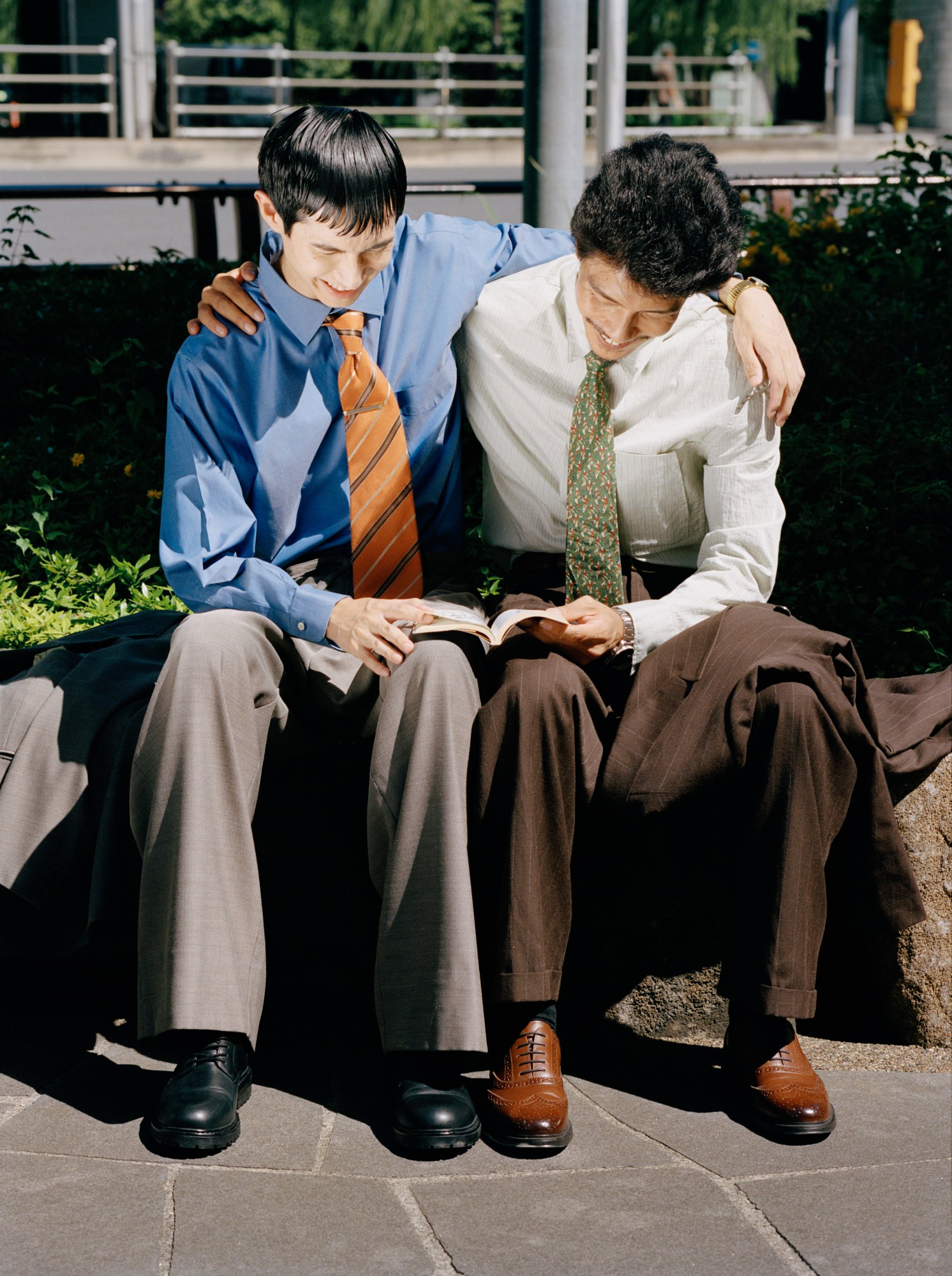

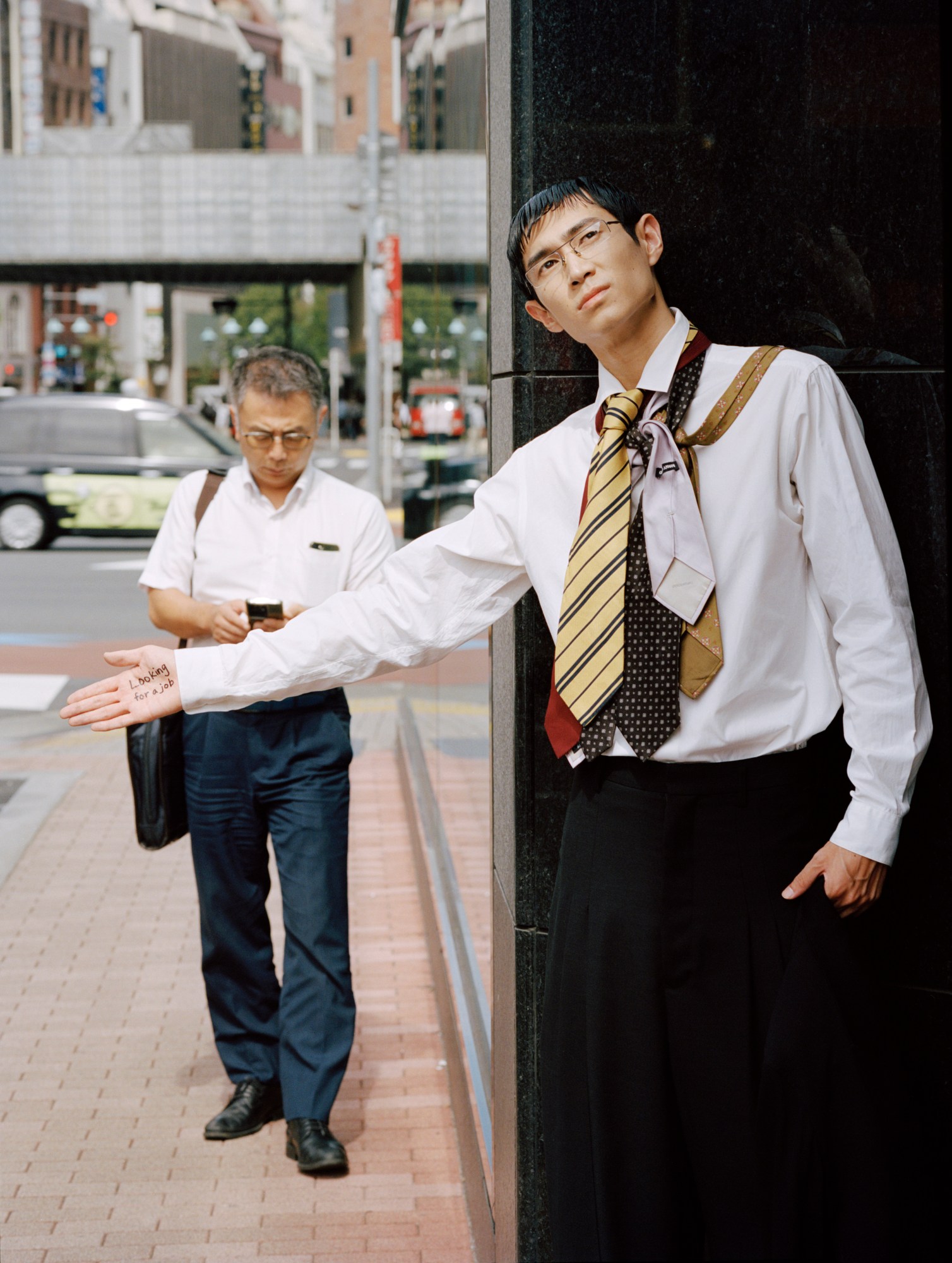

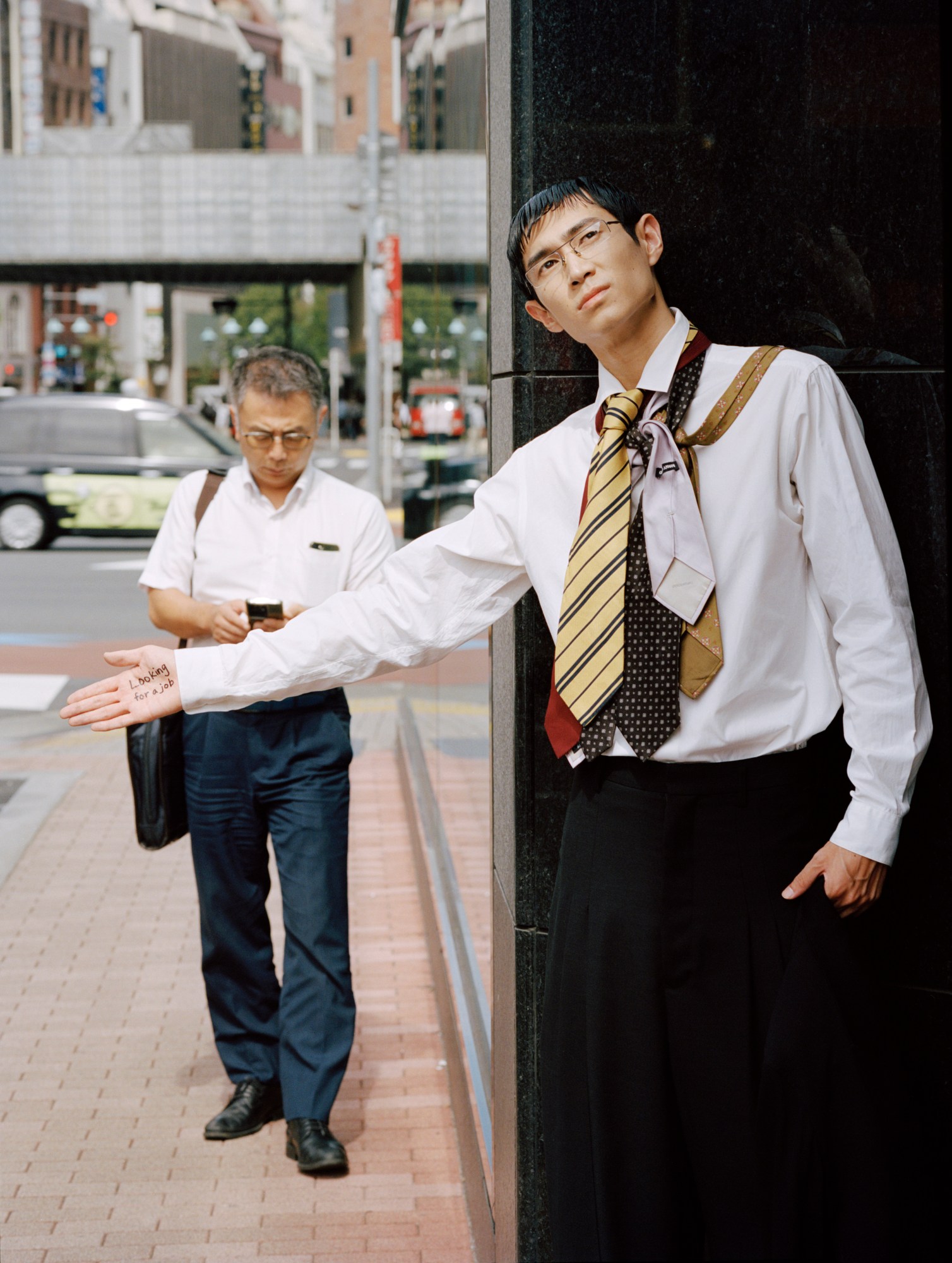

creative director & stylist REINA OGAWA CLARKE

photography XIAOPENG YUAN

Soshi Otsuki wants to be the very best, like no one ever was.

Earlier this month, the 35-year-old menswear designer based in Tokyo was announced as the winner of the LVMH Prize for his brand SOSHIOTSUKI. His beautifully draped tailoring, which explores Japan’s relationship with Western clothing, resonated with a judging panel that included Jonathan Anderson, Phoebe Philo, Sarah Burton, and Nigo. Addressing the judges, he was direct: “SOSHIOTSUKI’s mission is to define a new Japanese clothing tradition to replace the kimono.”

Otsuki was always gunning for the win. First shortlisted for the prize back in 2016, when he was only two collections in, this time he came back with mettle, gumption, and some excellent tailoring. Evoking the bubble era of 1980s Japan, when cash-flush salarymen shelled out for Armani suits they saw as the height of sophistication, Otsuki’s take is soaked in nostalgia but also feels right for the moment (more on that later).

