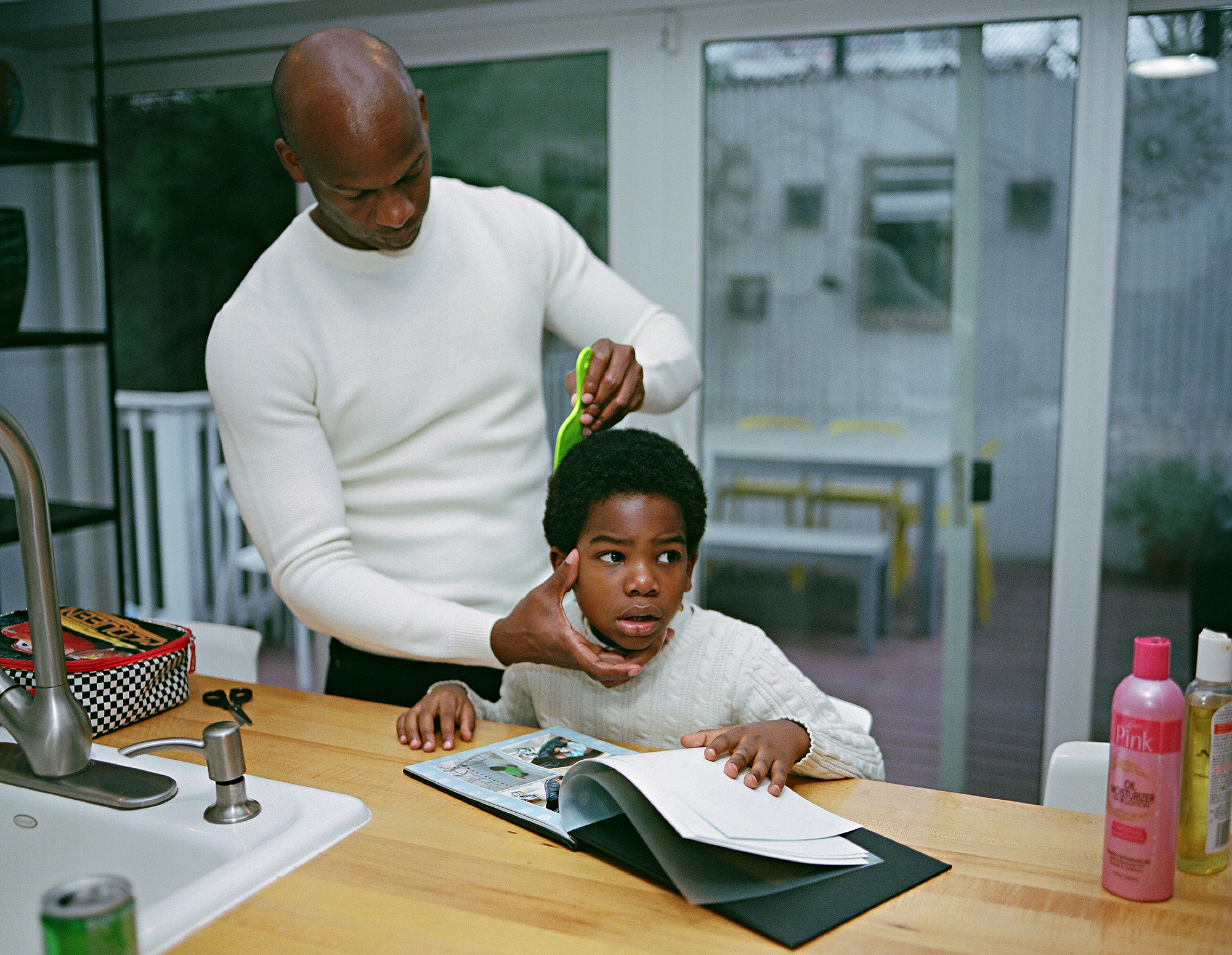

“What you see in the book is commitment and love between parents and children,” says Bart Heynen. For his latest monograph, simply titled Dads, the Belgian photographer travelled across the US cataloguing close to 50 families with gay fathers. Photographing men and their children – from young babies with dummies to 29-year-olds accompanied by fiancées – in spaces of their choosing, Bart sought to immortalise what gay fatherhood looks like today, following America’s milestone ruling in support of same-sex marriage in 2015.

