For the last eight minutes, the aula magna lecture theatre has been silent — despite being filled with 200-plus students, who cram into any available seat or spot of carpet they can find. I’m at the sleek Manifattura Campus of Polimoda, the prestigious Florence fashion school run by Ferruccio Ferragamo, son of Salvatore Ferragamo. The quiet has been mandated by designer Francesco Risso, the creative director of Marni, who is holding court at the front without speaking a single word. He leans back in his chair, eyes closed, with a serene smile spread across his face. “Sometimes I like to sit or lay down and I try to go beyond the barrier of what I hear near me,” he tells me afterwards. “Suddenly, you discover new sounds. We don’t do much of that — stopping for one second, letting go and listening.”

Today’s lecture — a word Risso despises: ‘sermon’ might be more appropriate — entitled ‘The Process As Manifesto’ marks a homecoming for the designer, a full circle moment that arcs back to the very beginning of his career in fashion. Born in Sardinia, Risso moved from his childhood home of Genoa to Florence at the age of 16, and honed his design nous at Polimoda. He continued his studies at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology and Central Saint Martins before gaining almost a decade of experience at Prada, and stepped into his current role at Marni in 2016.

On this December afternoon, we’re speaking at the back of the lecture hall while students loiter nearby to thank him or snap a selfie. He graciously obliges, seeming to not mind the interruption. “It’s funny because I felt like I was walking into a new reality today,” he says of his return to his alma mater. “When I was at Polimoda it was a small, beautiful villa in another place. I missed out on an incredible evolution of the school. If you are open to learning, you can really push against the norms here.” Like many of his fellow students, his time here toed the line between working hard and playing hard. “There was an iconic club called Tenax, and at the time it was one of the best clubs in Italy,” he recalls. “I worked there on Saturdays, but it wasn’t really about working, it was all about the looks. The owner loved to have me around because I was way more daring than I am today. Polimoda brought this club kid dynamic and allowed for all these fun times to happen.”

Risso’s visit is the latest step on the designer’s two-year pilgrimage to fashion institutions around the world, from the Royal Academy of Antwerp to the Pratt Institute. His aim, he tells me, is to demystify what really goes into running a luxury house. It’s an ethos that aligns the vision of Massimiliano Giornetti, who has been the director of the school since 2021, drawing on 12 years of experience as creative director at Salvatore Ferragamo. “Everybody has a different approach, so my priority is not teaching one precise method of research and development,” Giornetti says after Risso’s lecture. “That’s why every year we attract different professors and designers like Peter Pilotto, and go into associations like the United Nations. I think it’s very important for the students to have a window into reality.”

