The word joy gets overused in fashion. It’s often code for bounce, ruffles, and obvious charm. Guillaume Henry’s version is less about exuberance and more about precision. At Patou’s Spring 2026 show, titled Joy, the mood was restrained but luminous. There was softness, yes, but here, Joy came with edges.

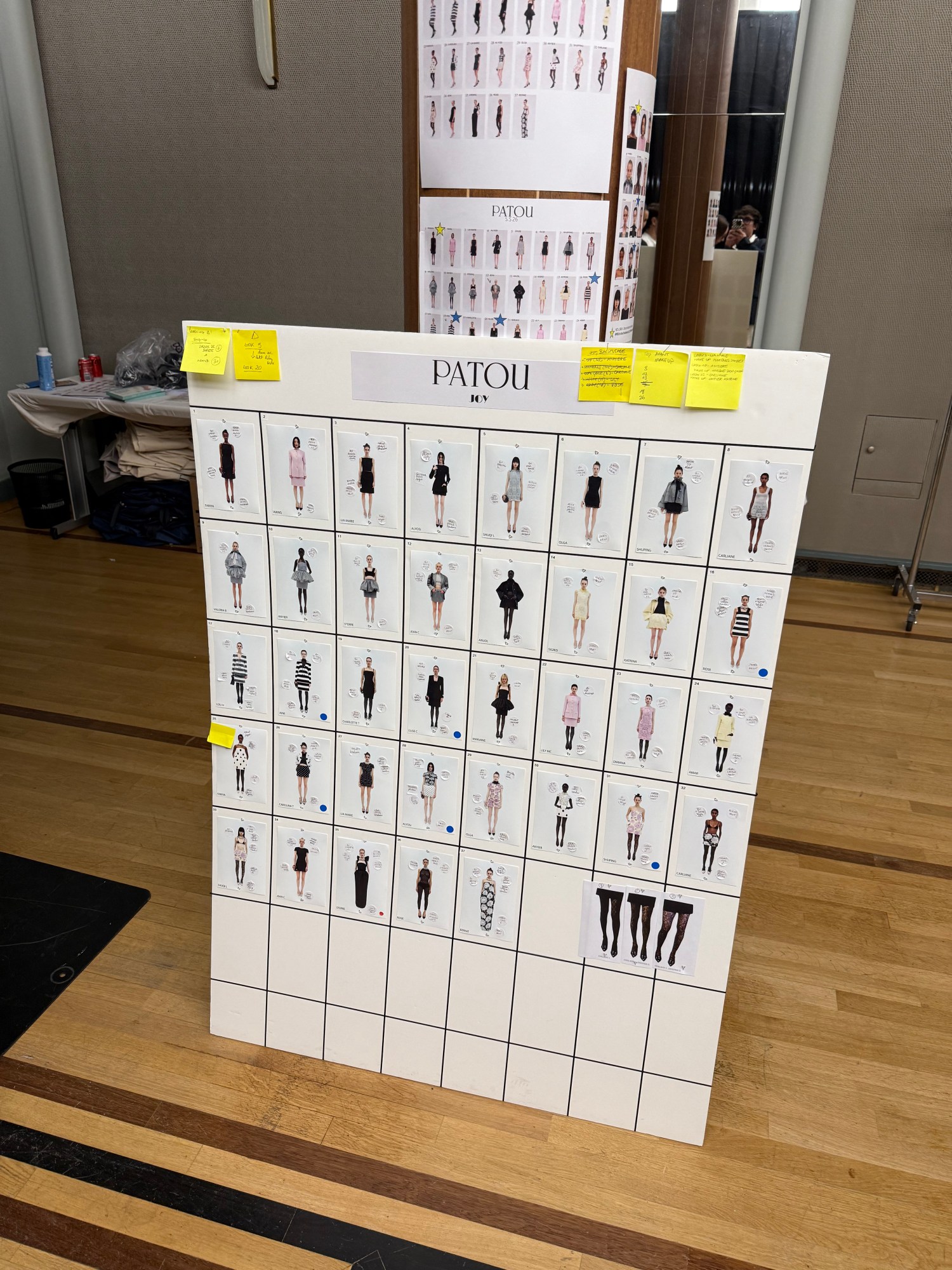

The day before the show, I visited Henry at the Patou atelier. He was fitting a sleek black ankle-grazing dress on a model—minimal in shape, but technically exact. Around him, the studio buzzed with quiet focus. When we spoke, he was composed and measured. But as he started pulling pieces from racks, pointing out prints and fabrics, his tone became dreamier. “I felt for silver,” he said. “I felt for light. I felt for a smile.”

