When photographer Keiran Perry answers his phone, he’s in his van en route to Glastonbury for a shamanic gathering. Much has changed since his life, pre-COVID pandemic, in London. Back then, he spent much of his life working in advertising – an artist in a stifling, through lucrative, system – with a want to do something bigger. “When I first moved to London, I just used to wander around with my camera, and meet people in the street,” Perry says. “I could lose three hours with some strangers, and somewhere within that conversation, perhaps a photograph would emerge. It felt like such a symbiotic thing.”

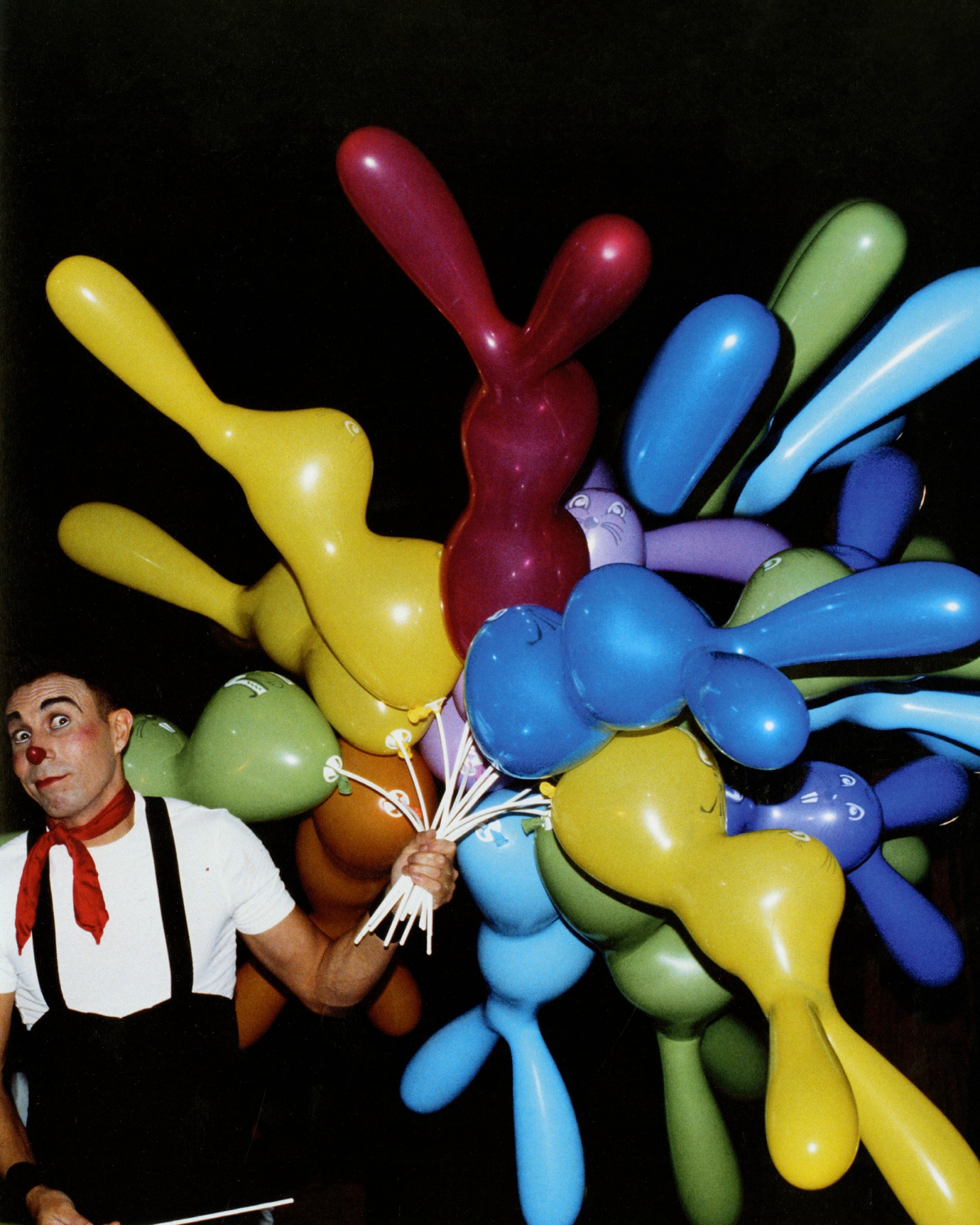

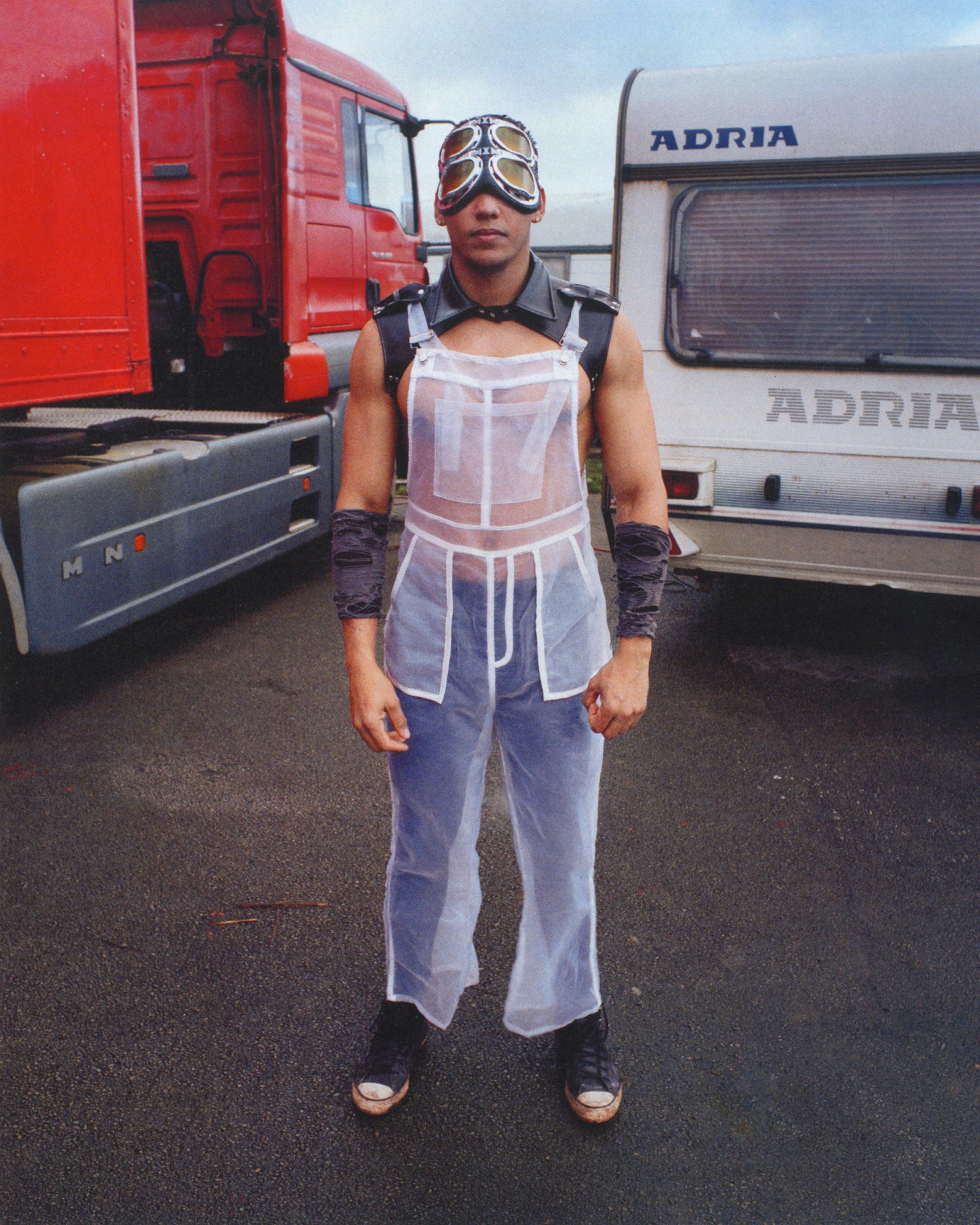

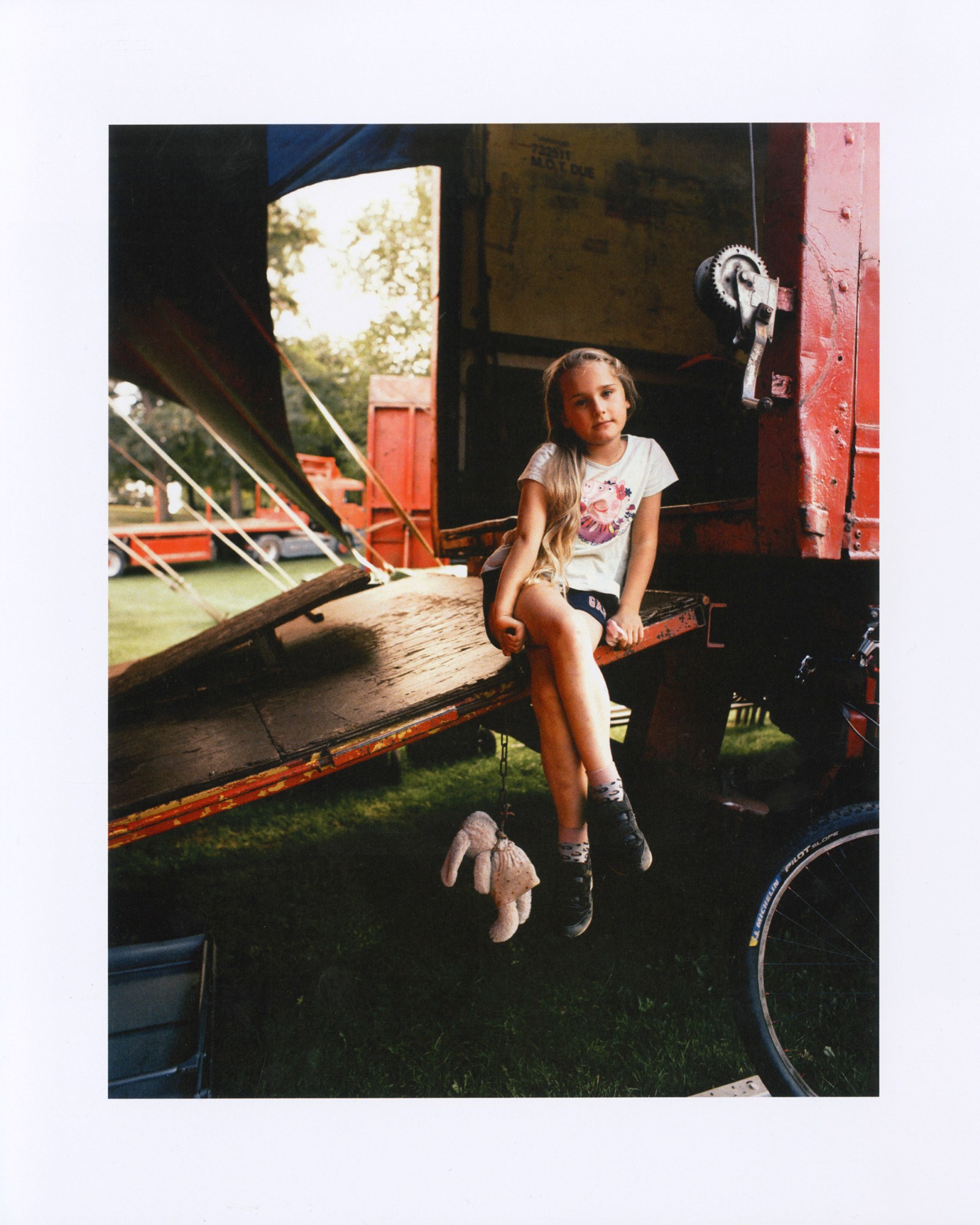

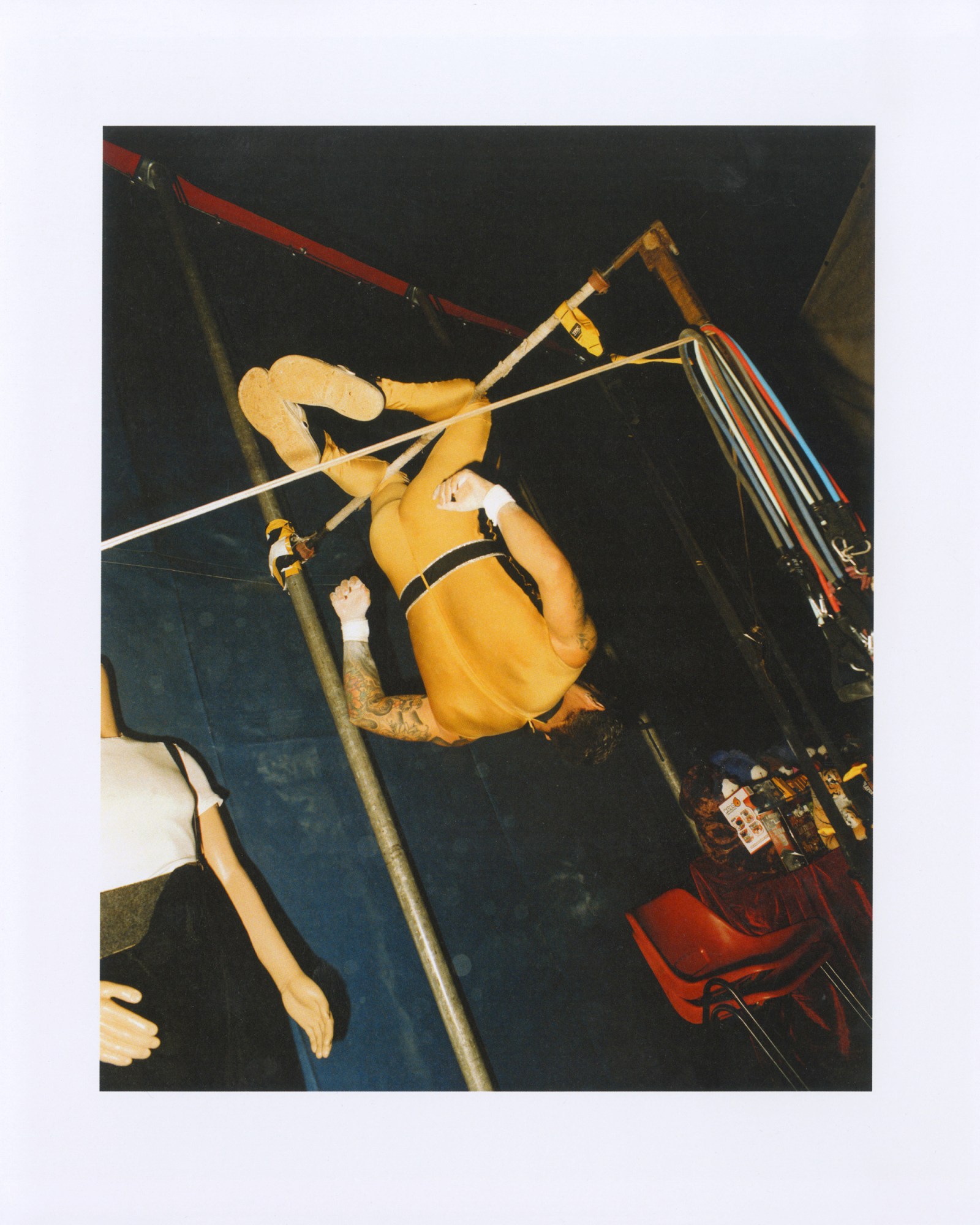

