In 2001 at the Cannes Film Festival, David Lynch unveiled a film that would, in the decades that followed it, become synonymous with thematically labyrinthine storytelling. Mulholland Drive, widely seen as a neo-noir mystery thriller, was in the eyes of its creator, a love story. Its plot changes depending on who you talk to; its protagonist and mood shifting constantly, even today, nearly 25 years after it first premiered.

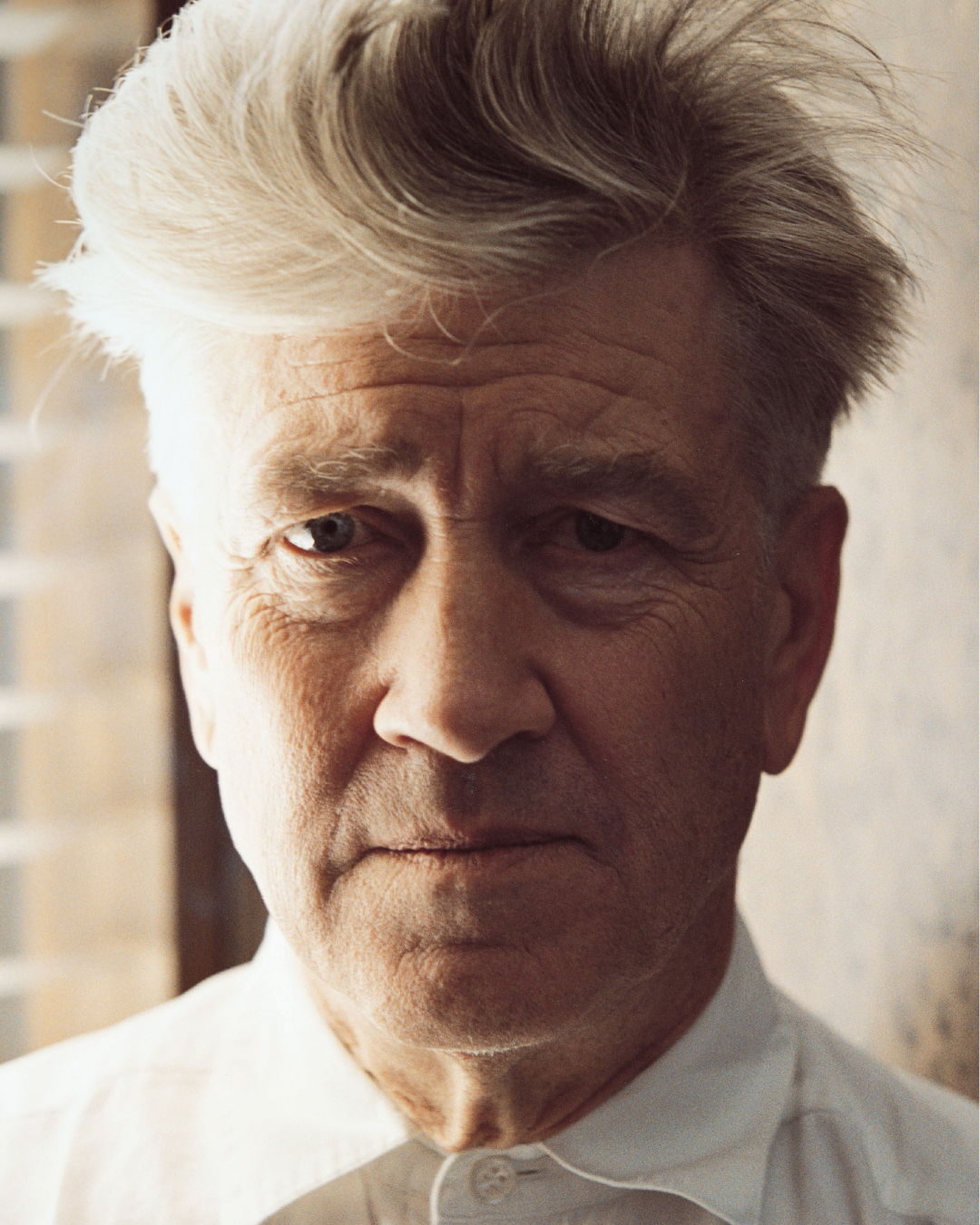

In the aftermath of its premiere, just as it was preparing to be released in the UK, journalist John Dunning spoke to David Lynch for the February 2002 issue of i-D. In the wake of his death, their conversation reads like a time capsule of how the then-56-year-old director saw himself and his work. In the conversation, published online for the first time, Lynch unveils the roots of Mulholland Drive, the films of his that make him cry, and where he fits in the blockbuster-arthouse universe.

Your new film, Mulholland Drive, is rather impenetrable, a mystery with no clear resolution. What inspired it?

Mulholland Drive, like anything, is based on a set of ideas. I always try to tune into those first ideas and let them talk to me, and follow them wherever they lead. From that I develop a story populated by characters. I guess the initial spark for the film was the name, Mulholland Drive; the signpost in the night, partially illuminated for a couple of moments by the headlights of a car. It was that simple.

Does the place actually exist?

