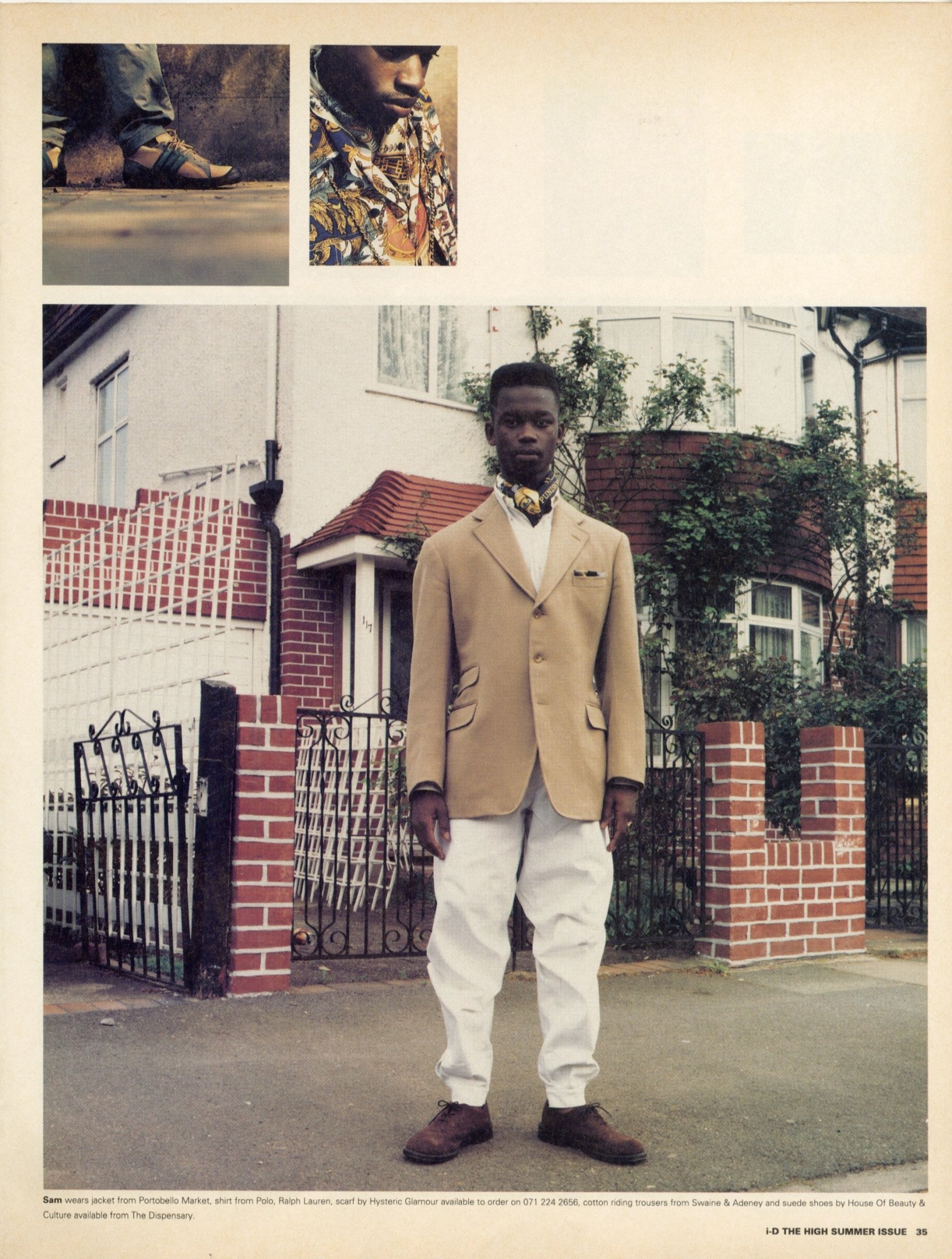

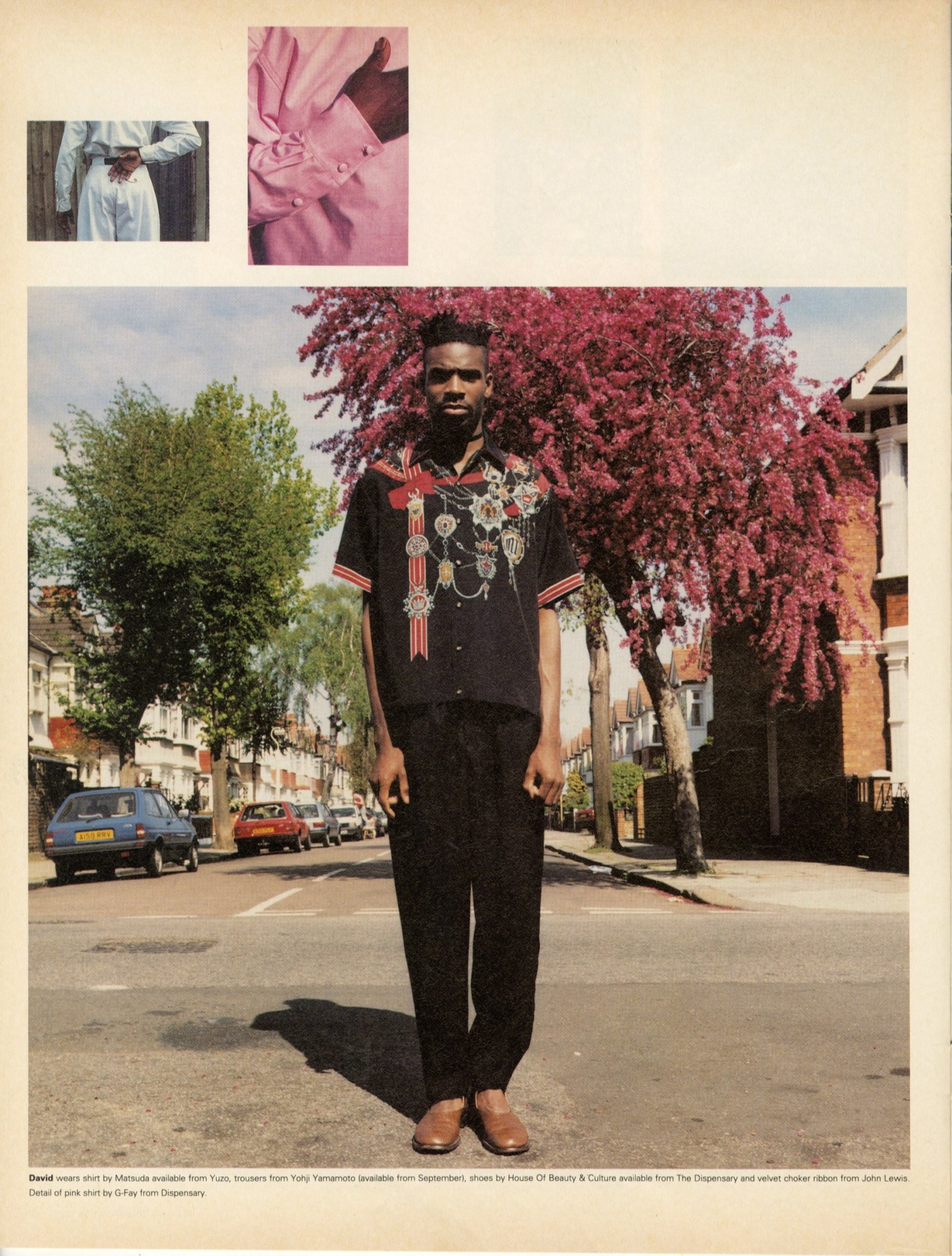

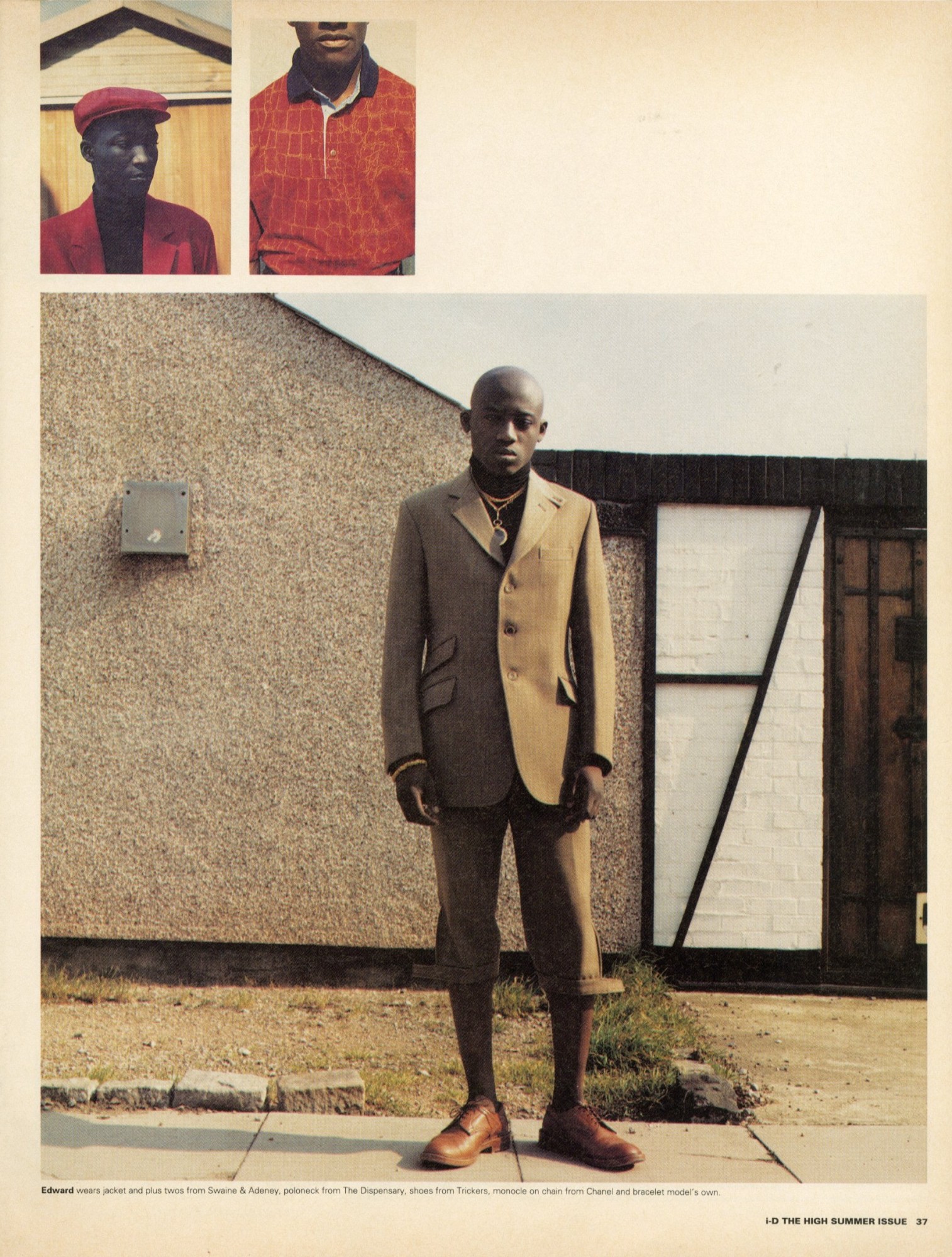

