On a stage sandwiched between the Literary Criticism section and the Poetry books, journalist Alex Vadukul looked out at the crowd and declared, “We’re in the presence of greatness.” He could have been referring to the audience or the readers of the evening’s programming, but that night, he meant Gay Talese.

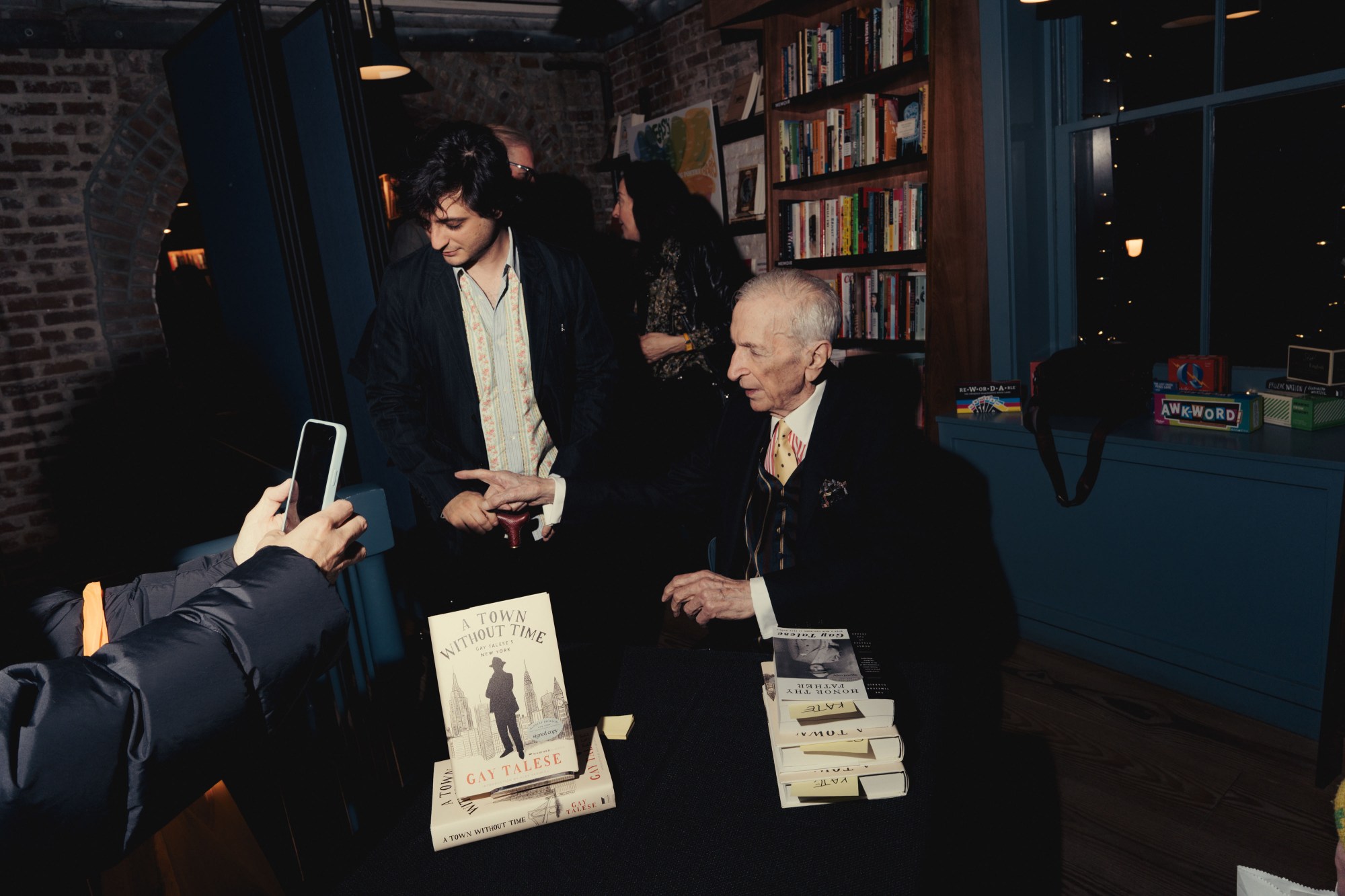

On March 7th, over a hundred of New York’s most influential editors, writers, and media personnel packed into McNally Jackson Seaport’s claustrophobic upper-floor space. They were there to celebrate the launch of A Town Without Time, a substantial new collection of Talese’s city writing.

