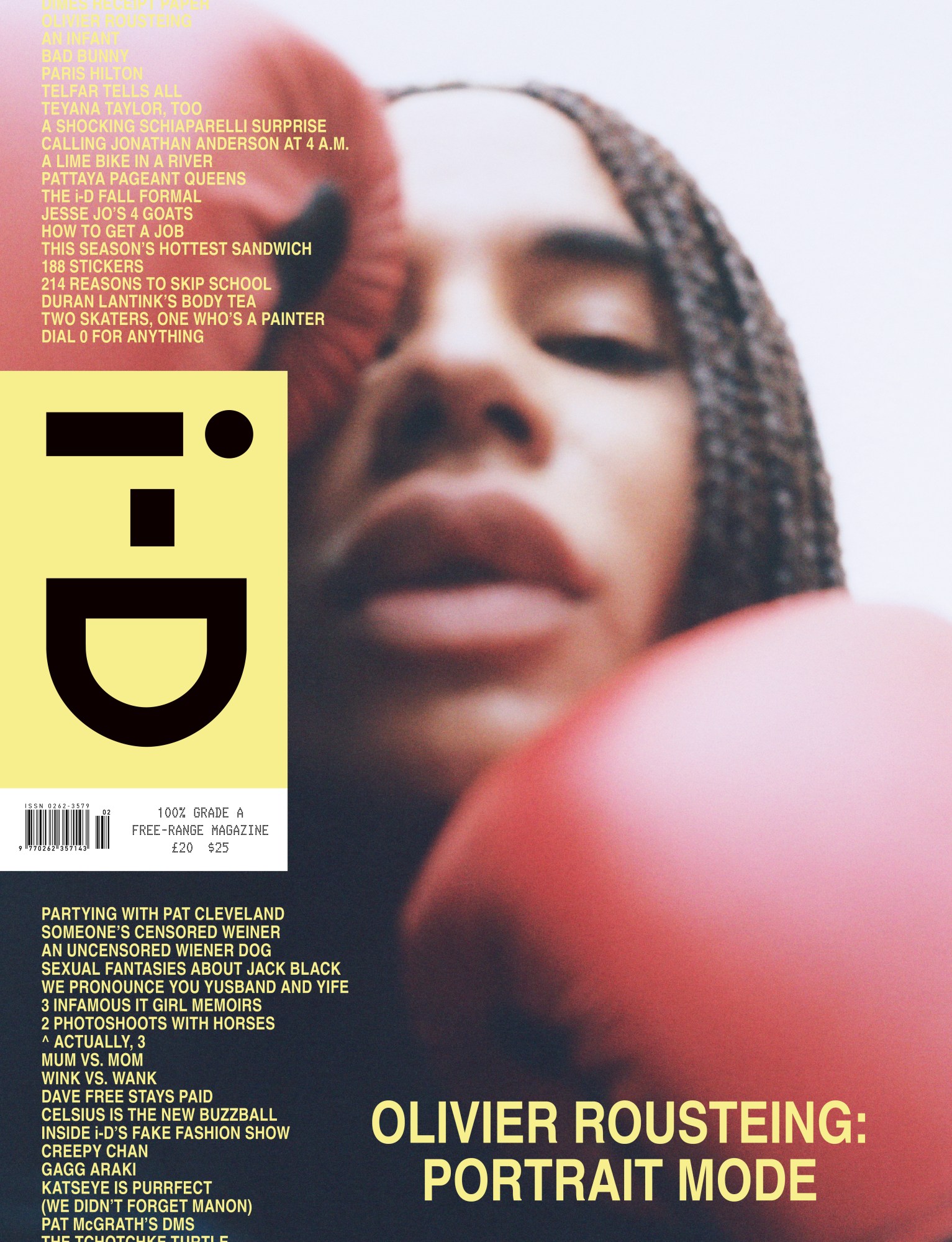

This story appears in i-D issue 375, on newsstands September 22. Get yours here.

photography FRANCESCO NAZARDO

written by ALEX KESSLER

“One word? Freedom.”

That’s how Olivier Rousteing answers the first question of the morning: How does it feel to be turning 40 this year? He arrives at the photo studio with the ease of someone who’s spent the last two decades under a spotlight, and learnt how to own it: grey sweatpants, black fluffy slides, and a white tee printed with his own face. “I call it ‘Instagram vs Reality,’” he says, pointing to his likeness on the shirt, then himself.

