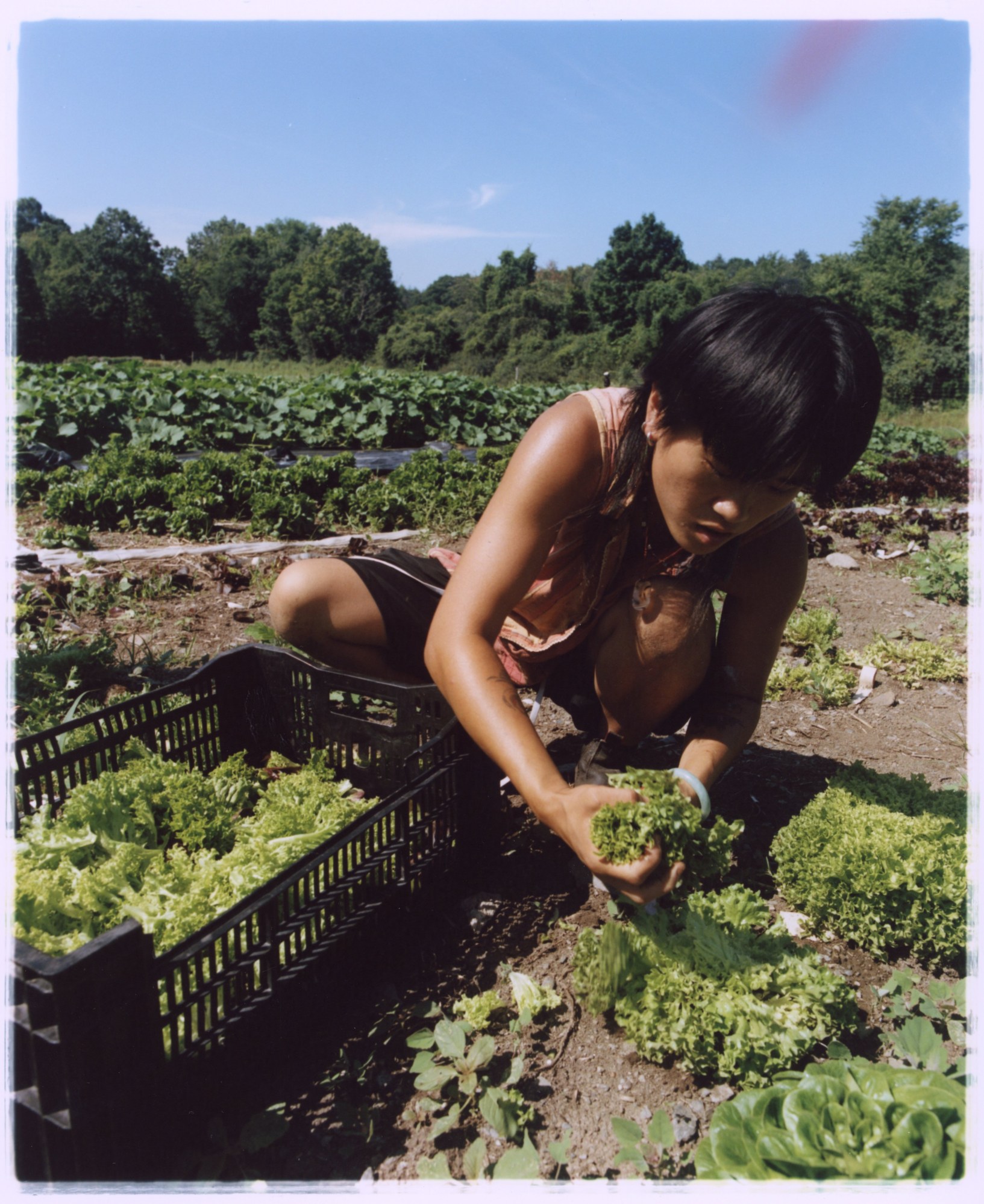

It’s a brisk November morning at Gentle Time Farm, and the growing season is coming to a rest. “We’ve put pretty much everything to bed,” says 28-year-old Kaija Xiao, pointing across the two-acre field in Chatham, New York. Long billowing tarps are held down by cinder blocks to protect the soil during the dormant months. In 2022, Xiao and partner Salt Wang founded Gentle Time as a trans and queer cooperatively-run farm that puts care for the land and people at its core. Resting the soil is a timely reminder for the farmers to slow down, too. “There’s so much to do and so many things to care about,” says 27-year-old Wang. “It’s hard to remember to care about yourself first so you can continue.”