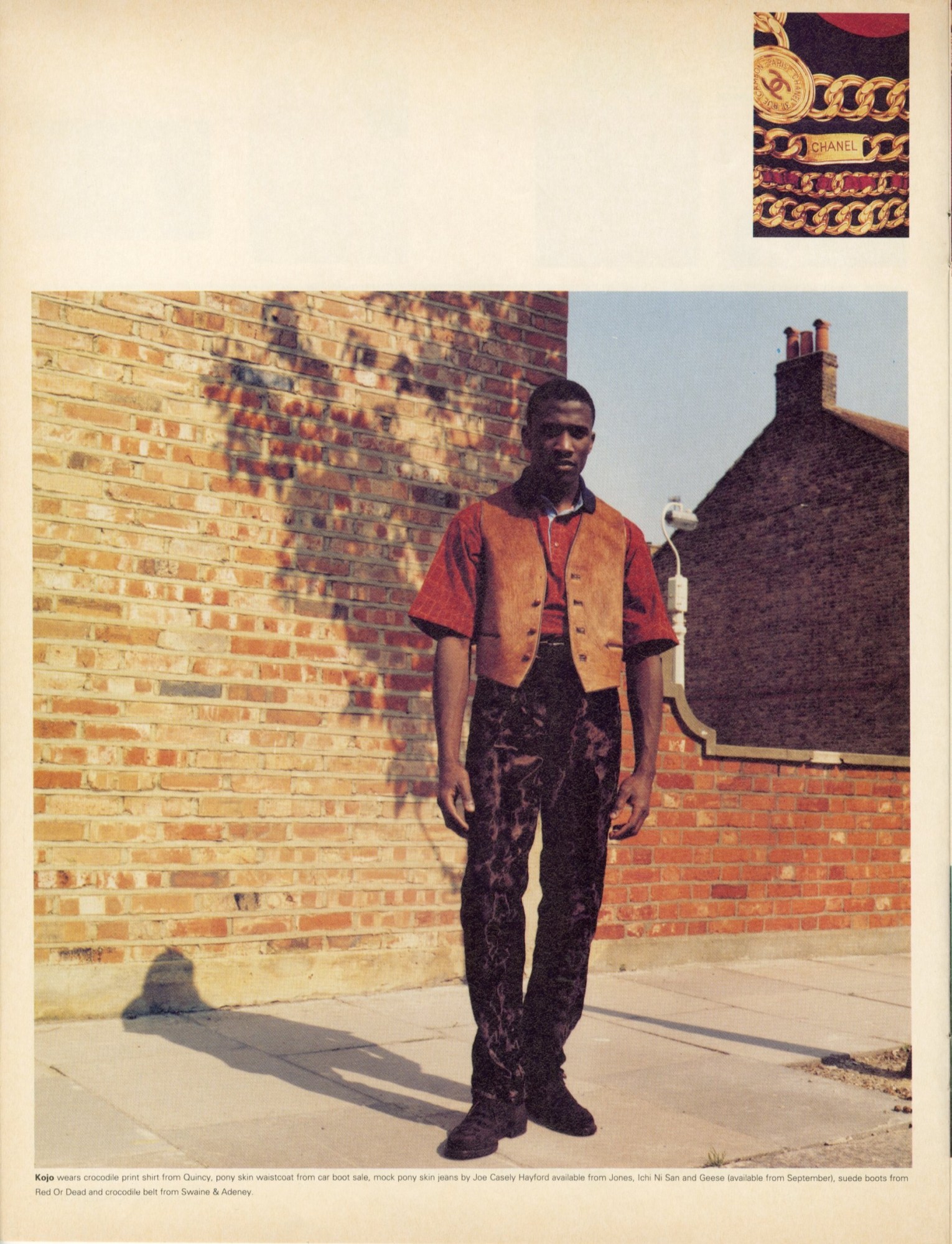

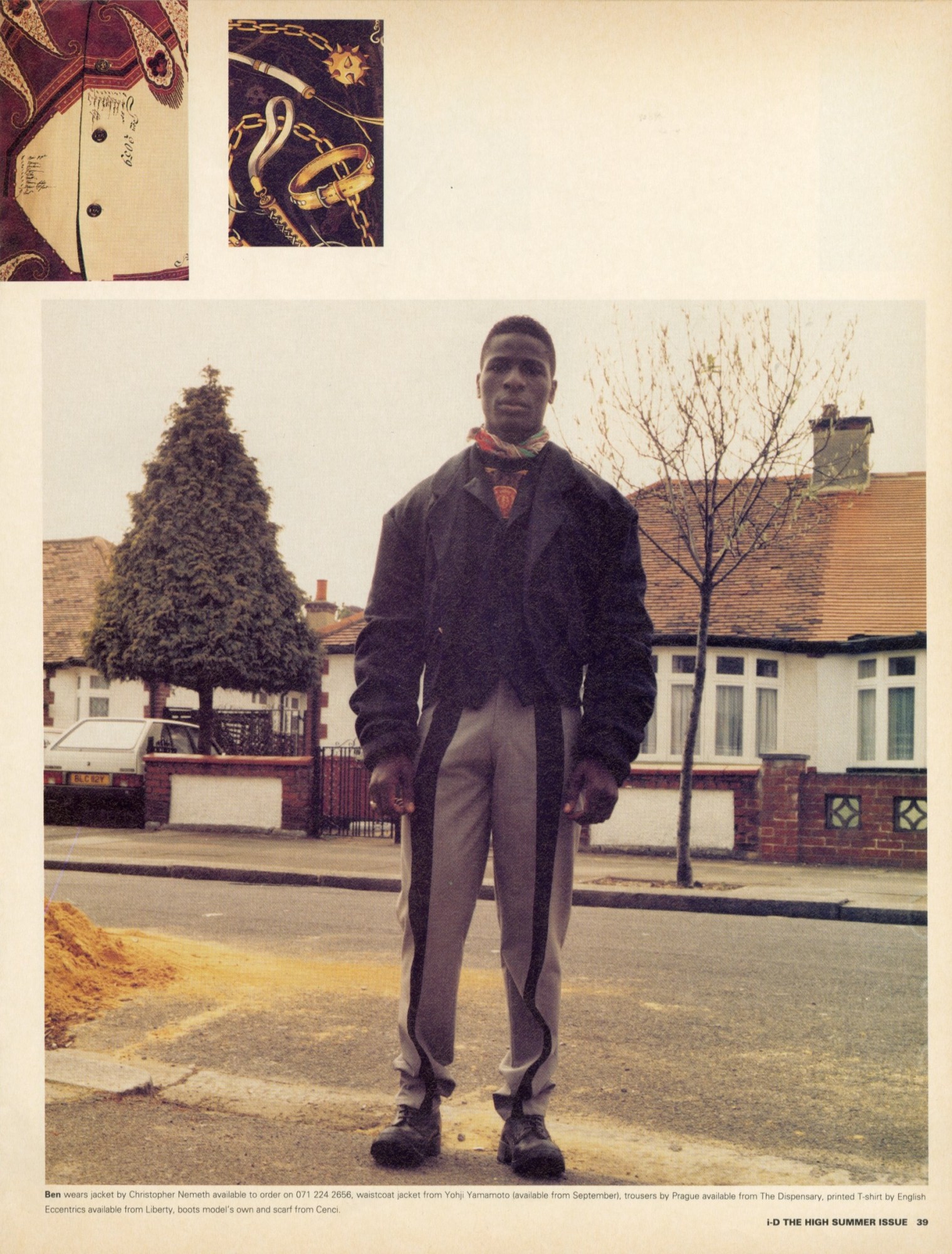

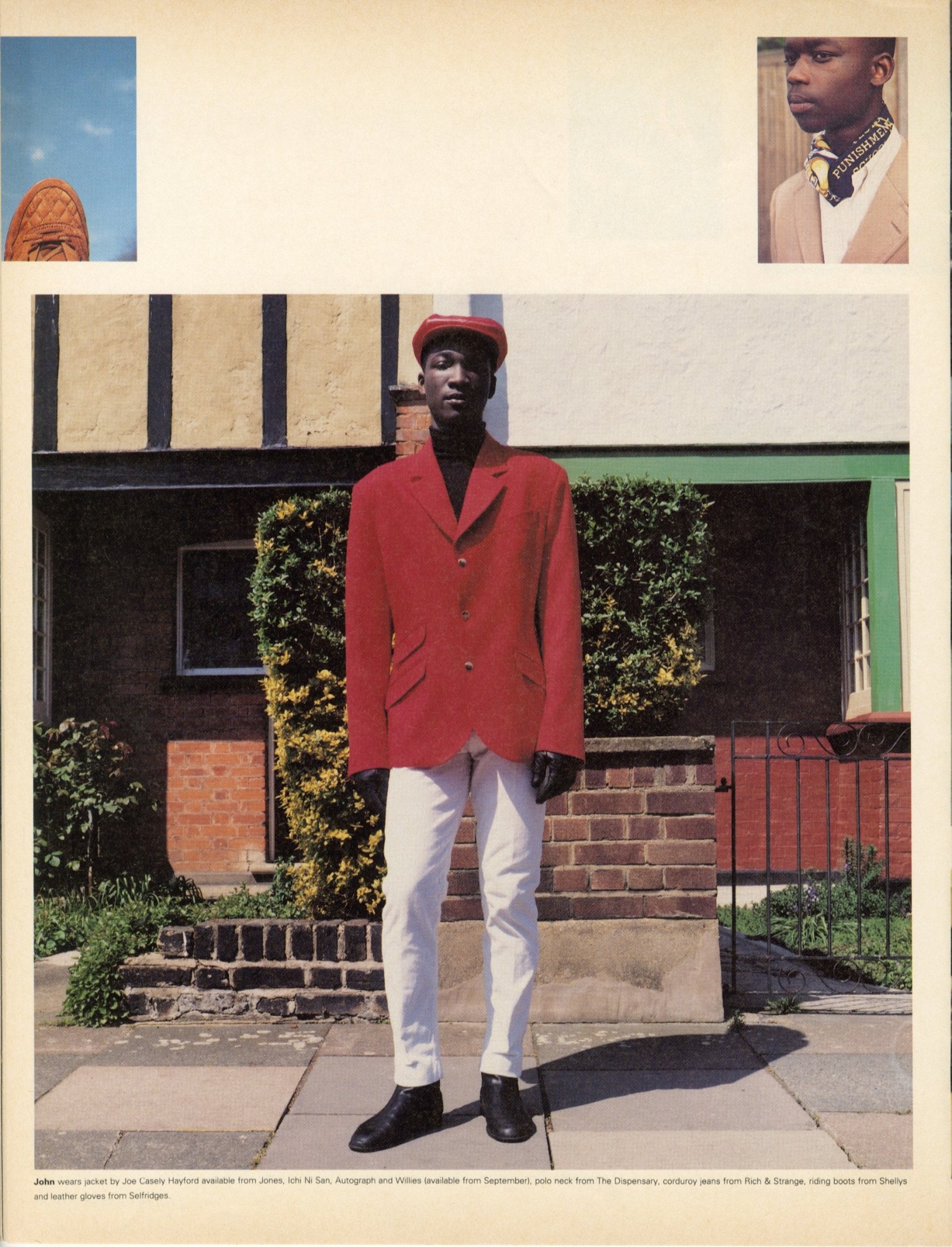

