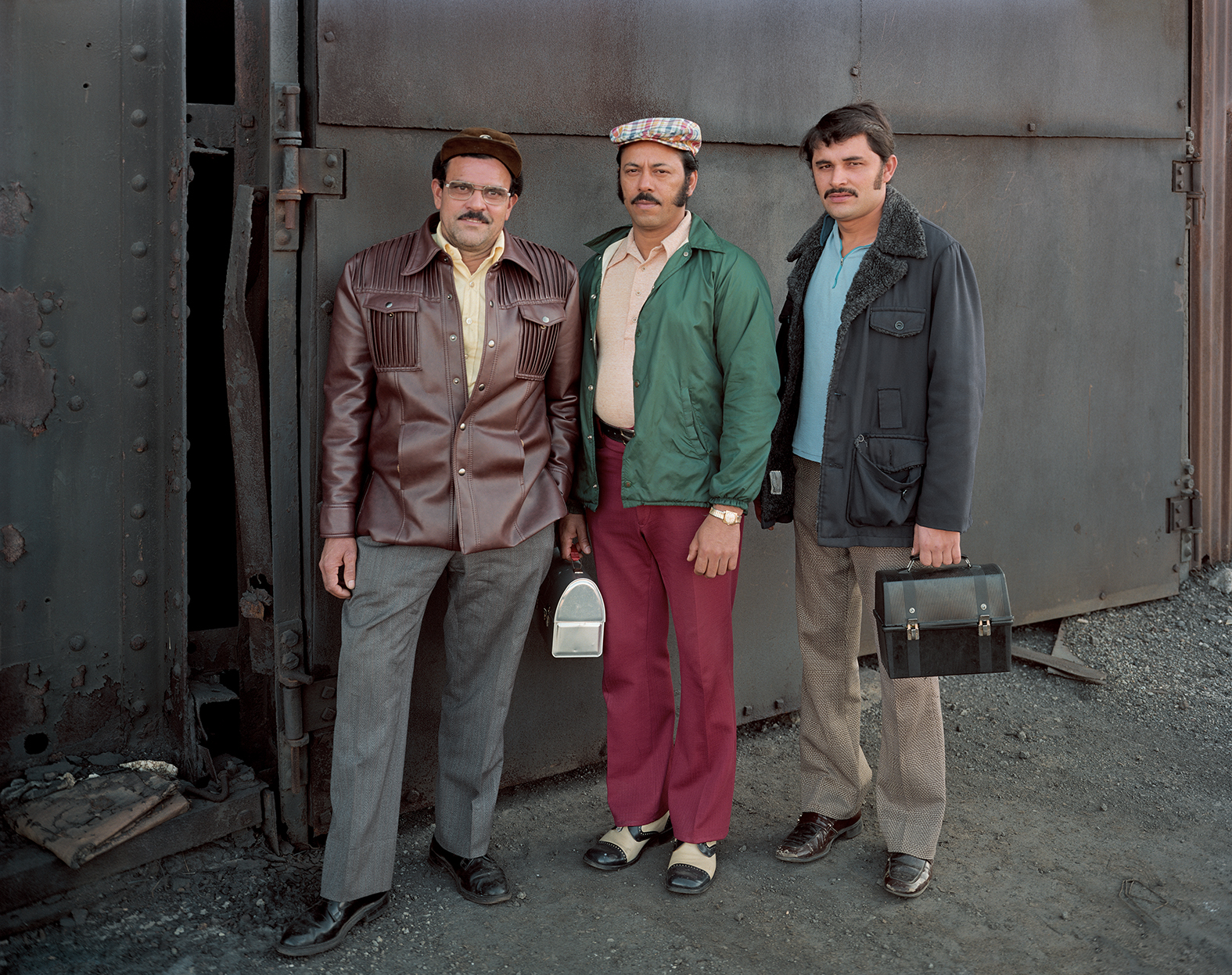

By 1977, the then 30-year-old Stephen Shore was already known for the pioneering colour photography of his American Surfaces series, in which he captured the banality of daily life with an eye so original that it helped to shape the modern practise. That summer, he went on assignment to Pennsylvania, Ohio and across New York state to photograph the towns and people affected by the massive layoffs taking place in steel manufacturing centres, as foreign competition and a drop in demand put a strain on the American industry.

A year earlier, the Bethlehem Steel company, a giant in the trade, started laying off thousands of workers in Lackawanna, New York and Johnstown, Ohio. These factory towns were built on the jobs provided by the steel mills, and by the late 70s they began to crumble. Unemployment became the status quo. The decades leading up to this decimation of livelihoods had largely been defined by a sense of booming industry, rising affluence, and the promise of a comfortable, if not easy, life for many Americans.

In Steel Town, Stephen Shore’s latest book release by Mack that brings together the images he took that summer, the sense of dispossession experienced in these towns is palpable. They reflect the rawness of a loss of personal agency, and the birth of the American Rust Belt. That summer, Stephen captured a moment in history that is still unfolding — as he says, “those jobs didn’t come back”. The political, economic and social ramifications are still shaping reality. We spoke to Stephen about how the series came about, and why he’s come back to it more than 40 years later.

You shot this series of images in the summer of 1977. I was wondering if you remember much about that summer — what the mood was like in the steel towns, and how you felt while you were there?

Would it help me to tell you how the whole project came about? So, it was commissioned by Fortune Magazine. And for decades, Fortune published once a month, but they had made a decision to be more timely and to publish every two weeks, and that the issues will be smaller. There had been a tradition, since the beginning of the magazine, of beautiful photographic portfolios. This was going to be the last time they had enough pages to devote to one. Walker Evans had been an editor there and was able to choose really whatever project he wanted. They wanted one last project, kind of in the tradition of Walker Evans, and asked me to do this. And that’s how it came about. So when I went, I had notes from a researcher who had been to these cities. I had contacts at the local steelworkers union.

