In most contemporary fables (and realities), the factory is the villain. It has dehumanized the worker, removed craft from craftsmanship, and created a standardization of goods that eliminates wonder from the lives of their final users.

I didn’t really expect an anti-industrialist screed at the Rick Owens show—I expected Radical Clothes for Radical People™—but Owens can’t help but do everything with purpose. (Radical People tend to be radical thinkers, after all.)

Backstage after his show, Owens was discussing this collection of “basics,” the original idea being a sort of capsule wardrobe that could fit into the Rimowa suitcases he launch in January. (Collab, obviously, now sold out.) “How do you industrialize something you want to be magic?” he wondered.

The answer is to make big statements through small, sustainable production runs. Audiences are wooed by Owens’ silhouettes—this season bum-revealing slit skirts, “dracucollar” jackets, rippling latex tunics, and spiked leather dresses—but it’s about more than just looks.

It’s in the way Owens works. His press release has become a list of primary sources and distributors. I’ll list them all:

Leo Prothmann, a London designer, made the leather chaps.

Victor Clavelly, in Paris, continued the spiky leather chain mail from the menswear collection.

“Parisian Rubber Mistress Matisse DiMaggio” designed the rippled rubber pieces.

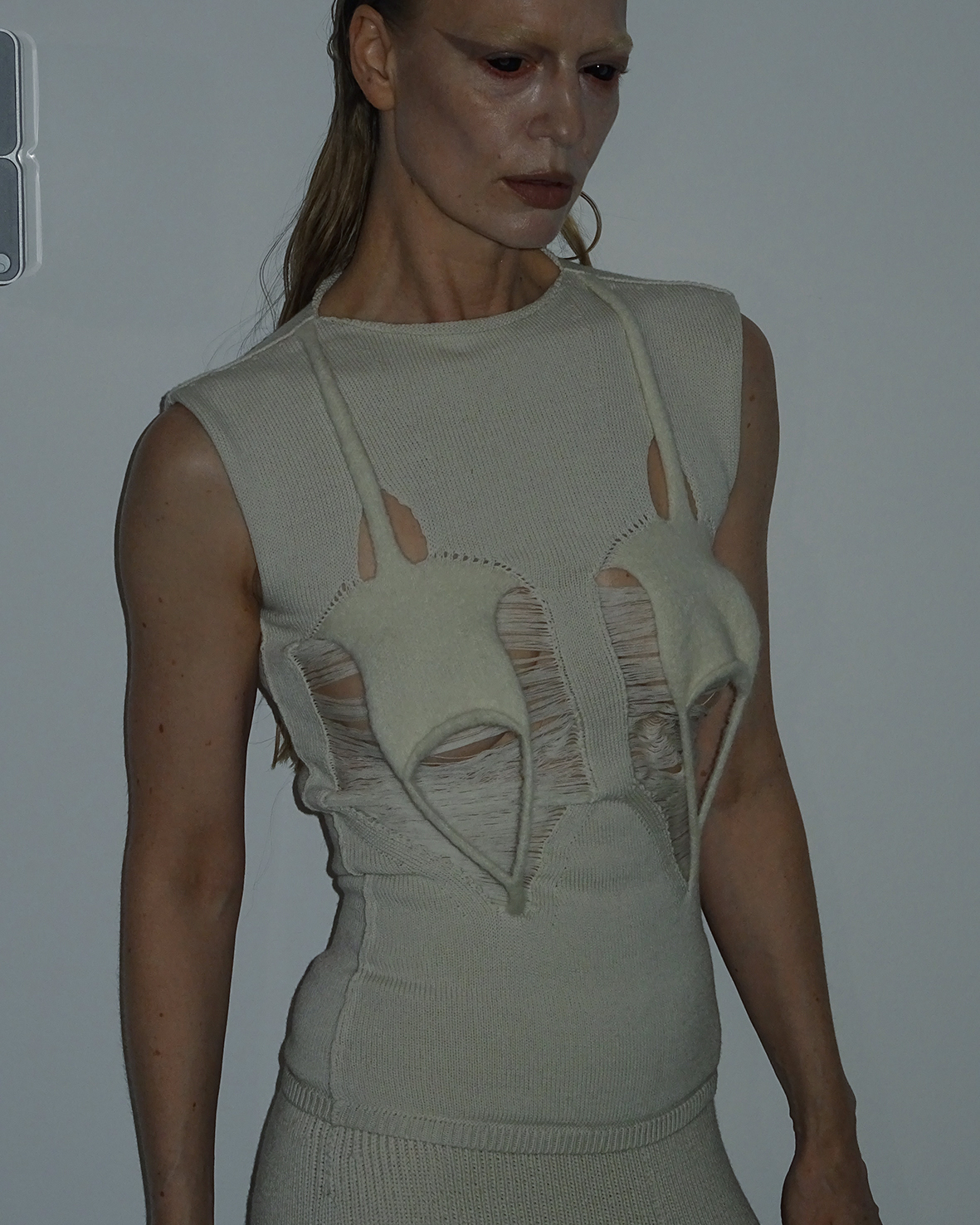

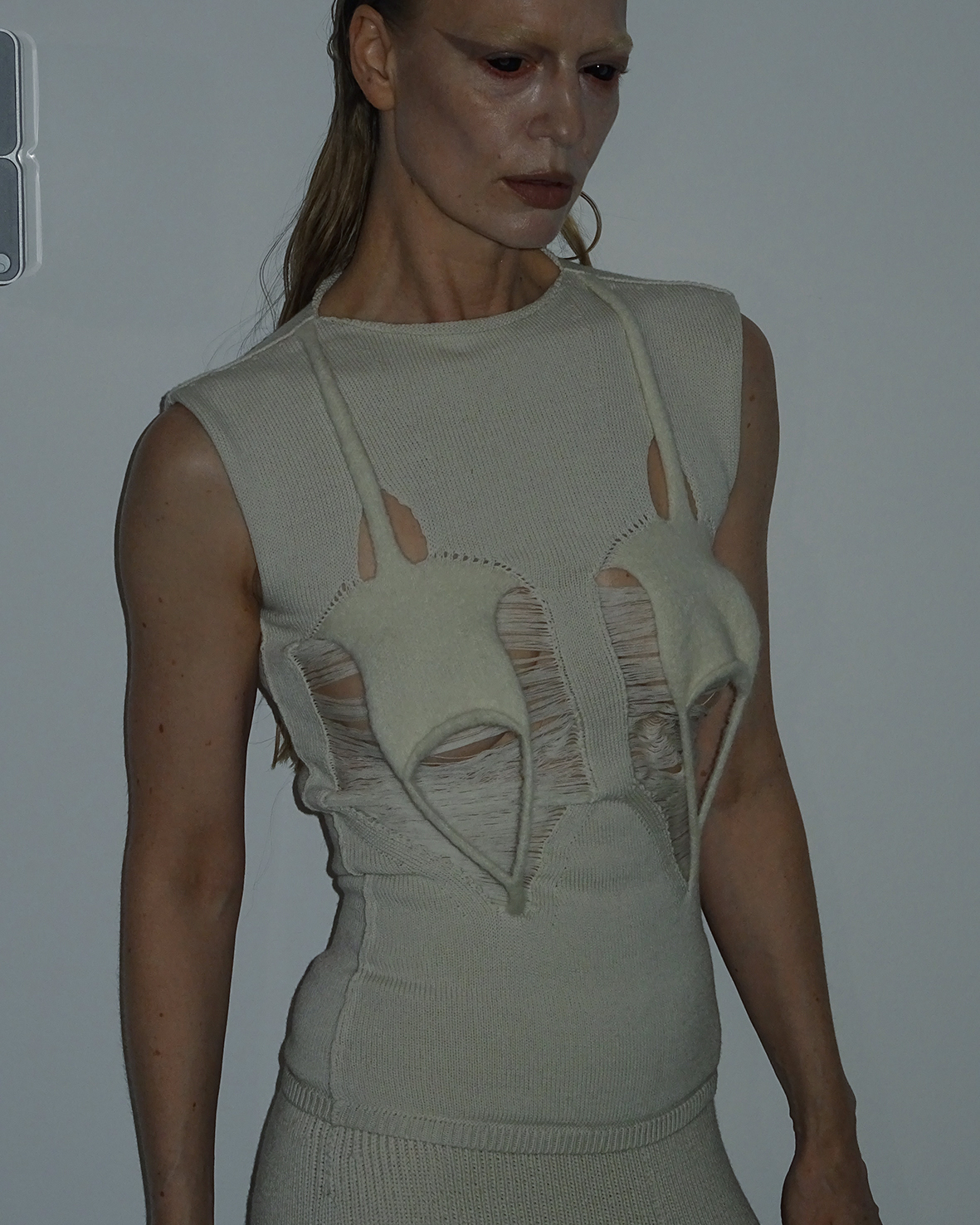

Tanja Vidic did the spidery knits.

Wool jackets come from RWS-certified wool in the Gifu prefecture of japan.