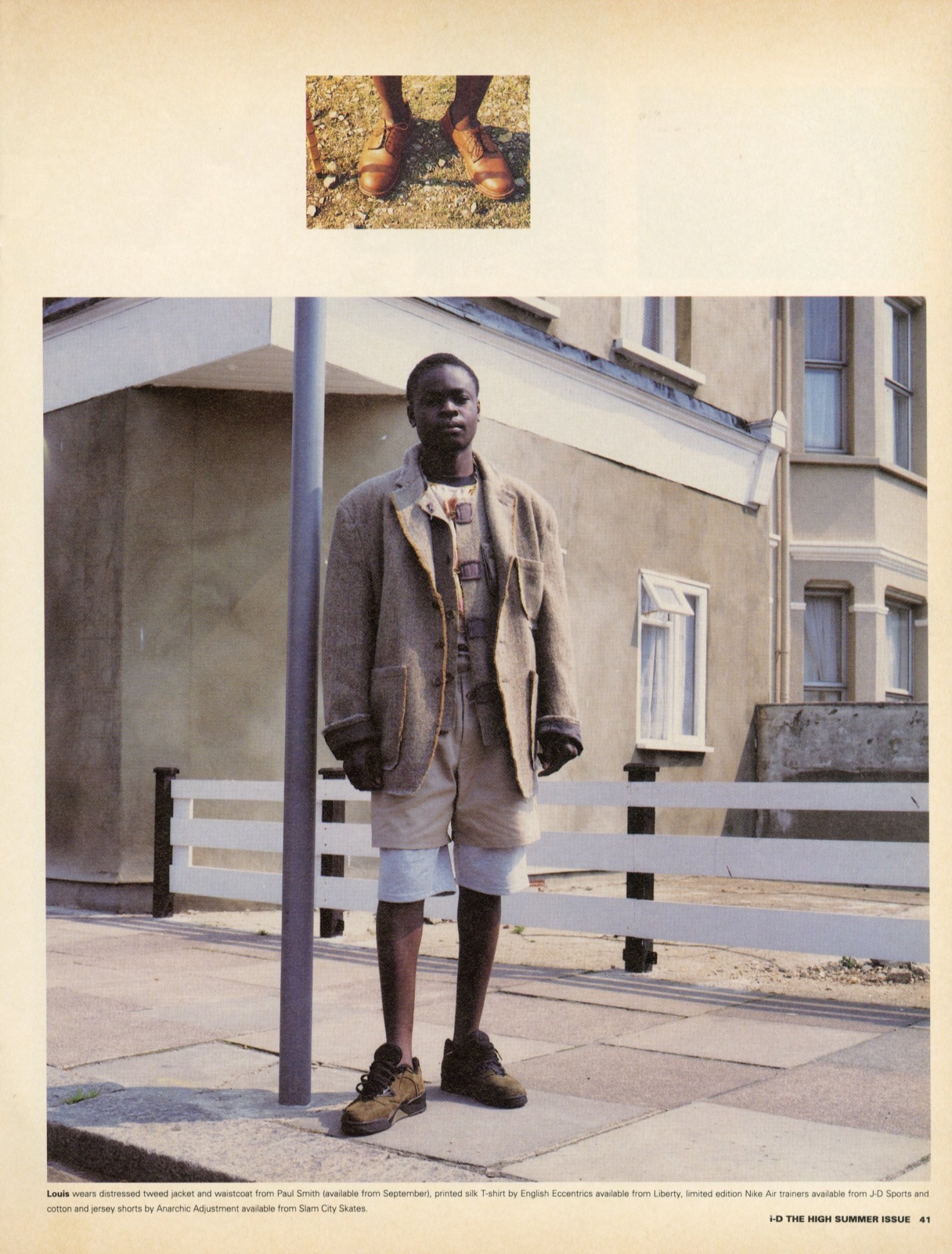

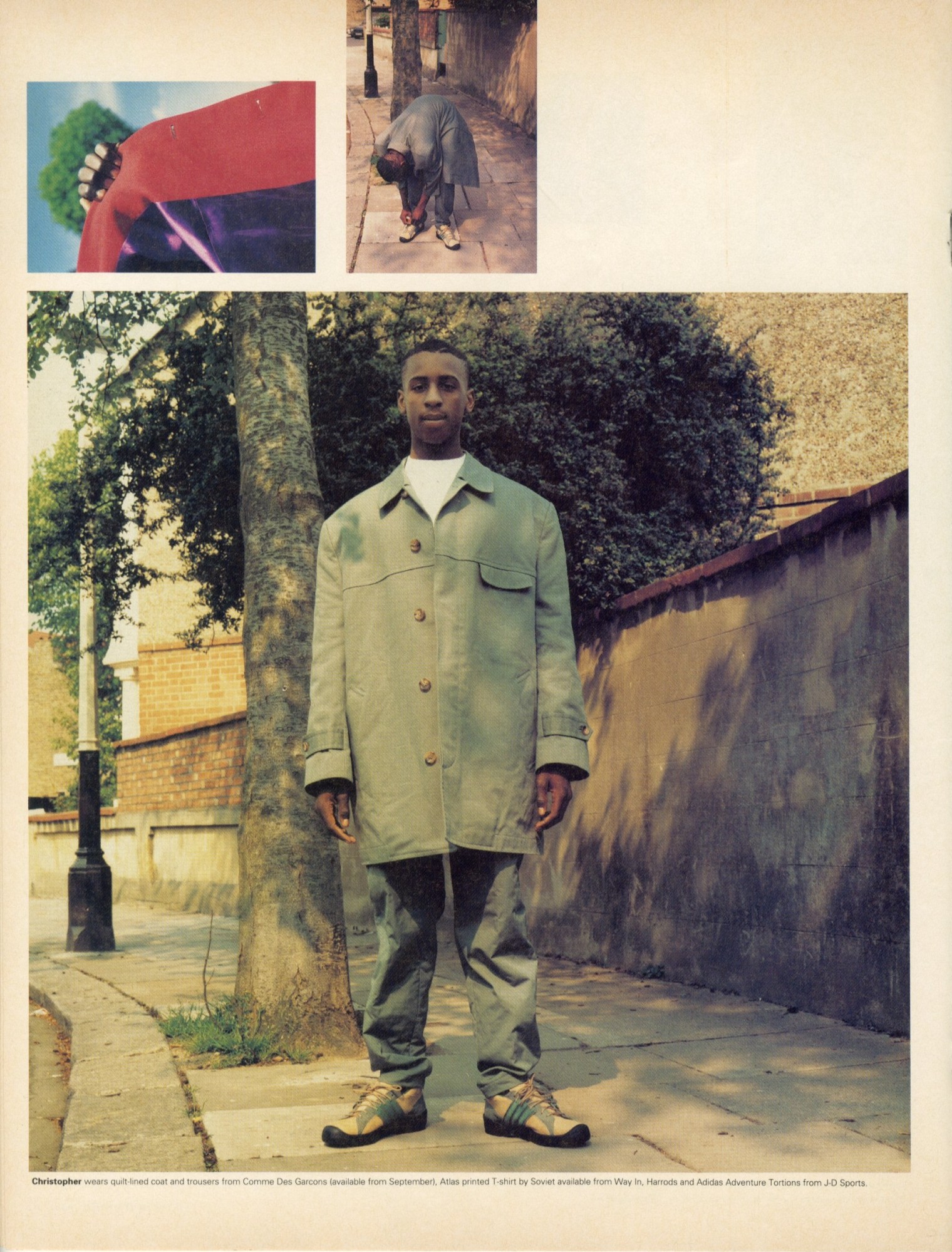

