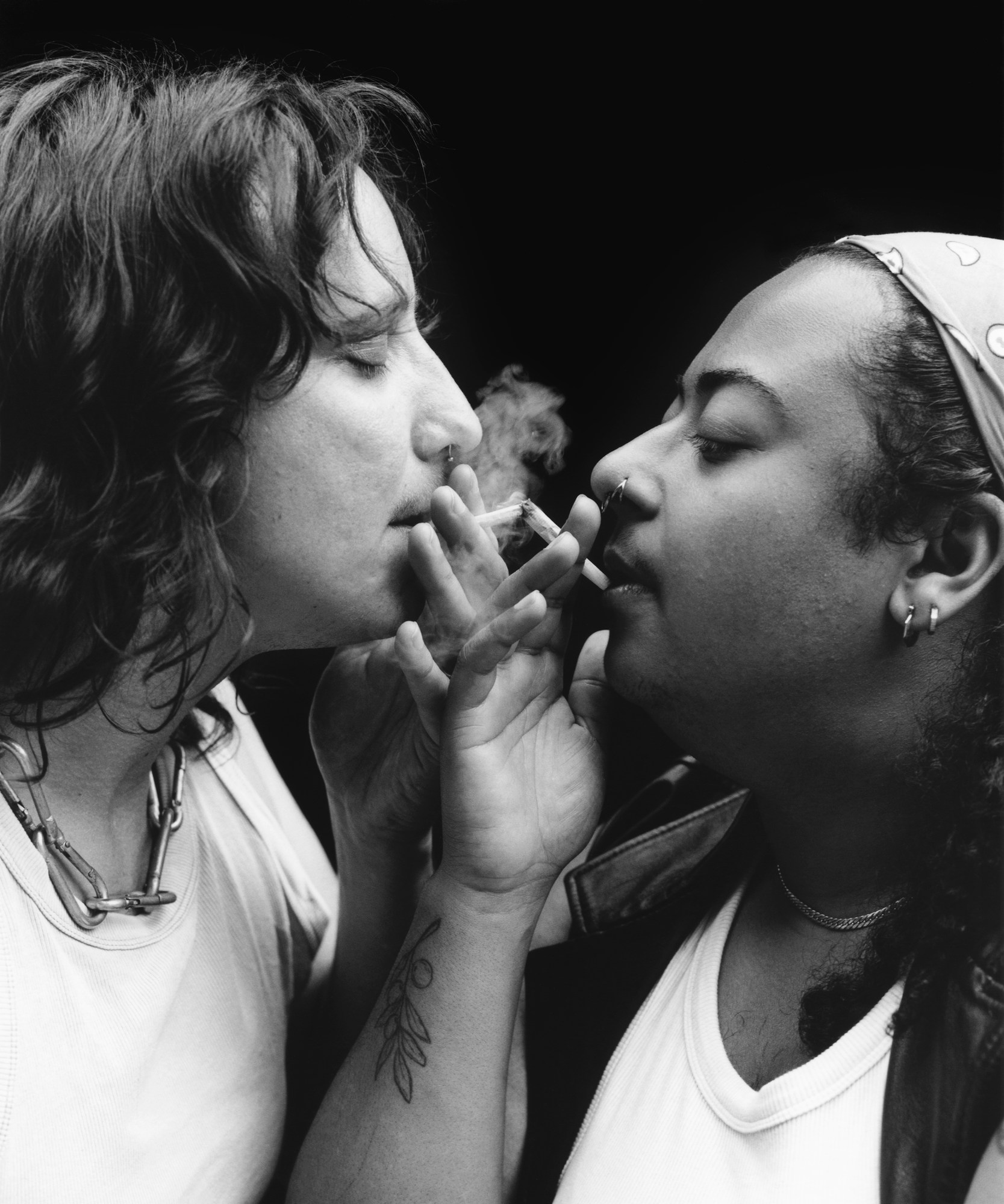

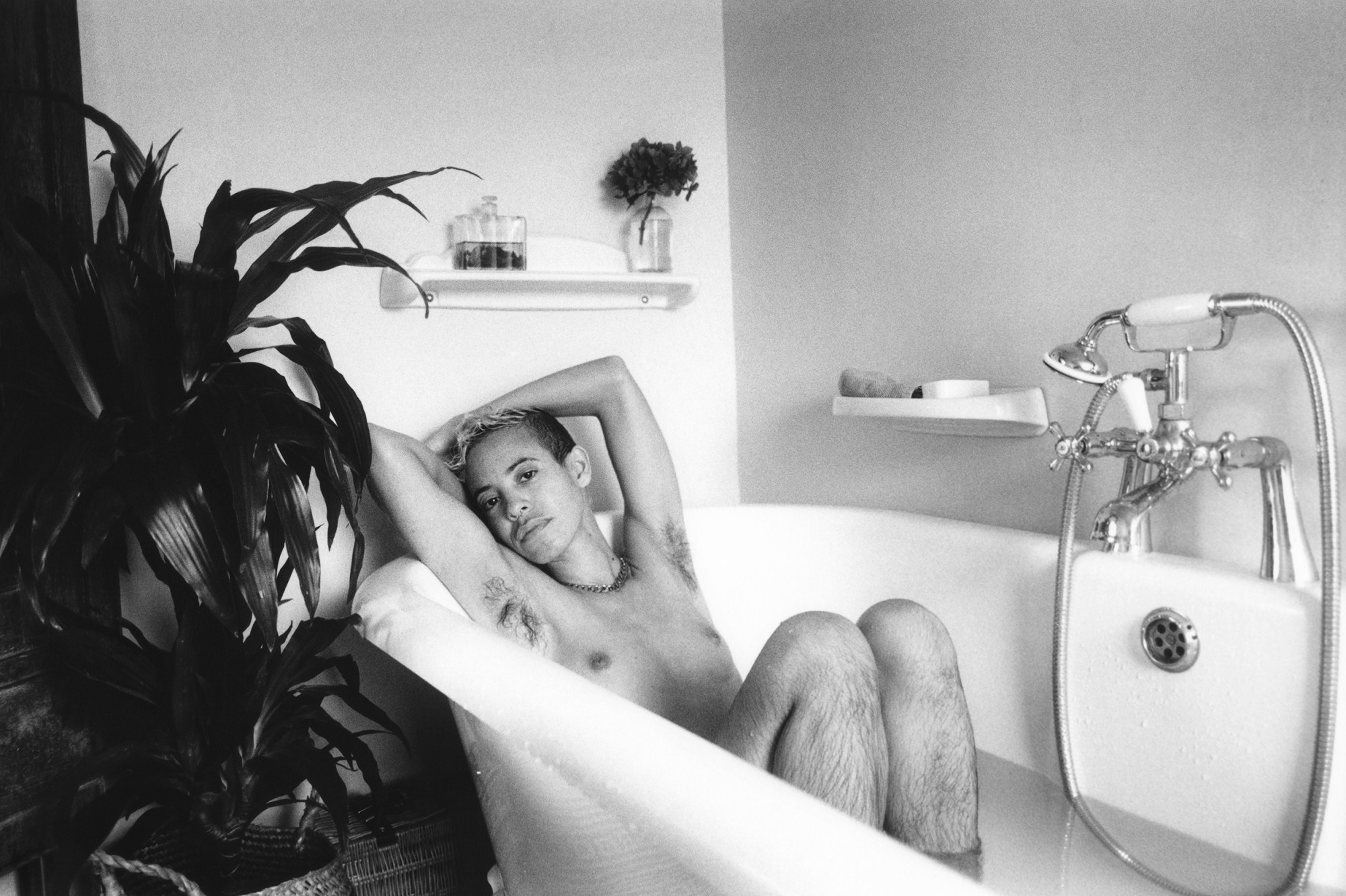

Producing photobooks can be timely, laborious and, most of all, expensive. But they remain crucial artefacts — shaping stories, preserving voices and offering rare insight into lives too often left off the page. That’s why Orion Isaacs and El Hardwick are raising funds to bring their new photobook t-fags to life. t-fags focuses on the experiences of trans men, transmasc and non-binary folk. Made up of photographs and interviews, the project began almost three years ago, when El and Orion noticed a distinct absence on the shelves of queer bookshops. t-fags brings together images and voices in a collaborative exploration of trans intimacy, desire and identity, mapping the many ways trans people see and desire themselves.