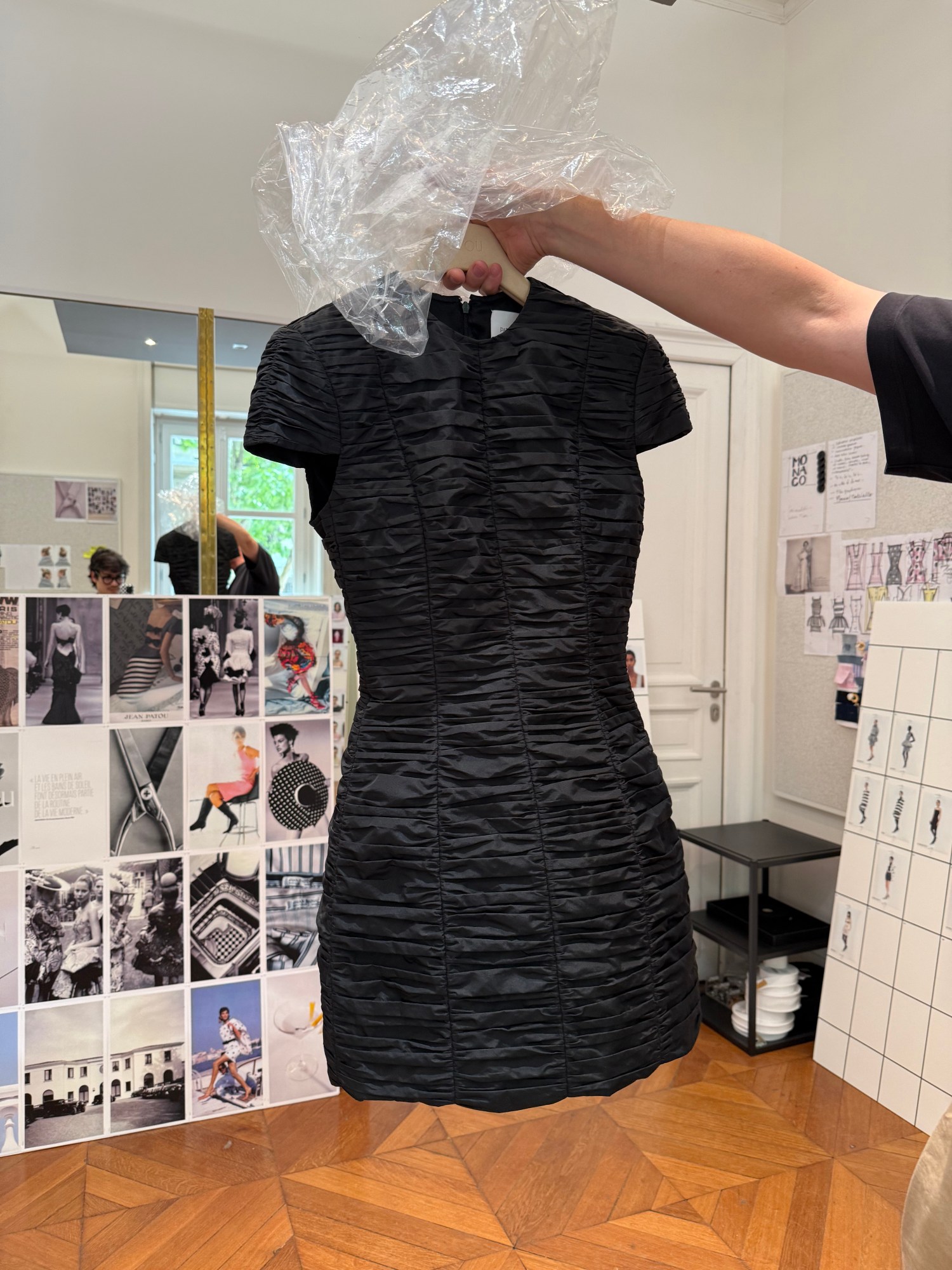

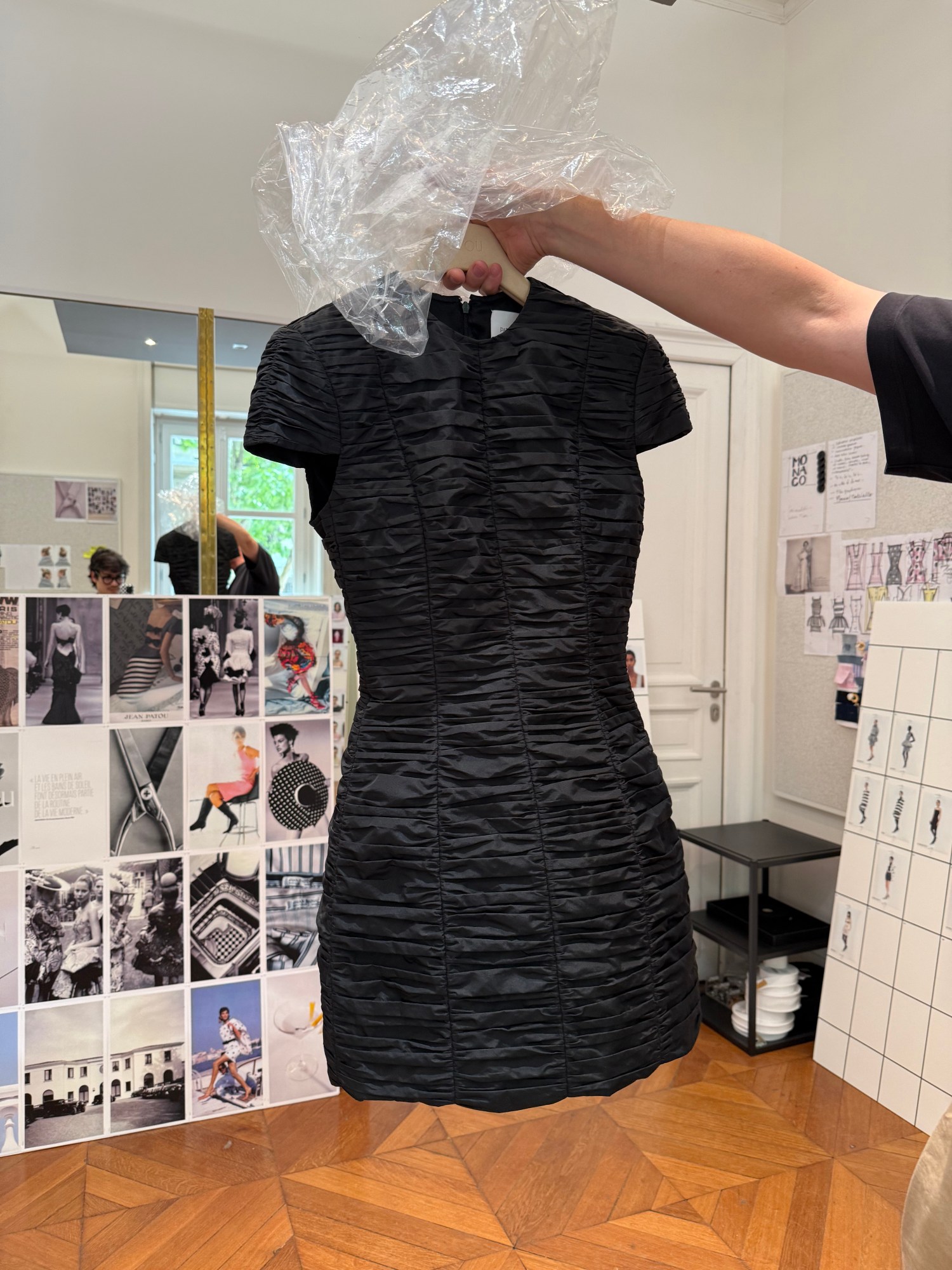

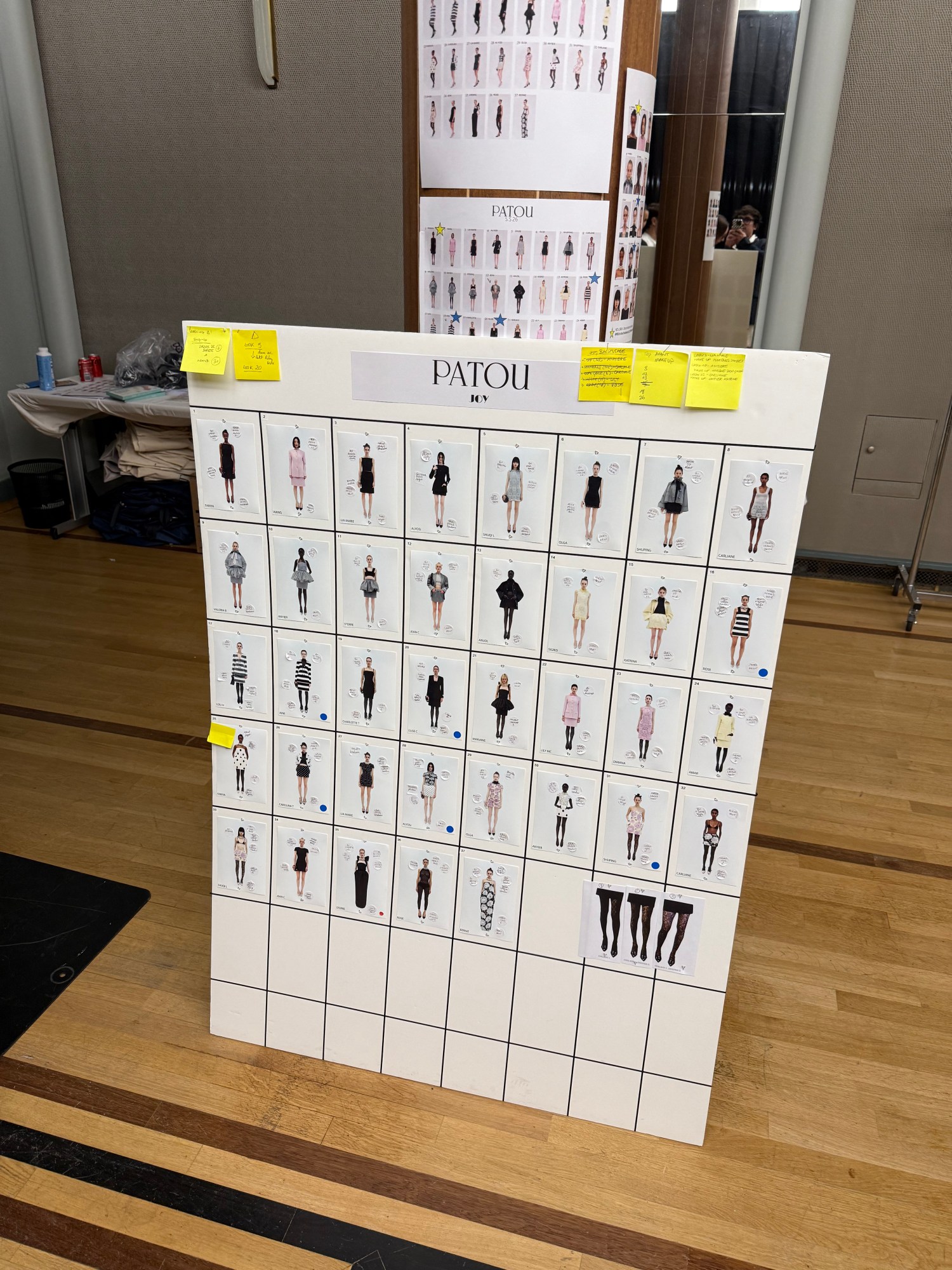

That smile took many forms. The collection began with sculptural tailoring in pale gray and soft white, occasionally edged in silver hardware that echoed nautical closures. There were ruched jersey dresses cut close to the body, styled like swimwear but built with couture-level discipline. A signature bustier dress looked poured on, holding its shape like a vase even in motion. “I wanted each silhouette to feel like an object,” Henry told me. “Constructed, but easy to understand.”

