blind and not really sure where it’s going to go. So, I’ve just been following my heart in making it, to see it presented and know that there was a place for it to live was really affirming.

Your work has a lot of visual references to classical studio photography — you can see the studio backdrop and your camera in the background of these images. Can you talk about some of your influences as a photographer, and how they relate to this set of images?

The idea behind the title for the book is this idea of a beginning, and showing the transparency in my image-making by showing my studio is part of that. I think it speaks to the subjects, too. There’s a transparency in their gestures, and there’s a lot of self-reflection in the people I photograph, too. So, as far as influences go in my work, I’m just really influenced by the people around me. I always think back to this thing I heard when I was in school — it was this idea of photography acting like the ring that’s leftover if you leave a water glass on the table. I’m not sure who came up with that, but I thought it was so beautiful. You’re leaving an imprint of your existence. And I think in my photography, I’m really influenced by that idea of leaving an imprint of myself and people around me.

Yeah, especially since these photographs are picturing queer identity in a way preserves this moment in time for future generations. Photography can be such a wonderful medium for artists to explore gender and sexuality because you can really play with some of these gender roles and presentations. It’s almost like an act of queer self-determination.

I think with photography, people believe it. It comes with this idea of truth. Obviously, that’s changing since everybody can now create their own images, which is great, but you may exaggerate yourself a bit in a photograph. If your photographs include these kinds of transformations, I think people see it and believe it. Photography has historically been this reflection or souvenir that you can show to people, but this magical thing does happen when you use a photograph as a souvenir to bring into the future. There’s such a possibility for transformation in photography.

The photographs in A Glint in the Kindling are a mix of portraits of yourself and others. How do you conceptualise your self-portraits in comparison to the portraits you take of your peers?

For me, self-portraits are kind of inescapable. I don’t necessarily think of my work in the category of “self-portraits,” and sometimes, I wouldn’t want them to be described that way. I’m included in them, but I also feel like I’m a part of a group even when I’m alone. The language around photography can be so rigid, and when I read about it, it feels outdated — like, it’s almost taboo in art photography to bring up that photography is now so accessible to everyone. Everybody makes pictures and self-portraits, but it’s more than just that strict category. I think that is my approach to photography, that it allows for universal growth.

It’s interesting to think about the way identity functions in photography and self-portraiture. You’re not just capturing your own personal history through it, but also the evolution of the medium and the way we use it. What we think of as the past figures so heavily when we talk about photography.

Totally. My friend Bobbi said it really well; they said that people use the language of mourning in relation to their transness, and I think about that term and the language of mourning so much — especially in photography. I’ve always tried to revolve around this idea of joy, but more so in this body of work, I think our own self is the only thing we can really speak the truth about, and everything else is just a wild guess. In making this work, that was really the point. I feel so comfortable speaking about myself and the people around me because that feels really honest.