Initially conceived as a personal challenge, having struggled to meet other gay dads following a move to New York and finding an absence of books that mirrored his own family, the project began for Bart in late 2016. “I was sitting with my interns watching Hillary Clinton’s concession speech the first day we started reaching out to gay parents,” he says. “I wanted to do this to meet other gay families; after all, we were all brought up by straight parents and so didn’t have the role models other parents have. I was brought up by a mother and father, [with] the typical roles given to them – my mother did the indoor housework, and my father took us to soccer. Suddenly I became a father, but at the same time, I was taking care of the kids in a different way than my father would have. I wanted to see how other families dealt with that.”

What he found as the project progressed was a complete rejection of the traditional gender roles performed in many two-parent heterosexual homes. “That was a major thing, that there is such equality in the division of labour,” he says, observing how the dads he met didn’t try and imitate straight parents, instead creating their own domestic frameworks. “Since they were not confined by their gender, I found that often these men interchange the labour in a very easy way. He can change the diapers, but he can also change the diapers; it’s not a problem because there are no gender divisions there. That I really love and I tried to highlight.”

Inserting himself into the daily lives of families in New York City and Utah, sometimes for a full day and other times for just a couple of hours, Bart would always chat on the phone before meeting everyone — not just with the dads, but also extended family members and occasionally their surrogates. “As soon as I come into their homes, I like to talk about myself and tell them what I have had to deal with, and in this case we had so many connections – I too have kids, twins; I worked with a surrogate, I worked with an egg donor – so we had similarities in creating our family and experiences that it was really easy to connect. I also gave them as little instructions as possible, which I think helped to get some kind of intimacy and be very open.” Additionally, and perhaps what most informed the trust between them, he promised to share the images ahead of publishing, offering to pull any pictures his subjects didn’t like (incidentally, no one took him up on it).

Primarily working with babies and young children – subjects for whom the camera was essentially just another game – elsewhere Bart photographed families with older children and occasionally adults; instances where, alongside their fathers, the background politics of the project were more explicitly understood. On one occasion, he shot a high school senior on the soccer field after practice, “while all the other parents and kids are still there – that was a very tense shoot because I felt like everybody was looking,” he says. “Everybody knew he had two dads, but it was never really mentioned, and now it was kind of formalised by standing there in front of a photographer. I felt the family were a bit uncomfortable. I was a little bit disappointed that we still have to deal with that, you know you still have to be ashamed. But it was also a masculine environment at a high school, so it was actually very nice for the guy, this 18-year-old, to have the courage to stand with his two dads and say, listen, I have two dads. It was a beautiful moment but at the same time frustrating.”

Primarily though, the project is a joyous celebration of gay fatherhood that unites a broad-ranging group of fathers in the US. Diverse in race, locale, income and convictions — and with varying routes to becoming dads — it paints an engaging visual study of one component of recent queer history. “We are pioneers after all,” says Bart, who, recognising the moment as a collective win, positioned the book initially as a visual tool for gay dads, current and prospective, and their children. “We have a responsibility. Since same-sex marriage became legal in the United States, you can really talk about a baby boom, there are so many new parents within the gay community, and we all have an obligation to share that with other people. In so many other countries, it’s still illegal, so it’s an obligation to ourselves, our kids, and also to future dads. We have a role to play.”

Increasingly he’s been considering the universal aspects of the work and, while keen to centre the men that helped make it, appreciates the unifying potential of a wider audience. “Regardless of your sexual orientation, it’s for people who are interested in families, who have a family, and just want to see how other families live their lives.” Produced under the working title Gay Dads, the book’s revised moniker — of Dads — is arguably more striking, simultaneously highlighting the similarities and differences framed within. It arrived at the suggestion of Bart’s publisher. “And I’m so happy he said that because that’s what we are, we’re dads.”

‘Dads’ is published by powerHouse Books out 15 June

Credits

All images from DADS by Bart Heynen, published by powerHouse Books.