A cold wind tousles the leafy rows of celtuce in the field, and under the arched frame of a high tunnel, rosettes of emerald tatsoi (a bok choy relative) wait to be picked. In the coming days, the remaining harvest will be distributed to low-income east Asian seniors by Heart of Dinner, a mutual aid group started at the onset of the pandemic to address food insecurity and loneliness among New York’s aging east Asian communities. Gentle Time’s vegetables are tucked into care packages with groceries and hand-written messages that Heart of Dinner brings to elderly east Asians across Chinatown, Flushing and in East Harlem, where many seniors have been displaced by gentrification and struggle to find culturally relevant foods.

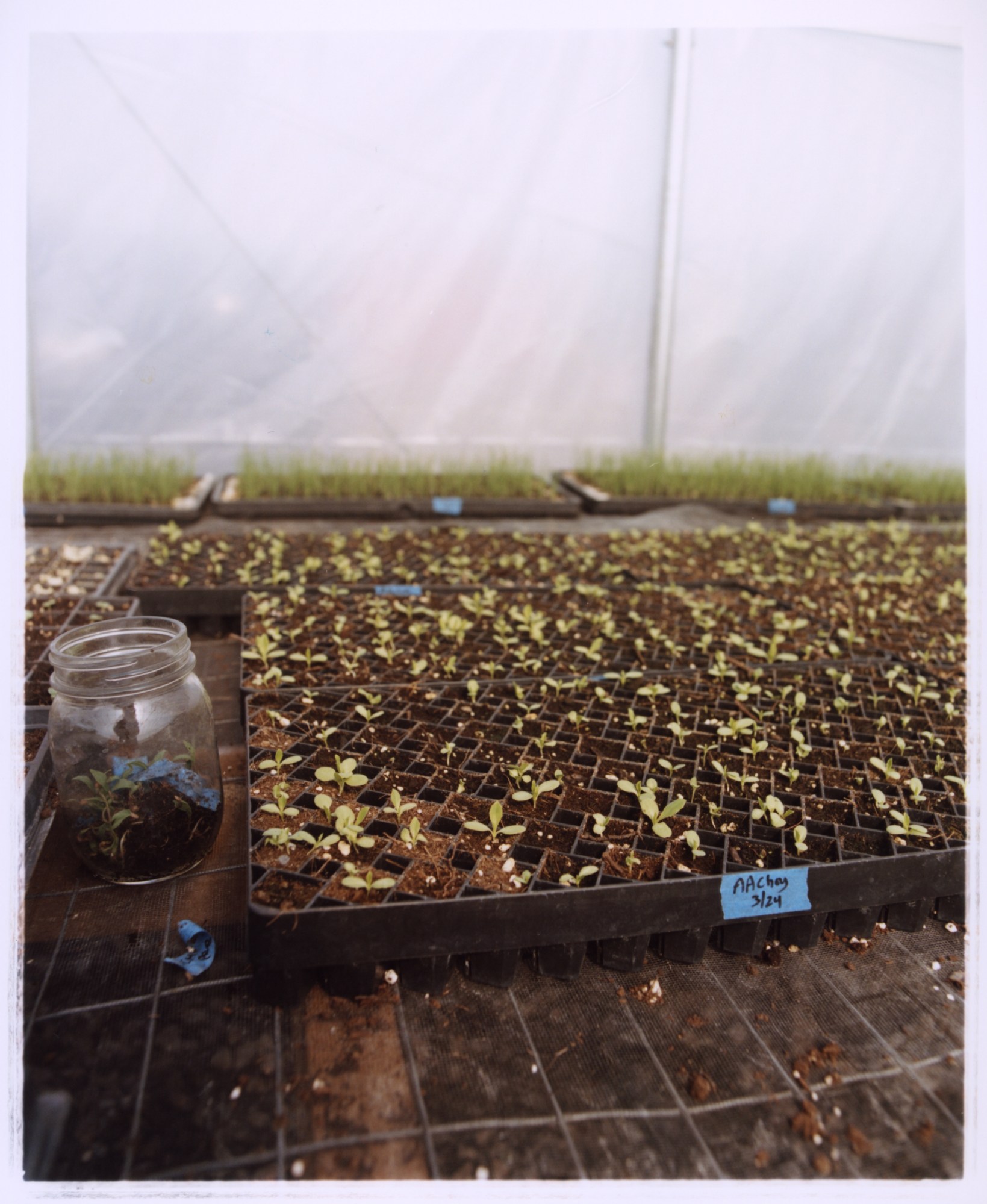

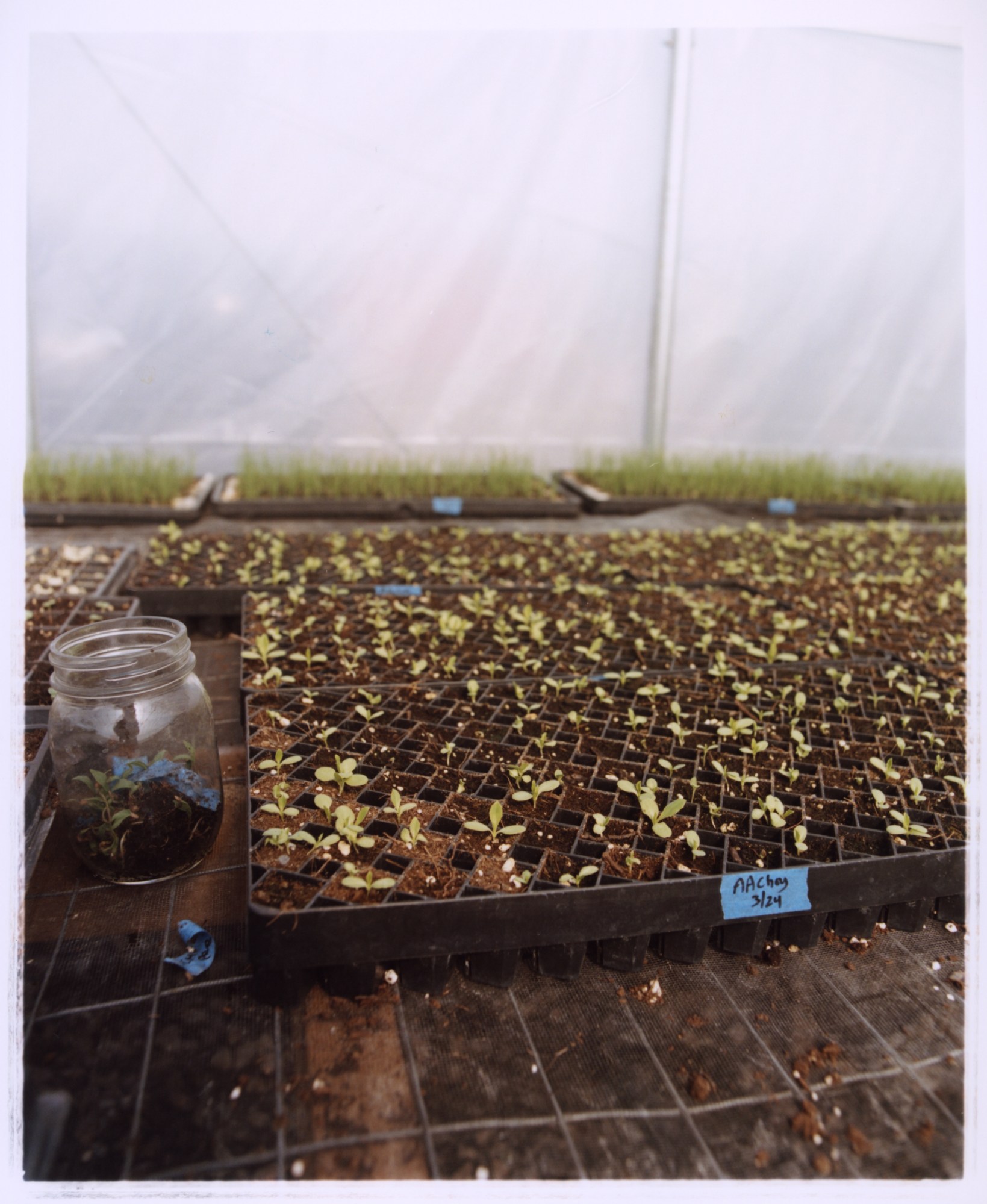

Gentle Time works to preserve the cultural memories of New York’s Asian diaspora, a community that faces rising rates of food insecurity, and to adapt regenerative growing methods in a changing climate. They compost, aerate the soil without tilling, save seeds for the coming season, and document much of it on their TikTok, t4tfarmtime. “Seed saving is not only about the actual seed but it’s also about saving the memory of how it’s supposed to taste for community,” Xiao points out. “These crops have shaped our lineages for generations. We’re not just growing bok choy for eating it — plants need us to keep their lineage going, too.”