I’m trying to see if I actually remember… You know, it’s so hard with photographs. I only am certain of a memory of something if I’ve never told anyone about that happening, or I’ve never taken a picture of it, because the stories that I’ve told the people, I think I’m remembering telling it, rather than the actual thing. But there are a couple of things that I’ve never told anyone, and I’m keeping them private. Because I know that’s an actual memory. So I’m not sure what I remember of the steel towns. Often when I’m working, I go, I just get into a state of work.

And what is that state of work like?

It changes at different times. I can step back and tell you what was going on in my mind at this time. For the previous four or five years, I’d been using a view camera and had been thinking very concretely about all the formal variables of photography and experimenting with them. And at this point, I felt like I had really begun to master them. This was the first time I did a project that was a kind of summation… summation isn’t exactly the word. I learned all these variables. Now I’m going to go to a project that’s driven by the content, these towns, the mills, the lives of the people, and I’m learning to trust what I’ve learned in the previous four or five years of experimentation. During those years I was also interested in the content, I was also interested in showing what America looked like at that time. But this was different. Because previously I also had these formal questions in my mind. This was now learning to trust what I had learned, what I had internalised.

This was an assignment rather than something that you had decided to focus on yourself, so did you approach it differently to something like American Surfaces?

Sort of yes and no. If they didn’t want work like my work, they would have hired someone else. They came to me, so they didn’t ask me to do anything that wasn’t out of my range. But also, it pushed my own boundaries. It forced me to do something that, by my own inclination, I wouldn’t have done, and it got me access to something that on my own, I wouldn’t have access to.

And so, while I had been dealing for several years with what American culture looked like in cities and towns, I’d never dealt with a kind of immediate crisis, something as temporal, in a way. This was the challenge for me. Because sometimes if someone is covering an immediate event, a crisis, the work can address it, it can be illustrative and not have a long shelf-life. In five years, in a year, it could have lost its meaning. But I’ve seen lots of other work that while dealing with something immediate where there’s a historical level, there’s also a kind of archetypal level, or a metaphorical level. And so an historical event can also be a metaphorical event, and affect people’s unconscious. So that’s sort of what I was looking for. I say ‘sort of’ because that kind of thing you can’t plan, you have to just be emotionally open to a situation and respond on lots of different levels inside, and hopefully that comes through in the pictures.

And, I mean… I can elaborate on this. The first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art was a man named Beaumont Newhall. He wrote a book called The History of Photography. In the last chapter he listed four trends: the document, the straight photograph, the formalist photograph, and the equivalent. The document is the picture that points to something in the world and says ‘pay attention to this’. The straight photograph is the self-conscious work of art that says ‘look at this piece of paper with this image on, pay attention to this’, the formalist photograph explores the formal nature of the medium or the structural qualities of the image. And the equivalent, he uses a term from Alfred Stieglitz, which is sort of a metaphorical unconscious emotional resonance of a picture. Okay. And the term I actually like — this is one that T.S. Eliot used in an essay talking about Hamlet — was “objective correlative”.

So something in the world is a correlative of a state of mind. And what struck me when I read Beaumont Newhall’s work was that, for me, the best photographs are all four. And that if a picture is only a document, and not any of the other four, it’s an illustration. But a lot of Walker Evans’ work and almost all of [James] Agee’s work is functioning on all these levels. In fact, the only time I ever heard Walker Evans speak in person, in the early 70s, what he was talking about was his pictures as transcendent documents, and he was specifically talking about them as equivalents. So that’s how he saw his own work. And so I had these thoughts in my head long before I did this project, and they were in my head before I began Uncommon Places.

That makes a lot of sense in terms of thinking about the images here as not just documenting the crisis, but as a larger exploration and something that continues to have resonance. These pictures are historical, but the story they tell is political, social, and continued on. They collapse into now. It’s kind of scary in terms of how close it feels.

I reviewed the whole work just before I had a retrospective at MoMA that opened in November of 2017. And I was thinking about the work just around the time of the opening, which was a year after Trump had been elected. It was exactly 40 years since the pictures were made. Places like Pennsylvania, where some of the pictures were made, which had been in presidential elections reliably Democratic states, had swung the election to Trump. And I realised that they were the children of these people who were doing this. I don’t mean to generalise, but the mills didn’t reopen. This became the rust belt.

I read the original article in Fortune, which talked about them the year before, in 1976, voting for Jimmy Carter, because they felt he was an outsider to Washington, and he was going to bring their jobs back. And then by now, a year later, they were disappointed the jobs hadn’t come back. And what the writer in 1977 couldn’t have known was that in three years, these people would become what were called the Reagan Democrats. Formerly Democratic voters who, for cultural reasons, voted for Reagan.

There is a health crisis there; a lot of that part of the country has an opioid epidemic. There was an amazing book written a few years ago called Deaths of Despair by two economists, Anne Case and her husband Angus Deaton, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics, examining the life expectancy of middle-aged white people in America, which is decreasing. And the largest causes of death are opioid overdose and liver disease. They call these deaths of despair, right. And while the jobs that people in my photographs had lost were hard work, they were productive. They made something. They had strong unions that got them good benefits. And because those jobs didn’t come back, their children are often working in the service industry and at a lower pay scale, and it’s not that kind of middle class productive work.

Again, it’s hard to generalise, and I’m sure there are many exceptions to what I’m saying. There are many causes, and it exists in parts of the country that weren’t affected by the steel mills. But something is going on in the country that’s leading to these deaths of despair, and that’s leading to the exacerbation of the cultural differences and the political divide.