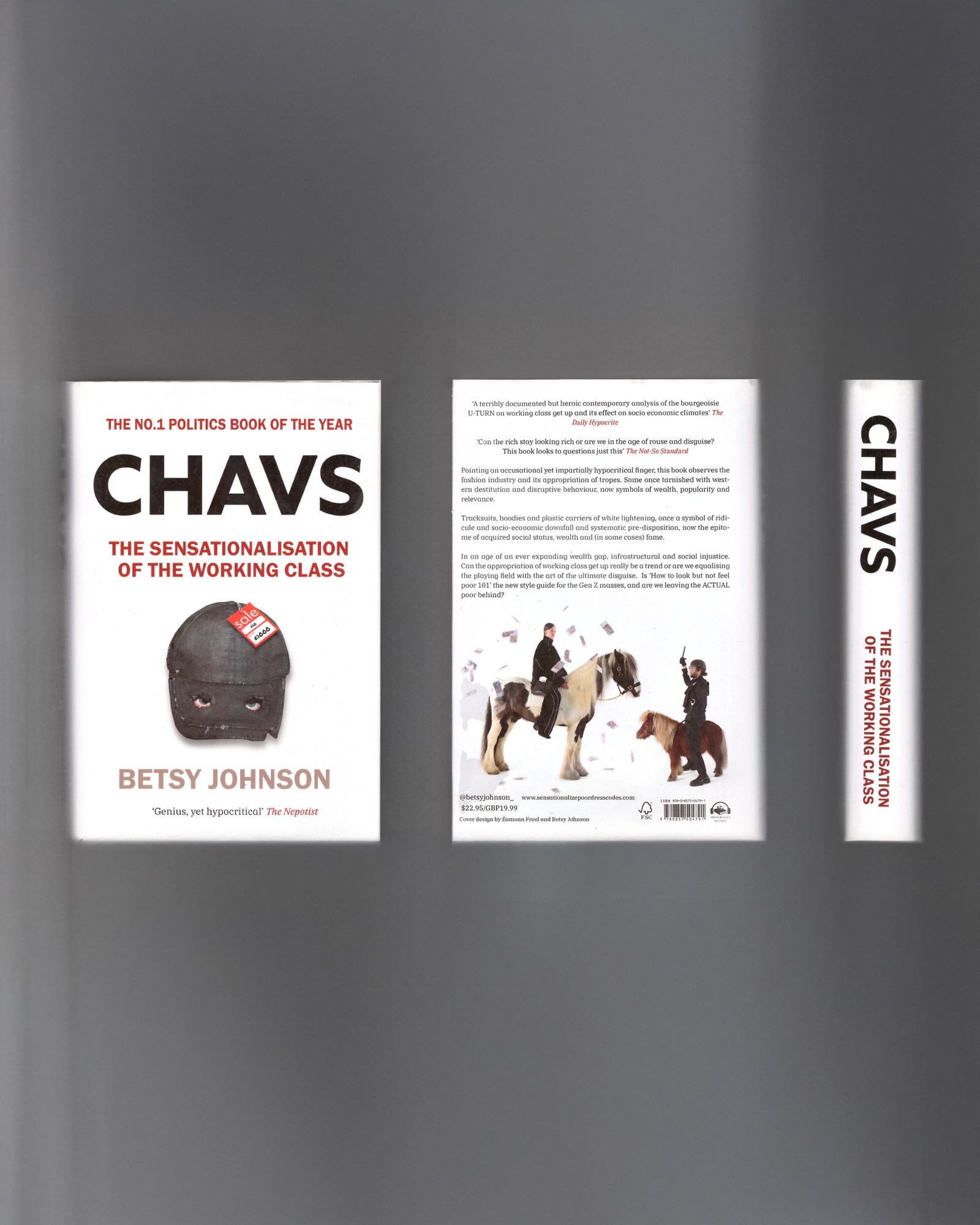

You’ve probably seen the work before you knew who was behind it. A series of images circulating online. Something off-beat in the feed that feels too deliberate to be trend-driven, too strange to be accidental. Shots that linger just long enough to make you uncomfortable. That visual language belongs to Betsy Johnson. And no, not the fashion designer. Different spelling. Different universe.