Xiao and Wang followed similar trajectories from their home city of Palo Alto to New York, each making a pit stop to work at Fiddlehead Farm run by two lesbians outside of Portland, Oregon. It was an early snapshot of what queer farming life could be like. In 2021, Xiao conceived the idea for Gentle Time and drafted the field plan, planted the first cover crops, and within the following year, Wang moved upstate to join her. Together, they became a worker-owned cooperative and received a loan from Co-op Hudson Valley to start growing.

It’s hard to imagine their field, now organized into neat rows of diversified vegetables, was once a wild brush pile where cattle grazed. “Everything is super tight,” explains Wang of the farm’s leased land. “All of our inputs into the soil and all of our spacing for crops has this underlying preoccupation with running out of space.” Their block system is based on high-density farming methods they learned at Brooklyn Grange, a five-acre rooftop farm where Xiao farmed and Wang taught ecology before leaving the city.

“These crops have shaped us for generations. They need us to keep their lineage going too”

Kaija Xiao, gentle time farm

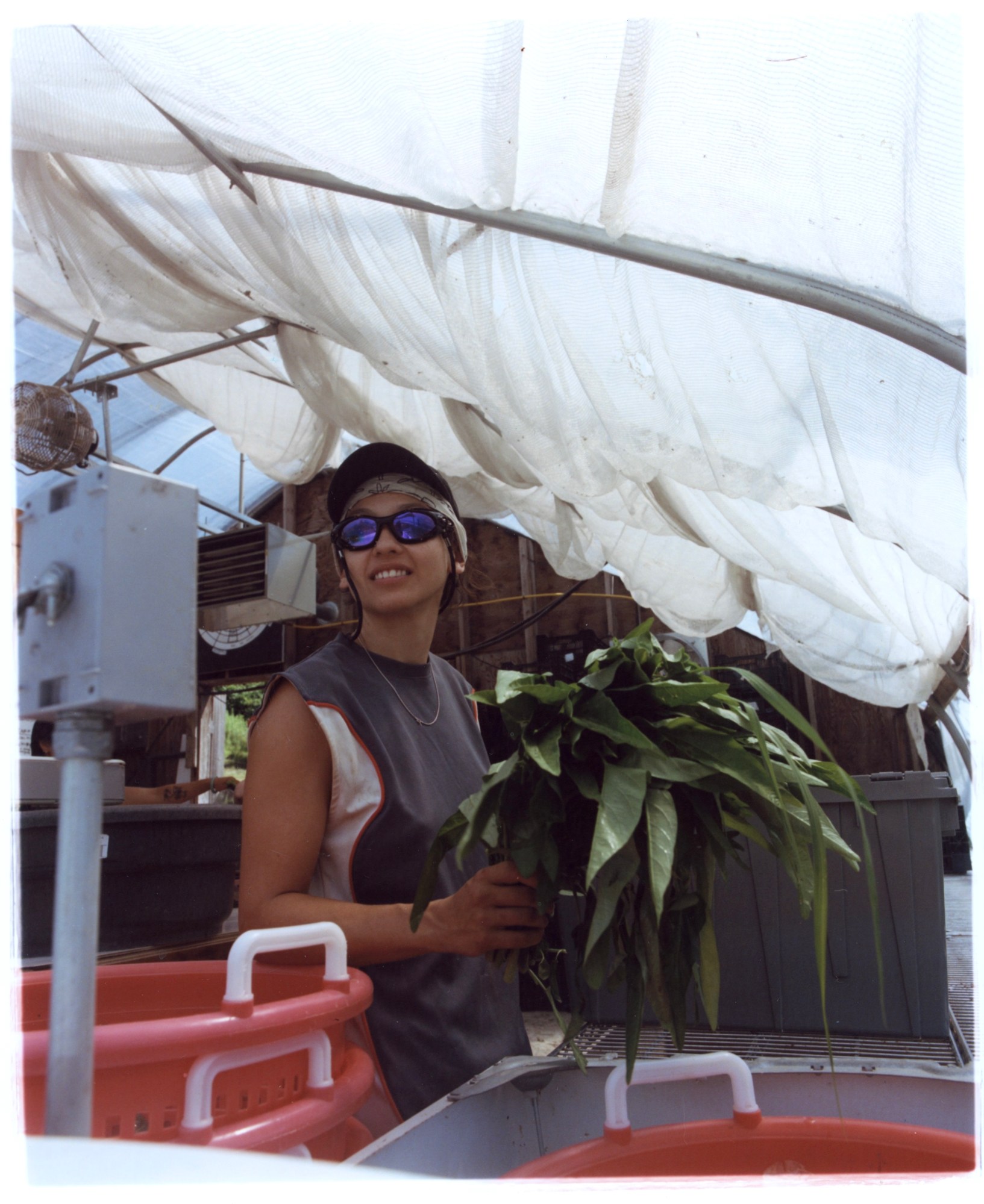

In 2023, Gentle Time joined Choy Commons, a nonhierarchical cooperative of New York farms. The group also includes Christina Chan of Choy Division, a nearly four-acre farm located at the Chester Agricultural Center, and Amanda Wong of Star Route Farm, a four-acre farm that’s part of the Catskills Agrarian Alliance. The three Asian-led farms are separated by roughly one hundred miles and operate as independent businesses, yet they work cooperatively to pool resources, scale up operations, and sustain each other through uncertain futures with a dogged sense of humor. “Polyamory but it’s because you need 3 farm incomes to survive now,” reads a meme they made to promote the cooperative’s wholesale program.

Choy Commons is building their own distribution chain to strengthen the link from their farms to mutual aid groups, community supported agriculture (CSA) programs and local restaurants across New York. Together, the farms have been able feed hundreds of families each week, a testament to their meticulous crop planning, troubleshooting, and hard manual labor. It’s a rigorous schedule, but the young farmers find levity in their day-to-day work by singing to curly bundles of garlic scapes, stimming on the broadfork (a tool that aerates soil) and, on occasion, meowing in a field of carrots.

Farming at the margins can be lonely. Part of what spurred the farms to organize as a collective is a desire for closer-knit community in a somewhat isolated industry. “We wanted to build systems that sustain all of our farming efforts because we recognize we’re all doing very similar things with similar missions, so how can we support each other?” says Christina Chan. “Even just talking to each other through the season is great for morale, and we can share advice on how to grow things.”