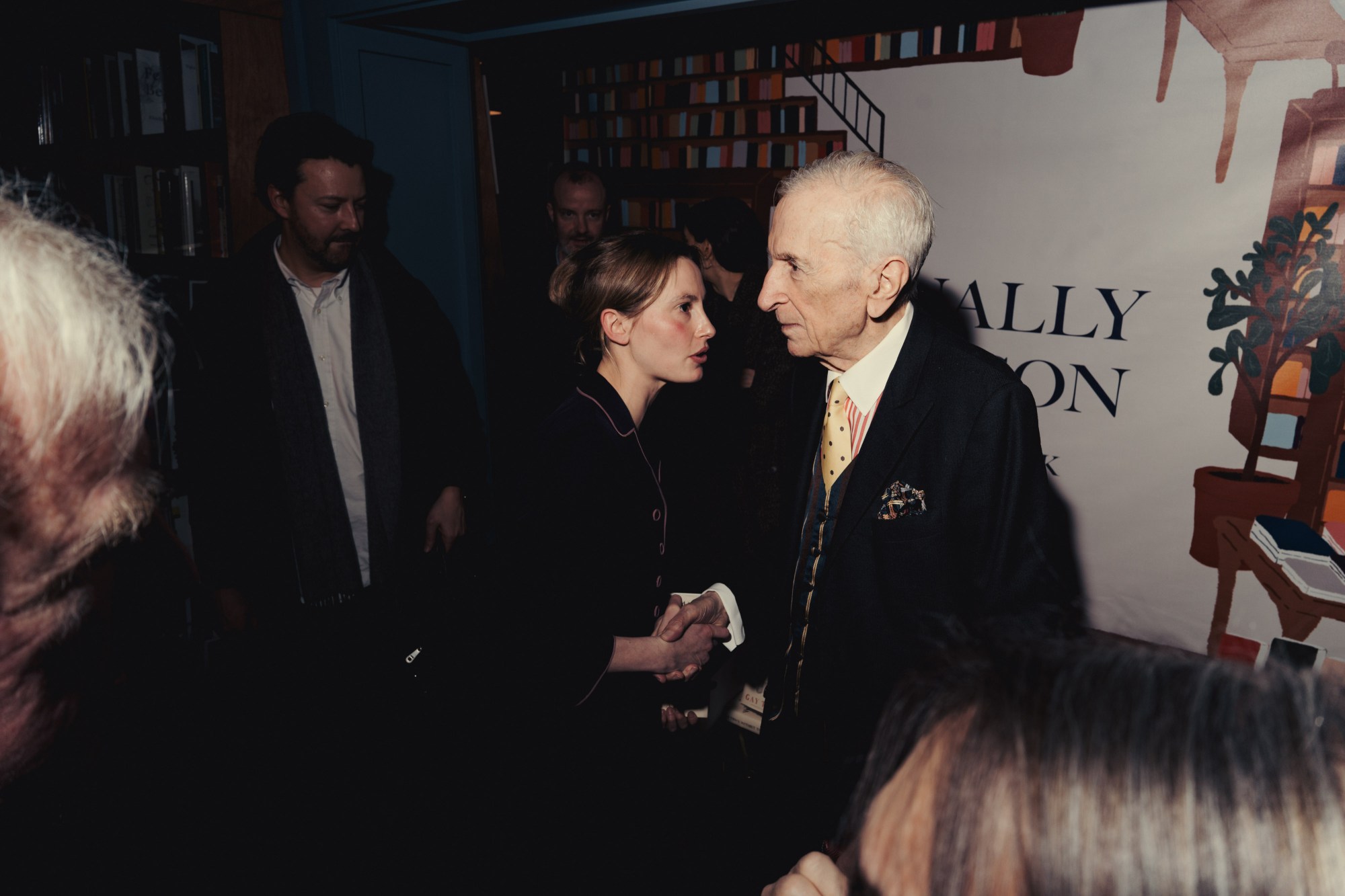

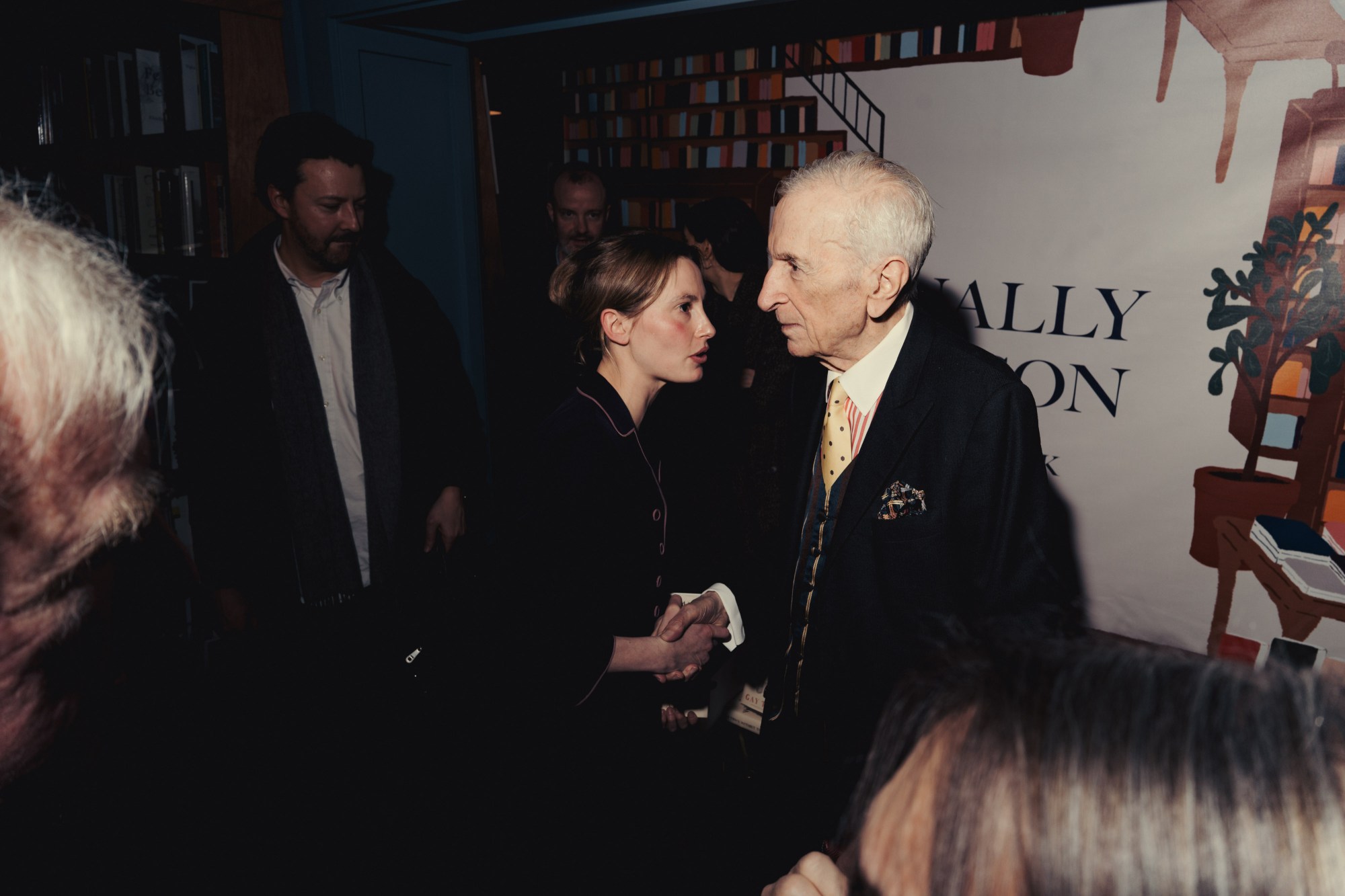

For over six decades, Talese has chronicled the city. The suave 93-year-old is a celebrity in the literary world and dresses the part, seldom seen outside of a three-piece suit. It is impossible to write about the history of journalism without an aside on Talese’s hand in creating New Journalism— an approach that uses the creative elements of fiction to tell a better story—and the impact his work has had on countless others. Many of those people were in the room—a who’s who of reclusive editors, star writers, and rising talent drawn out by the rare chance to hear Talese speak. Among them: Carolyn Ryan (NYT masthead editor), Bill Buford (pioneering editor of Granta and former fiction editor at The New Yorker), Jon Caramanica (NYT), Dodai Stewart (NYT), Rukmini Callimachi (NYT), Jim