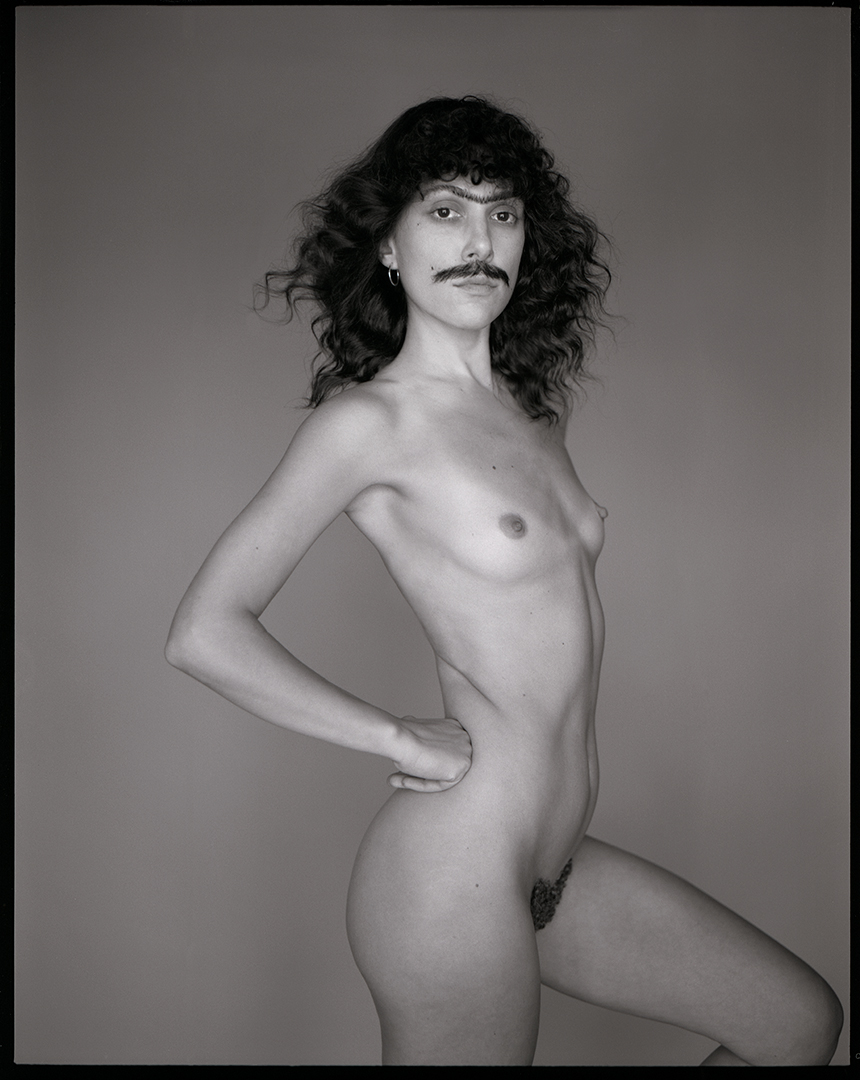

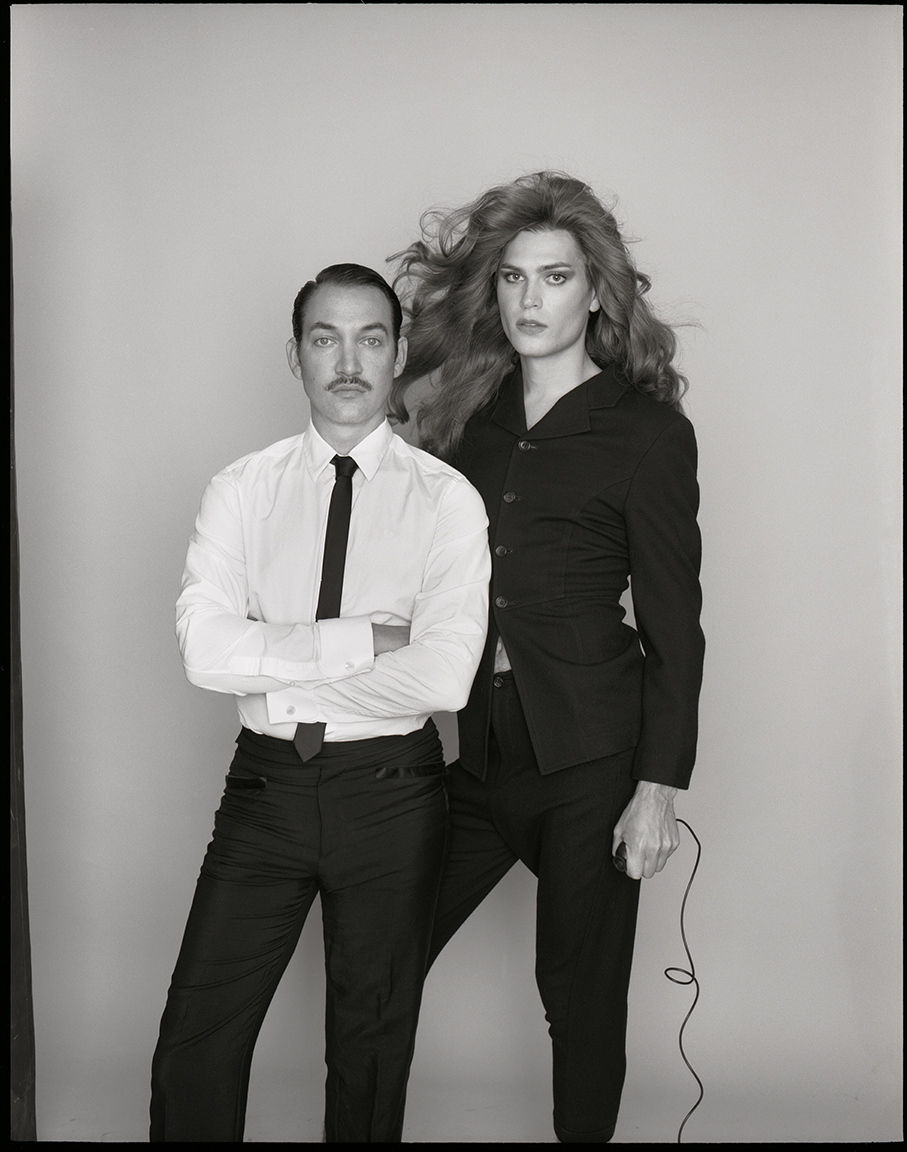

That’s a really beautiful way to put it. You’re giving photography a chance to play around with presentation and lean into what some people would view as opposites or contradictions within yourself in a really holistic and joyful manner — these binaries we’ve conditioned ourselves to follow don’t have to exist. I’m thinking specifically of the photograph you took of [artist and Puppets and Puppets designer] Carly Mark, where her body is represented in a pretty traditionally feminine way except for the moustache on her face.

Carly talks about this picture a lot. She’s like, “It’s my favourite picture; I just wanna be like that all the time.” I really take those little conversations to heart because hair and makeup artists are so overlooked. We go and see different doctors and healers and intuitives for all these problems in our lives, but hair and makeup artists get so overlooked as these keepers of seeing different versions of ourselves that we get to experience, and maybe that changes our relationships to other people when we see those parts.

What I love about the way you use hair and makeup in your images is that you use it as an extension of self.

Yeah, and I that’s when we see ourselves in new ways, that’s when we get to imagine new ways of being in relation to those around us.

A Glint in the Kindling is available for purchase here. Michael Bailey-Gates’ work is on display at the Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam through October 23.