Chan, a 36-year-old native New Yorker, started Choy Division out of a backyard garden in Astoria, Queens in 2019. After studying environmental science, she was drawn to farming for the opportunity to work outdoors and “create spaces for animals and plants to flourish,” she says. In 2020, she relocated to the Black Dirt region of Orange County, sixty miles northwest of New York City. The area was once a densely-vegetated marshland before it was drained in the late 1800s, revealing uniquely rich organic soil that’s ideal for farming. Choy Division holds a thirty year lease through the Chester Agricultural Center, a sprawling compound that provides farmers with infrastructure like large storage sheds, walk-in refrigeration, and farm equipment, some of which is used communally. Chan shares ownership of a tractor with three other small-scale farmers.

Farmer networks, small grants and apprenticeship programs have been make-or-break for Chan’s career in farming. She first apprenticed under Asian farmers: Kristyn Leach of Second Generation Seeds, who showed her the ropes of operating a farm business, and then with Larry Tse of DIG Acres, who helped her carve out a niche path as a young queer Asian farmer in a predominantly white industry. Tse was instrumental in helping Chan find specific Asian vegetable varieties to grow, “even if there weren’t a lot of English language resources on how to grow the crop,” says Chan. “He would know what is the culinary profile I should be looking for, or what are the dimensions people at the grocery store want.”

Tse affirmed Chan’s conviction to prioritize vegetables that are meaningful to the Asian diaspora, even if they are uncommonly grown in the Hudson River Valley. “If we could find the variety and get the seeds, he would help me troubleshoot it without me having to explain every single part of what I’m trying to achieve with this crop. That was invaluable,” she smiles. Programs like Glynwood’s Farm Business incubator and Hudson Valley Farm Apprenticeship provided the tools for Chan to find crew members and run a business, and she draws off-farm income as Glynwood’s Farmer Training Program Coordinator.

The farm is more than a site to grow food. It also functions as a green space where people who are fed by Choy Commons’ crops can visit. Chan arranges seasonal farm trips with Asian Americans for Equity, which runs a subsidized CSA program with Choy Commons and provides transportation for Asian seniors to and from the farms. During the busy season, volunteers help Chan’s farm crew with fieldwork like weeding radishes, planting garlic, and harvesting a bumper crop of sweet potatoes. In return, the experience “gives members of the Asian diaspora a chance to be with the land, work the land, maybe see if they’re interested in agriculture,” Chan explains. These gatherings are made more meaningful because “there aren’t a lot of safe spaces to explore [farming] as a person of color or anybody from marginalized backgrounds. There are just very, very few places you can go.”

