It’s a sunny Saturday in New York, the kind of day that wakes you with a smile on your face and burning need to be outside. It’s warm enough for shorts but cold enough that I won’t break a sweat while I walk—the perfect weather. I’m making my way to the Lower East Side to Hannah Traore Gallery riddled with nerves and excitement. My belief in the power of discomfort propels me towards Misha Japanwala’s newest gallery show, Sarsabzi, her explorations of the human form boldly rejecting notions of imperfection and shame placed upon marginalized bodies.

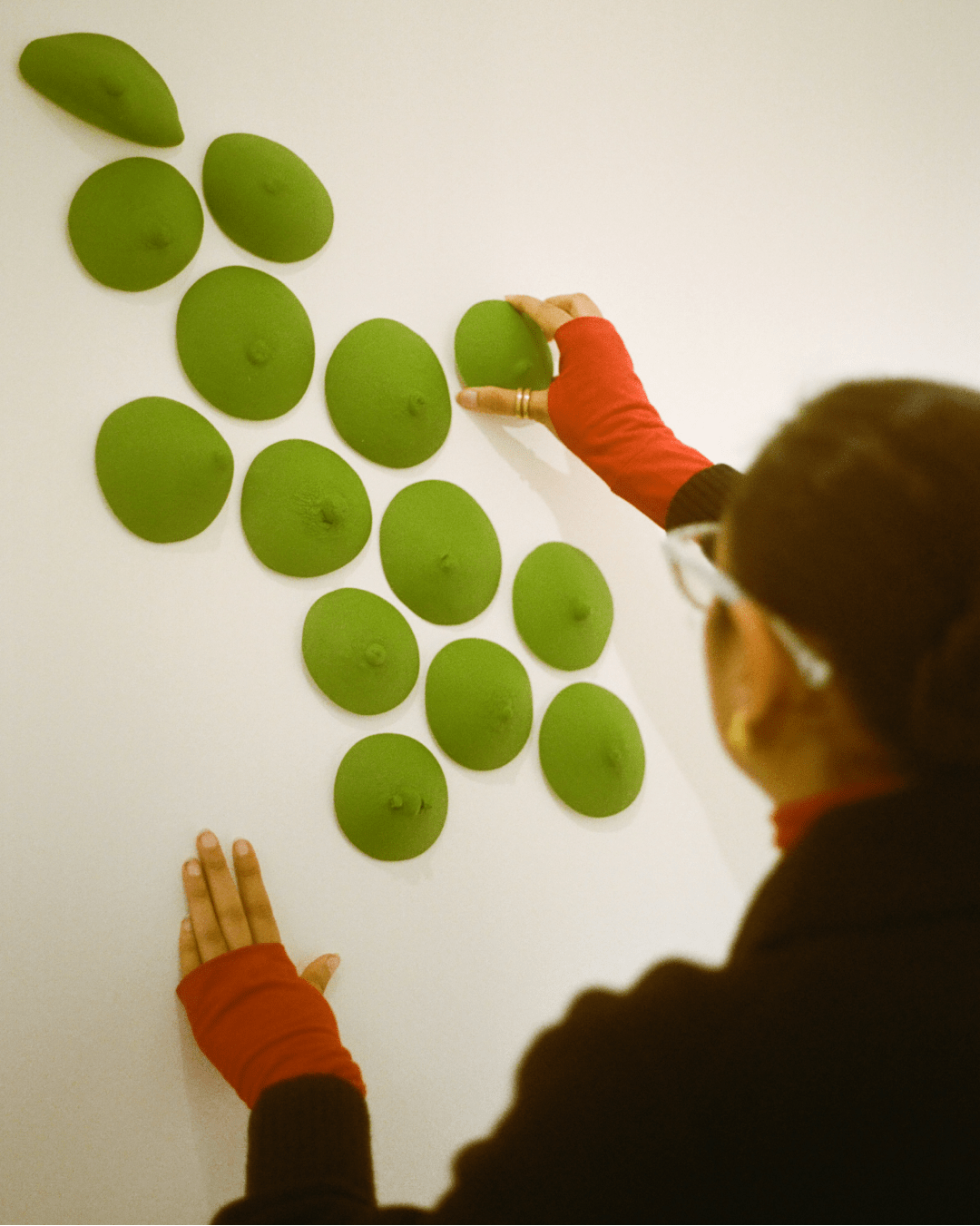

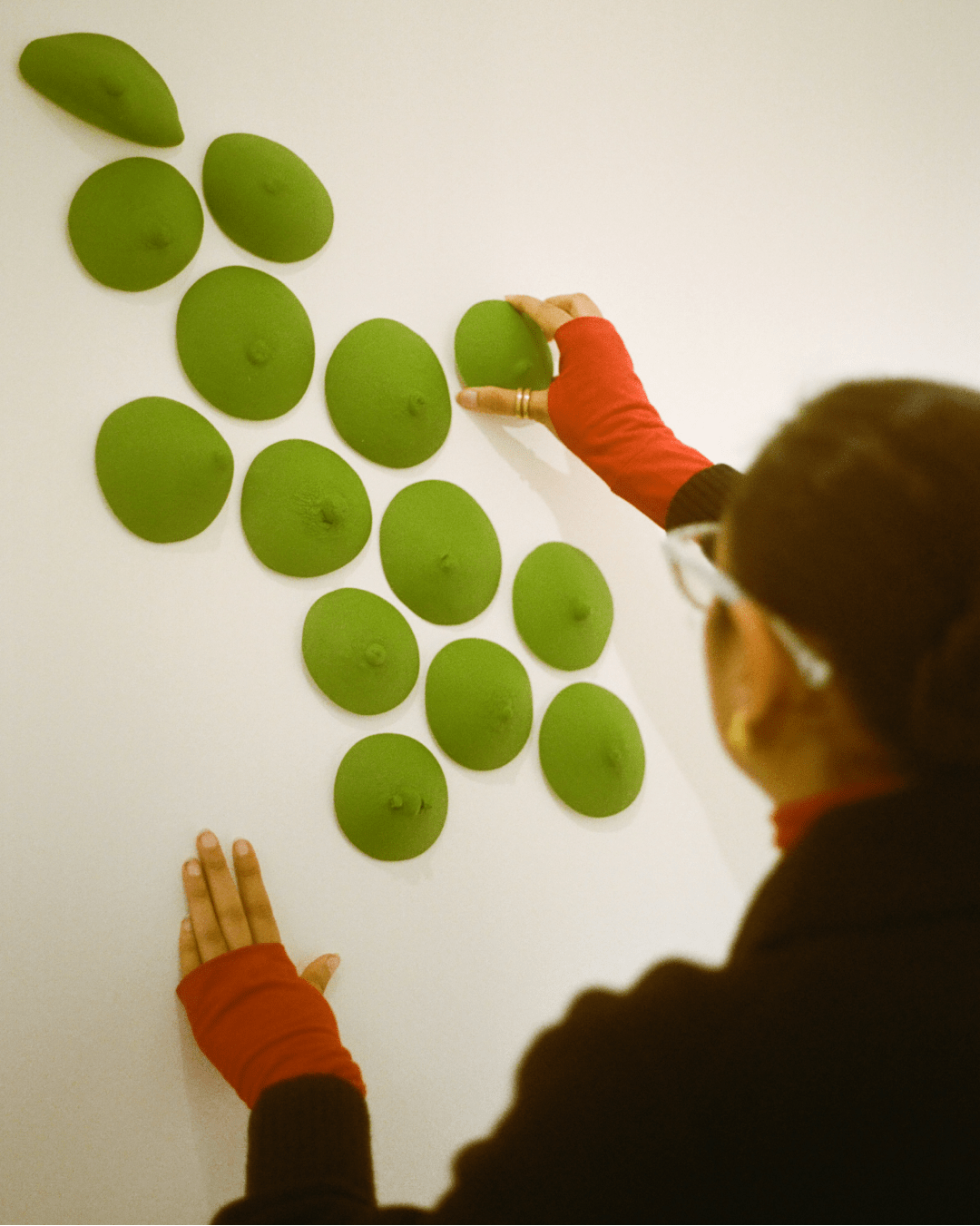

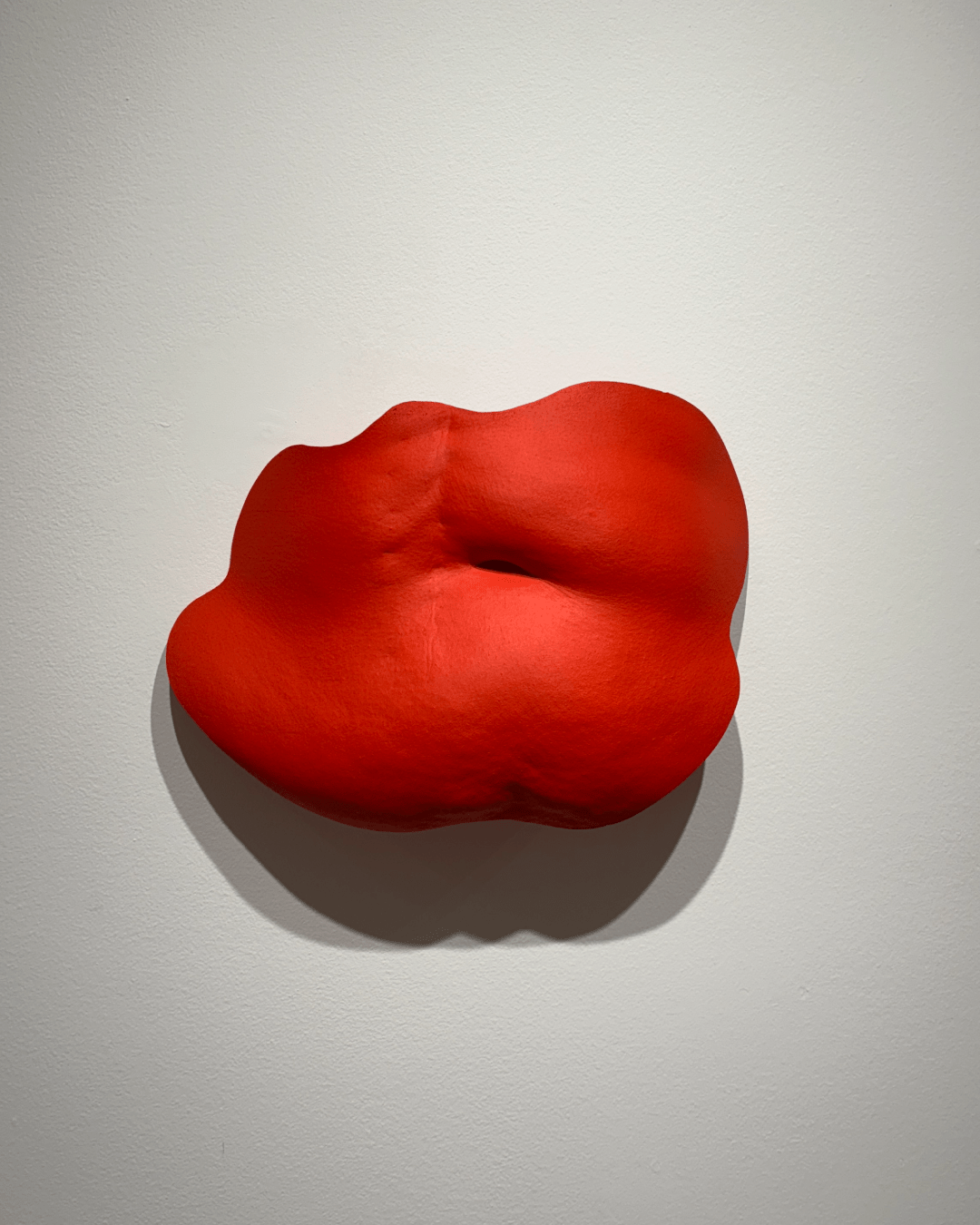

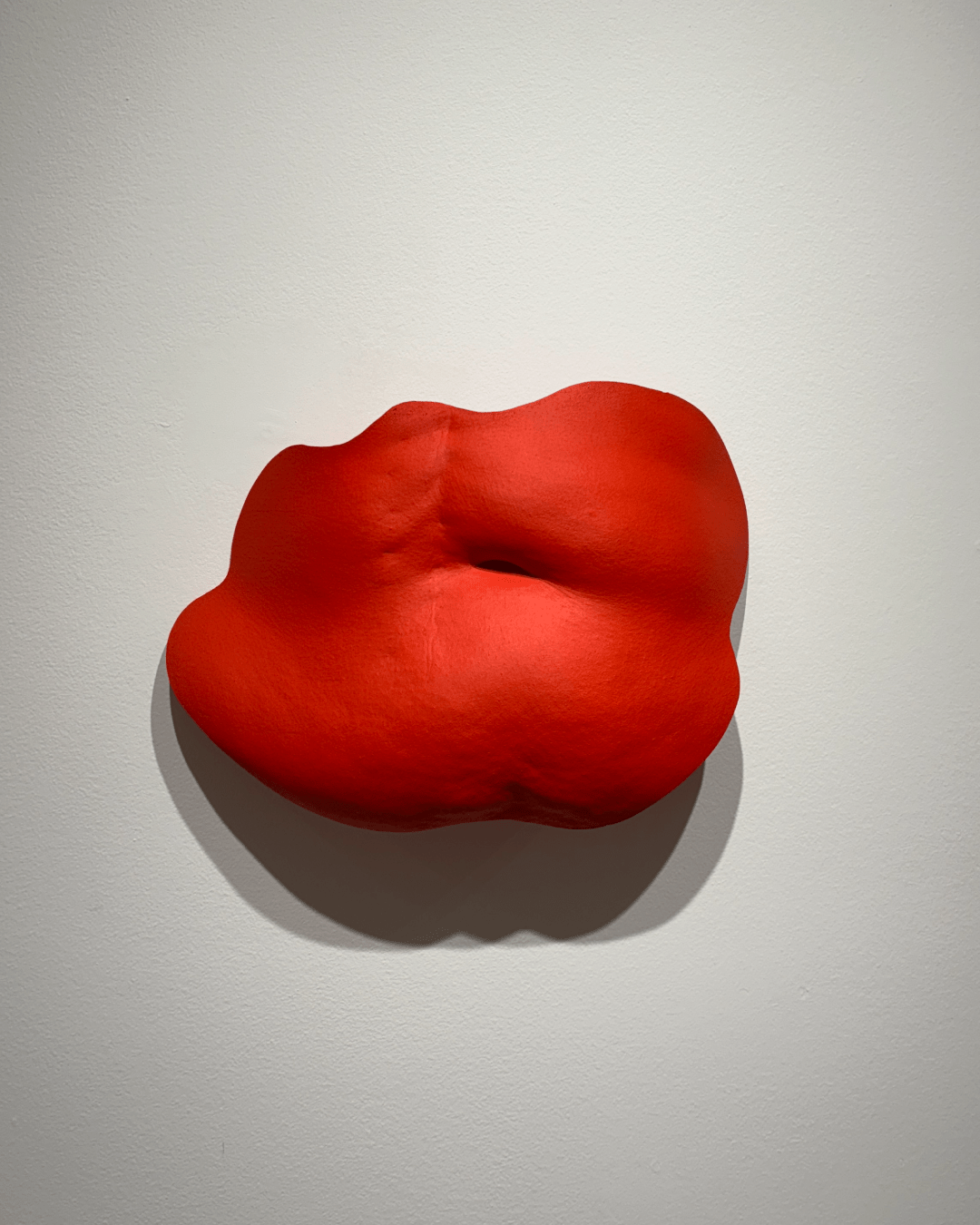