The 39-year-old is not just the creative director of Balmain, but a bona fide pop figure in his own right—the subject of a Netflix documentary, a near-decade-long front-row fixture, and a digital force with almost 10 million followers watching his every move. Long before fashion houses understood the power of social media, Rousteing was using it to author a new kind of creative leadership: personal, visible, and unabashedly self-aware. He didn’t just direct from behind the scenes—he became part of the brand’s visual language, a designer as influencer, as icon. In many ways, his rise predicted the era we’re living in now: one where fame and authorship, aesthetics and identity, are increasingly inseparable. There’s every reason to expect polish. Guardedness. A little distance. We laugh. I tell him I’m also a Virgo. He grins: “Triple Virgo. Sun, moon, rising. It’s a problem.” And from there, the conversation, and the walls, start to fall away.

Then Olivier does something extremely Olivier. He lifts a sculptural gold chain from around his neck and pops it open, casually revealing a tiny hidden flask. “One of mine,” he says with a smirk. “Whisky. Limited edition.” Of course it is. A necklace turned microflask of high-concept, high-price-point liquid luxury. The kind of thing only his beautifully eclectic mind would come up with. It’s part of his ongoing collaboration with Johnnie Walker Vault: first, a series of couture-detailed blends inspired by the seasons of his life and, next, a Couture Flask that marks his 40th birthday.

Rousteing has been the creative director of Balmain since his mid-20s, stepping into the role in 2011, succeeding Christophe Decarnin. At 39, he’s the longest-serving lead in contemporary fashion—surpassing the late Alber Elbaz’s celebrated 14-year tenure at Lanvin. “It’s scary when I think about it,” he admits with a half-chuckle. “Because when I started, I was the new kid,” he says, joining the French luxury house after five years at Roberto Cavalli, where he started as an intern and left as the head of womenswear. “Now I’m the last one standing,” he says, half amused, half reflective.

“Triple Virgo. Sun, moon, rising. It’s a problem.”

Olivier Rousteing

Balmain, under Rousteing’s tenure, has become a global symbol of amplified glamour—synonymous with jewel-encrusted, razzle-dazzle power dressing and a bold, body-conscious silhouette, worn by the likes of Beyoncé, Rihanna, and Kim Kardashian. His success has long since transcended the rarefied world of fashion, landing him on the cover of Forbes, designing costumes for the Opéra National de Paris, and collaborating with pop culture’s most influential names.

He remembers those early years as a blur of pressure and perfectionism. “I was the best student in the class,” he says. “Obsessed with the perfect heel, the most gorgeous hair, a seamless show.” Back then, he didn’t yet realise the difference between being a designer and a creative director. Now, he asserts confidently: “One is craft. The other is vision.”

When Rousteing shifted into the role of creative director, the universe of Balmain changed. “Creative direction means building a world,” he says. “And my world is about confidence, inclusion, and relevance in culture: music, social media, people who look like me.” What is now accepted, even expected, was overlooked or considered controversial in the 2010s: social media (Balmain was the first fashion brand to surpass a million followers on Instagram), musical collaborations (first with Rihanna and later with Beyoncé), and the representation of Black models and diverse body types. Rousteing heard again and again that none of it was “luxury.” He did it anyway. “People called me disruptive, but I wasn’t trying to be,” he says earnestly. “I was just following my instincts. It’s just that my instincts didn’t match their traditions.” He shrugs. “Eventually, I stopped caring. I realised if they’re going to say it anyway, I might as well earn it.”

Even now, when fashion has at least learnt the language of diversity (even if it’s still catching up on the practice), Rousteing carries a certain armour. It’s not defensive. It’s just self-forged. In 2020, he survived a horrific fireplace explosion that left his body covered in burns. “I was ashamed,” he says. “For a long time, I was hiding.” That moment of near-invisibility became a turning point. “You look in the mirror and see something you didn’t choose. Scars. Skin that doesn’t fit your own memory of yourself.”

“My scars are proof I’m still here. They’re not flaws. They’re the price of surviving.”

Olivier Rousteing

It was a brutal reckoning for someone so public-facing in an image-obsessed industry. But over time, he reframed the scars. “They’re proof I’m still here. They’re not flaws. They’re the price of surviving.” When he recently wore a sleeveless top to Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter Paris show—a small, defiant gesture—it was a moment of victory. “I asked everyone, ‘Can you see them? My scars.’ Everyone was like, ‘You look great.’ But it wasn’t about looking good. It was about not letting shame win.”