“Western companies want everything to be mild. I want it to be strong and spicy”

Christina Chan, choy division

Less than one percent of farmers in the U.S. are Asian, a statistic that bears the violent marks of the Chinese Exclusion Act, an 1882 law that banned Chinese immigration to the U.S., and the California Alien Land Law, a 1913 law that prevented immigrants and their children from owning land, and targeted Chinese and Japanese farmers. These laws fed the flames of violent anti-Asian sentiment and led to the subsequent mass displacement of Asian communities who were forced off their lands. The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn’t repealed until 1943, and the California Alien Land Law remained in law until 1956.

Histories of discrimination linger long after laws are rewritten and can be perpetuated in something as seemingly arbitrary as a seed catalog. Chan observes that U.S. seed companies’ Asian seed varieties often lack botanical specificity, or the pungency is bred out to appease a colonial palate that values tame monocrops over unruly biodiversity. “Western seed companies seem to want everything to be very sweet and very mild. But for the Asian palate, and honestly for a lot of the world, we want bitter, we want sour. If it’s mustard greens, I want it to be strong and spicy, not taste like crunchier lettuce” she says. “The flavor is not developed with the culture in mind.”

Chan hones in on the characteristics of each plant she grows to preserve both the cultural memory of how food tastes and the cultural practice of showing love. Feeding someone is the primary way you show care for them in Chinese culture, Chan continues. “Instead of telling someone, ‘I love you,’ we ask them, ‘Have you eaten?’ And while I’m not directly cooking you a meal, I’m growing you the food that feeds you,” she remarks. “The farm is very much my heart outside of my body.” As a business model and an identity project, growing the same crops that her ancestors ate is a practice that has deepened Chan’s connections with others in the Asian diaspora because “it’s made me more confident of a person, more proud to be who I am, more connected to my culture.”

Sunlight wanes over the treetops surrounding Choy Division’s field as Chan leads the way through harvested rows of scallions, daikon, sweet potatoes, Korean mu radish, and cilantro, “which is apparently invincible,” she laughs, applauding the herb’s hardiness. In two weeks, her last wholesale delivery will go out, culminating what was a fruitful year for most of her crops. “Our turnips didn’t do as well,” she quickly adds. “They had a lot of disease.”

She pulls out a small knife from the side pocket of her work pants to harvest a Taiwanese flat cabbage. The cruciferous vegetable is having a moment on social media after chef Eric Sze documented a recent trip to Choy Division where he compared cross sections of a conventional grocery store cabbage with the sweeter and more verdant one he harvested in Chan’s field. “Finally,” Sze says, “we can have cabbage like we do in Taiwan.”

On the walk back to the sheds, Momo, her farm dog, kicks up loose dirt as fine as soot. It hasn’t rained in weeks, and gusts of wind threaten to erode the soil. Farmers in the region have been hit by drought, wildfire smoke that blocked the sun during the cool months, followed by flooding that can quickly turn the fields back into wetlands. The uncertain conditions of climate collapse are exhausting, but Chan greets the unknown with persistence. “It’s not a job, it’s a full-on lifestyle, and you never really know what’s gonna happen at any given point, so you just have to be prepared,” she concludes. “All I’m thinking about is what do I have to do next? Is this thing going to survive the frost? Did I leave the irrigation on?” The hardest part of farming, she sighs, is that there is no off switch.

