This story appears in i-D 375, The Beta Issue. Get yours now.

written by KACION MAYERS

photography FRANCESCO NAZARDO

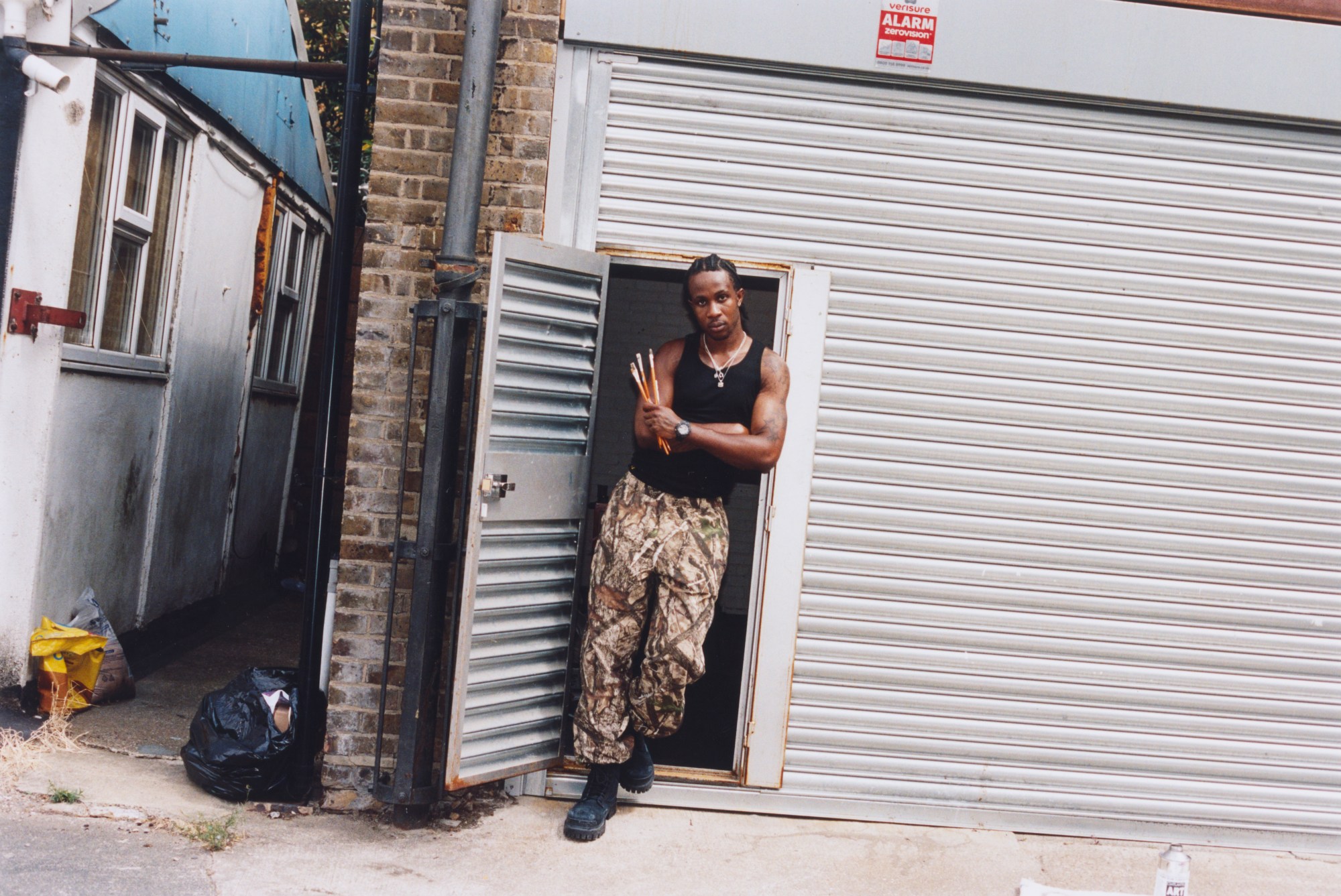

Behind a nondescript, wicket-doored roller shutter in a warehouse park southeast of the Thames river, Leonard Iheagwam—the artist known as Soldier—is in his oblong studio. This is where you’ll almost always find him, sitting at a desk cluttered with miscellaneous objects. At first, a quiet and mysterious character who, once comfortable enough, promises a torrent of chat that is both unexpected and endearing.

Soldier is an Aries, with a Scorpio ascendant, and a Taurus moon. He knows this, he tells me, because a few christmases ago “I got really into star signs. Now, it’s become a big part of my conversations.” According to a quick Google search of the signs, this means he’s very energetic, confident, dynamic, not afraid to take risks, loyal, intense, and mysterious. It’s that last characteristic that is often first to surface, but he finds pockets in his life where his other facets can be expressed. Boxing and Muay Thai are frequent pastimes. A 3km morning run followed by a post-run workout are typical starts to his days. He’s really into films at the moment, his favourite being Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo ’66, and he’s excited to check out James Gunn’s new take on Superman later this evening.

“I am a recluse in a way,” he begins, in a projectile train of thought that can routinely give his publicist a jumpscare. “Sometimes social interaction gets to be a lot. I spend most of my time painting. A painting like this takes a lot of time,” he says pointing to our left, “at least five hours.”

On the wall is a work-in-progress portrait of Olivier Rousteing immortalised mid-jab—his braids falling past his shoulders, arms up, and a single boxing glove pressed to his eye. A single colour acrylic underpainting is used to establish the values before the full spectrum of colours are applied. He was on set with the Balmain creative director for his cover shoot, chiming in when photographer Francesco Nazardo captured the winning shot. “Olivier is amazing. He had so much energy. He just gets it,” Soldier tells me.