The show is an expansion of her Topographies series, where she uses silicone to create vibrant sculptural moldings of femme and nonbinary bodies, liberating their forms and imperfections. The works that line the gallery walls are moldings procured from a series of open calls and will soon be joined by a wall of nipple casts. Japanwala is holding ongoing molding sessions open to the public to line the gallery walls with nipples to honor Zahra Khan, who sat with Japanwala the day before a double mastectomy in response to Japanwala’s first open call, which is where I am now headed: to get my nipple cast.

The night before, as I’m going through the motions of my deeply regimented nightly rituals, I have the urge to groom accordingly. The looming thought that I will soon be displaying my body and preserving its form makes me want to do all that I can to reach a feeling of perfection. I wonder what one does to prepare to get a cast of their nipple made. In what form do I want to be remembered? It then dawns on me that this is the very antithesis of what is bringing me to the gallery in the first place. My mission is not to embrace my body in its most perfect form, but rather, to honor whatever state it shows up in.

As I open the gallery doors, I’m gearing up to reject the very ideas I’ve internalized since the day the internet told my 10-year-old self what a thigh gap was and why I needed one. In the white-walled open space I’m struck by the vibrant colors of the work around me, all silicone moldings of bodies that Japanwala has transformed into striking sculptural forms. When I meet her in the lower-level room of the gallery, the warmth of her presence begins to ease the tension in my body. My nervous system is soothed by the comfort in the air and the row of nipple casts I see on the floor next to me. The fear I’m feeling as we prepare together is one I share with the people who have sat with her before me, a fear Japanwala has become an expert at facing.

Throughout Japanwala’s process for Sarsabzi, she tells me she was fixated on one word: blemish. The Oxford Dictionary defines blemish as “a small mark or flaw which spoils the appearance of something.” When Japanwala learned the definition of the word that lives in so many of our vocabularies, she was struck by the cruelty of the language used regularly to describe marks of life on our own bodies. Her practice encourages us to approach these marks with care and respect, rather than shame or distaste.

