Who is Julian Ungano? That’s a question that the photographer and filmmaker is used to hearing in rooms where people assume he’s not present. He’s an unassuming character: an artist who, at one stage, was turning up to take pictures with barely anything on him bar the camera itself. That was the case the first day he met Timothée Chalamet in a cottage at the Chateau Marmont, shortly before Timmy walked the red carpet at the 2019 Golden Globe Awards, where he was nominated that night.

Julian remembers that night vividly, mostly because he recalls it being framed in his mind as the last photographic job he’d do before giving things up. A change in the photography vanguard meant he was, back then, working less than he had before. Until Cartier came calling and asked him to take portraits of a mysteriously unnamed young actor before an awards show. He had an inkling it was Timothée.

“I rolled in with, like, no assistance,” Julian recalls, talking from a Paris hotel room the night after Dune had a special screening. “I had two cameras and a duffel bag. That was it.” Timothée sat on a chair in the garden, surrounded by none of the frills most photographers bring with them. What Julian captured feels like one of those crystalline moments for a Hollywood star that live on for decades. Like portraits of young Leonardo DiCaprio or one of the Brat Pack. “I think he saw that I wasn’t a psychopath then. We did some shots and he went off into the night. It was honestly a perfect intersection of luck and making the most of an opportunity that was given to me.”

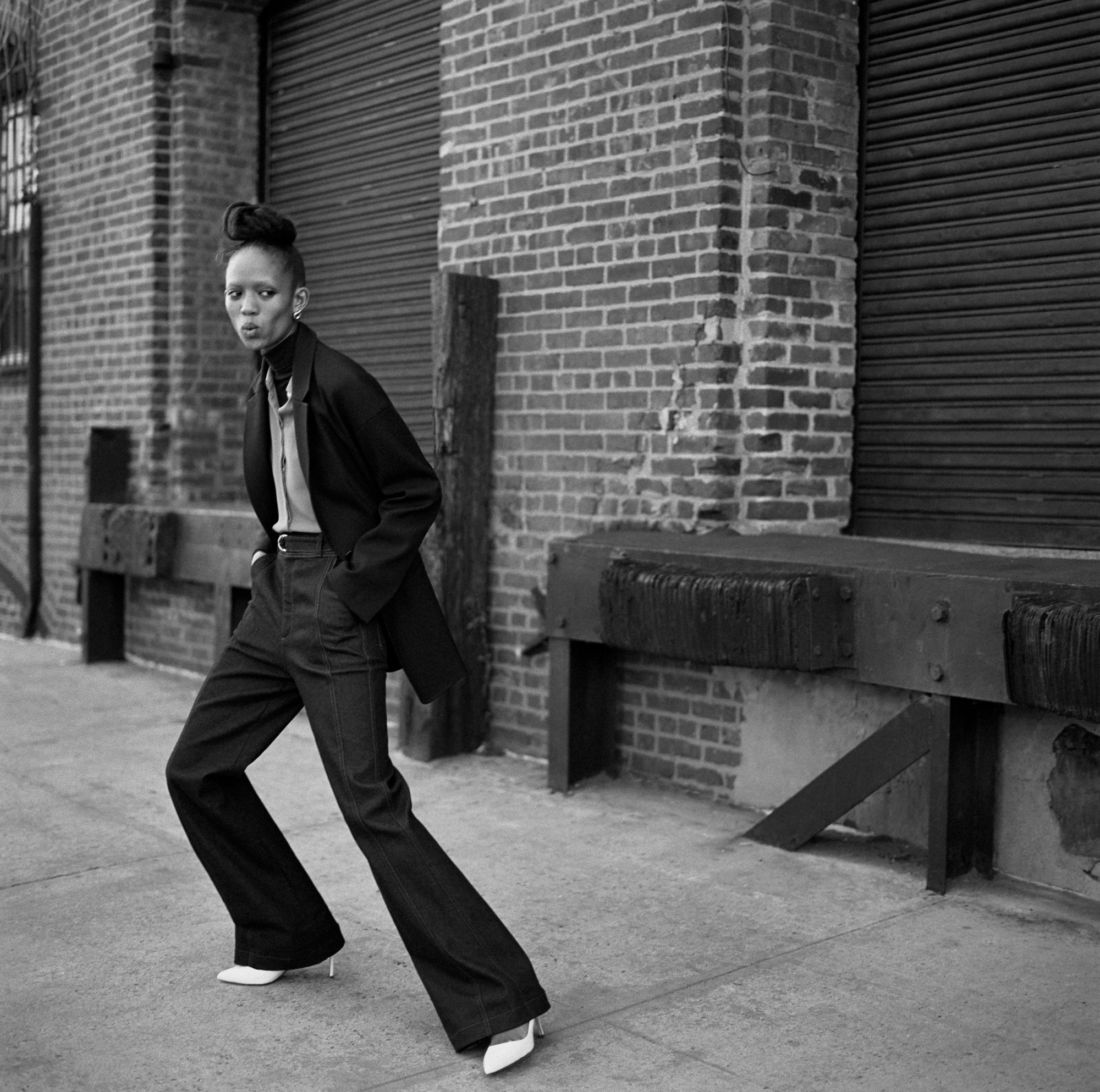

It kickstarted a new era in Julian Ungano’s career: today, alongside writing and directing short films and working on editorials for magazines, he tends to be the go-to guy for celebrity photography that sensitively tells the story of a moment. As well as Timothée, who he’s been spotted with everywhere from Cannes Film Festival to last night’s Met Gala, he’s also been called upon to capture portraits of artists like Lily Collins and Talia Ryder too. He sees it as a chance to look beyond the posed nature of editorial, and capture some of the most recognisable faces in those rare moments before the whole world sees them.

“I’ve personally never seen myself as one thing,” Julian says of his multiple practises. “I have rampant ADD. You know, when I’m at home working on something, I’ll be retouching or editing photos for 25 minutes and then I’ll get bored of it and immediately go to start working on something like a movie script idea that I have.”

Julian grew up in Vermont, the child of two Europeans who encouraged him to explore, and leave at the first possible opportunity. Stories that he’s put to screen reflect on this early life and the confines and complications of his hometown. The short And After All was written in the aftermath of his mother’s death in 2011, which followed the loss of his father at 15. It chronicles the story of a young woman returning from New York to her old hometown. His most recent, State of the State, unpacks the opioid crisis in Vermont through the lens of a desperately in love couple.

This paired respect for both film and photography (he was a Pratt film student before assisting David Lachapelle) compliments a lot of Julian’s work. An image is never just an image: it usually captures a split-second moment in the subject’s life, but will come, in future, to represent not only that moment, but a whole era of their career. The most time he’s spent actually shooting a celebrity client? “Probably 20 minutes,” he says. “But I would say, on average, it’s like four minutes.” Sometimes, in the most high pressure situations, all he’s got is two minutes to get the best shot.

“I’ll joke around when [Timmy and I are] in a room together and a song comes on. And I’m like ‘You weren’t even fuckin’ born when I was jamming to this album’,” Julian says, laughing. “90% of the people I work with were like that. Growing up, I remember my sister having pictures of DiCaprio and Corey Feldman in her room… those teenage heartthrobs.

“Now we’ve seen them grow up and they’re adults. Those people are in their late 40s or aren’t even with us anymore. What’s interesting about shooting people, like Timmy right now, I started working with him before everything blew up. It’s cool to know that in 25 years, all of this will still exist.”

All imagery courtesy of Julian Ungano