“The reason I painted that picture,” he offers, “was that one of the first realistic portraits I did was of a Nigerian boxer named Dick Tiger. He was an underdog who came to London and died really young. When I saw Olivier, who is also a boxer, I saw that connection.”

Today, he’s painting Rousteing, but back in November 2019, Soldier, alongside Slawn and Onyedi of his skate crew Motherlan, were i-D cover stars themselves. Back then, London was a hopeful dream for the trio, a glint of possibility fueled by the unwavering support and mentorship of figures like Grace Ladoja, Alex Sossah, Teezee, and Seni Saraki.

“It was hell, I can’t lie to you,” he recalls of that time in Lagos. “Because I ran away from home at that time. I was so confused about everything. I wasn’t speaking to my parents. I was on the streets, homeless, going from house to house.” Lagos is a city defined by its hustle as much as its hypocrisy, its unrelenting perseverance as much as its debilitating corruption. And where there are cracks in its foundation, there is also resilience and bright-eyed hope in the young people who often fall between them. One of the reasons he took the name “Soldier” is that it derives from Nigeria’s law that bans civilians from wearing camouflage in public, with violations that result in fines and potential imprisonment. The irony of him sitting before me in camo cargos and an oversized camouflage Supreme Spring 2014 Championship football jersey does not miss me.

His father’s evangelical strictness, it turned out, simply couldn’t fathom the future his son would inevitably carve out. But for Soldier, hope bloomed in the bonds he forged with Slawn and Onyedi, and crucial mentorship arrived from Jomi Marcus-Bello, founder of the Nigerian skate brand WafflesnCream (or WAF). That innate hustle saw him seize any and every opportunity, a relentless drive to escape the cracks that swallowed so many young people in similar situations.

“In Nigeria, there are two kinds of people: the extremely rich, and then the others,” Soldier says as a matter of fact. “For the others, it’s a country that doesn’t work and is super corrupt. It feels like your back is against the wall, so you have no choice but to find a way to do it. That’s why a Nigerian person is the ultimate hustler. When you wake up in the morning and have no safety net, you become a different breed of human.”

“I want to destroy the model of the art world that is very not inclusive.”

Soldier

Since landing in London, Soldier has been anything but idle. He’s gone on to collaborate with an enviable roster of names: Nike, Duke + Dexter, Louis Vuitton, Aston Martin F1, Timberland, Hublot, KFC, Marni, and Lewis Hamilton’s Mission 44. He also opened his third solo exhibition, Black Star, at Kearsey & Gold. He remembers coming into a spirited, creative scene in London, reaching the end of its era. The Scotch of St. James—a dim, Mayfair hotspot tucked into a cobbled cul-de-sac—was charted territory. In those days, any of the random bars littered along Dalston high street offered unlimited possibilities in the proceeding hours. Same went for Shoreditch. This was the case until the compass begun to swing further east, and even north. Especially as nightlife came under siege: clubs shuttered, new builds encroached, and then, of course, the pandemic hit—by this point, he hopped between more intimate spaces friends held in their homes. He hung out with Onyedi, Slawn, and Mowalola.

The city crackled with an infectious spirit—a force he still carries with him today, even if, in his opinion, London’s energy has since shifted.

Nowadays, Soldier observes a London creative scene that feels less open and more fatigued. While he sees vibrant networks of mutual support thriving in places like New York, he believes that London tends to foster a more individualistic approach. “People don’t really support each other in London. That’s my perspective,” he starts before reaffirming, “but I would say there’s a renaissance happening in London as well. I feel like things are changing.”

Our conversation drifts to the pervasive nostalgia among young people, a phenomenon that, I suggest, stems from a perceived lack of positive or hopeful futures. There is a habit of looking back at the good times once promised but seemingly robbed from them, often stifling a future-facing creative vision. “You’re right,” he readily agrees. “In the ’20s, people were looking forward to industrialisation. People were thinking, ‘Oh my God, in 2050, we’re going to have flying cars.’ People were making all these bold ideas. Now we’re here and the future is not as glamorous. I feel there’s going to be a new thing that happens, but it’s going to be hyper-futuristic. I feel like what’s next right now is new frontiers.” We both agree.

However, with a cheeky eye-roll and knowing smile, he readily admits that the past also informs him and his work. He rattles off names like Da Vinci, Jeff Koons, Rita Ackermann, Frida Kahlo, and Basquiat—not just for their art but, as he distinctly points out, “because of the lives they lived.” He elaborates: “You have to be a really special human being to be like, ‘I want to actually make a job from painting and creating things.’ I get really inspired by the people who came before me.”

In turn, a new generation finds its inspiration in Soldier himself, alongside his contemporaries. Witnessing their ascent and ability to carve out a name for themselves in an industry that often feels impenetrable has become a communal win.

“I would say we bring a newness; a new way of thinking. A freedom to make,” he states. “My stories are very heavily charged with how I feel. I don’t come from a very privileged background, so my work is to advocate for those people. I want to tell stories that can stand the test of time. I want to destroy the model of the artworld that is very not inclusive.”

In his 2019 interview with i-D, where we first met Soldier as a pivotal force reshaping Lagos skate culture, Grace Ladoja once asked him about his dreams, “I want to be able to make some crazy shit. Do a collaboration with Apple. I want to see our logo on the side of a plane.” Today, his face settles into a mixture of awe and contentment. “Everything I said, I’m actually doing,” he affirms, though the goalposts have shifted. “Now I’m more conscious of my thoughts and what I think. I want to connect more with people. I want to inspire more people. What’s the word? Altruistic!”

grooming DANIEL DYER USING R+CO & DR. NATASHA COOK

production THE MORRISON GROUP

post production OFFICINAOTTO