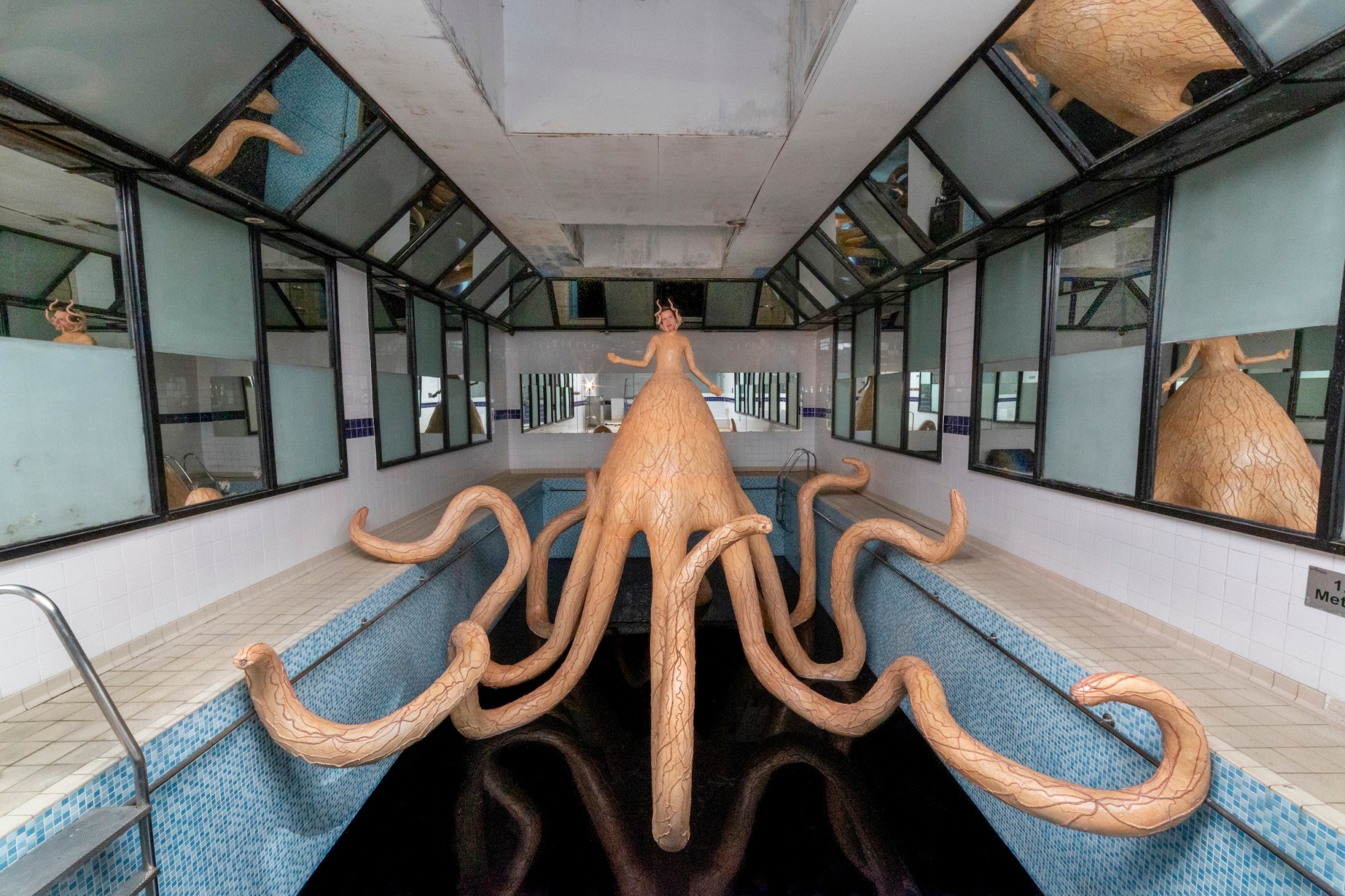

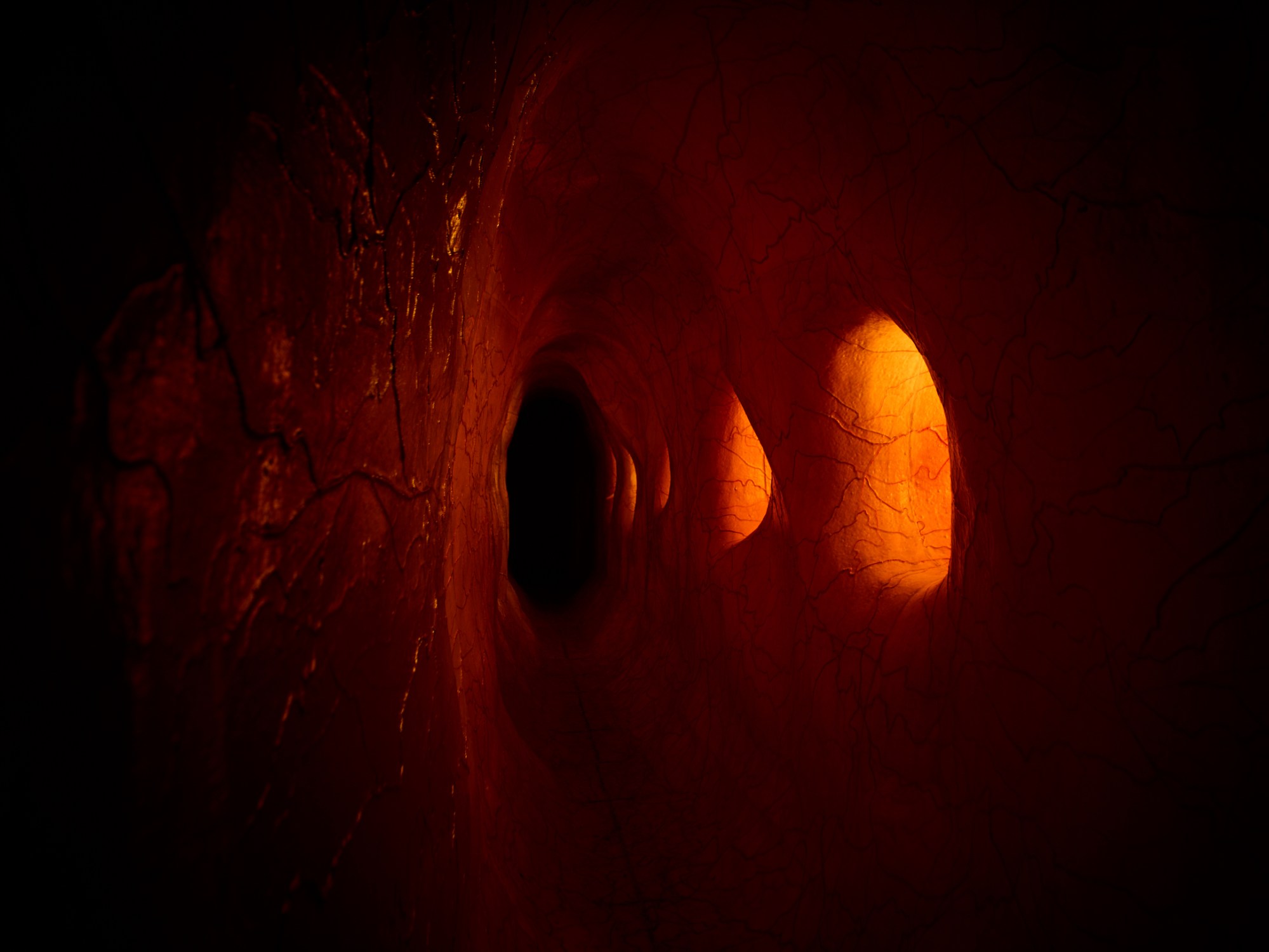

People across London are talking about a new installation inside an abandoned health centre on a leafy street in Belsize Park. As you enter Transgenesis, you descend into a dark tunnel — like crawling inside the densely packed linings of a bodily organ — only to arrive in a room lined with mirrors, where ceramic sculptures linger on spindly legs like jewel-coloured creatures recovered from the ocean’s depth. Further into the darkness, and we find the figure of Agnes? — the Italian artist and former Gucci model — immersed atop an octopus-like sculpture, unleashing an inhale-exhale siren song.

Presented by The Orange Garden, this is an installation that is increasingly hard to miss — featuring in countless stories and posts across Instagram since it opened last month — and it presents an intense moment of personal discovery and declaration for the artist at its heart. I meet Agnes? for breakfast a few minutes walk from the exhibition space, in the few hours she has each day before her performance begins again; a long-durational feat of eight hours a day for 23 days.