Windolf (NYT). Writers taking a break from deadlines included Sadie Stein, James Traub, Gideon Lewis-Kraus, Emma Goldberg, Nick Confessore, Anna Kode, Michael Daly and Mark Jacobson. Attendees known for paving new routes in the field were similarly rapt—like The Drift’s Krithika Varagur and Kiara Barrow, or writers Camille Sojit Pejcha, Cara Schacter, Jay Bulger and media strategist and speechwriter Alex Levy.

After a brief series of readings by Air Mail’s Graydon Carter, NYT’s Guy Trebay, and actress Annie Hamilton (reading an invigorating tale about the nocturnal lives of alley cats that Talese wrote when he was just 27), Vadukul and Talese sat down to discuss everything one would want to know about the golden age of journalism—namely, what was it like to have drinks with Susan Sontag. It turns out… it was just fine. Other topics covered: how fantastic having a month-long lead at Esquire was, how he used to remove his name from pieces if he didn’t like the edits, how writers need to dress better (I’ve been saying this!), how his eldest daughter, Pamela, was conceived in actor Peter O’Toole’s guest room, and how, currently, The New York Times (Talese worked at the paper of record for years) is too reliant on tape recorders and publishes too many Q+As because they’re afraid of being sued (this earned sniffs from the Timesmen in the room).

In some sense the nature of a city journalist is a lot like that of the metropolis they report on. People make an impact one day, and by the next news cycle, they’re irrelevant. Trends come and go. Restaurants open to fanfare and then shutter. Will the journalist be just another thing that once existed? In the case of Talese, he has outlasted it all and become part of the very fabric of the city.