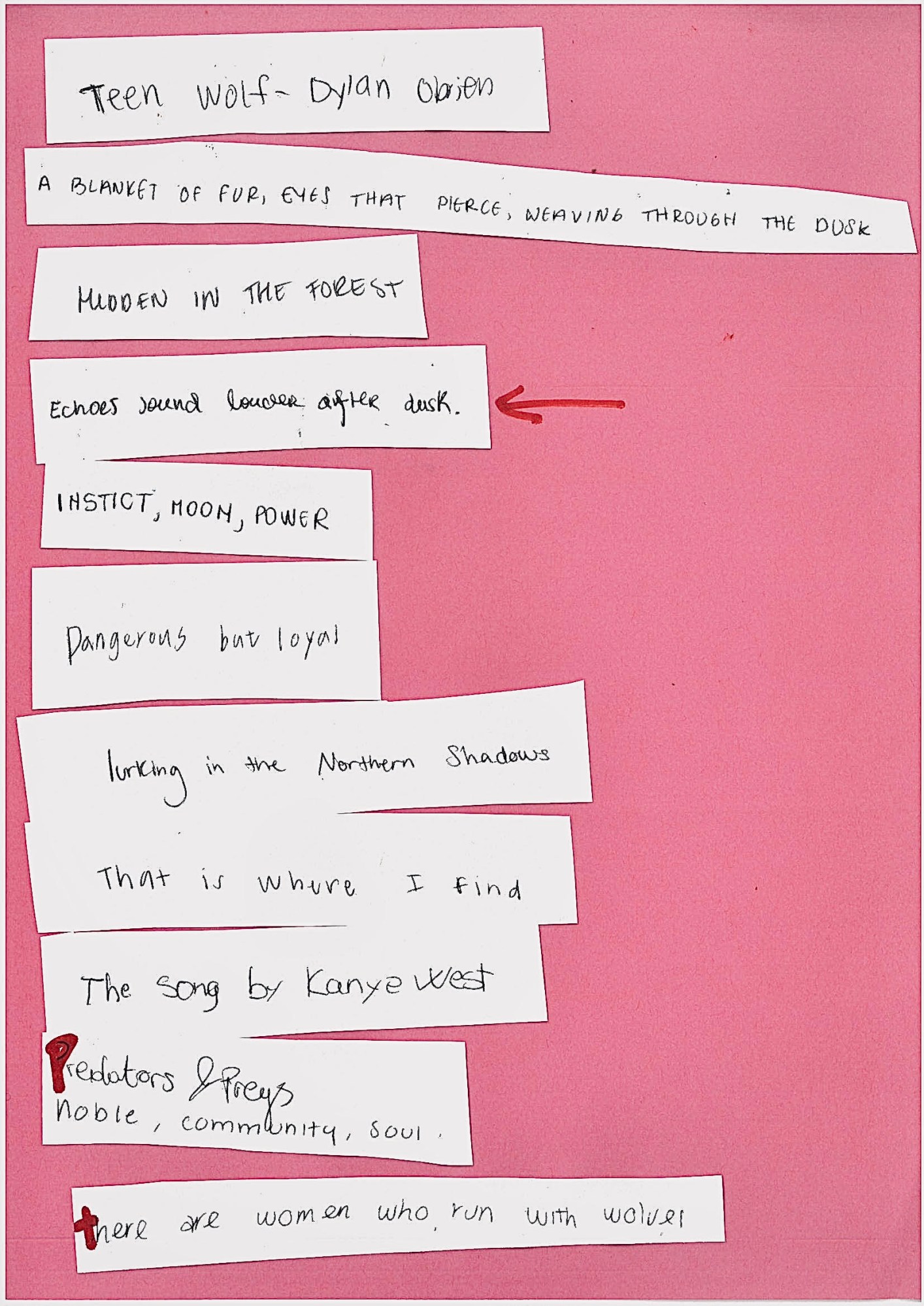

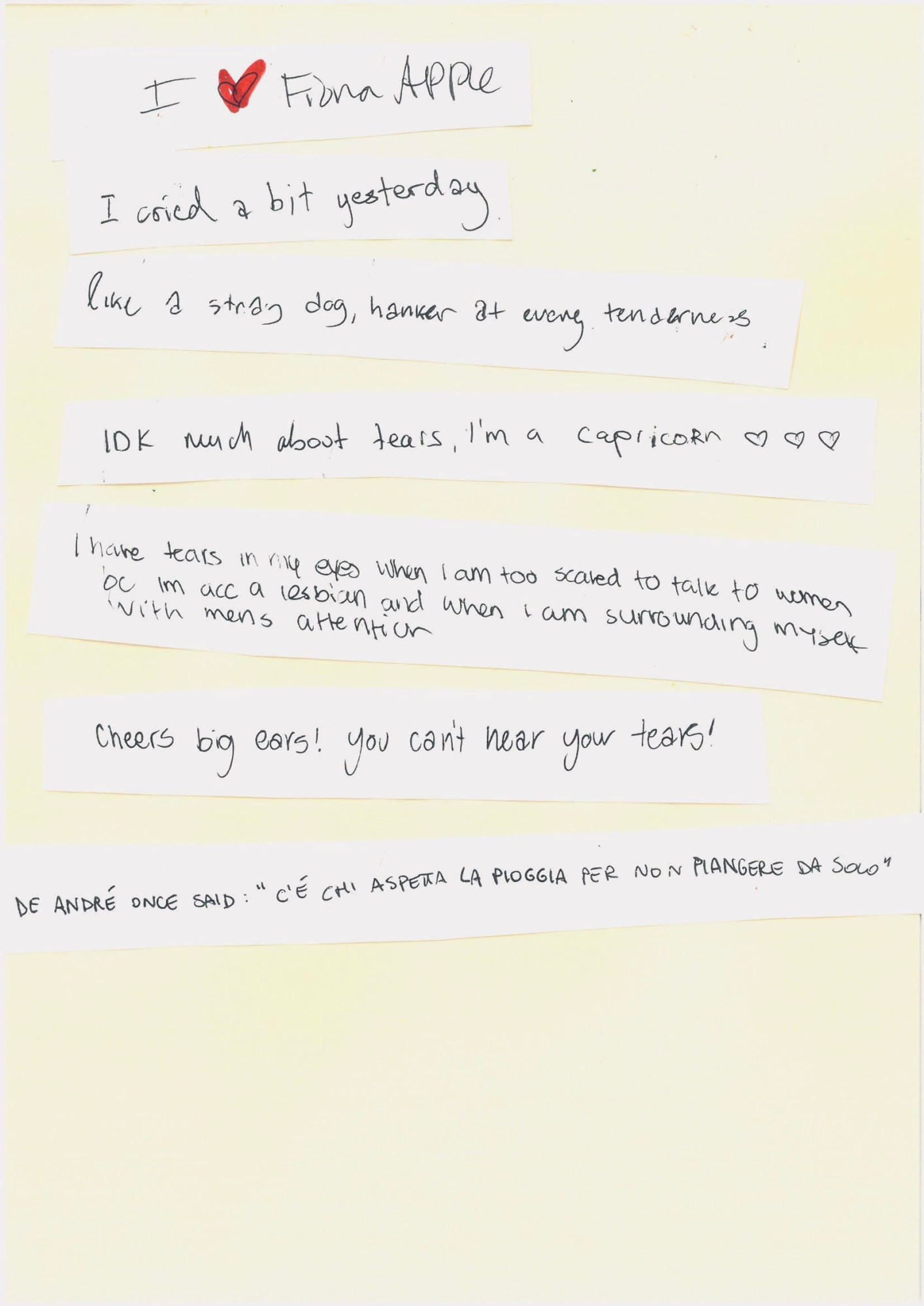

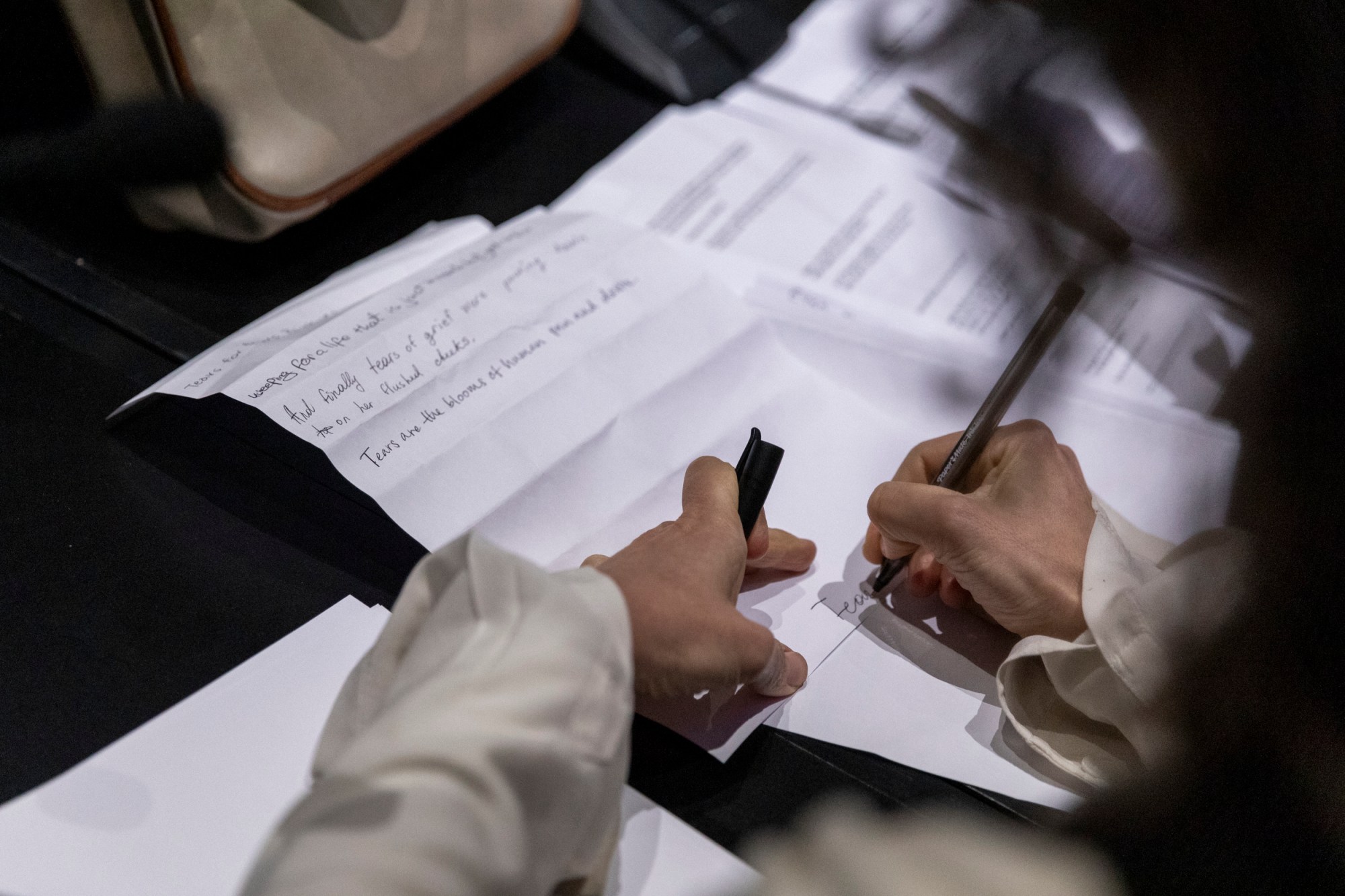

Back in the lecture hall, and with the silence broken, Risso’s session moves on to its next stage. The room is divided into three groups — ‘tears,’ ‘tulips’ and ‘wolves’ — for a game of exquisite corpse. Each person is instructed to write down a word, phrase or idea related to their group, before folding the paper to obscure their offering and passing it to the next person. Immediately a creative cacophony erupts. The concertinaed sheets are read out in an amalgamation of jokes (“That song by Kanye West”), dictionary definitions and short poems (“Tears are the blooms of human pain and death”).

After the activity, Risso explains its rationale. “Often I have found myself in moments in which creating might feel challenging,” he says. “There are so many ways to get out of it without thinking,” he shares. A year ago, he found himself at a similar impasse at Marni. The solution? What he refers to as ‘The Cave.’ “We banned images and wrapped our entire office in white paper to lose every reference of what it used to be,” he says. And he means everything: walls, windows, chairs, computers, stationery, you get the idea. “What came out was an incredible instinct that was way more alive because we were just there making together with our hands. We have to learn by the book, but sometimes it’s okay to break our own methods in order to find something better. It was really surprising how we discovered things through limiting ourselves.” The creative recalibration was replicated as the set of the AW24 show in February, with models meandering among crumpled white walls in the tunnels beneath Milan’s Stazione Centrale.

