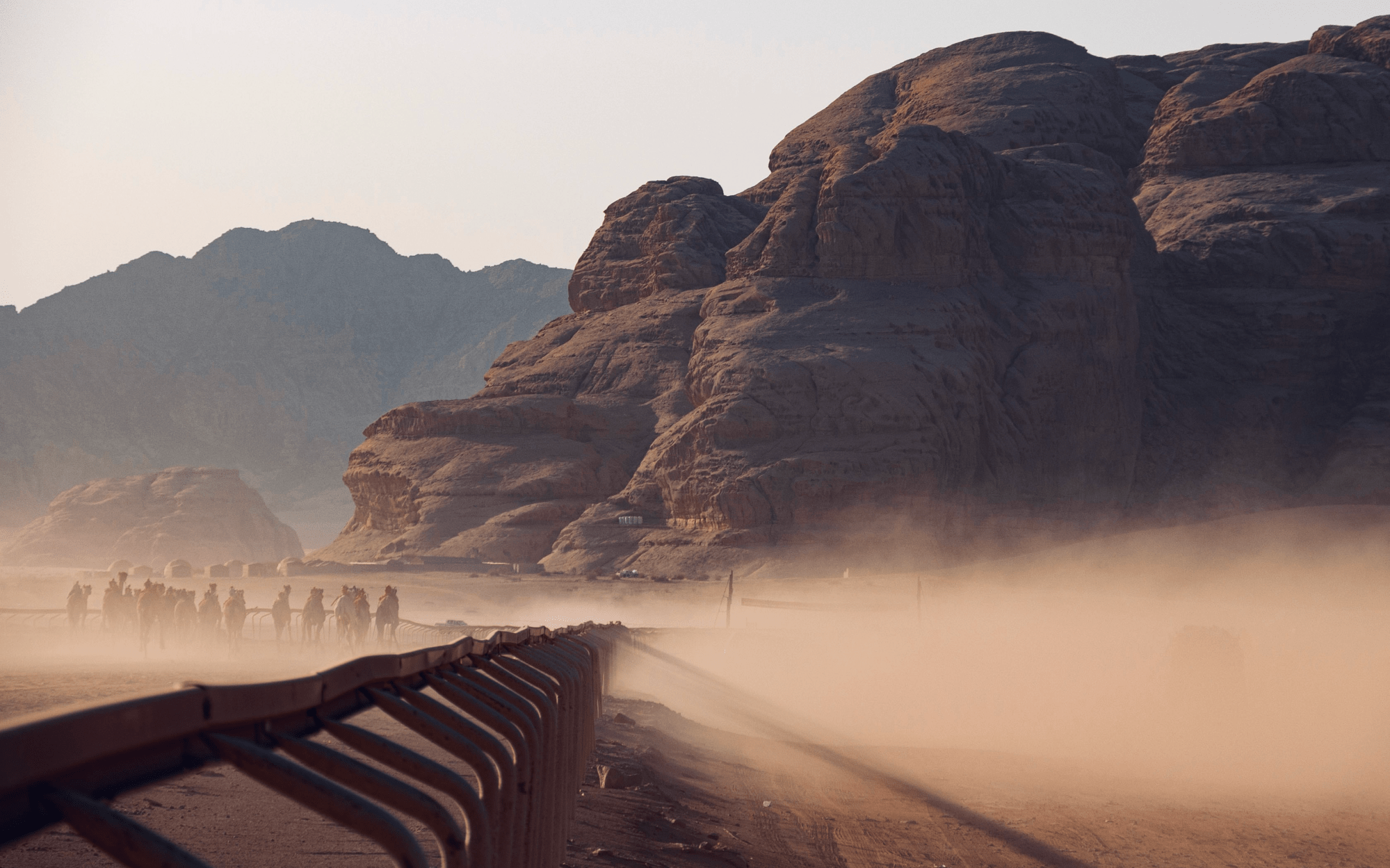

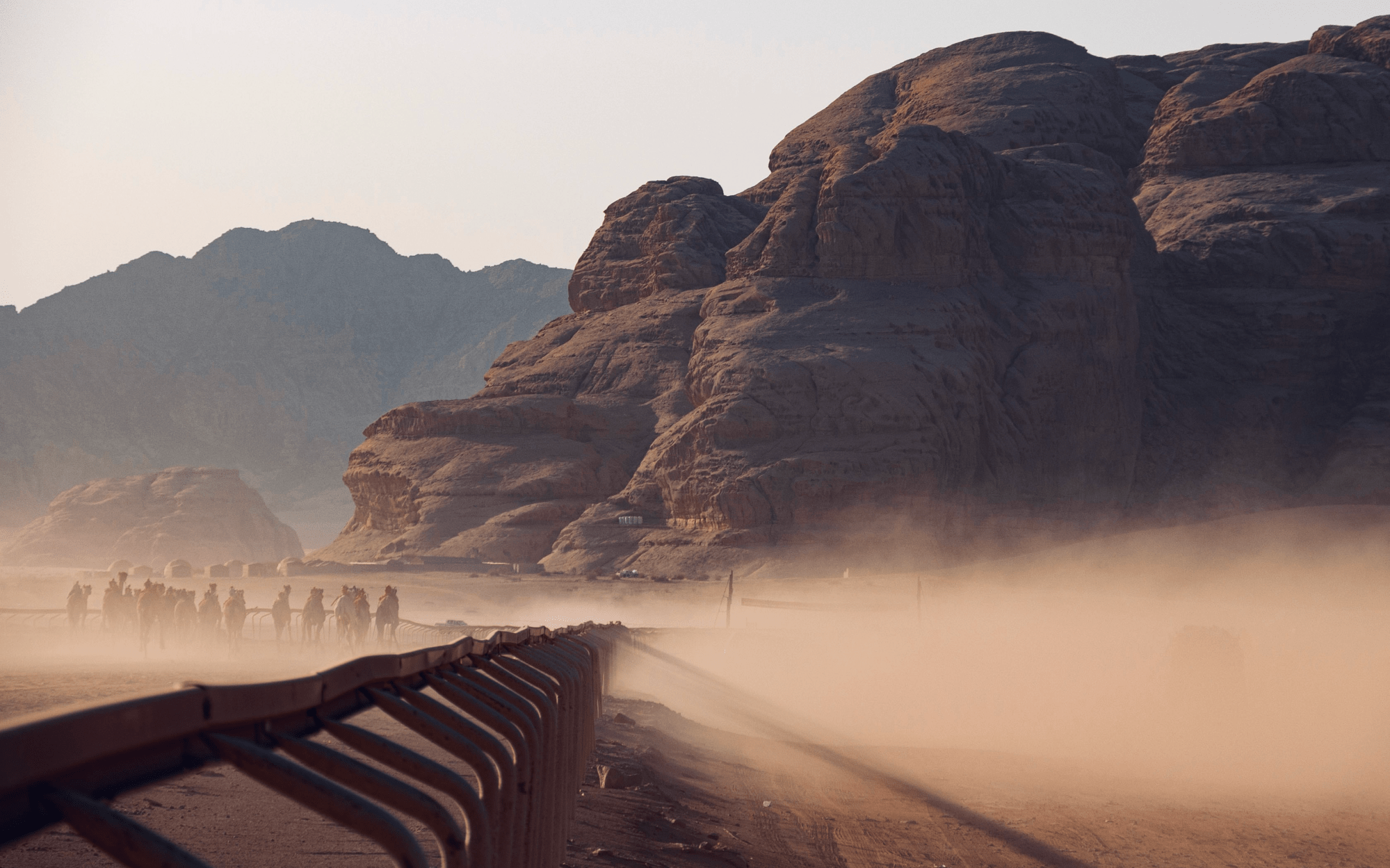

Every culture has traditions that connect present-day life to ancestral roots, but few remain as vivid and intact as Bedouin camel racing. Each autumn in Wadi Rum, the picturesque desert of Southern Jordan, Bedouin tribes gather for the Jordan Camel Racing Festival. Canadian-born Jordanian photographer Aziz Mousa has attended camel races with his family since childhood. A self-taught photographer and filmmaker with an academic background in psychopathology, he explores human behavior and identity at the intersection of tradition and modernity. Capturing the beating heart of this centuries-old practice, Mousa offers a firsthand look at cultural preservation, human connection, and the epic thrills of the races.

What does a day at this festival look like, from morning to night?

Each day begins at dawn. We sleep on the floor of our Bedouin tent and are woken at 6 a.m. by the gentle nudge of our elders’s walking stick. We drive straight to the track, following the camels for four kilometers across ten races. Some spectators watch from pickup truck beds, others from a large screen, and many gather on foot at the finish line.