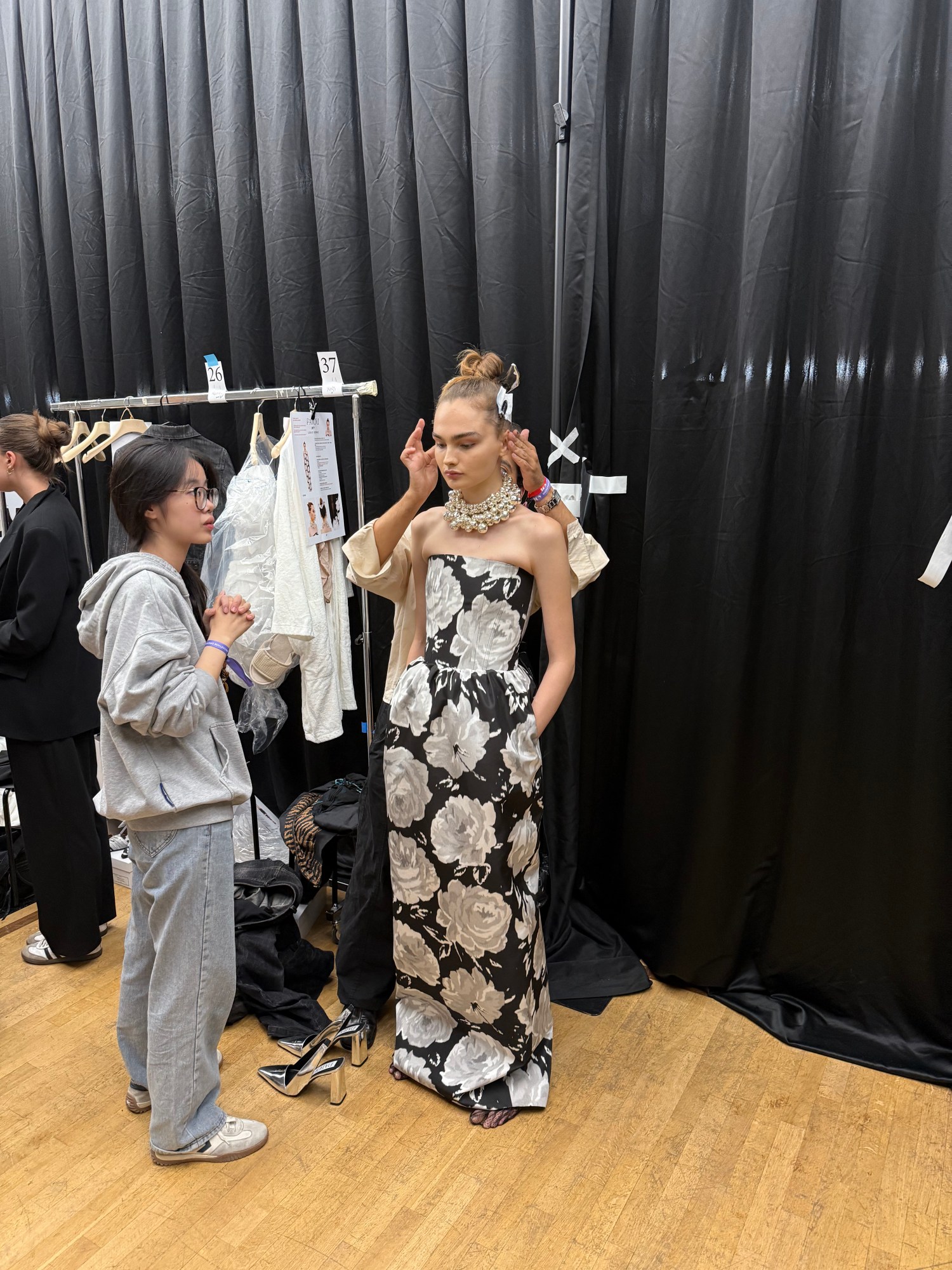

Florals arrived with purpose. Peonies—Jean Patou’s favorite flower—appeared as prints and lacework, not as decoration but as graphic structure. One dress layered ruched taffeta under sheer lace, creating a subtle topography. Another featured a floral motif engineered to align perfectly at the seams—more architecture than embroidery. “I don’t like when things look too emotional,” Henry said. “It has to be precise. Subtle.”