Only vegetal and natural tannins were used to tan those dracucollar leather jackets.

Heavy felt coats are made from sheep who went to Eton, or it’s “British wool board-licensed, non-mulesed British wool sourced exclusively from farms in the UK” that is washed in a “gentle and acid-free process that retains 95% of the water in a closed-loop system”

Pirarucu—Brazilian fish skins—are sourced to make the textured skin pieces.

Alligator pelts are “sourced responsibly across the USA”—ask Lana Del Rey’s husband about that I guess.

Bonotto, a textile manufacturer, helped with wool pieces.

Denim gets bathed in Veneto in a recycled water facility.

Another kind of denim is “14oz organic Japanese indigo slub denim woven in the Fukuyama prefecture by a mill founded in 1893.”

Everything else is made in Concordia, a factory Owens owns in a town that is erupting in his image. On the roof of the factory is a beehive and the honey is dealt to employees as gifts.

Nothing is mass at all about a Rick Owens show or collection except the interest in it.

Chappell Roan and Eartheater sat in the front row beside Vaquera designers Patric DiCaprio and Bryn Taubensee. Every member of the international fashion press corp pushed into the room and every fan of the brand in a 50-mile radius seemed to be pressed against the Palais de Tokyo’s giant glass windows. Each of us in the space are asked to consider how much thigh to show, how much neck to hide, how spooky—like those high collars—or how sincere—like a Greco-Roman toga draped cloak—we should be. Owens proves it all works better as a community. His is a factory of familiarity, where all are welcome.