The Harold Hunter Foundation — named after legendary NYC skater Harold Hunter, who passed away in 2006 — is a New York City-based non-profit that provides safe spaces and resources for skateboarders to develop professional and life skills, network inside and outside of skateboarding, and, of course, skate. Co-founder Jessica Forsyth was a close friend of Harold’s and a part of the skateboarding culture captured in Larry Clark’s Kids. They even filmed parts in her childhood home, then a safe space and refuge for the NYC skateboarding community. Reflecting on the itinerant existence of these OG NYC skaters in the 90s and early 00s, Jessica said, “They didn’t have skate parks, no cell phones. It was a really small community of ragtag lost boys roaming the streets all night.”

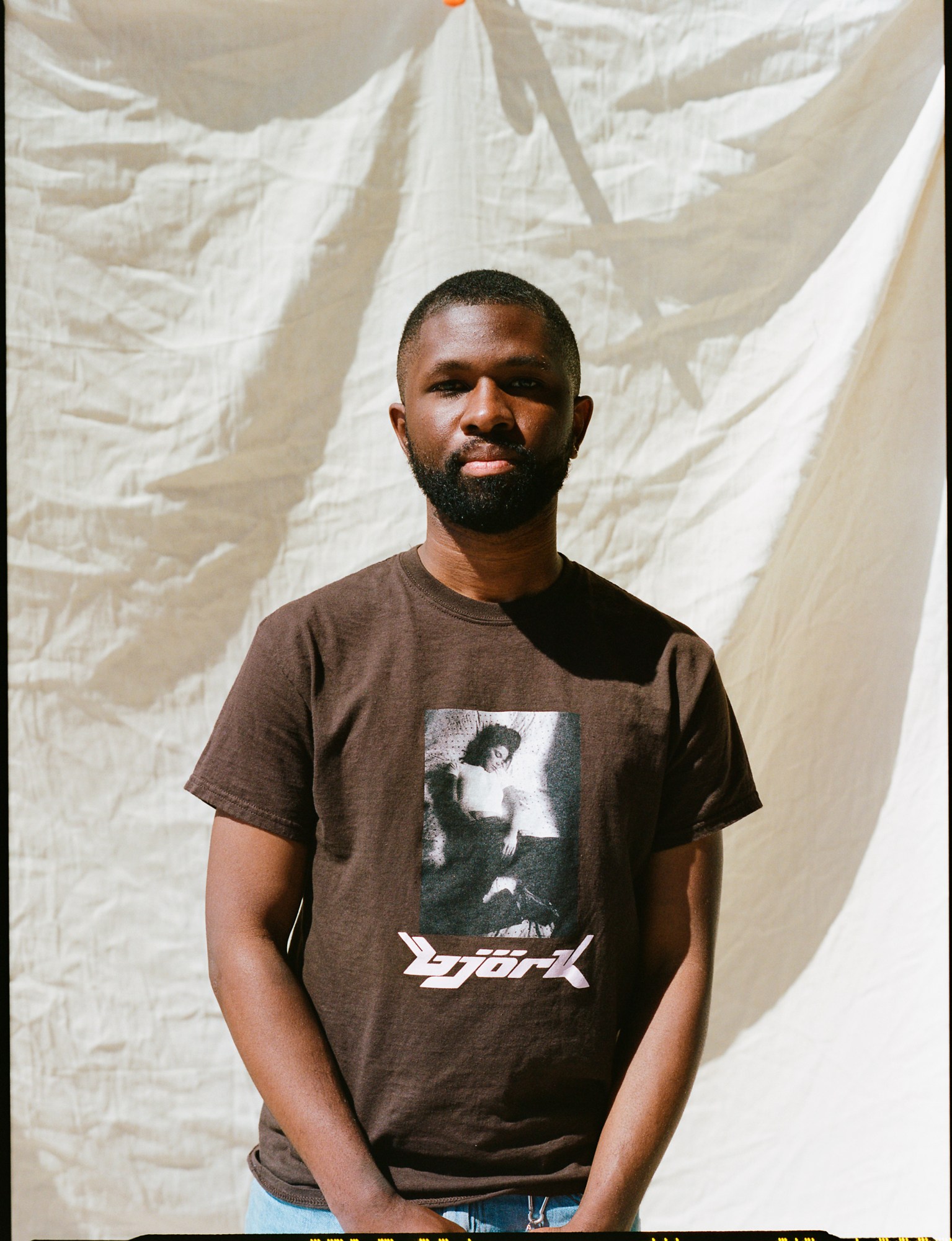

Olu Stanley speaks about skateboarding in New York City with a bravado that I’ve learned is the norm, necessary even. “Just being up here at the courthouse, being a skater, we had to fight almost all the time,” the coach and mentor at the foundation tells me, standing outside the courthouse on East 161st Street in the Bronx. “They looked at us just like, oh it’s some corny white boy shit, they soft let’s go fuck with them. We had to fight to let them know, we come from the same place you come from.”