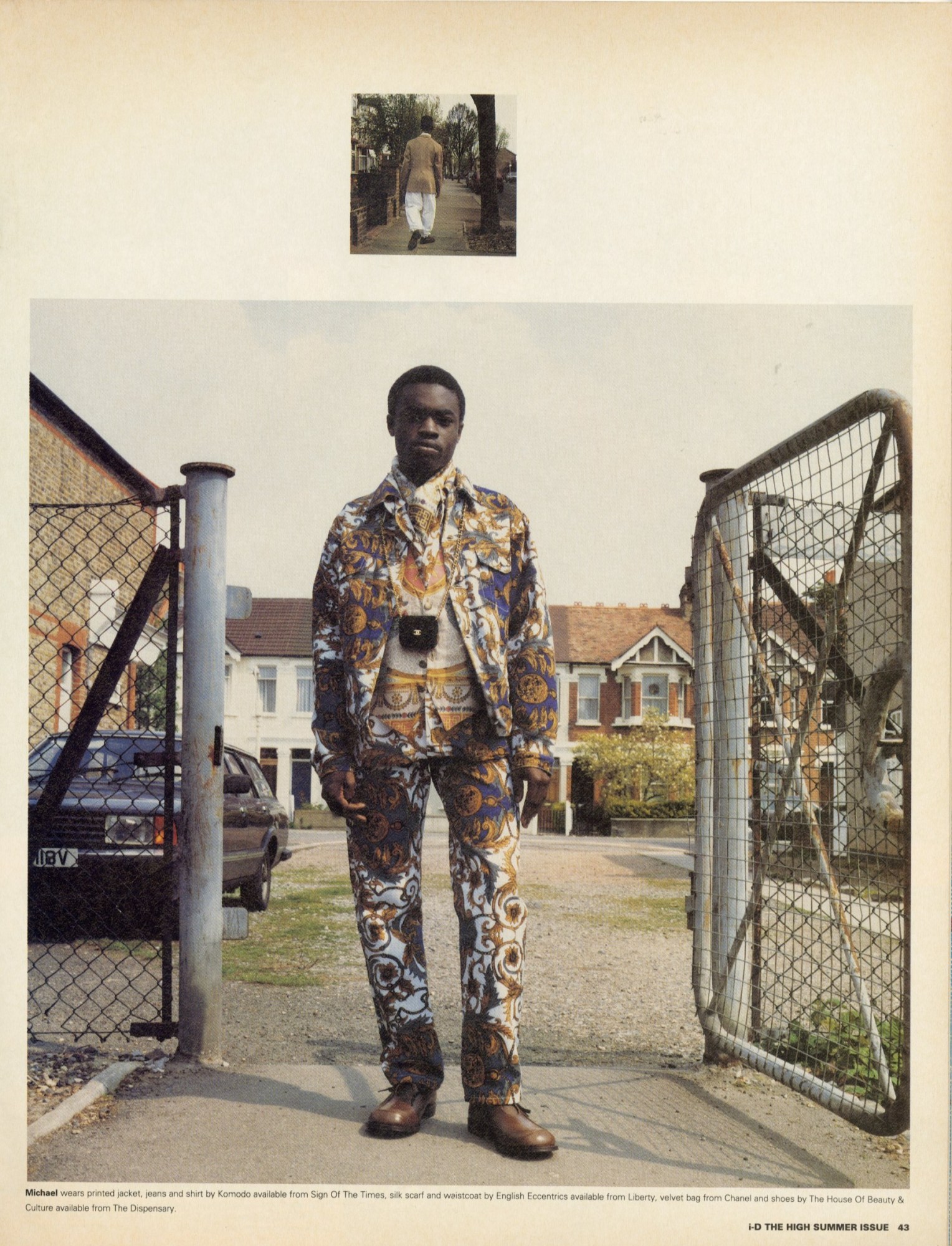

The 80s: Photographing Britain, an exhibition that opened at the Tate Britain in November, features an intriguing series of photographs of well dressed Black men on the streets of residential Ealing. Shot by Jason Evans (who, at the time, worked under the alias Travis), styled by Simon Foxton and cast by Edward Enninful, this now legendary shoot originally appeared in the pages of i-D – The High Summer Issue published in July 1991, to be exact.