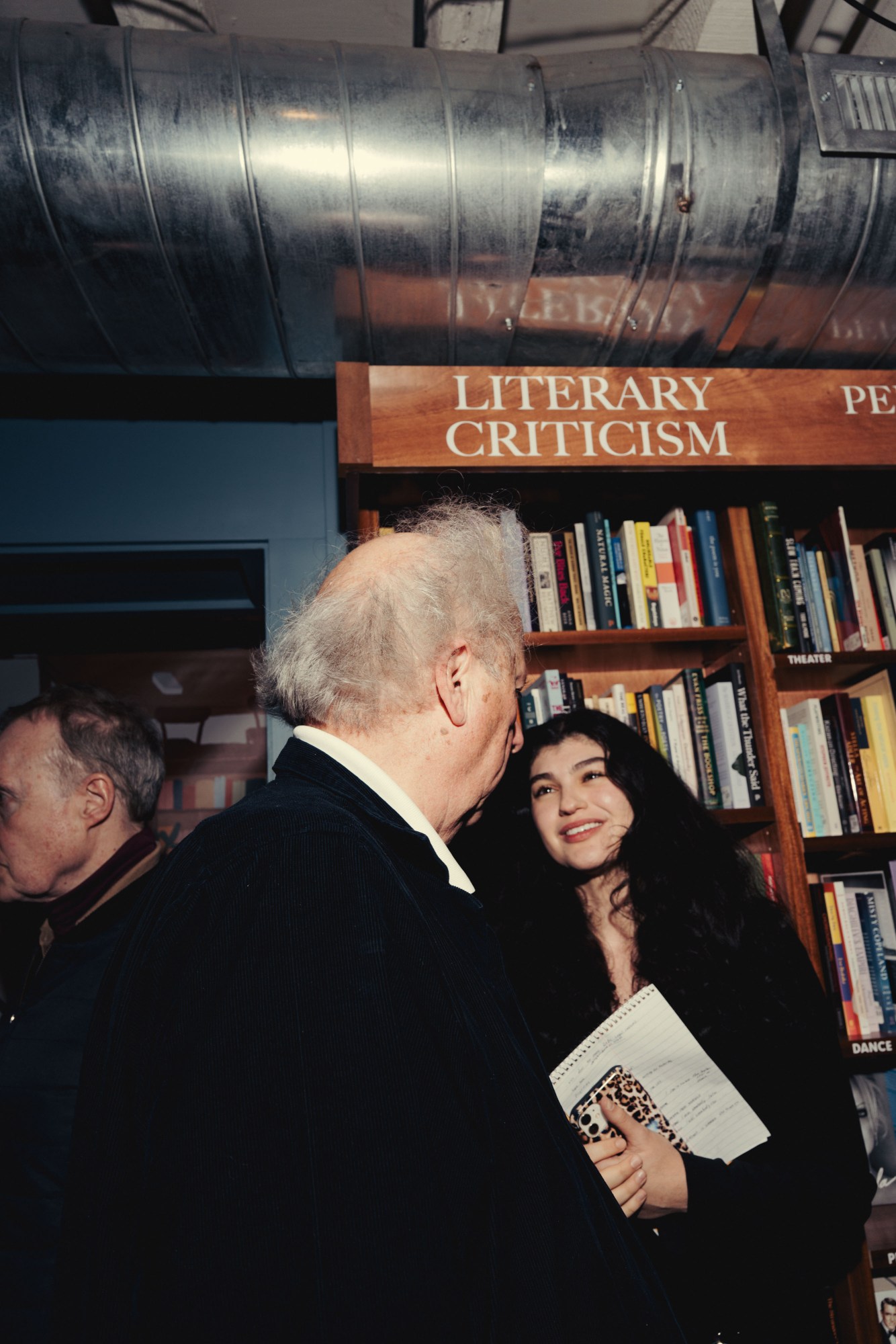

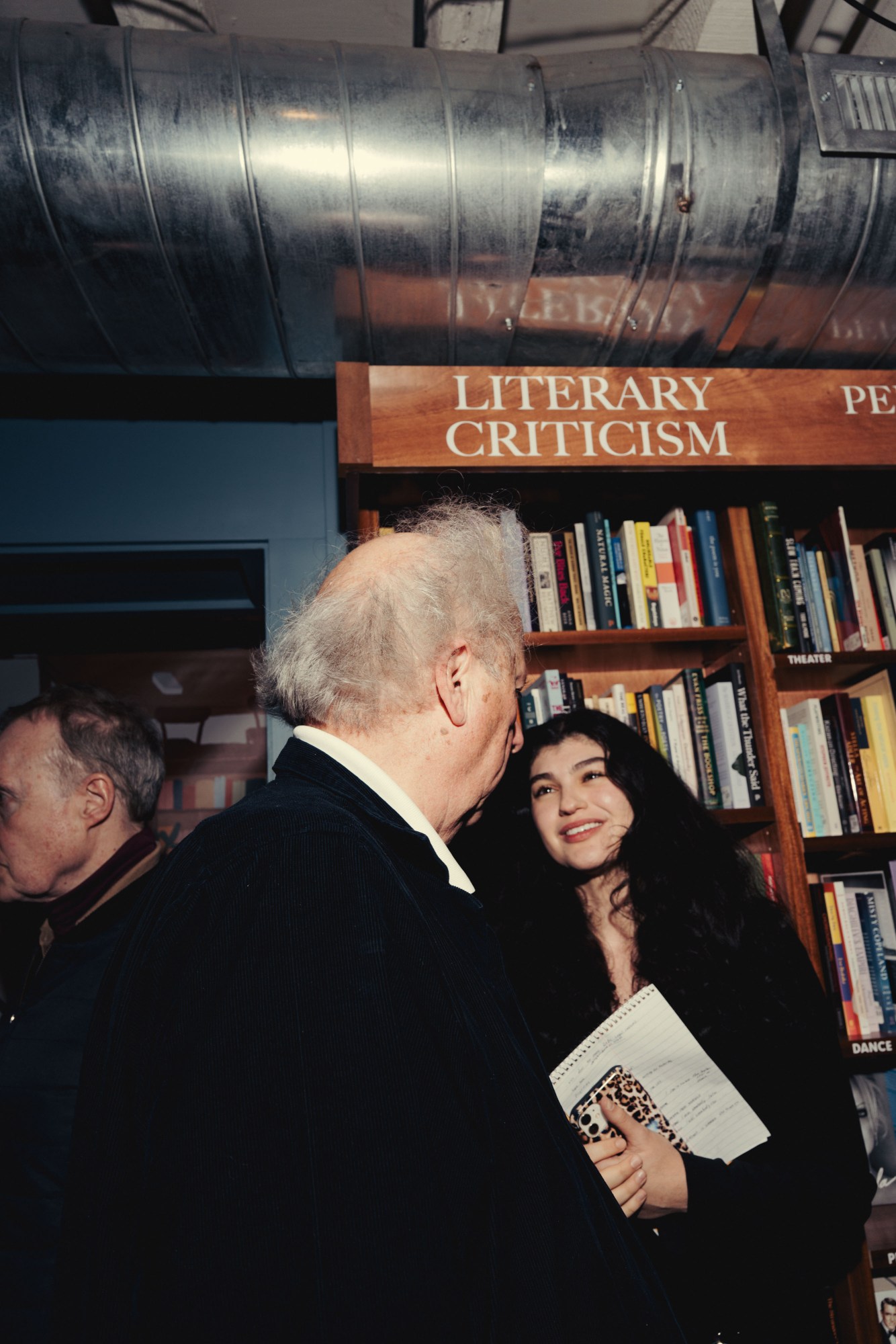

The night was as much about the relationship between Talese and Vadukul as it was about Talese’s longevity and dedication to craft. Vadukul, himself an award-winning journalist at NYT, wrote the foreword to the book and helped organize the evening. He read Frank Sinatra Has a Cold in his undergraduate journalism class at The New School and was immediately smitten with the writer. Vadukul told me, “I became a mini Talese scholar.” He took advantage of a class assignment and reached out to interview his idol. Though Talese famously has never had a cell phone, Vadukul’s teacher fortunately had his landline, a number that had been passed around the journalism community for years. Vadukul went over to Talese’s Upper East Side townhouse for the interview and they’ve maintained the relationship ever since. As Talese cheered from the side, Vadukul built a career, “My little stories turned into bigger stories and bigger stories. And I would come to him for real advice, problems I was having, decisions I should make.” On stage their mutual admiration was clear and very sweet. That affection diffused through the event, imbuing even the biggest and most successful literary curmudgeons with conviviality. Here was a room of people who had read each other for years, edited each other, competed with each other, and yet, what they all have in common is the love of journalism. It was a celebration of why we do what we do, and how we do it.

The industry currently faces great challenges. There is less money, less critical thought. Everybody with a phone can capably disseminate information, and everybody with a computer is a writer. Who even has a mentor anymore? Hangouts like Elaine’s have long been closed. Talese is correct—we are too reliant on recordings and have lost the ability to hear and reflect on what we listen to. What, then, separates the journalist from the layman? Is it institutional backing, or is it perspective? The questions New Journalism asks of a writer are ones particularly attuned, even anticipatory to these problems. Talese described his calling to the vocation: “I knew I was somebody. I also knew I was somebody else.” And in that awareness of friction—that self-imposed consciousness of distance—is greatness. This may have been the final gathering of the greatest generation of journalists. They embody the perspective that comes with having a mentor, studying history, and being dedicated to their craft for as long as they have. Sitting in McNally Jackson Seaport, in a building built in 1811, feeling the cohabitation of past and present, the magnitude of the evening was apparent.