Yeah, it’s a road in Los Angeles that goes along the crest of the Santa Monica mountains. It’s a beautiful road that gives onto vistas over the valley on one side, and Hollywood on the other. It’s a mysterious road – really dark at night and, unlike so many other spots in LA, it has remained the same through the years. I find myself inexplicably drawn to it.

Mulholland Drive was originally made for TV: how did that impact the style?

It was originally a pilot, so by necessity it needed to be open-ended. You set many things in motion, but you don’t have to close the door. I did this pilot and at the same time I was working on The Straight Story. It was rushed and I wasn’t happy with what we did in terms of finishing the pilot for ABC (TV Network). They hated it. That opened the door for other possibilities: in my experience, if a story wants to be a certain way, then that’s what it will be. So it wasn’t a total letdown. In fact, there was a little air of euphoria at its rejection for TV, and I pay attention when I get a little air of euphoria. The main male lead, Adam, is a film director, forced to change his work due to business expediency.

Have you shared his experience of that?

I think most directors have. I always worry about someone forcing me to do things because as a director I identify so much with my work. If certain demands go against what I believe to be correct, it’s a horror. Being somewhat paranoiac, I worry about these things. If you don’t have final cut you can lose your way very quickly and die the slow, agonising death.

Adam’s story shows the more manipulative elements inherent in directing – were you drawing attention to the same in your own work?

I don’t believe in manipulating anyone. I try to remain true to the original ideas for a project, and if I fall in love with them, I can only hope that others will as well. Sometimes I’m wrong, but the main thing is that film is not about manipulation for me. It’s about being true to the original ideas and then acting and reacting as I try to make them coherent.

Is the character based on yourself?

No! No movie can tell everything about anything. This particular story touches on some small part of film making. Sure, Adam is a film director, but there’s another film director in there too – it’s just a small part of a particular story I’m telling. Some people have seen satirical elements in the film, particularly with regards to its skewered take on Hollywood. I hadn’t really thought about it as such, but there is some satire swimming around in the mix. I certainly didn’t set out to include any, but ideas come with many threads. Just like life, there is sometimes laughter in the morning and tears in the afternoon – you never know what is going to happen. It’s beautiful to move through different moods and feelings based on the ideas that come along. The ideas inevitably string themselves into a whole so that there is some sort of balance.

It’s a perplexing film. What do you hope the lasting impression will be for audiences?

I’m hoping that they enjoy the ride and I’m hoping that their intuition kicks in, this machinery we all have for sensing things we aren’t necessarily able to articulate. Abstractions can exist in cinema – and that is one of its greatest powers, for me. I love the abstract feel of it and I hope that others do as well.

I cried so much during The Straight Story and The Elephant Man. Some of my reviews made me cry as well.

Where do you draw your ideas from?

Well, from my mind, I guess. But that’s not necessarily as simple as it sounds. The mind is a beautiful place, but it can also be pitch dark. How big the mind is, we do not know. Ideas sometimes come into my mind that make me crazy. I don’t know where they come from, and I don’t know what purpose they serve. Recently I have been thinking about ideas as fish, and that they are always swimming around us. Once in a while we catch one, and they pop into the conscious mind and explain everything to us. That’s a magical thing and we’d be nowhere without these beautiful ideas.

Do you ever cry at your own films?

I cried so much during The Straight Story and The Elephant Man. Some of my reviews made me cry as well. My editor will tell you I sit sometimes in the edit room and weep. Emotion is a thing that cinema can really communicate, but it’s tricky. Here, the balancing of elements once again is critical. A little too much of something and you kill the emotion, too little of something else and it just doesn’t happen. In The Straight Story the challenge was all about trying to find that tender balancing point.

Your involvement in every element of the film process is legendary. How important do you feel this is to the final product?

In film I feel that it’s just common sense that every element is critical to the whole. One has to work very hard going back, checking ideas and the feelings that come with the ideas, and working every single element to try to get them as close to 100 percent perfect as you can. Nothing in this world is perfect, but one tries nonetheless, so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is a magic that happens sometimes when each element is correct, and that’s what one works towards.

With beautiful corpses and lesbian sex scenes littering the film, do you think Mulholland Drive will make it onto screens in the US?

Film needs to show all aspects of life, so it will get by the censors, but it will be rated ‘R’. I’m okay with that. My take on censorship is this: everything should be allowed to be shown. The key is to let audiences know just how far a film is going. Then they can make the choice to go and see it or not.

People are labelling it as Film Noir. Are you comfortable with that?

There may be Film Noir elements to it, but I think that there are a couple of genres swimming about in it. For me, in fact, it’s a love story. It’s not like you start setting out to do a certain type of film – the ideas tell you what type of film it’s gonna be, and by the time you realise what that is, it’s almost done. It’s strange how films unfold as they go.

Are you in the arthouse or commercial film gang?

There’s room in the world for all kinds of cinema should all be available to the public on the big screen. At least in America, it’s harder and harder to see arthouse films. The cineplexes play the same 12 films across the country and the arthouses are dying. But things go in waves, and tomorrow it may be an entirely different story.

Which camp are your films in?

I don’t know – I guess I’m on the fringe, somewhere.

Credits

Words: John Dunning

Photography: Matt Jones, from i-D Issue no. 274 (The Wild Women Do, March 2007)