As well as the main prize, the Karl Lagerfeld Prize and the Savoir-Faire Prize were also up for grabs, going to Steve O. Smith and Torishéju, respectively. “I expected I would win at least one of them, but when they announced the winners of the other two, I thought it was over,” he says. He barely remembers his own name being called. He was thrilled, but the weight of what it meant sank in quickly. “When I saw other designers winning these awards in the past, I felt like it must be really satisfying,” he says. “But when you actually win one yourself, you feel the responsibility get heavier, for what you’ll do next.” It’s tough at the top!

The €400,000 prize money, he says, won’t be prematurely blown on a big Paris runway show—though a presentation could be on the cards in the next few seasons. Mostly it will go toward hiring staff (he has never even had an intern) and, since he currently works out of his house, a proper studio. “I have to pay thirty percent tax on it to the Japanese government too,” he sighs.

Otsuki, with his crop of black hair and impassive expression, is a stoic character. He speaks little English and mostly does interviews over email—he’s a big fan of ChatGPT—but I meet him on a hot September morning at his PR’s office in Harajuku. In Paris in the run-up to the prize, he struggled to join in designer conversations. “I felt like there was a barrier at dinner where I couldn’t really connect with the other designers, and it was a bit tough because I couldn’t speak at all,” he says. Now that he expects to spend more time in Europe, he plans to start English conversation classes.

He wears a uniform of blue shirts and dark pants—today, a blue vintage Hermès double button-up and a pair of black trousers he recently bought from Dries Van Noten in Paris. He reveres Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto, as nearly all designers do (“I wouldn’t want to give a presentation to them, I’d be too scared”), and among contemporary designers he rates the off-kilter knitwear brand Pillings by his friend Ryota Murakami (“What he does is just so honest and pure”). In his downtime, he plays with his dog Fune, a five-year-old Shiba Inu. And when he’s not fighting his way to the top of the fashion industry, he’s battling other players in the Pokémon trading card game on his phone during cigarette breaks. (I peek at his score… He’s competitive.)

When fame and success come, so do haters. Alongside the flood of congratulations came comments that Otsuki was just imitating Armani, too mired in nostalgia, or didn’t deserve the prize. “I think some people tend to get the wrong idea [about my clothes],” he explains. “They are about an inferiority complex that Japanese people have about fashion.” Back in the 1980s, when wallets were fat and lapels fatter, salarymen decked themselves out in European suits, and “Made in Italy” became a status symbol that signaled taste and money. Those power-dressed guys zipping around the streets of Shimbashi looked glamorous, like something from a Takeshi Kitano movie, but Otsuki also sensed unease in the admiration for a foreign culture at the expense of one’s own. “Rather than blindly believing that ‘Made in Italy’ is the best, I think that looking at it from a bird’s-eye view is cool,” he says. “It’s not a straightforward perspective—it’s a bit twisted.”

To view Otsuki’s work as a straightforward Armani homage or nostalgia-fest is to miss the cultural iceberg beneath its surface. Instead, his clothing plays with complicated feelings of identity and ego, channeling them into suits for the moment while flipping “Made in Italy” into “Made in Japan.” He repurposes deadstock kimono silks into white shirts, finds forgotten wools at old Japanese factories to craft into suits, and adds traditional kimono pockets into power-shouldered blazers. Accessories include juzu prayer beads made into bracelets, and silver and gold rings and belts that function as cigarette holders. The resulting look is part chain-smoking Yakuza playboy, part dandy, with an ironic dollop of salaryman swagger. “It’s a bit of a paradox, but everything connects back to Japanese tradition,” he says. “I don’t know if I’ve overcome that complex myself or not.”

What does he see for the future of his brand? His name above the door on stores from Omotesando to the Champs-Élysées? “I’d like to have my own factory,” he says. “Nothing grand. I imagine it as having sewing machines and seamstresses.”

His biggest ambition, however, lies in not just making good clothes, but shifting fashion culture. “The office suits that people wear in Japan are too standardized and I think look pretty boring. So [my suits] are like an image of something else. I want them to become a core, a starting point, that other things can follow,” he says. “I want my suits to be in the history textbooks.” He doesn’t blink.

creative director & stylist REINA OGAWA CLARKE

photography XIAOPENG YUAN

director & dp NOBU ARAKAWA

hair TOMIKONO

makeup DASH

casting KOSUKE KUROYANAGI (VOLO)

model RYO ITO (NUMBER EIGHT)

model JUMPEI OKAZAKI (NUMBER EIGHT)

pr ENA KAJIYA (MATT)

production KAORI OYAMA