You can help support the project by donating to the Kickstarter here.

Jackson Bowley: What do you do?

Orion Isaacs: I’m a writer-director. I also work across installation and visual art. I’m the creative director and interviewer on the t-fags project.

El Hardwick: I’m a photographer, and I’ve been taking photos for most of my life. I’m also a musician and occasional curator of events and exhibitions.

What was the catalyst for this project?

EH: Whenever we would go to LGBTQ+ bookshops in London, we would naturally be drawn to the shelves with the art books. Often this would only be a small section of the shop, and the photography books that we did find were predominantly full of beautifully shot ’80s and ’90s homoerotic photographs. Artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, Mel Roberts, Tom Bianchi and Hal Fischer. But we were left wishing (as you so often do when you are trans) that there were trans guys, non-binary fags and folks of different body types included in them.There are lots of amazing trans photographers, but in terms of the specific intersection of homoeroticism and transness, the closest existing book that we have found is Del La Grace Volcano’s The Drag King Book from 1999 (long out of print), but that is only adjacent to what we are doing since it is about drag kings rather than specifically transness or faggotry. Ajamu X has also beautifully explored black gay identity in his photography for decades – and more recently he exhibited a new portrait series of black trans men, which we were thrilled to see displayed at Autograph Gallery in London.

OI: We were also looking at a lot of classic gay cinema and wanted to see these archetypes reimagined with trans masc, trans men and nonbinary t-boys as the heroes. Homo archetypes like River Phoenix & Keanu Reeves in My Own Private Idaho, and Daniel Day-Lewis & Gordon Warneck in My Beautiful Laundrette. There’s a well-trodden path of lush independent homo cinema, which holds a sensibility we wanted to tap into through photography. We were thinking about locker rooms, cruising in alleyways and at lakes, sailors, motorbikes, wrestling, jock straps, swimming pools… We had this idea to make a series where it’s about getting in touch with the participant’s fantasy or their specific expression of fagginess, and then materialising this through an image.

How has this project evolved over the three years since you began. Have there been any unexpected surprises?

EH: The earliest iteration of the project was an editorial we shot for C☆NDY TRANSVERSAL Magazine in 2022, sponsored by Acne Studios. However, we wanted to explore the idea more in-depth, where the participants could wear their own clothes (or at times, fewer clothes)! We put in a pitch to exhibit an audio visual installation at Rosa Kwir’s gallery and trans masculine archive in Malta (for their Tender & Masculine group exhibition), which included portraits and audio interviews with a handful of participants. We knew after that, we wanted to continue building upon this body of work. We also wanted the portraits we took next to feel more cinematic, and to delve even deeper into classic fantasies, iconography and characters found in gay art. So we put out an open call for participants, and those who took part were sent a moodboard. We asked them what themes and locations they were drawn to. So it became even more sexy, and even more collaborative, the more the project developed.

OI: The photos have definitely become increasingly like film stills rather than straight up portraits. We’ve been leaning way harder into creating cinematic, storied moments.

If you could describe the book’s mood in three words, what would they be?

OI: Sensual, Tender, Hot.

EH: Sexy subversive fantasies!

Could you describe the process of how you went about shooting and interviewing each subject?

OI: After participants chose the specific area of the moodboard they were drawn to, we’d seek out location ideas and have a back and forth about what clothes they would like to wear, telling them to bring along a couple of their faggiest outfits. We always start by sitting together and chatting, mostly about what’s going on in the participant’s life right now, the week so far, mood, landing together… We also chat about comfort levels, any triggers we should be aware of. There’s a tender, exploratory energy that leads to intuitively finding an image that feels spontaneous and comfortable. We don’t linger on one image for too long, moving briskly and trying lots of different ideas.