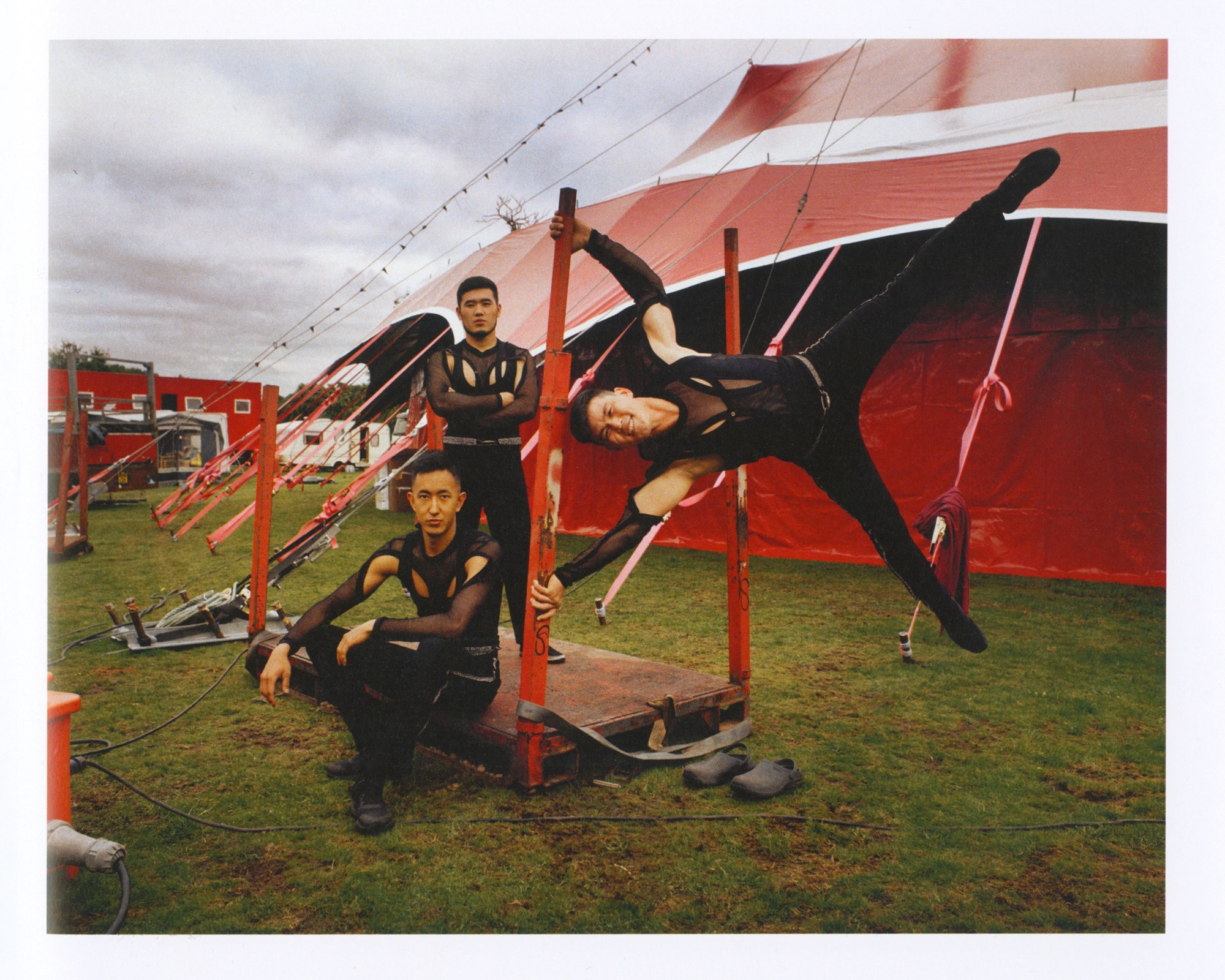

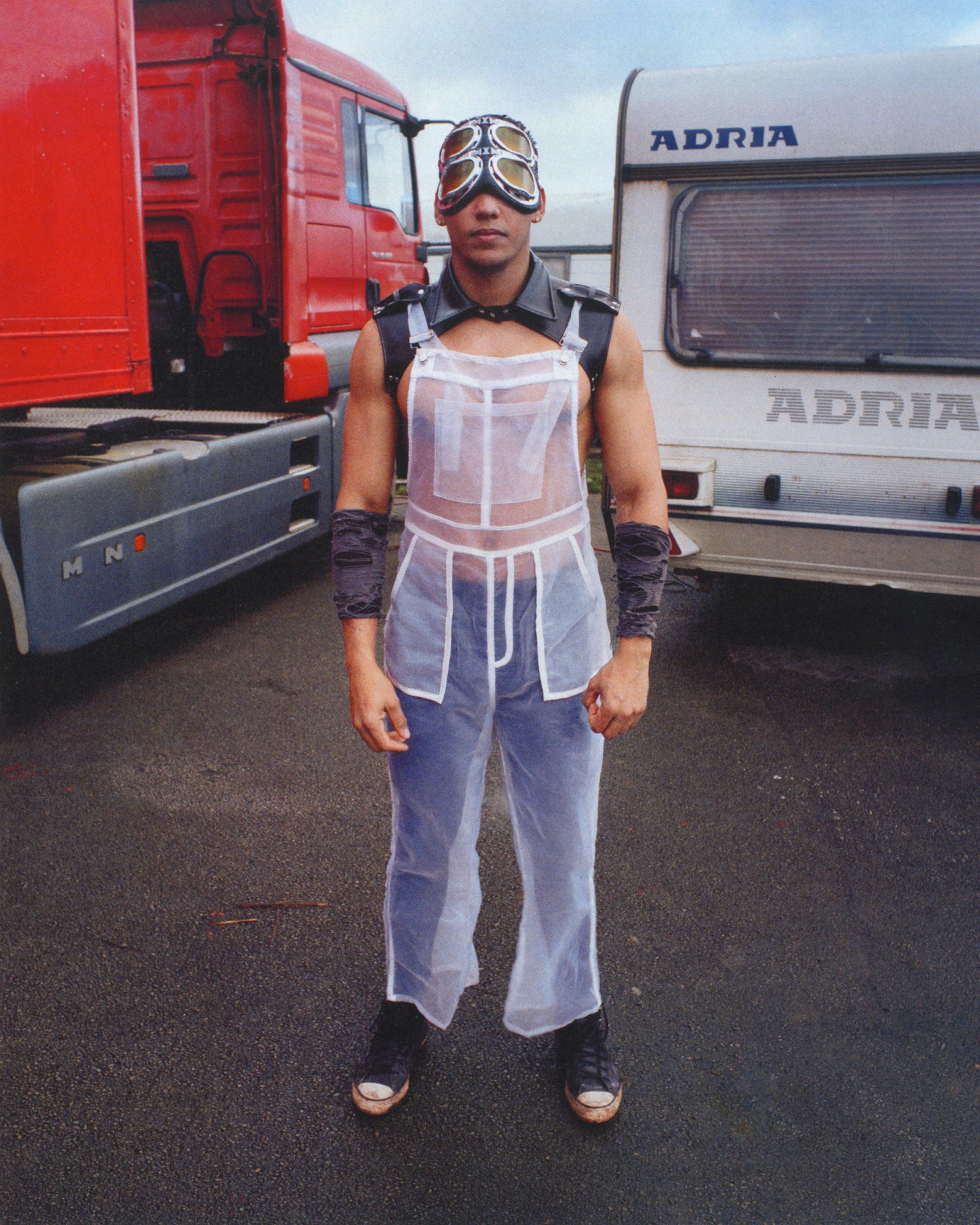

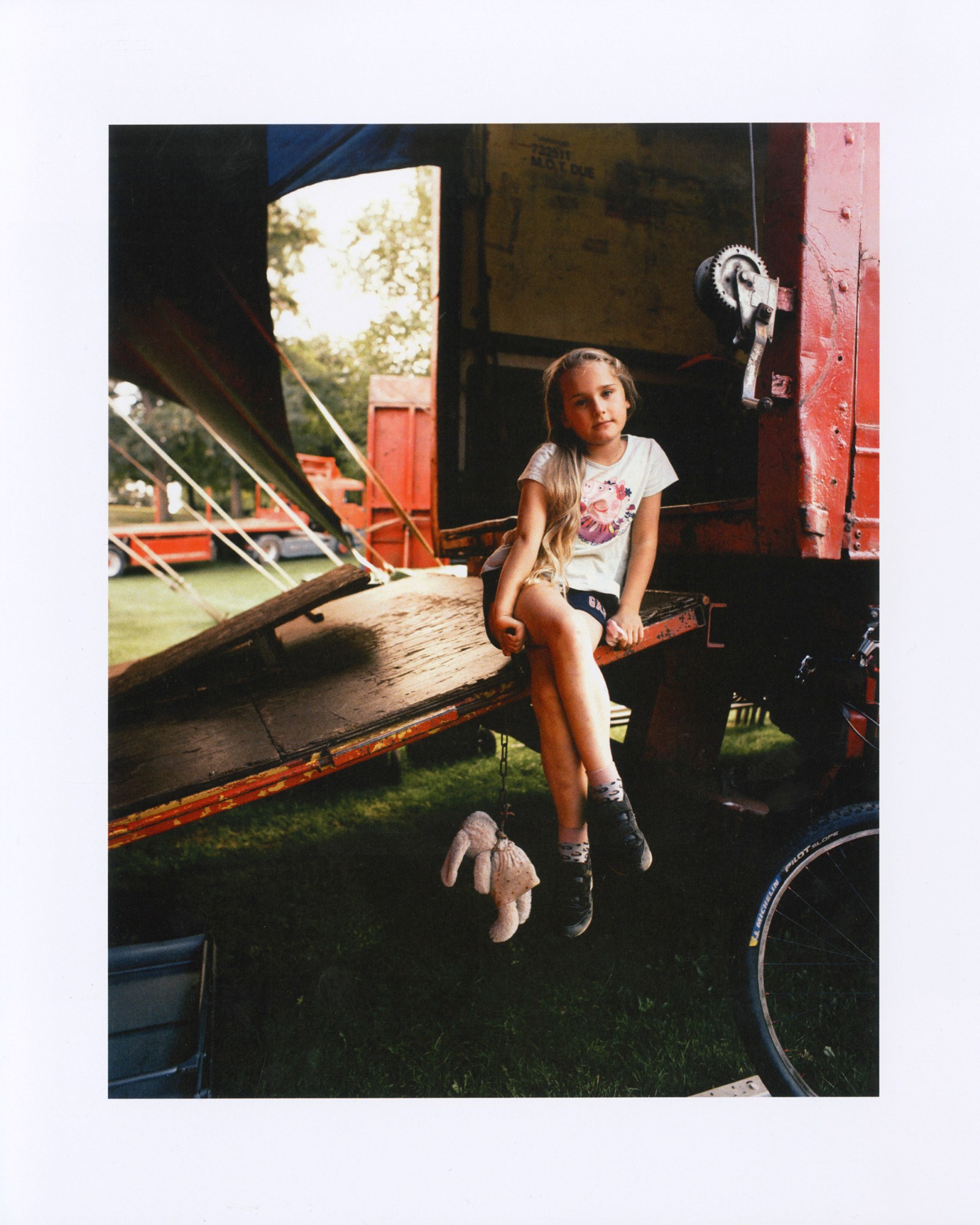

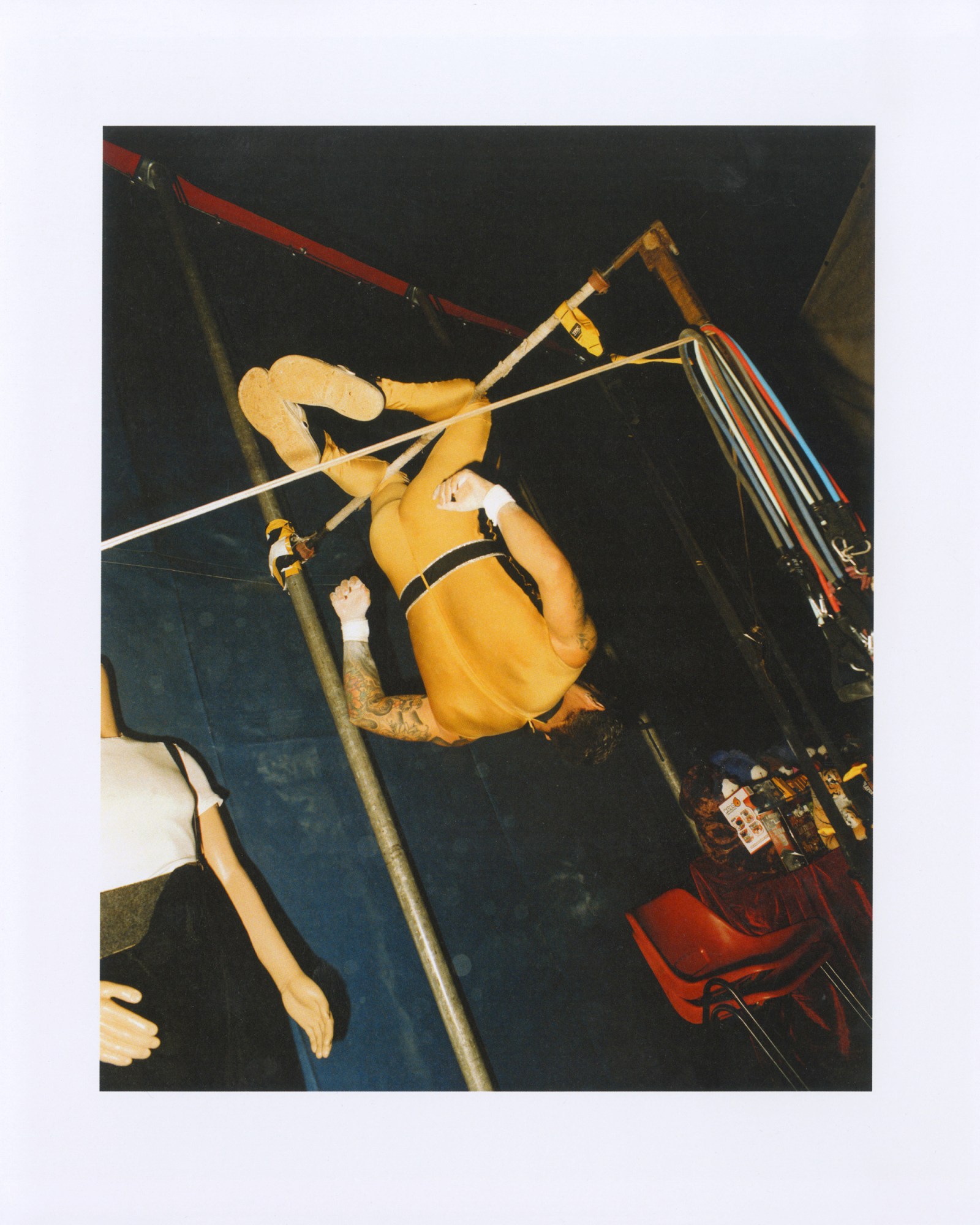

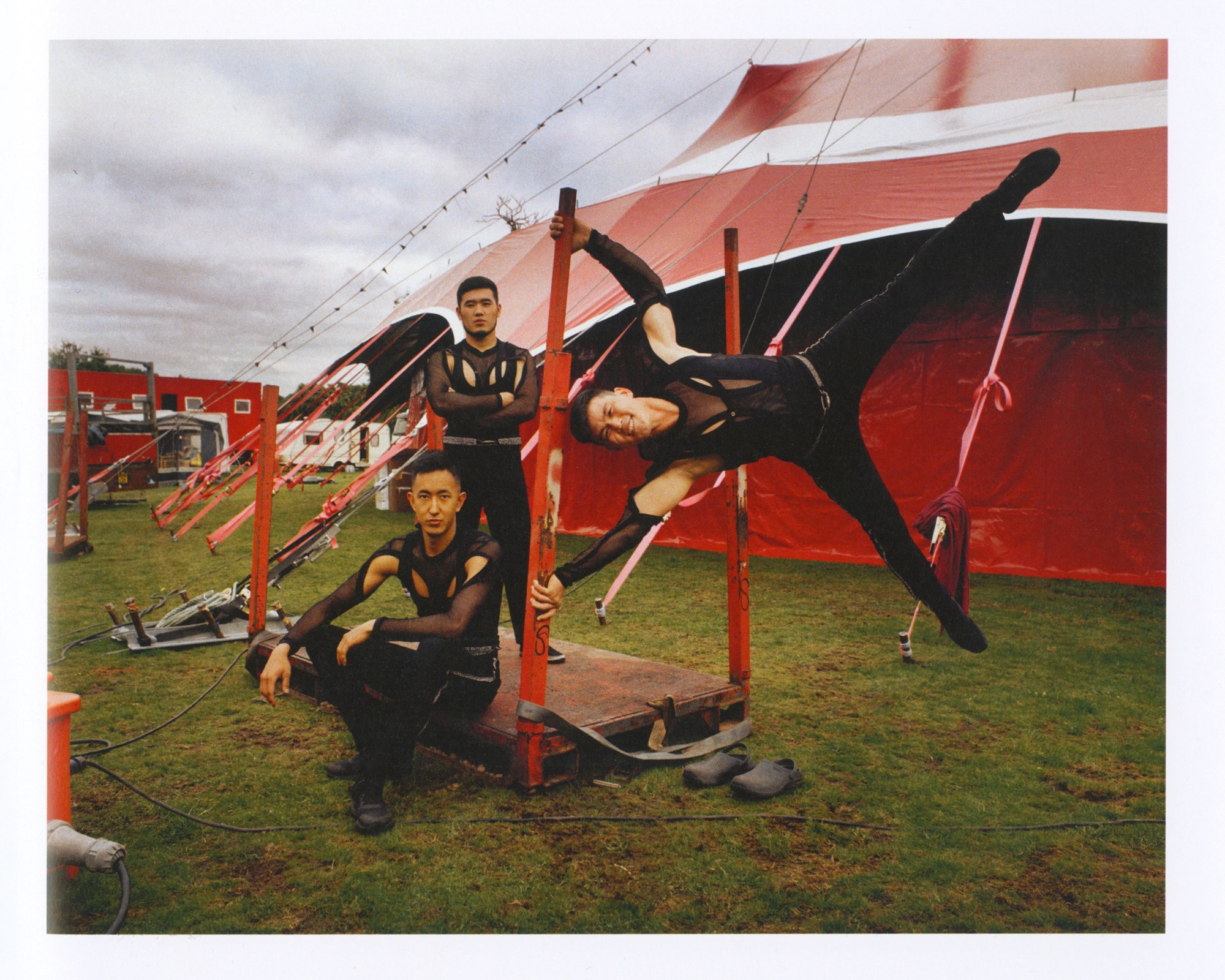

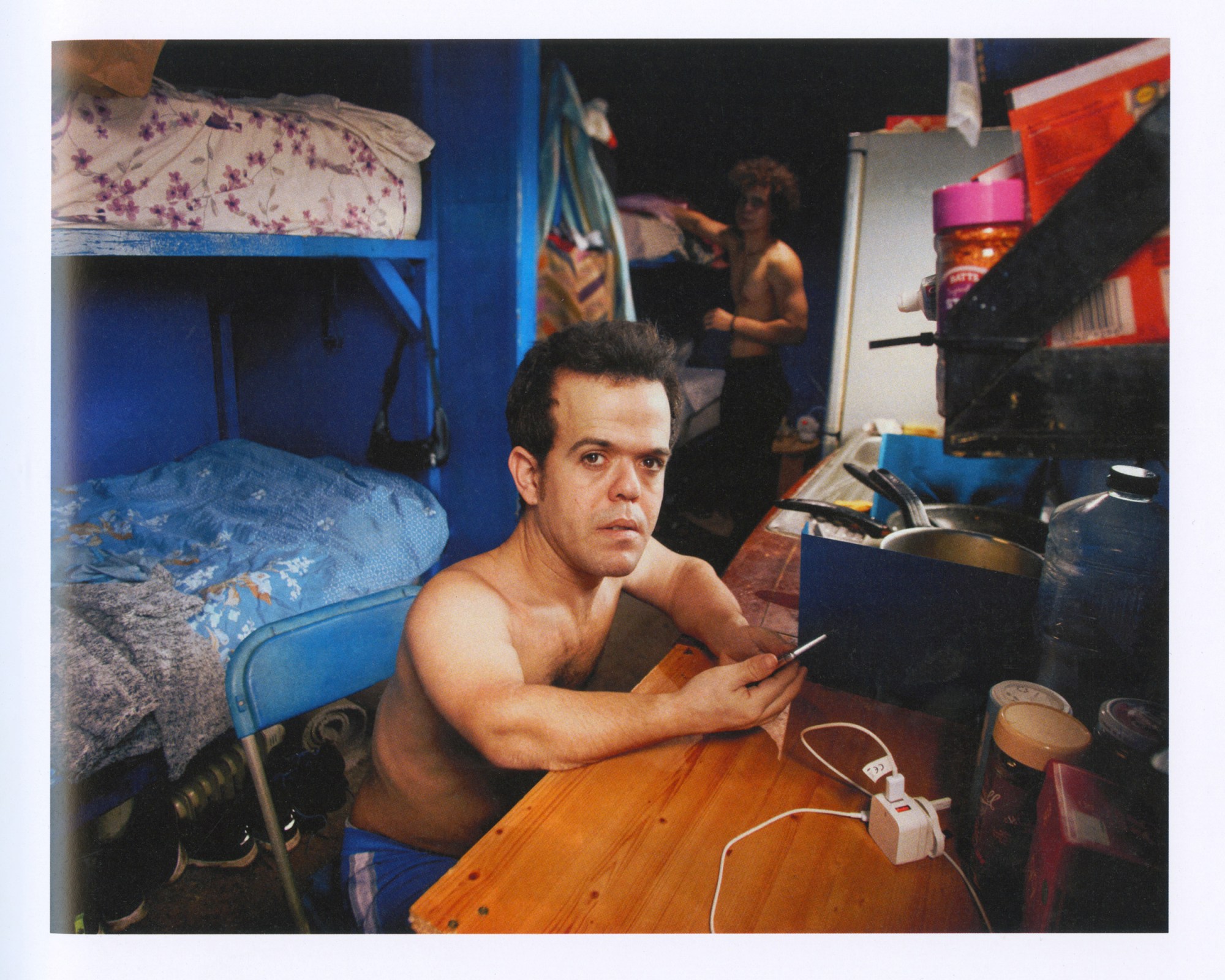

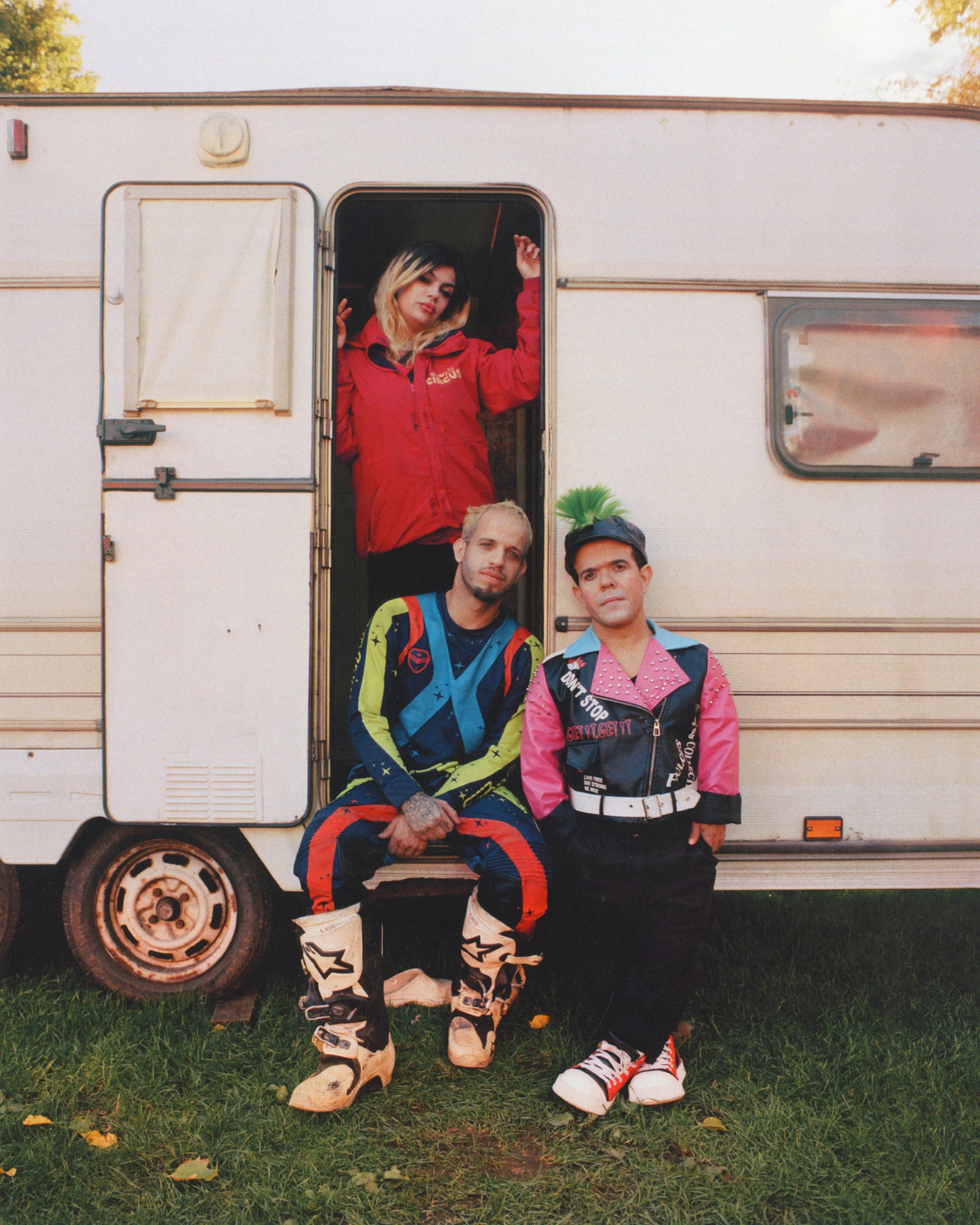

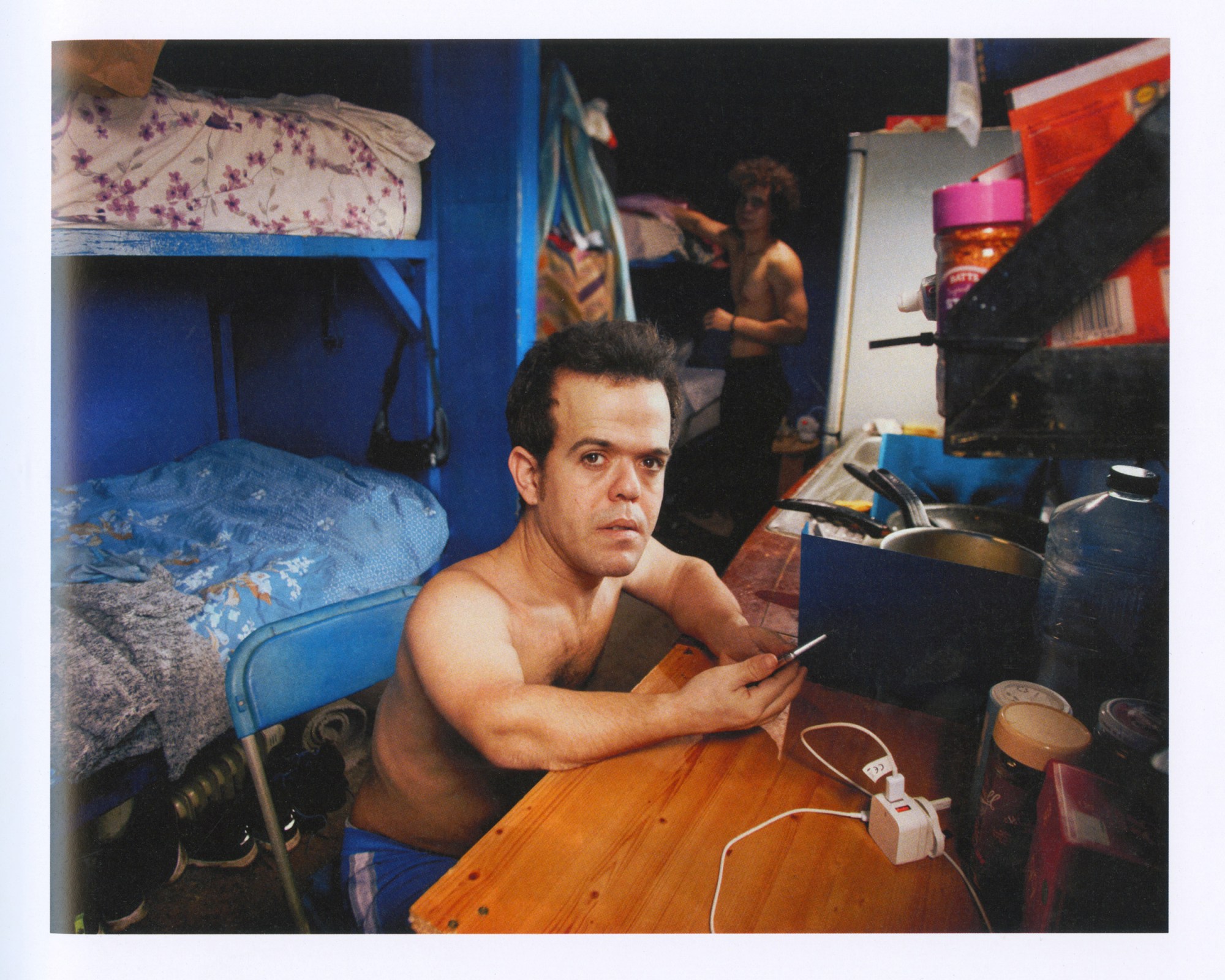

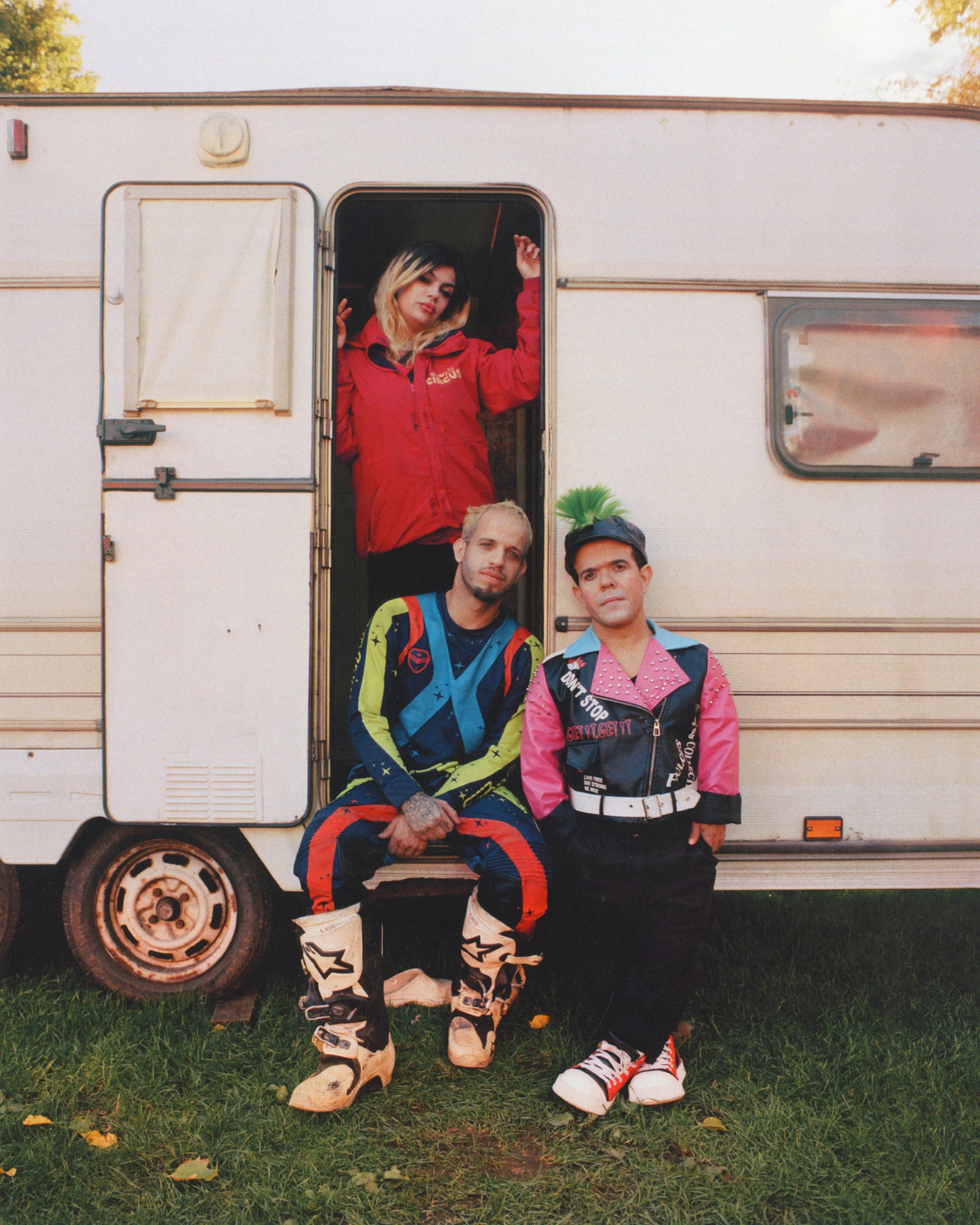

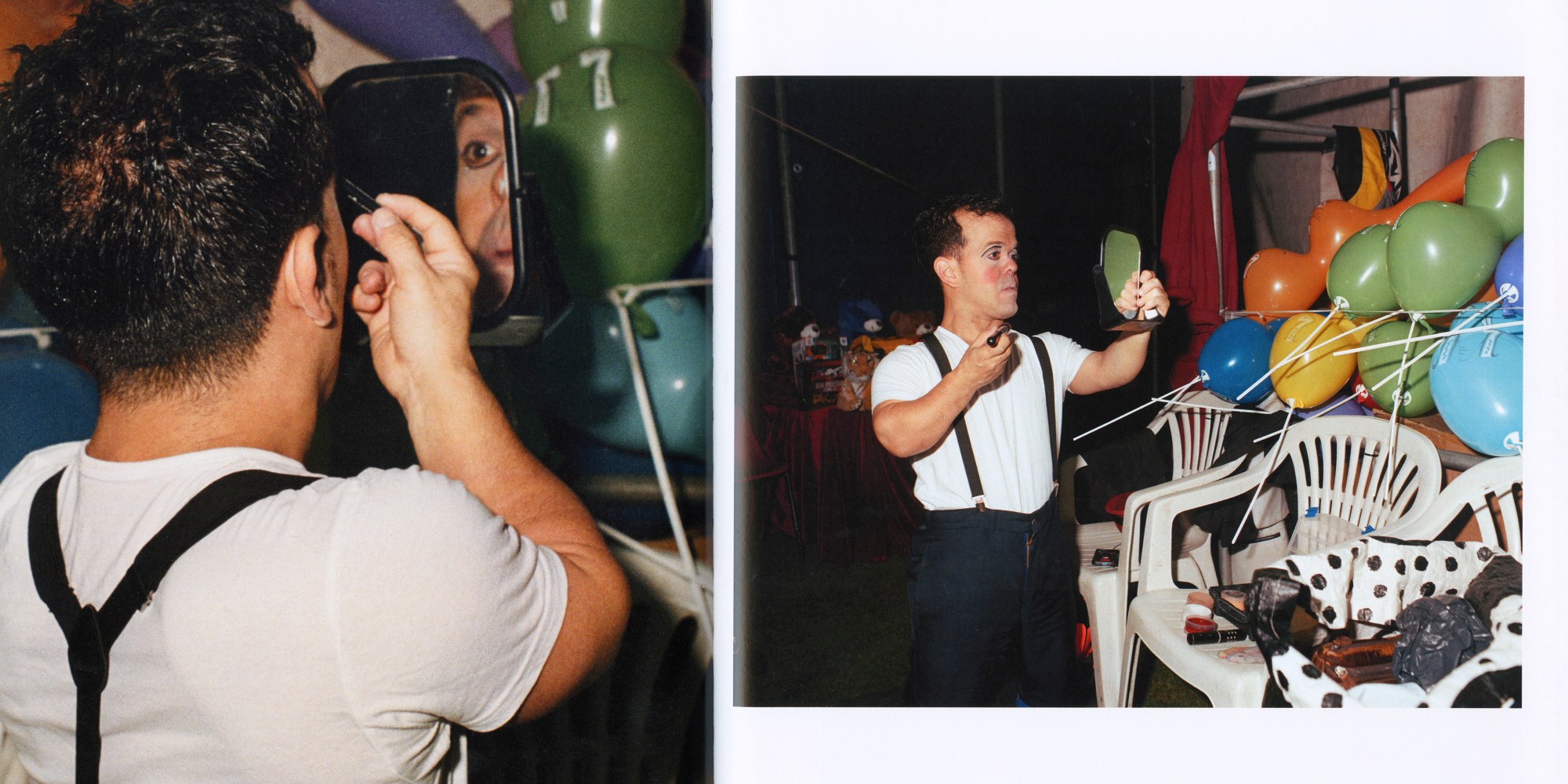

Like most people, the pandemic forced him to look elsewhere, and think of what else he could do with his life. That led to the creation of the body of work present in Smoke Filled Mirror, his new monograph comprised of the images he took over two years spent with a travelling circus, who he met in the English town of Morecambe and rarely left. While with