For me, a skateboarder who grew up in San Diego and Los Angeles, the contrast to skateboarding in NYC — really skating in the cut — was disconcerting. I wasn’t ready for the amount of time you were out on the streets, navigating between cars, over cracks and potholes, nor, in my first home in the city — on the corner of Bedford and Nostrand, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn — did I expect the attention from the neighbourhood that a skateboard would bring you.

“It was different for me being a kid, growing up in the Bronx,” Olu says, “I felt like a target because of the skateboard, it wasn’t the cool thing to do, the hood wasn’t accepting it.”

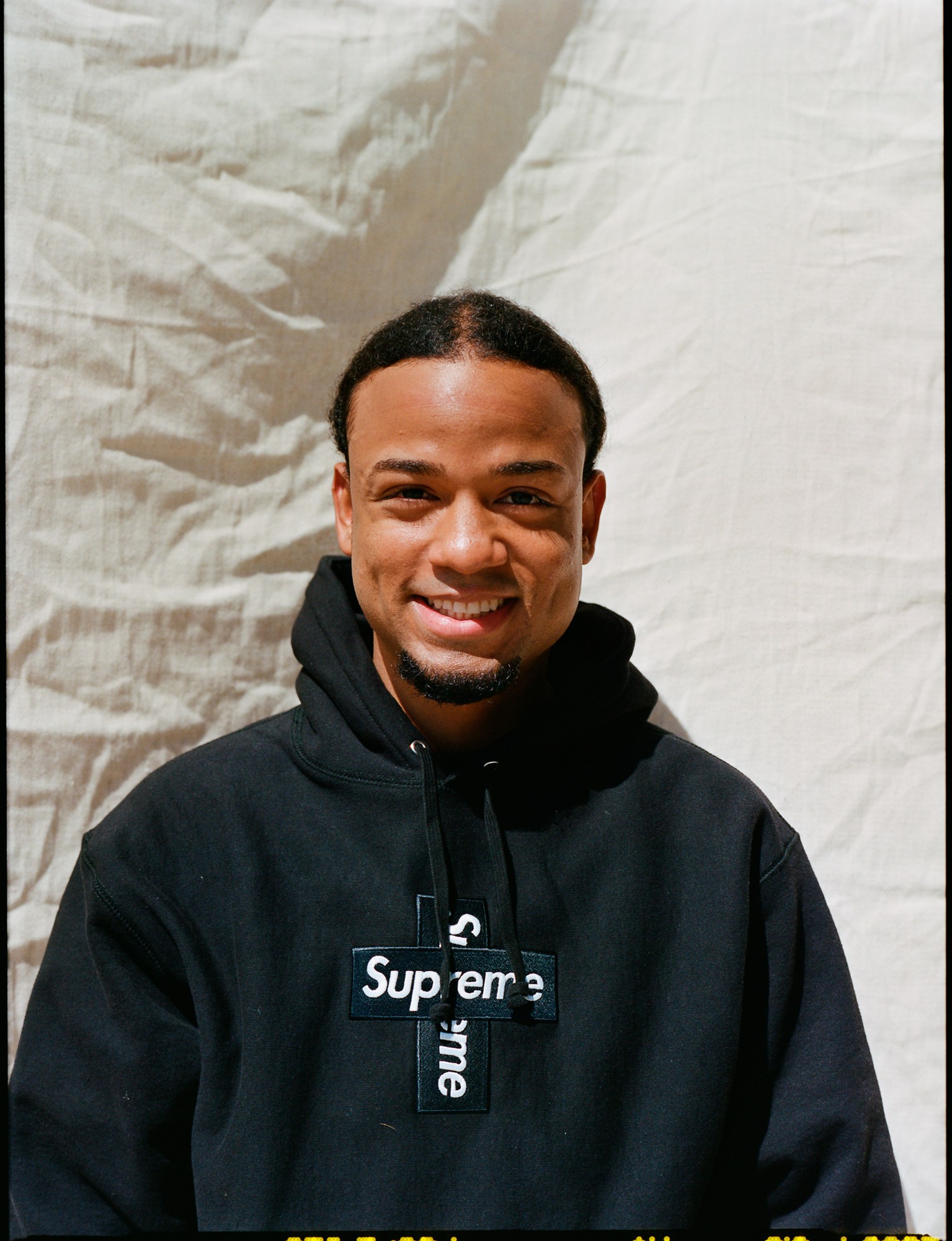

Damian Lopez Jr., another skater at the foundation, sipping a cappuccino in a thrashed pair of Air Jordan 1 “Royal Blues” resting on a Palace Chewy Cannon deck, tells me about growing up a skater in the Bronx. “Being in the hood, I used to be in the streets,” he said, “Kids would be calling me gay and stuff, and I was like this is fire because the girls are loving it.”

For so many kids, skateboarding became a means of escape from a home that didn’t accept riding this piece of wood, learning your city intimately, and exploring boundaries at the intersection of physiology, physics and simple bravado. “Honestly, that piece of wood kept me out of my neighbourhood,” Olu says. “Being a teenager, I was either gonna play ball in the hood, and then I’m going to stay in the hood, probably doing bullshit afterwards.” He paused to acknowledge a young skater trying to 50-50 a curb near our group, “Or I can get on a skateboard and learn something not everyone else is doing.”