After the races, we return to the tents, where competitors are welcomed with tea and food. As the sun sets, the camp comes alive. Coffee is brewed over the fire, young people cook, elders rest, meals are eaten by hand, and the nights stretch late as we welcome and visit neighbouring tribes. This rhythm continues for a week until the final day, when the winning tribe is announced and awarded an honorary sword from the crown prince along with a monetary prize.

How do you prepare the camels for the events?

First, we remove all ego, expectation, and control. We’re not the ones racing, the camels are. This understanding comes through Islam, reflected in Surah Al-Ghashiyah (88:17): “Do they not look at the camels, how they are created?” It reminds us to admire them and invoke blessing, protection, and gratitude.

The camels are not ours to dominate. They exist in their natural state, and our role is to care for them without harm. We groom and clean them, often decorating them with henna as a traditional way to honor their beauty. Feeding and hydration are carefully managed to provide energy without discomfort, and all equipment, including saddles and robotic speaker systems mounted on their backs, is thoroughly checked.

In the past, riders guided camels on horseback. Today, we follow them in our trucks, speaking through walkie-talkies while keeping our faces visible so the camels remain calm and focused. Before the race, we gently warm them up with the herd and ensure their family stays nearby, allowing them to return immediately to their dam and young afterwards.

How long has your family participated in this tradition?

The oldest record we have dates back to my late great-great-grandfather, who lived in what is now Saudi Arabia. The tradition itself goes back much further, as camel racing is a very ancient Bedouin practice. In our family, it has been passed down for more than 120 years.

What is your favorite part of the festival each year?

What I love most is how the festival preserves a way of life largely untouched by modern systems. For a brief period, everything mirrors the world of our ancestors. Despite modern obligations, everyone fully belongs to the present during that week.

Time feels suspended. There’s a natural, almost sacred rhythm where everyone contributes, creating a living expression of Bedouin communal life under one tent. Outsiders rarely experience this fully. Most participants are born into this social system and understand the responsibilities tied to age, family, and tribal roles. I see it as a deeply healing spiritual experience.

Why is it important to preserve traditions like this?

These traditions function as living systems of knowledge rather than symbolic performances. They carry ecological, social, and ethical wisdom about how to live with the land, care for animals, and organize communities outside of formal institutions. They were not preserved by chance—they endured because they were useful, meaningful, and adaptable under harsh conditions.

Historically, these festivals served as sport and social gatherings, requiring little material wealth, relying instead on skill, collective memory, and empathy between humans, animals, and the environment.

Preserving them is also an act of resistance against modern capitalism, which tends to commodify culture, competition, and even relationships. By maintaining our traditions, we protect forms of social cohesion, interdependence, and ethical responsibility that are increasingly rare yet deeply necessary today.

What barriers do you face in keeping these traditions alive?

One of the biggest challenges is modernization, particularly how urban life structures time, labor, and value. Education systems, work schedules, and economic pressures pull younger generations away from seasonal practices that require presence, patience, discipline, and continuity.

At the same time, Westernized frameworks often dismiss these traditions as outdated rather than recognizing them as living systems of knowledge. The issue isn’t a lack of care, but a social structure that makes transmission increasingly difficult as young people try to build stable lives in modern cities.

What makes this tradition so special to you and your family?

Each time I participate, it feels like reuniting with my ancestors, as if I can enter their world. I’ve found myself connecting the most with my great-grandfather, discovering similarities between us through the stories I grew up hearing.

As elders pass and fewer links to the past remain, the tradition teaches presence and intention. It reminds me to create memories and preserve customs for the next generation. For me, this isn’t just nostalgic, it’s transformational. Each year, it shapes my identity, helps me navigate personal challenges, and reminds me of where I come from and the strength I carry forward.

Do you have a favorite among your family’s camels?

It’s hard to choose, as each one is special in their own way, but Amal bint Moheeb, a 7-year-old camel passed down through five generations and is near retirement. Camels typically begin racing at 2–3 years old and retire around 8 or 9.

In Arabic, “Amal” means Hope, and “bint Moheeb” means Daughter of Moheeb, with Moheeb meaning the Encourager or the Inspirer. She has lived up to her name, representing hope throughout her life and bringing us many victories on the track.