them, Perry ventured to the Highlands, and encountered an off-grid community, who he befriended – hence his current interest in shamanism. (That community is the subject of another monograph, Whispers on the Wind, currently in the works.)

Here, Perry tells us everything about his time with the circus, from that fateful first encounter, memorable people he met, and why hitting the road with the group reminded him of home.

What’s your name? Keiran Perry.

Where do you live and where are you from originally? I’m from an old weaving town called Burnley in Lancashire, but live in North London now.

How do you describe what you do? I’m a photographer, but I see myself sometimes as an anthropologist.

Where did the idea for the project originate from?

During COVID, I built this big shed in my back garden and moved all my things into it. Then I rented my house out and buggered off in my van. My friend Lizzie is a filmmaker, and she’d come across this traveling circus that had been stranded in Morecambe. So I headed to Morecambe Promenade and arrived at night. It was pitch black and pissing it down with rain, sideways pelting in from the sea. All I could see was a big top tent and these caravans in the darkness. A big dog stepped out of the shadows of this tent, and it picked up a hot dog on the ground, covered in mustard and ketchup, and swallowed it whole. A voice cried out from one of the caravans, and it belonged to Julia, the daughter of the circus owners. She invited me in, and we had a cup of tea. The next day she said she would introduce me to everybody. I asked if I could maybe hang out for a couple of days and take some pictures. I thought I’d maybe stay for a couple of days, but I stayed, that first time, for two weeks.

Did you have any revelations during the creation of it and, if so, what were they?

The mind thinks and the heart knows. Something really difficult might be happening, but rather than seeing it as an issue, I started to see it as a gift.

Can you recall a memorable figure you met while making it?

One person who really stuck in my heart was Valeria. She’s a dancer and choreographer from Ukraine, and her mother and grandmother fled the country to join her in the circus after the war. Valeria has a baby now with the son of the circus owners. There was a moment when Valeria’s mum picked up Valeria’s daughter and gave her a kiss. I had my camera with me, and caught the shot.