“The Bronx, the fucked up part I live in, it’s just really messed up,” Damian says, before changing his tone to one with more histrionic heroism and continued, “I wanted skateboarding to take me out. I’m only 19. I’m trying to have my own crib or something so I can create, make music, make art.

Despite her roots in the most defining era of NYC skateboarding, Jessica left it behind in 1991 to pursue an education centred on mental health and psychology, culminating in a doctorate in counselling psychology. “By the time I returned to skateboarding in 2000, people were famous, too cool for school, and head-to-toe in Supreme.” Skateboarding was suddenly in the eye of the public; they were suddenly fashionable.

“In the hood, I saw mad guys and girls walking around with baggy pants,” Damian adds, “The skate fits I would wear in 2016-2017 when I was going to the flea market with my Dad to buy basic cargo pants.”

“Now people see Street League, and they see Nyjah Huston killing it making a pot of gold for himself,” Olu says. “So now the hood can see why you do it because you can get money.”

Despite skateboarding being in the Olympics, effectively solidifying the rebel pursuit as a mainstream sport, ultimately, a skater must still push through the city, do tricks on public property, in public spaces, and sometimes trespass private spaces, or as Damian describes it, “Fuck shit up”. “Skaters are the bad ones, out here doing bad stuff, you know, leather jackets and stuff,” he laughs, “But we’re not really doing the right thing because I’m skating past a street where people are trying to eat and they see it as someone making noise.”