Before you reach for a stack of A4 to envelop your own dwelling, it should be noted that the task speaks to Risso’s specific vision for Marni, which he describes as “colours outside of the lines.” So, whether that’s plastering the walls with paper or sitting in silence for extended periods of time, find your own way of subverting the creative process to expand your point of view. “Instinct is a big part of what we do,” he says. “Not judging the ideas we have, but exploring them. Getting your hands dirty and not thinking about what’s going to be the end product. I like to call it training because we are all equal in that moment, trying to learn more, as you do here at school.”

The process is a direct result of the soul-shifting events of 2020, a transformative period for Risso. “I spent all my time painting. I painted my house from the curtains to the floors to the walls,” he recalls of his time spent in Milan, isolated from his design team. “When we finally met, we all shared these things that we made and spent 20 days dressed in overalls painting together. It was such a shift.” The ethos of colouring outside the lines courses through Marni’s recent outings. For SS22, the team oversaw 700 fittings pre-show with each attendee, creating custom, hand-painted looks with bright watercolour stripes and cute daisies — keepsakes representing the joy that has been missing from fashion amid quiet luxury and stagnation.

“Instinct is a big part of what we do. Getting your hands dirty and not thinking about the end product”

Francesco Risso

At the close of his sermon, it’s the students’ turn to pick Risso’s brain. Their questions highlight their fears for entering the industry during a particularly turbulent time. Navigating incisive questions around AI, sustainability and avoiding burnout, the designer assuages their various concerns while adding a few whimsical anecdotes of his own. “I started cello five years ago and all my musician friends said I was fucking crazy because it’s one of the most difficult instruments you can learn,” he says, of how he spends his precious downtime. “Sometimes I want to smash it on my teacher’s head, but the more I’ve started to understand it, it has brought a sense of rhythm to my work.”

One question in particular — about knowing when you’ve reached creative crescendo — was answered earlier in the talk. It’s a pertinent piece of advice for creatives at any stage of their career. “I love to learn,” Risso said. “I don’t think, ‘I’m such a great designer, I can design every Marni collection.’ What gives me passion is the process. Maybe one season I want to learn the same codes through painting, or I want to learn them through a shadow, or through hammering it on a wall. That’s what drives me.”

Credits

Photography by Serena Gallorini

Written by Dominic Cadogan