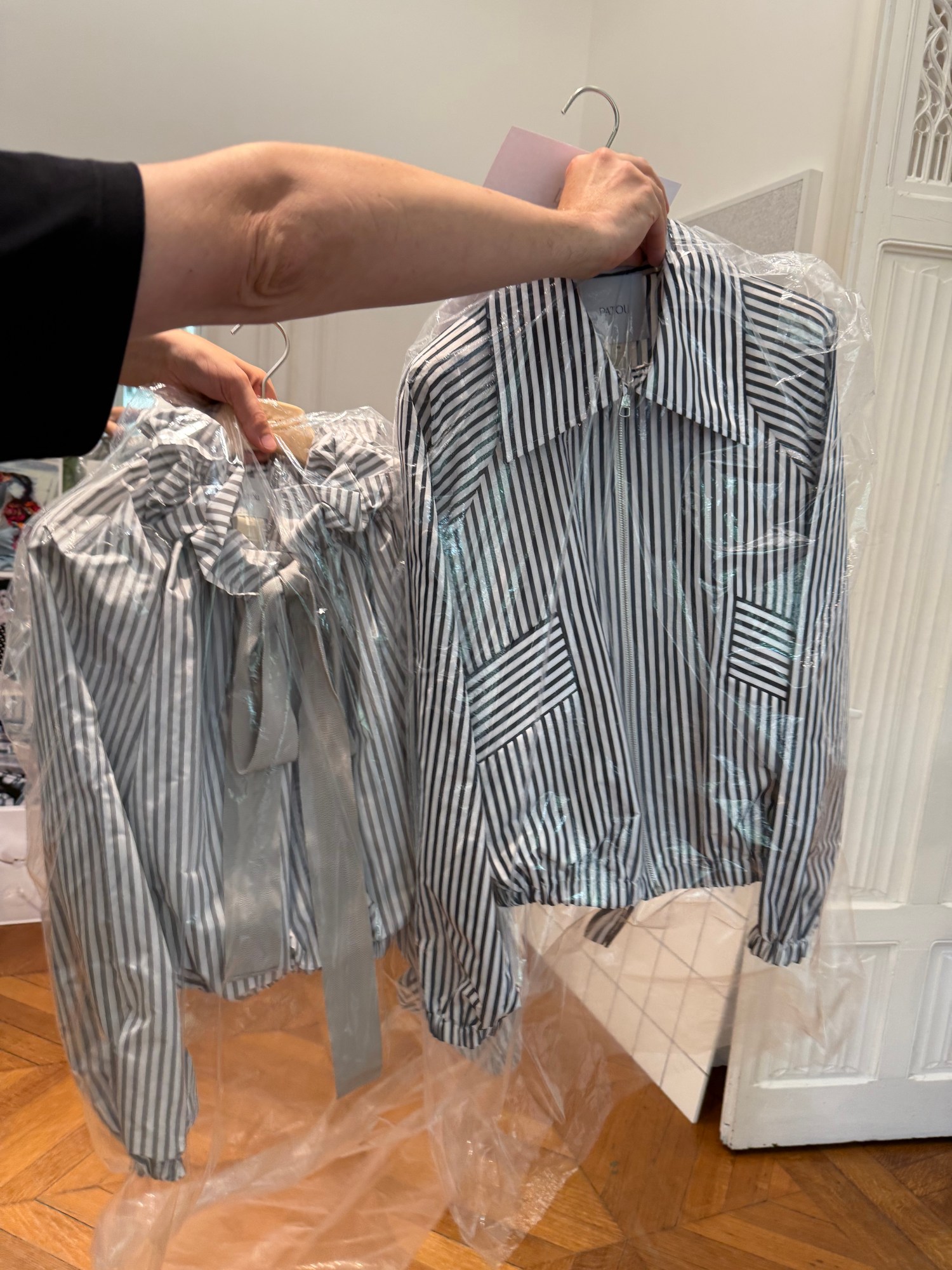

That word, subtle, came up often. The collection plays in the space between day and night, sport and couture, softness and shape. A body-hugging jersey dress could read as athletic or formal depending on the shoes. A suit in soft lemon yellow felt breezy and strict at once. Even the color palette played it cool, including muted grays, soft whites, mixed neutrals, with occasional pinks that looked closer to mauve or washed lavender.

References were present, but never heavy-handed. There was the ghost of Art Deco in the collection’s geometry. Echoes of Patou’s own 1930s house near Cannes, with its clean lines and sea-facing symmetry. There were also flashes of the 1980s, nodding to Christian Lacroix’s exuberant era at the maison, but filtered through Henry’s lens. “I like contrast,” he said. “If something’s graphic, I add fantasy. If it’s soft, I want structure. But never too much of either.”