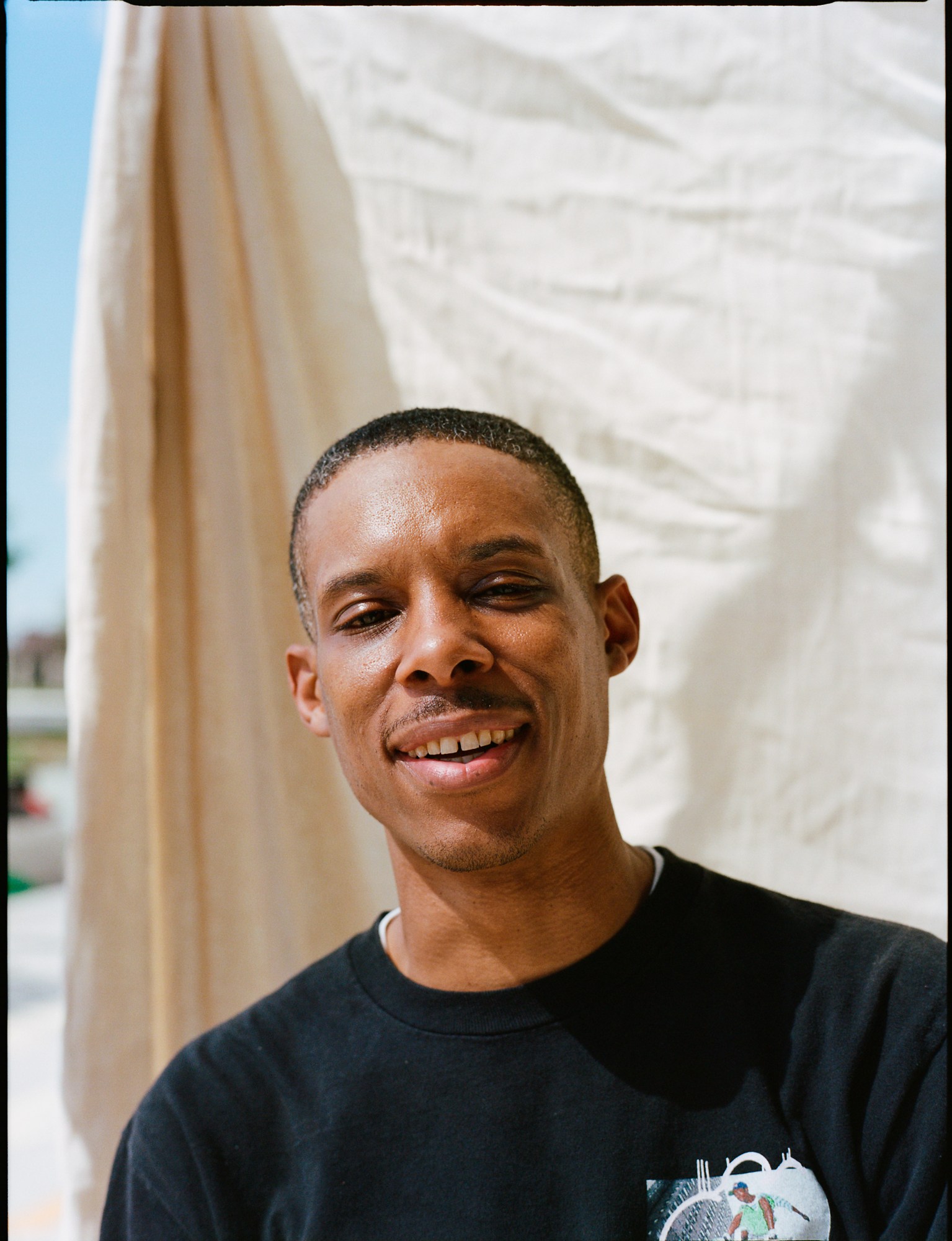

Greg Simmons, a Brooklyn artist and coach with Harold Hunter Foundation, reflects on the skaters he grew up with. “I know a whole bunch of the skaters from the 90s who were young and living the seven-day weekend just getting paid, but there was nothing in place to get them a job within the skate community. So they all fell off; some got addicted to drugs or stopped skating.”

This is where Jessica saw an opportunity. She recognised the idiosyncrasies of the skater’s character — the obsession over landing the trick by any means, and an incessant longing for the freedom afforded them by their skateboard — and looked to find ways to keep them skating while providing them sustainable opportunities to live, work, and flourish. In this, she found that the pursuit of work and education by normal means was particularly and uniquely difficult for many skaters. First, there were the demographics of the city’s skateboarding community and the neighbourhoods many skaters are from. “If you go to any gathering of skaters from all over New York and look around, you’ll see more black or brown skaters from the hood than anybody else,” Olu says.

The Harold Hunter Foundation became a space in the community for skaters to find positive uses for their energy, whether it be through mentoring other skateboarders, finding work within the industry, or finding ways to use their creativity to build a career in another field. Further, they were able to find opportunities in spaces and places that they wouldn’t otherwise feel they belonged because of, first and foremost, the colour of their skin.

Jessica understood the mind of a skateboarder and wanted to create “transformative spaces for educating” them. These were spaces of growth that worked dynamically with the way skaters move and think. “These were the spaces that skaters were not going to get by going to college or just being so cool on its own merit. These kids are really cool, but that alone doesn’t always get them through the door. Raw talent and creativity only went so far because so many circumstances pushed them outside the mainstream.”

The Harold Hunter Foundation brings together a community of skaters and professionals that provide resources to support the skating, of course, but also life and the ebbs of flows of navigating professional workspaces. Yet, significantly, they remain authentic to its unique culture. “We needed real ways to communicate,” Jessica says. “These are skateboarders in the street, after all.”

Therein is what makes the Harold Hunter Foundation so important. They are indeed taking so many NYC skaters and moving them into places that they either never knew existed or they felt they didn’t belong. Compared to the polished skating mecca of Southern California, I found the toughness and grittiness of skating in NYC beautiful and even romantic. There’s nothing like pushing through narrow, rough and tumble New York City streets from spot to spot. You have to be quick, smart and resilient. Because of this, all an NYC skater needs is a path to and through the door to do anything.

Or, as Olu put it, “If you know how to move around in New York, you know how to move around anywhere else in the world.”

Credits

Photography Ben Rayner