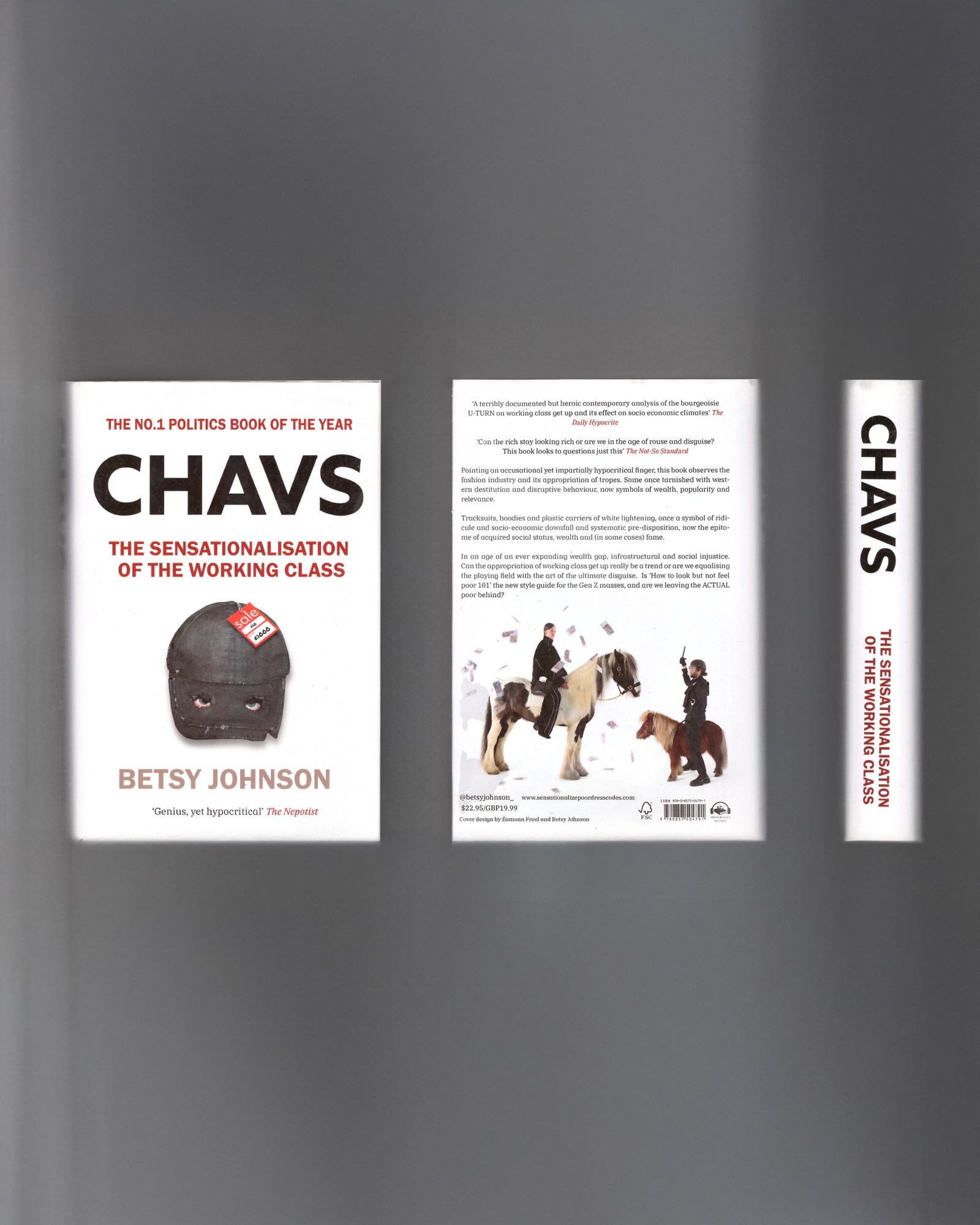