Nicknamed “Black Aristocracy” by Enninful, the shoot captured a new approach to Black British style in London at the turn of the decade. To honour this iconic menswear shoot for i-D being celebrated by the Tate, we sat down with Foxton, Evans and Enninful to get the inside scoop.

How did you end up working together?

Simon Foxton: I first met Jason while he was still at college and doing a work placement with Nick Knight. We clicked fairly quickly. He soon started doing his own shoots for i-D and so we decided to do one together.

Jason Evans: I knew Simon’s work before we met, his styling for Nick Knight on a story for Arena called ‘Faith’ was unlike anything I had seen before and spiked my curiosity. This led to a student placement with Nick, and between them they generously included me in their visionary version of editorial fashion. Casting, location hunting, styling, assisting, experimenting, an overview that still informs how I work now.

What memories do you have of the shoot day?

Foxton: We shot over two days using my house in Ealing as a base. It’s all shot in the streets around there, where I still live. It was a fairly relaxed shoot I seem to remember. Edward [Enninful] had done most of the casting, so I think he kept the models happy at my house whilst Jason and I took them out, dressed, one at a time to find a suitable location to photograph them.

Edward Enninful: I have such vivid and happy memories of the shoot we did together. It was a really fun, familial day. The ambition was less about creating fashion pictures, but about wanting to capture a moment in time; the possibilities of being British and the richness of what Blackness represented to us, when Black people weren’t being seen or recognised as part of the fabric.

Evans: It was the first time I’d shot a whole story, or used a tripod for that matter. I followed Simon’s lead, which is unfussy and relaxed. Most of the guys who posed for us hadn’t modelled before, no one was bringing any preconceptions to the process. Beginner’s luck steered by an old hand. It flowed, and the weather was fine for April.

“We wanted to capture the possibilities of being British and the richness of what Blackness represented to us”

Edward Enninful

Why do you think it’s become such an iconic photographic series that now occupies space beyond the pages of the magazine?

Evans: At conception the work was imagined as a riposte to racist stereotypes in our media. I was coming from an 80s art school, culture-jammer position. Our ambition was not to promote clothing but to extend Simon’s cultural proposal. The ambiguous format of the work makes it easier to relocate from page to wall, it’s gallery friendly in a way a lot of fashion images are not. As a white photographer I had access not afforded to Black photographers who were making work at that time.

Enninful: I never set out to create images that would end up in an institution like the Tate, nor did I imagine the impact the story would have on future generations. The idea was to just capture something pure and of the moment, and I’m so proud that the story became an historical documentation of our times. In truth it’s shoots like this that continue to fuel and drive me.

Foxton: I think its simplicity and repetition is very appealing on one level. Also seeing young Black men in slightly dandyish clothing in very suburban settings was novel back then. I think it just struck a chord. Here was a series of men of colour holding your gaze unapologetically, as if to say “we belong.”

What was your reaction when the Tate asked to use this series as an example of important British photography from the early 1990s?

Foxton: Obviously extremely delighted. It’s always nice to be recognised.

Enninful: I was exhilarated. For the significance of a small story shot with my Ladbroke Grove friends and family as cast members to be recognised by such a big institution showed me the power these ambitions can have.

Evans: Honestly, slightly confused, as the show is about 80s photography, which definitely informed my approach but… The show is huge, I haven’t digested it yet. It starts in the late 70s and ends in the early 90s. It’s always nice to be asked though, right? The Tate has shown the work four times now, I think they were the first fashion photographs to be included in their collection.

What was the inspiration behind the shoot? What were you thinking about when creating it?

Evans: I had been reading Baudelaire, about flâneurs and dandies, and found this quote from Beau Brummell which we used as an intro: “No perfumes… but very fine linen, plenty of it and country washing. If John Bull turns round to look after you, you are not well dressed, but either too stiff, too tight or too fashionable.” This exemplified a sense of “the dress code” – the conservatism, discretion and reservation that I liked about certain types of British menswear.

How did Edward end up modelling in the shoot?

Foxton: Edward was my assistant at the time and so he had helped enormously with the casting. We didn’t want proper models so he enlisted a lot of his friends and family. He’d modelled for me before so it was an obvious decision to have him in this shoot too.

When you look back at the shoot now, how do you feel?

Foxton: I still think it looks good. I feel it has stood the test of time pretty well. Some of the styling I might change a bit but overall I’m proud of it.

Evans: It’s amazing that the work resonates for people all this time later. It has a life of its own now.

Credits

Text: Eilidh Duffy