EH: I think the process of collaborating together on this project has really made me be much more intentional around how consent works on set. I’m not saying my shoots were uniconsensual in the past—but so often in the photographic industry, and especially in the fashion industry, the subjects of photographs have little space to talk about triggers, it’s a norm for stylists to adjust hair and clothes without asking models if they are ok with it, and subjects have no say in which images the photographer publishes. We want folks to love the photographs of themselves. I’ve been taking photos and sharing my work online since I was twelve years old, and as I’ve gotten older I question the ethics of photography more and more. There was something about working with Orion, not just because they’re my romantic partner, or that they are a hugely talented artist – but they have a real sensitivity to how they interact with everyone they meet. It has really made me fall in love with photography in an even deeper way, that I maybe lost for a bit. I feel like a better photographer for it.

What does the word ‘fag’ mean to you both?

OI: My understanding of fagginess shifts in ways that remind me not to pin the word down as one thing. Sometimes ‘fag’ is thrown like a weapon from the outside. Other times, it’s a force of sensuality and playfulness found from within. And then, it can be all mixed up; alive and changing, but forever flirting with expectations around masculinity. All these historic slurs: “he-she”, “dyke”, “fairy”, “fag”… they’re all words that unhappy people came up with to attack any signs of gender expansiveness, in an attempt to dim the gorgeous bright lights of queers, overflowing with who they undeniably are. We take it all back – Our words! Our light!

EH: The initial editorial we did for C☆NDY TRANSVERSAL was all focussed on couples and throuples who identified as fags. So initially faggotry, in terms of this project, was about dynamics. I had also just read the then-recently published diaries of Lou Sullivan (who is often regarded as the first openly-gay trans man to transition in the public eye). His writing really opened my eyes to seeing myself as a fag (even though Lou was a trans man and I identify as non-binary). But as both the project and I have evolved, it feels more like a word that allows me to invite back in some of the femininity I initially rejected when I came out as trans, for fear that I’d be misgendered. There is a clear distinction in my experiences of being assigned female at birth, and now identifying as a fag. They’re absolutely not the same. I’ve started wearing skirts again and braiding my rattails – but the skirts and hair aren’t the same as they were pre-transition. That feels pretty faggy to me.

Did any of the subjects’ interpretations of the word ‘fag’ challenge or expand your own understanding of it?

OI: I have a pretty broad and flexible understanding of the word so my interpretation didn’t feel challenged as such. The expansiveness of the conversations felt exciting to me. the word ‘fag’. No two people had exactly the same experience. I was very moved by participants who were coming to the project to explore what this word meant to them for the first time, so the actual process of taking the photos was a way of getting in touch with something out of curiosity and playfulness. How cool that a photo shoot could be a doorway to an unexplored part of yourself!

EH: Although the genesis of the project was looking at homoerotic photography, participants in the project have cited so many reasons for identifying as fags. For some, it is about sexuality, and an identification with gay male spaces, subcultures and cruising. A lot of people who took part have had the word fag thrown at them in a derogatory way by strangers, and to reclaim it is both empowering and affirming – in much the same way that cis gay men have also reclaimed it. For others, being a fag is synonymous with being gender nonconforming. It is the closest word for describing themselves, that doesn’t fit neatly within the gender binary.

Why is physical print important to you both?

EH: It makes a lot of sense, considering that the origin of the project began with us looking for this nonexistent book in bookshops, and deciding that we needed to create it ourselves. We really want this book to equally appeal to LGBTQ+ people who might not normally buy photo books, and also to be a beautiful art object that could easily sit alongside coffee table books by iconic, respected photographers. It also feels increasingly important to have work presented offline – I feel like social media is failing at helping artists promote our work, and the work was never even created to be viewed on a small screen. Everything was shot on film, and handprinted by the wonderful Sarah England (who is such a talent, and runs her own darkroom in London). I adore how that process really slows down the craft, and honestly the work looks its best when it is printed.

Did you have any plans for the launch?

EH: Provided we reach our Kickstarter goal, we have a date pencilled at Photo Book Cafe in Shoreditch, which is one of our favourite spots in London. Put 6-9pm Tuesday 24th February in your diary if you would like to join!

You can help support the project by donating to the Kickstarter here.