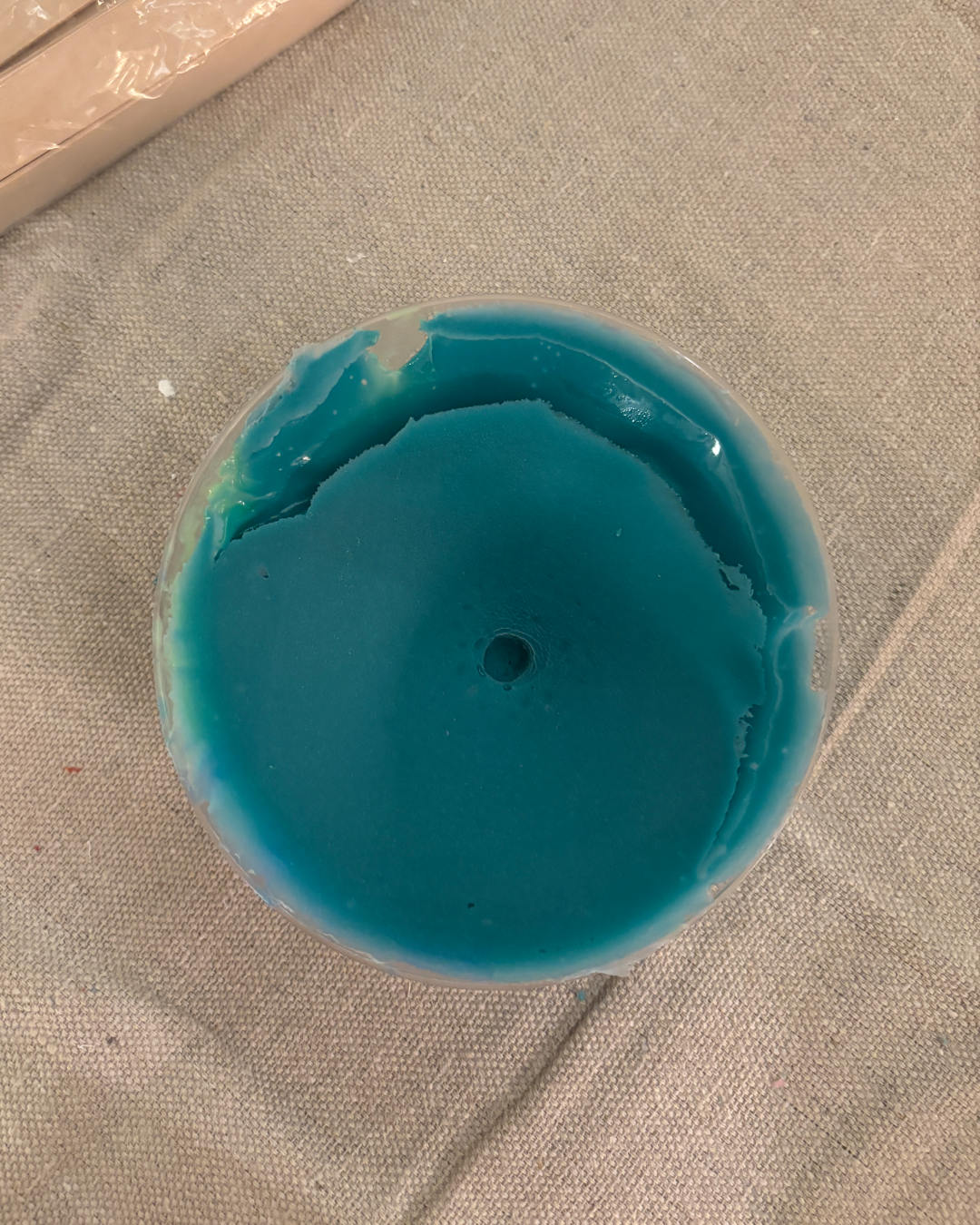

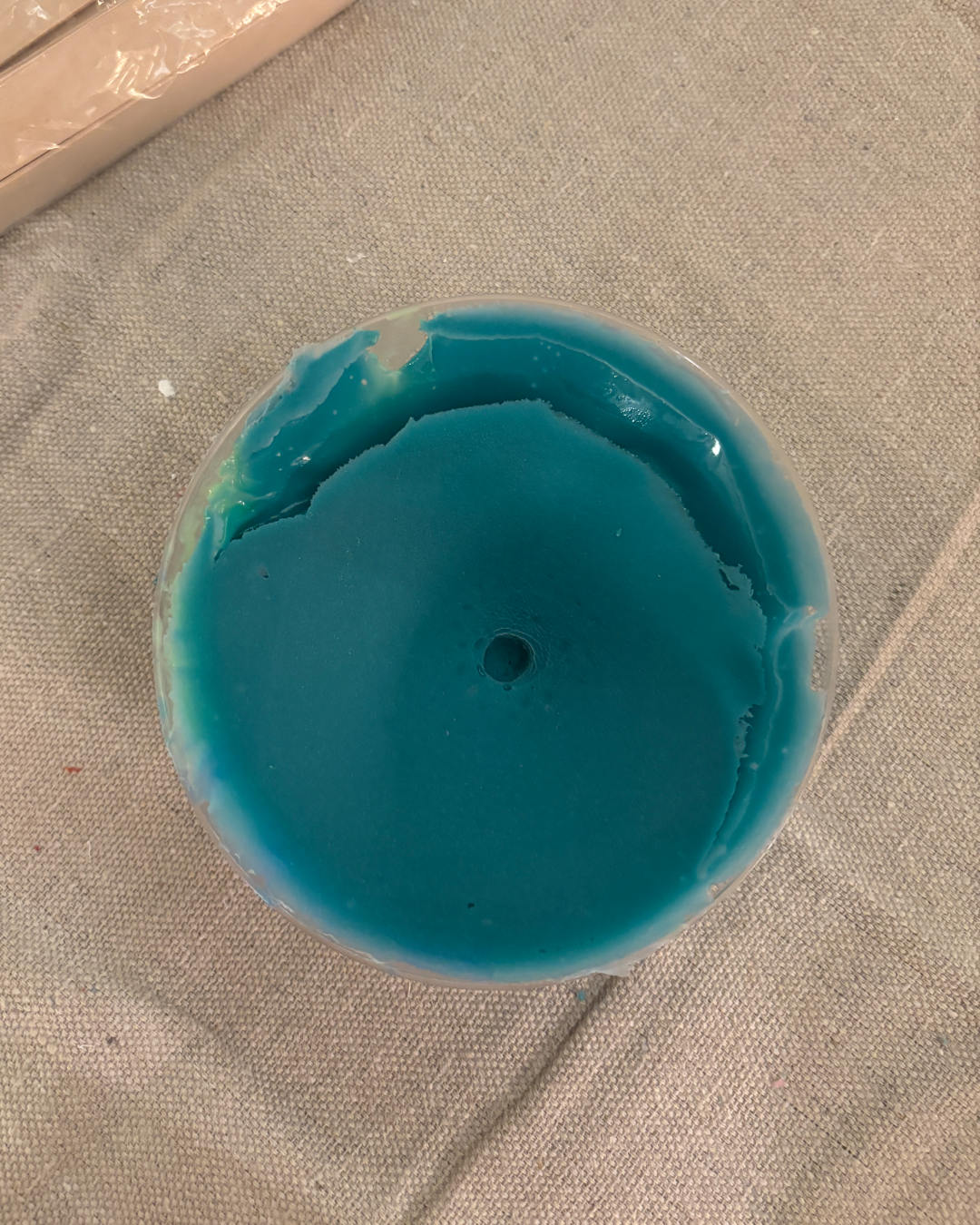

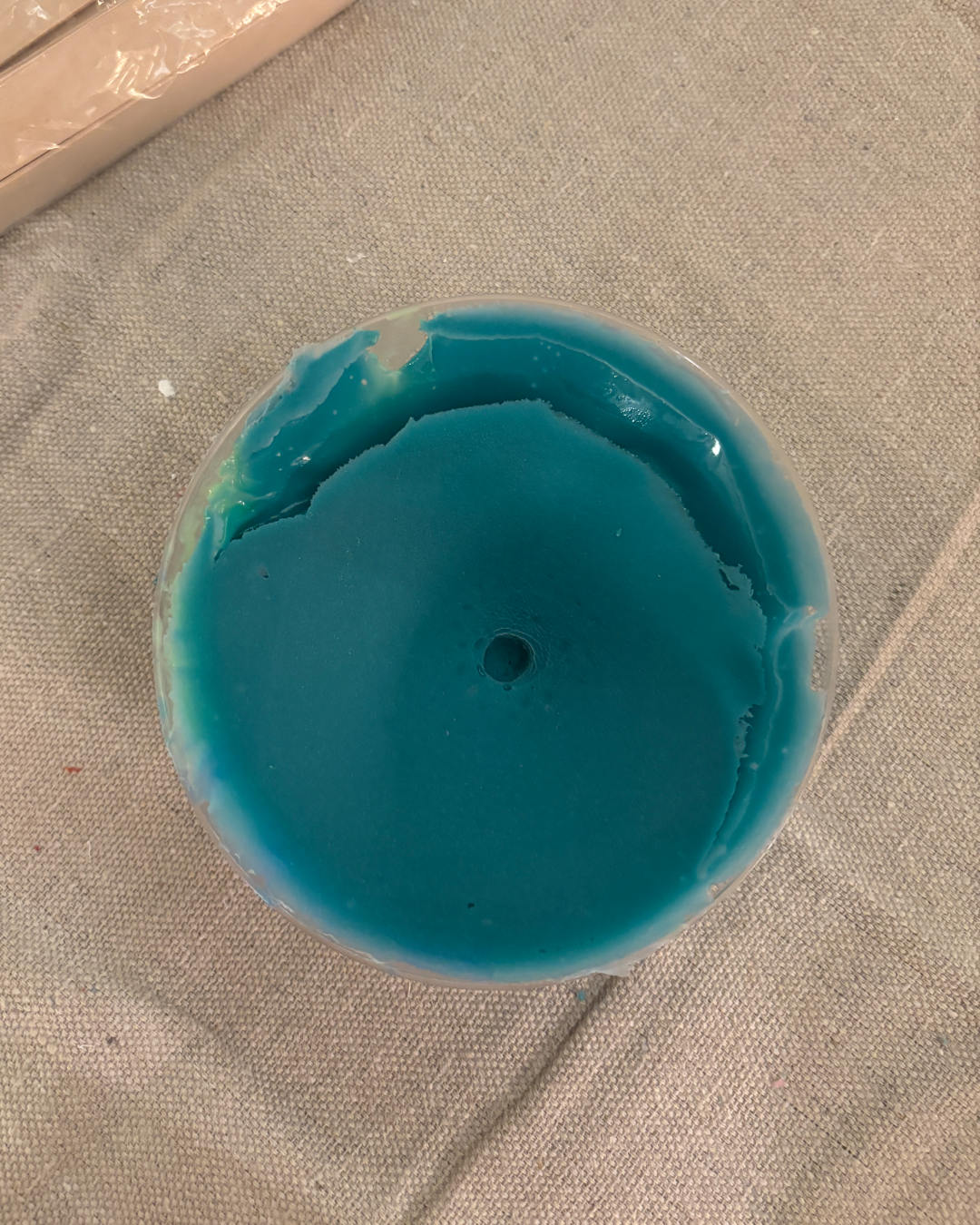

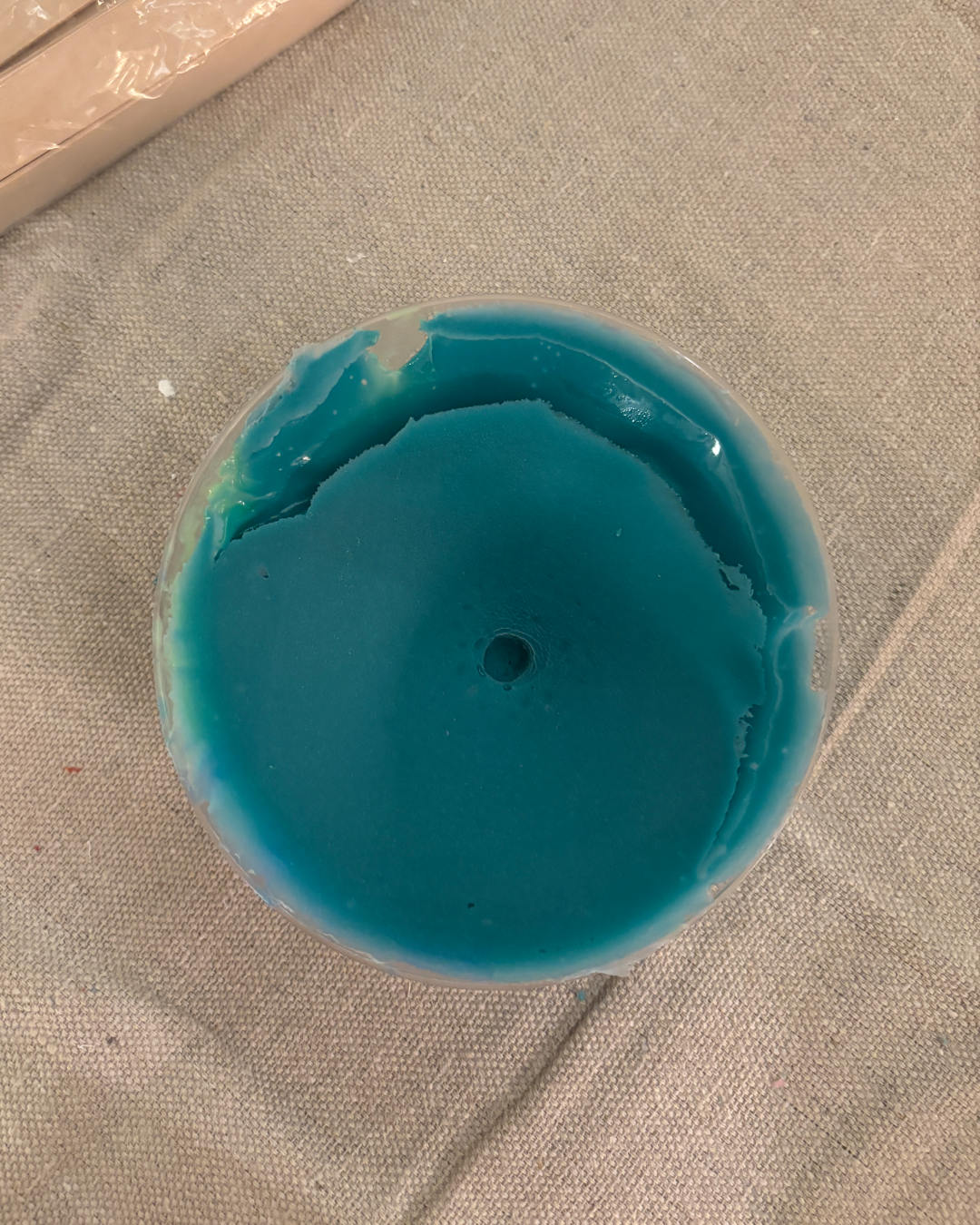

I sit down at the table while she weighs and mixes green and blue silicone in a small plastic bowl. While she prepares the concoction that my nipple will soon be engulfed in, we chat about our backgrounds, experiences at art school, and the dissonance between artist and audience. Fresh out of New York Fashion Week, themes of dissonance have been riddling my mind as of late. To be immersed in an industry built upon fantasy while we watch the world and democracy collapse in real time is, to put it simply, a mind fuck.

She tells me about her time at The Armory Show, the annual Fall art fair at New York’s Javits Center, just a few weeks prior. The very ethos of her practice fights systems of oppression and caste from which many folks in the art world—be them collectors, historians, or curators—benefit from in one way or another. It’s a dilemma many creative people face: how does one maintain a practice designed to counter these inequities, in an industry with an audience that is overwhelmingly built upon the very existence of such injustice?