What about the project moved you?

When I first came across this circus, they were quite DIY. It reminded me of my time growing up, in a way. I grew up in a bit of a makeshift community. My mom was sort of an anarchist, with an anarchy tattoo on the back of her neck and a shaved head. She was a young mom and pretty lively. A lot of those different characters from all walks of life used to kind of just come round to our house. And when something broke, everybody just banded together and fixed things. The circus reminded me of that: everything was in this constant state of disrepair, but it didn’t matter, because everybody was there to fix it.

What’s the defining image or work of your lifetime, made by someone else?

“Gordon in the Water on Sea Coal Beach” by Chris Killip. I love how elemental it feels. It’s a bit of a symphony of the powers of nature. But in all honesty, I rarely look too deeply into photographs. I find myself more drawn to painters, in particular Lucian Freud. His portraits don’t flatter, they show people as they are.

What is your favourite ƒ stop?

On my Pentax 67, medium format, the lenses are a little more shallow, so I’d be at ƒ11. For 35mm, I’d hover around ƒ5 or 6.

Who is your dream subject?

Roger Penrose.

What are two things you love and one thing you’d change about your job?

Firstly, I love adventure. My mum’s adopted, but her blood relatives were Welsh gypsy travelers. I think it’s just in my bones.

But I sometimes see photography as a bit of a curse and a gift, so I can answer both with this. On the one hand, it’s this incredible vehicle to go and interact with the world and talk to a stranger. It opens a portal to things. But on the flip side, sometimes you view the world through a lens, even when you don’t have a camera. I think that’s why the experience is so important to me. Often when I was with the circus, I wouldn’t take pictures for days. I just wanted to be part of it.

Smoke Filled Mirror by Keiran Perry is available to buy now via New Dimension

Credits

Words: Douglas Greenwood

Photography: Keiran Perry, courtesy of New Dimension

For New Dimension

Art Direction and Design: Alex Currie

Editor: Sherif Dhaimish

Creative Direction: Ben Goulder