Over orange juice, she’s exhausted but bright. This ‘series of experiments’ — curated by Arturo Passacantando, Tommaso de Benedictis, and Charlie Mills in partnership with Harlesden High Street — began to take shape in August 2020, when Agnes? first encountered the cavernous space (one of the many unusual, unused commercial spaces where Harlesden High Street’s nomadic exhibition programme appears.) Practical work began in November from Agnes?’s studio in Italy, where the artist worked each day — with the help of friends — to produce such a physically monumental body of work in time.

The entire space triggers a sensorial engagement, from navigating the dimly-lit entrance tunnel, lined with foetus-like latex sculptures presented life-size in roundel forms, to the audio-visual entrancement of the work itself. In the chamber of ceramic sculptures, glimmering on metal fronds like jellyfish in the half-darkness, the floor is covered in white sand. “It was important to me to play with the space, to consider the actual space as a body in itself,” Agnes? says. I was creating a new body, but at the same time, I was presenting the space as a body. I like to consider the whole space as an extension of my body. As if the octopus is giving birth — is giving life — to everything else.”

For Agnes?, the ocean has always represented a state of flux and transformation. Her father was a sailor, and she grew up on a boat; when we meet for breakfast, I notice her hands are tattooed with an anchor and fish. She tells me of how her father threw her into the ocean as a child, of how “underwater was always a safe place, a place of comfort — for me it always brought me back to the womb of the mother. I always felt protected.” When Agnes? speaks of the sea, it seems interwoven with the underpinnings of this project — an externalisation of her own gender transition, which saw her begin taking hormones the day that she arrived in London. “Water has the great power of giving life and transformation, but also of destroying things. It’s such a powerful element.”

Amidst the underwater world of the exhibition — the subterranean darkness and fluid, fleshy folds of the womb-like installation — this notion of creation-destruction, fantasy and threat, is made manifest. “I’m giving birth to something new, but I’m also destroying something from my past. Transitioning itself, it’s a destruction. The hormones destroy part of you — you need to destroy part of your body to lead to new creations. The octopus does the same — it’s a creature that represents the great mother, the dedicated mother who, at the end of her life, dies for her offspring, letting her body be consumed.”

The earliest incarnation of Agnes? appeared five years ago, whilst the artist was studying at university. “I started talking about Agnes? five years ago, when I still had no idea who Agnes? was and what Agnes? meant to me.” Beginning hormones in conjunction with the exhibition’s opening, this project becomes an invocation — and externalisation — of the deeply personal process of becoming (and being). “My performance is real. The transformation is happening in front of you; it’s not just a theatrical representation.”

And just like that, Agnes? seems everywhere — in last week’s Time Out, in i-D, and on digital feeds over and over again. I ask how it feels to see this personal process play out so publicly, thinking of Felix Gonzalez Torres in the early 90s and his externalisation of his partner’s death from AIDS as a pile of sweets, which the viewers could take away with them. He wrote at the time of his desire to “control the pain” and yet found himself wanting to reclaim the sweets — to take it all back — as soon as he watched the public happily walking away with the artistic metaphor in their pockets.

Agnes? describes how “the desire of someone who would like to transition, and to transform, is to control — but you cannot control something that is uncontrollable. You never know what is going to happen with your body when you transition, and this performance was the same. I didn’t know what I was going through.” And yet, her primary concern with the exhibition going viral is that “this is a physical interaction” — not to be skipped IRL as a result of consuming it on Instagram. She adds: “My art and my life are interconnected — one informs the other. My artist side and my private side are unconsciously and unconditionally chained and fused.”

We get up to leave, and Agnes? is again en route to the exhibition space — ready to apply her mask and mic, to be covered in baby powder, and to ascend into the octopus via a ladder and trap door. I ask how it feels to look out from her vantage point, after months of so much work and amidst such a personal project. “It feels like an eternity. It feels like time never passes. I change a lot. Sometimes I’m sad, sometimes I cry, sometimes I’m happy, sometimes I laugh.” And yet, this project is an essential declaration and embodiment of everything Agnes? stands for at this time; “I’m transitioning, the work is a transition, the people who enter the space need to transition. It’s an invitation to open your mind.”