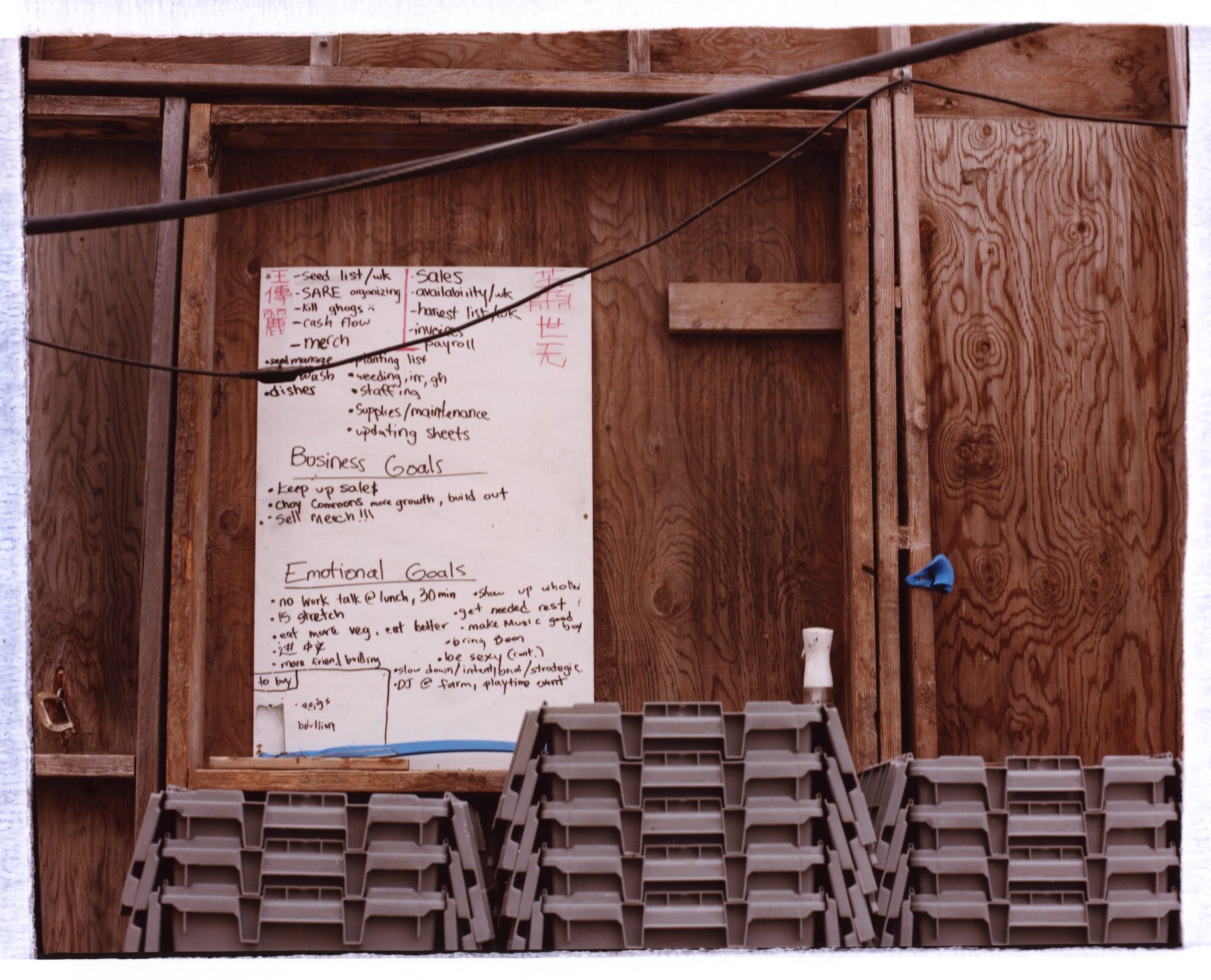

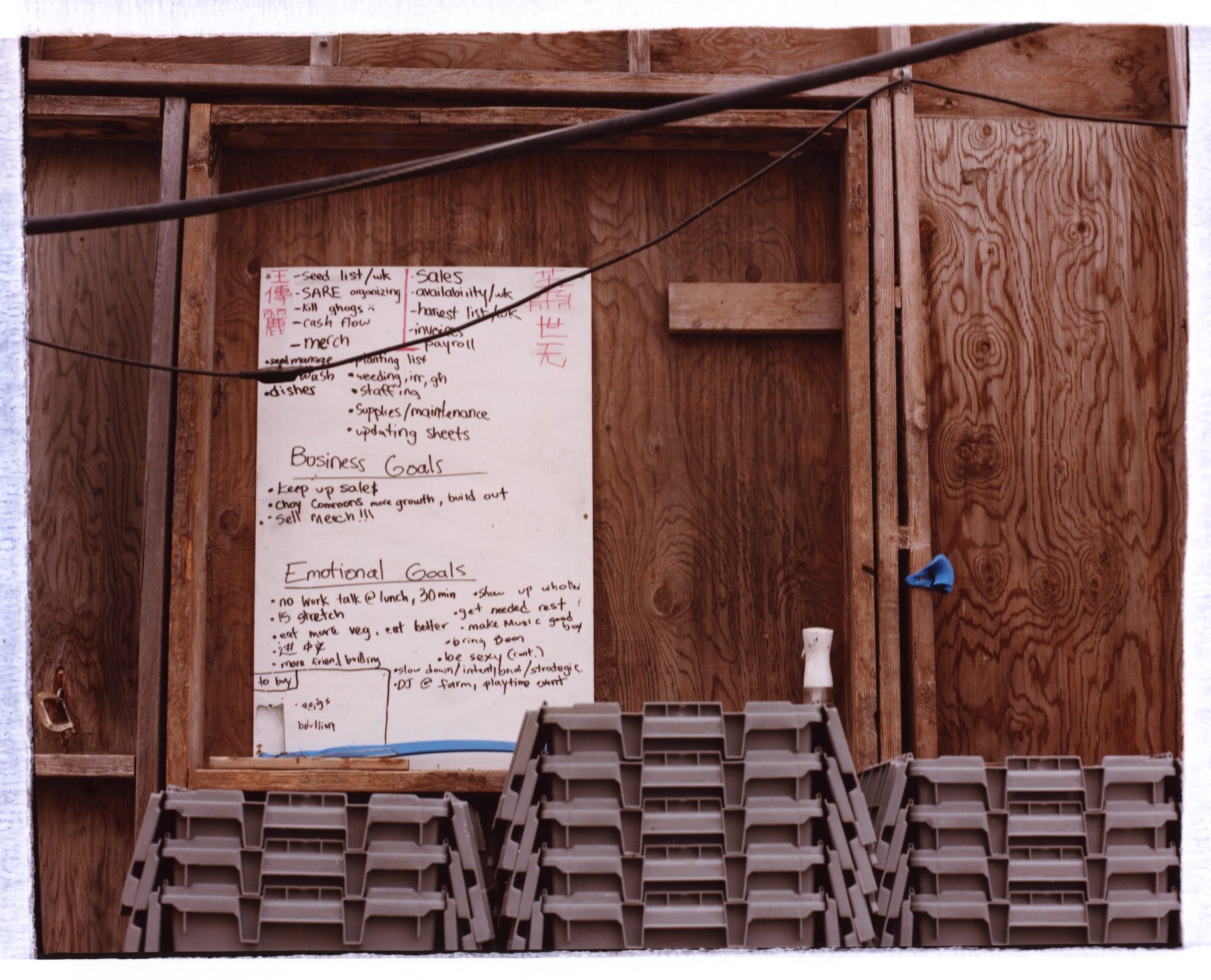

Planning the seeds of the future is a worthwhile gamble. Last year, Xiao and Wang transplanted 40,000 seedlings by hand: Chinese broccoli, Taiwanese lettuce, kabocha squash and long beans, among others. The irony of farm life is being surrounded by vegetables but being too tired to cook anything. Some days, to save time, they would split a bowl of instant ramen for lunch and work until dark. But this year, hiring a full-time employee has radically changed their perspective on farm labor and how to recondition themselves against burnout.

Instead of twelve hour days, they work nine. Instead of skipping meals, they go out to eat if they don’t have energy to cook. “We don’t want to perpetuate fucked up shit,” says Xiao on the unforgiving working conditions. “But it’s easier to be conscious of that to another person than to yourself.”

In August, Wang suffered a concussion while harvesting squash and very quickly, the farm went sideways, so Xiao put out a call for extra hands. Without hesitation, Amanda and Walter of Star Route drove two hours to help them harvest. “I think that was really telling of the care and interdependence we tried to build the previous years,” says Xiao. “Community is this word that gets thrown around, but it’s only community if we are creating actual systemic and material interdependencies where we have no choice but to figure it out together, by tying our boat to everyone else’s boat so that no one is left behind.”

Winter days are cold but shorter, which means less daylight to spend in the field. Xiao and Wang are taking more cues from their crops and allowing themselves time to be unproductive, or doing what they love: moonlighting as DJ Dirt, chopping up dinner salads, playing with Music, the farm dog. “We’re building each other through how we take care of each other, us and our vegetables,” Wang promises.

Lately, they have received an uptick in hot meals prepared for them, sometimes by the same mutual aid programs that their vegetables stock. Being fed by their own crops, passed through the hands of strangers and friends back to them, is a salient moment of interdependence.

Their networks of support are relatively new but are rooted in age-old practices of showing care. When friends and lovers visit Gentle Time to help harvest, raid their walk-in fridge and prepare communal dinners, no gesture says “I love you” like someone asking, “Hey, have you eaten?”

Credits:

Written by Leo Kirts

Photography by Ramona Jingru Wang