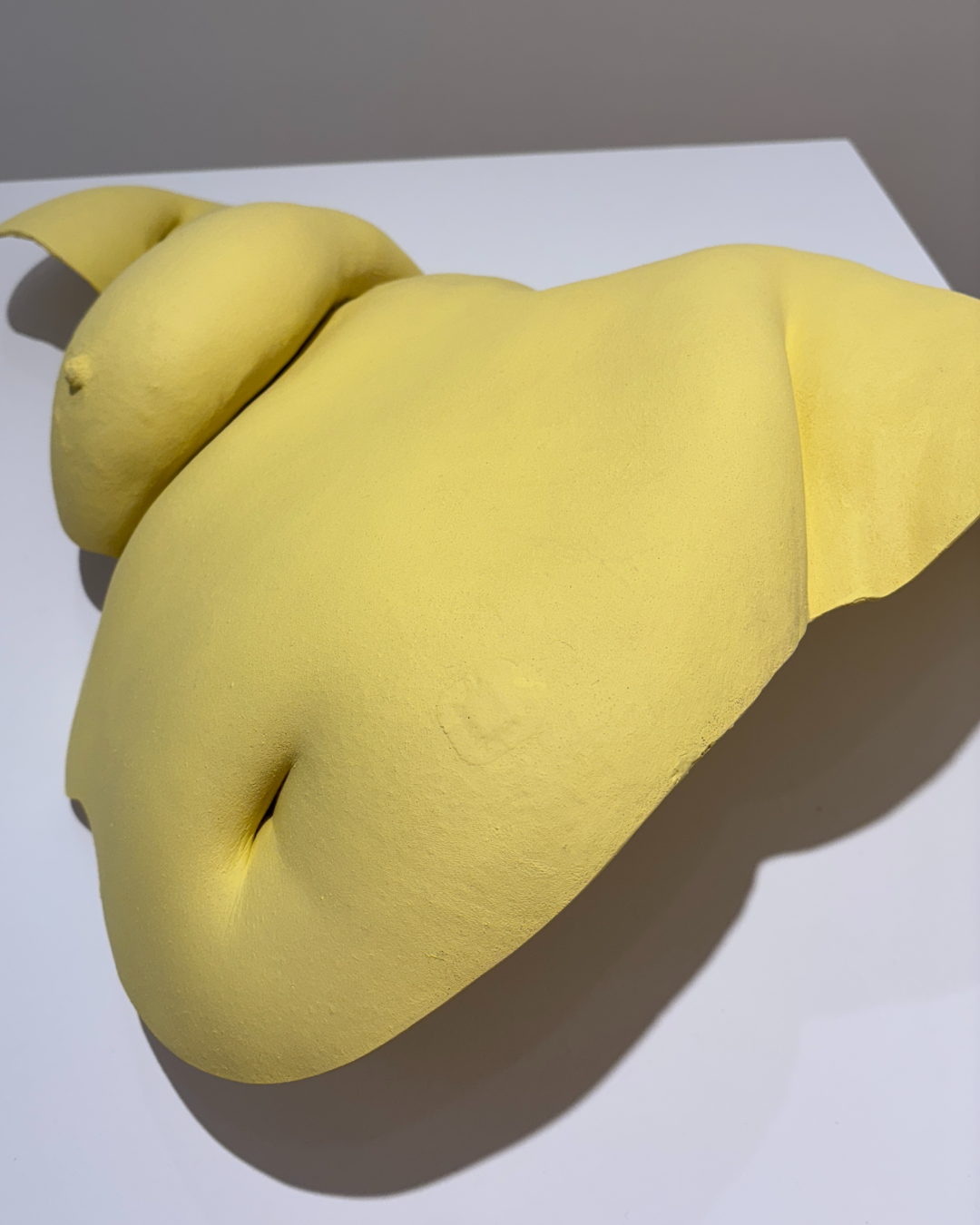

One way Japanwala has found to ground her practice against such cognitive dissonance, is to continue to place marginalized folks at the center of all she does. The femme and nonbinary bodies she sculpts are more than just muses in Japanwala’s world, they are home to the resistance and hope threaded throughout her entire body of work. Her Topographies have a striking quality, a textural nature that captivates your attention, drawing your eye across the sculptural landscapes from one silicone pore to another. However, the beauty in her work comes not just from the final form we are presented with, but the process in which it is procured.

Before I leave, she walks me through the gallery, telling me about her favorite details in the show and moving moments from her process. She offers a story of a woman who came in for a session who was at first frightened by the possibility of her stretch marks showing up in her final cast. By the time she left, she told Japanwala she hoped she would get to see them in the finished sculpted figure. I spend no more than 45 minutes of my Saturday morning with Misha Japanwala—five of those minutes spent bent over a table with my nipple resting in a small bowl of silicone—but that short period of time has already brought me to a point of reckoning with shame of my own. Maybe I just wanted to leave knowing that I embraced Japanwala’s mission in offering my body as is, imperfections and all. Maybe the five minute timer while I was doubled over was just the amount of time I needed for some self reflection, or the nipple casts in bowls lining the floor beside me offered a way out of the solitude of shame. Perhaps the mix of all three and the simple act of sitting in your body, steadfast in your presence, grounded by the physical sensation of the silicone mixture against your skin and the awareness of what that mixture is preserving, prompts what feels like a rewiring.

In the gallery she leads me to a yellow-bellied landscape, folded and sloped with the contours of its source figure. The person who calls this body home forgot to remove a bandage from their stomach before beginning their molding session, leaving a small square imprint protruding from their skin’s natural texture preserved in the cast. This so-called accident reaches the heart of the show, the essence of what Japanwala sought out to do with Sarsabzi. With her Topographies, she reframes these blemishes, the small imperfections spoiling our surfaces, with honor instead of shame, marks that celebrate our endless transformations, medals for the triumph that is life.

Misha Japanwala’s “Sarsabzi” is on display at Hannah Traore Gallery through December 6th, 2025. Ongoing nipple molding sessions are being held October 24-25 and November 14-15 on a first-come first-serve basis.