Rousteing embraces spirituality—not as a trend or wellness practice, but as a survival strategy. “I’ve always had to fight,” he says, “but now I’m trying to fight less. I’m trying to find peace, especially inside myself.” His journey inward hasn’t been linear. “I started doing sound baths recently and something happened. I saw myself during the explosion, the moment I got burned.” His voice slows. “In front of me was the version of myself before the accident, and I forgave him. I let him go. I cried. But I woke up feeling lighter. Like I’d finally made peace with that part of me.” He talks about energy now more than ambition. “I spent so long chasing perfection, because I was scared I wouldn’t be enough. But now I just want to know myself better. It’s not about success anymore. It’s about soul.”

He’s spent much of his life, publicly and privately, searching for origins. In Wonder Boy, the 2019 documentary that followed his rise and inner life, the Bordeaux-born designer opened the door to his most personal story yet: the search for his birth mother, who put him up for adoption when she was just a teenager. The journey led him to uncover difficult truths. They were destabilising. After filming one of the most emotional scenes, he returned home and threw up. “It wasn’t catharsis. People think once you get answers, you feel better. But that’s not how humanity works. I got answers, and I felt sick,” he tells me. One of the last things his biological mother had written, he recalls, was simply: “I just want to go back to my real life. This is a nightmare.” That line haunted him. A mother who was still a child, and a son born into shame that wasn’t his. He pauses. “That’s when I realised: the mask I was wearing wasn’t just about fashion. It was my protection.”

That search for self is closely linked to his idea of family, both the one he was adopted into and the one he’s built. “I come from an orphanage, so I believe in ‘chosen family.’ The people you work with, the ones who stay, the ones who see you when you’re not performing. That’s family.” His adoptive parents, a white French couple, raised him with love, and he’s deeply grateful. “But I always wanted more. More people. More connection. That’s probably why I built so many families around me—in fashion, in music. I need people around me who remind me that I’m real.” He smiles, a little shyly. “Maybe that’s what legacy is, too. Not just what you make, but who you make it with.”

It’s a sentiment that shows up not just in the people around him, but in the projects that bear his name. His creative universe keeps growing. In early 2025, he launched a collaboration with Johnnie Walker Vault. Not a brand deal, he’s quick to clarify, but a creative exercise rooted in memory. “We talk a lot about luxury,” he says, “but what’s more luxurious than memory? Than permanence? Something that lasts.”

“It’s not the clothes. It’s the kids who see me, a Black kid from an orphanage, and think, ‘If he made it, maybe I can too.’”

Olivier Rousteing

His 40th birthday, unlike his 30th (a lavish celebration in Los Angeles that surprised even him with a guest list including Jennifer Lopez, Kim Kardashian, Justin Timberlake, and Cara Delevingne) will be cosier, he says. “Maybe LA again,” he muses. “A few people who’ve mattered most. Some old-school music. And watching the sunrise.”

He’s not anti-glamour (far from it), but he’s growing more attached to the idea of classicism—things that endure. “I used to think you had to be everything, all the time. Now I just want to be real. That’s harder.” When I ask him what legacy means to him now, he doesn’t hesitate. “It’s not the clothes,” he confidently states. “It’s the kids who see me, a Black kid from an orphanage, and think, ‘If he made it, maybe I can too.’” It’s not the first time he’s said it. But maybe it’s the first time he’s fully felt it.

There’s a certain tension in Rousteing’s longevity at Balmain—a house once rooted in a particular kind of French conservatism, now unmistakably global, unapologetically loud, and unafraid of emotion. He made space for hip-hop and heritage to share a stage. He made his own face part of the brand’s vocabulary. He didn’t just modernise the house––he radicalised its tone. “It’s not about chasing relevance,” he says. “It’s about designing a world people want to live in. Even if just for a few minutes.”

The studio we’re in is quietly loaded––couture draped beside boxing gloves, whisky beside water, legacy beside self-revision. Everything feels like a metaphor for a man straddling multiple worlds. Everything is considered. Nothing is performative. When I ask what’s next, he doesn’t give a media-trained response. Just a pause. “I don’t know. That’s the exciting part. I’ve spent so long trying to be the right choice for brands, for people, for my own history. I think now I just want to be the choice I make for myself.”

As we say goodbye, he hugs me earnestly. No cameras, no spectators, just Olivier feeling authentically unmasked. Maybe that’s what the “freedom” of turning 40 really is. Not a reinvention, but a move towards something softer and all-embracing. Settling into a version of yourself that feels irrevocably, fearlessly you.

set design CHLOE BARRIERE AT SWAN MGMT

photography assistants MARTA PABA & HUGO PALAYER

styling assistant MAGDA ATIGELI

production THE MORRISON GROUP

production manager OLIVIA GHALIOUNGUI

production assistant MAIAN TRAN

post production OFFICINAOTTO

location STUDIO ROUCHON