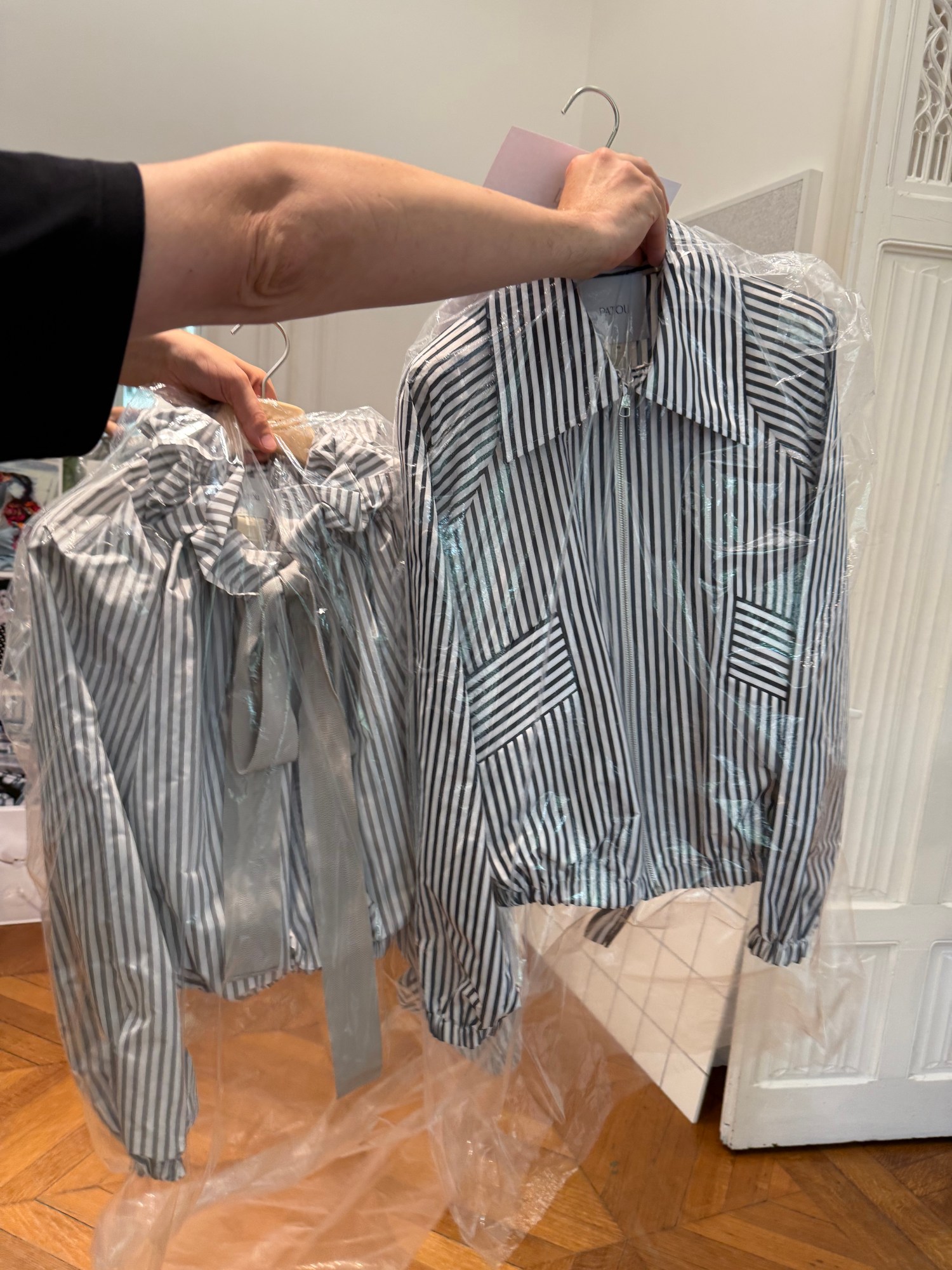

That sense of control extended to fabrication. Most materials were recycled or organic, but nothing shouted its sustainability. A recycled polyester jersey dress had the sheen and weight of liquid metal. Crisp cottons were mixed with lace to create volume without weight. Even the most intricate pieces, like a ballooning skirt in layered taffeta, felt engineered, not indulgent. “If it looks too difficult, I stop,” Henry said. “I don’t want to show the pain.”

The next day, I arrived at the show at the Maison de la Chimie, a quietly grand building tucked just off Boulevard Saint-Germain: marble staircases, wrought iron balconies, historic grandeur, and the kind of gentle light that makes clothes look even better in person. It felt more like a private club than a runway venue. You could imagine Joy living here—someone stylish, subtle, always slightly out of reach.

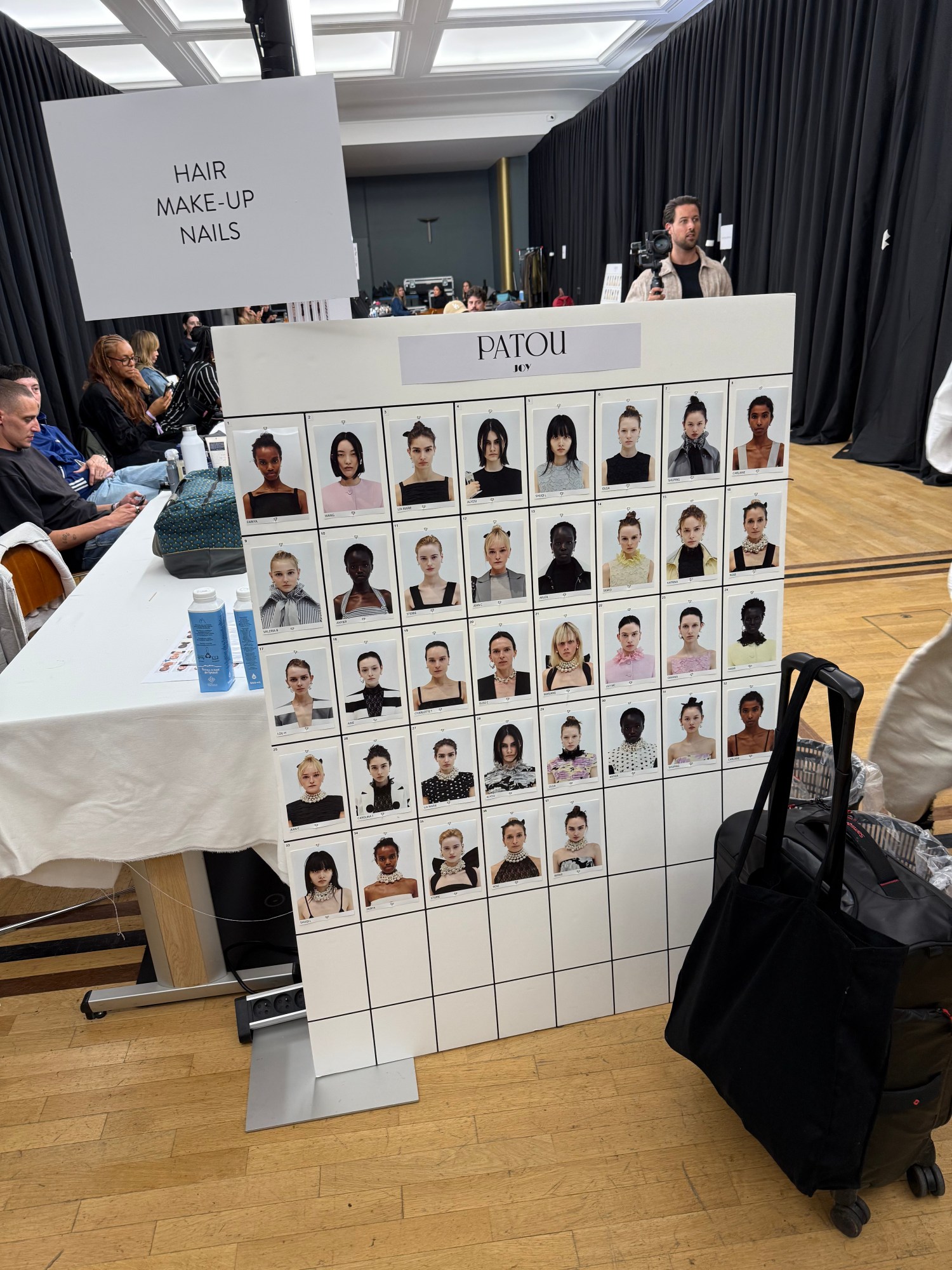

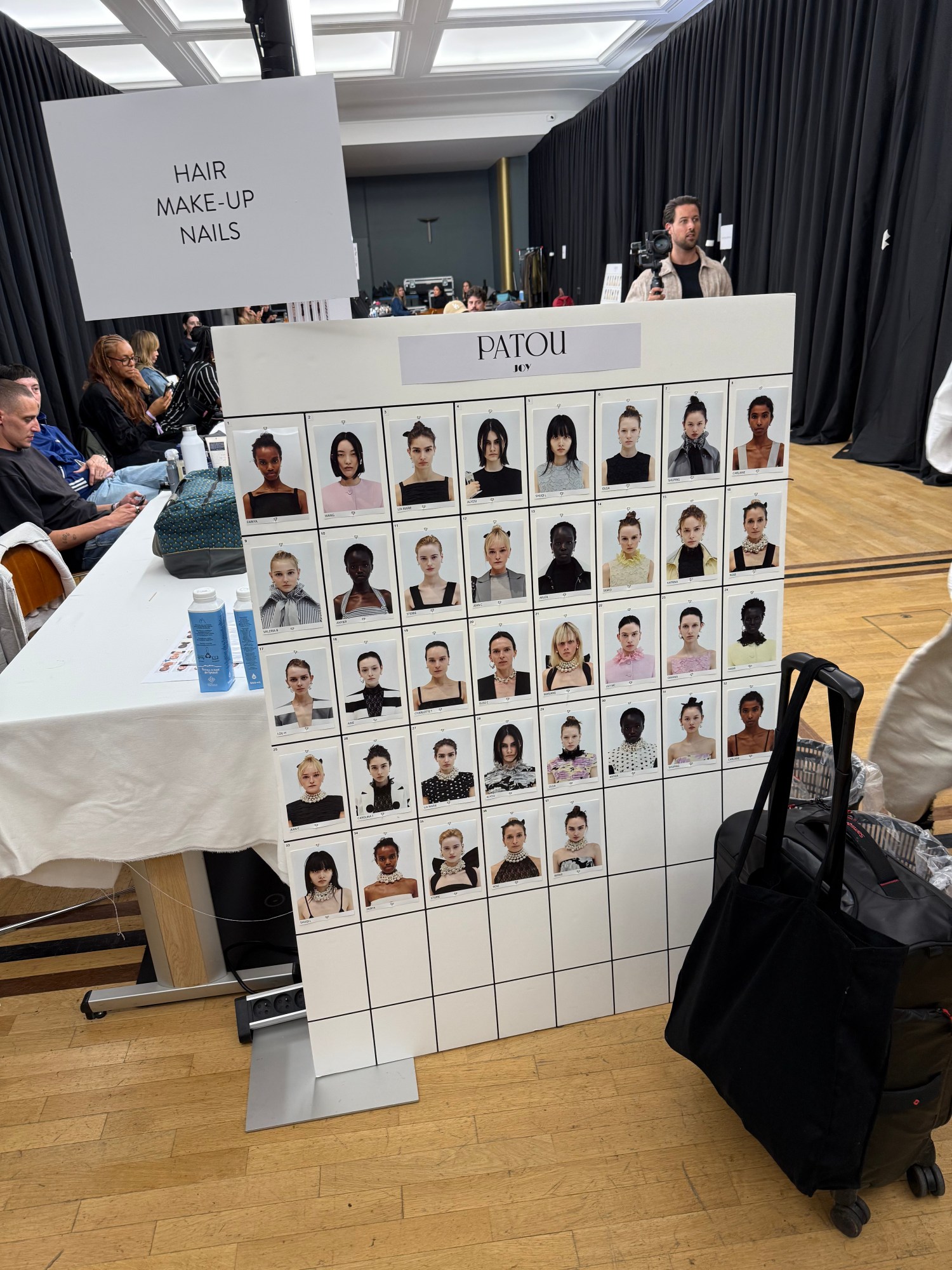

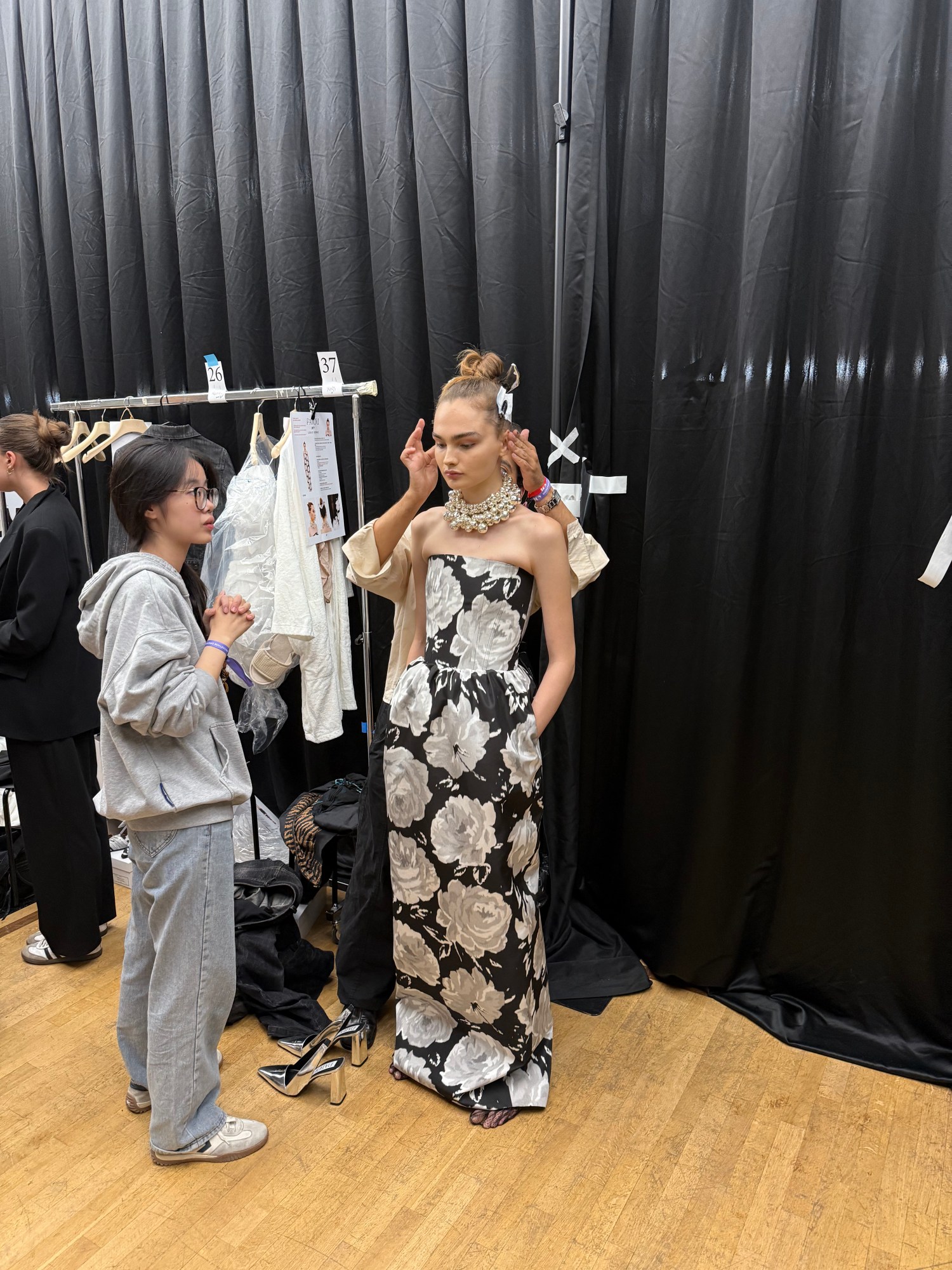

Backstage before the show, the models lined up in a mix of taffeta, lace, and ruched jersey, all high cheekbones and perfect posture. In the main space, lemonade was served in martini glasses—a charming, slightly surreal touch. I could’ve done with something stronger, though. Then we sat. The music began.

The girls glided out, one by one, moving with a kind of quiet certainty. Each look held its line. The mirrored heels clicked softly on the parquet floors. Peonies printed on engineered panels, structured dresses floated just above the ground, minis sculpted so cleanly they looked cut from air. It wasn’t loud. It didn’t need to be. It was beautiful. But I already knew that.