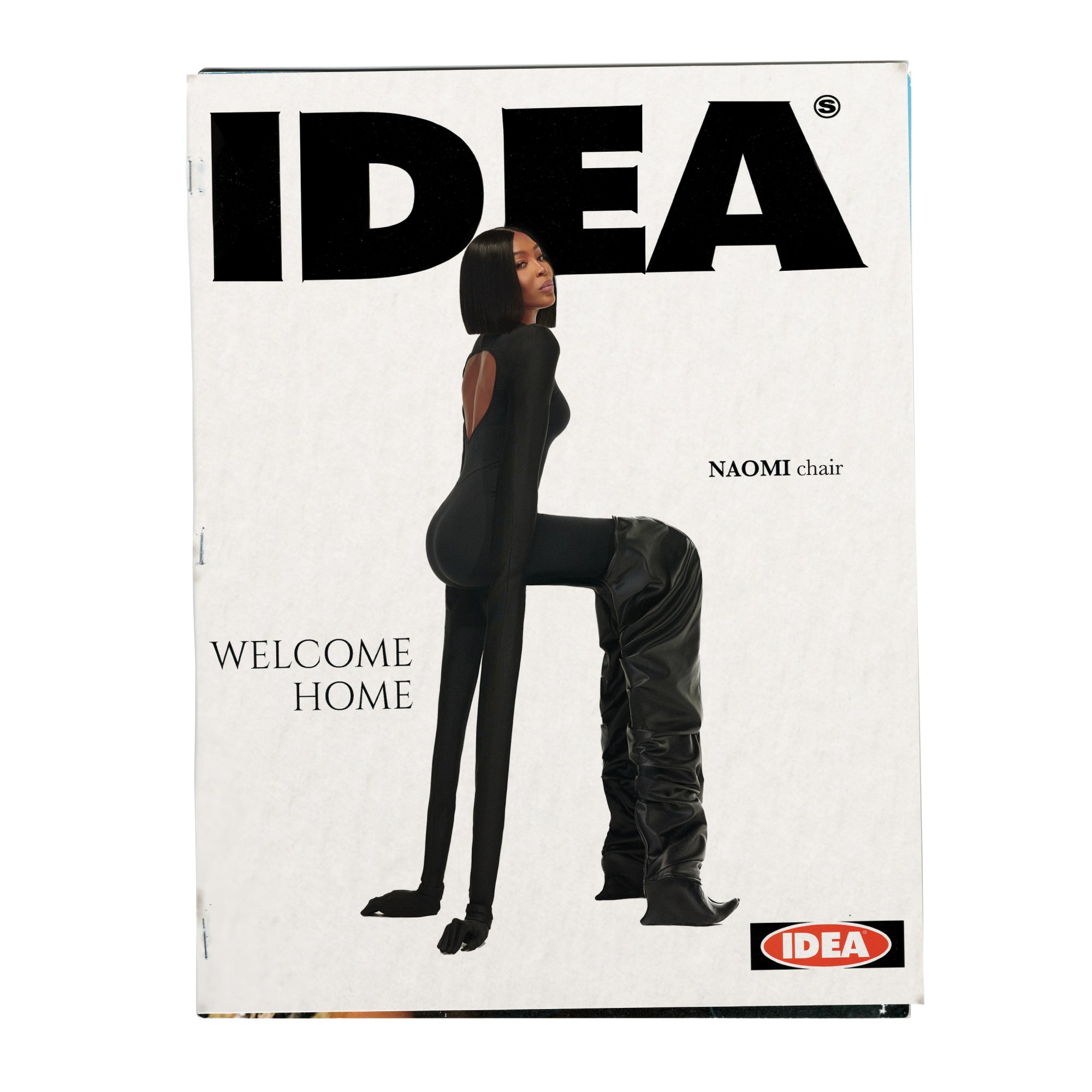

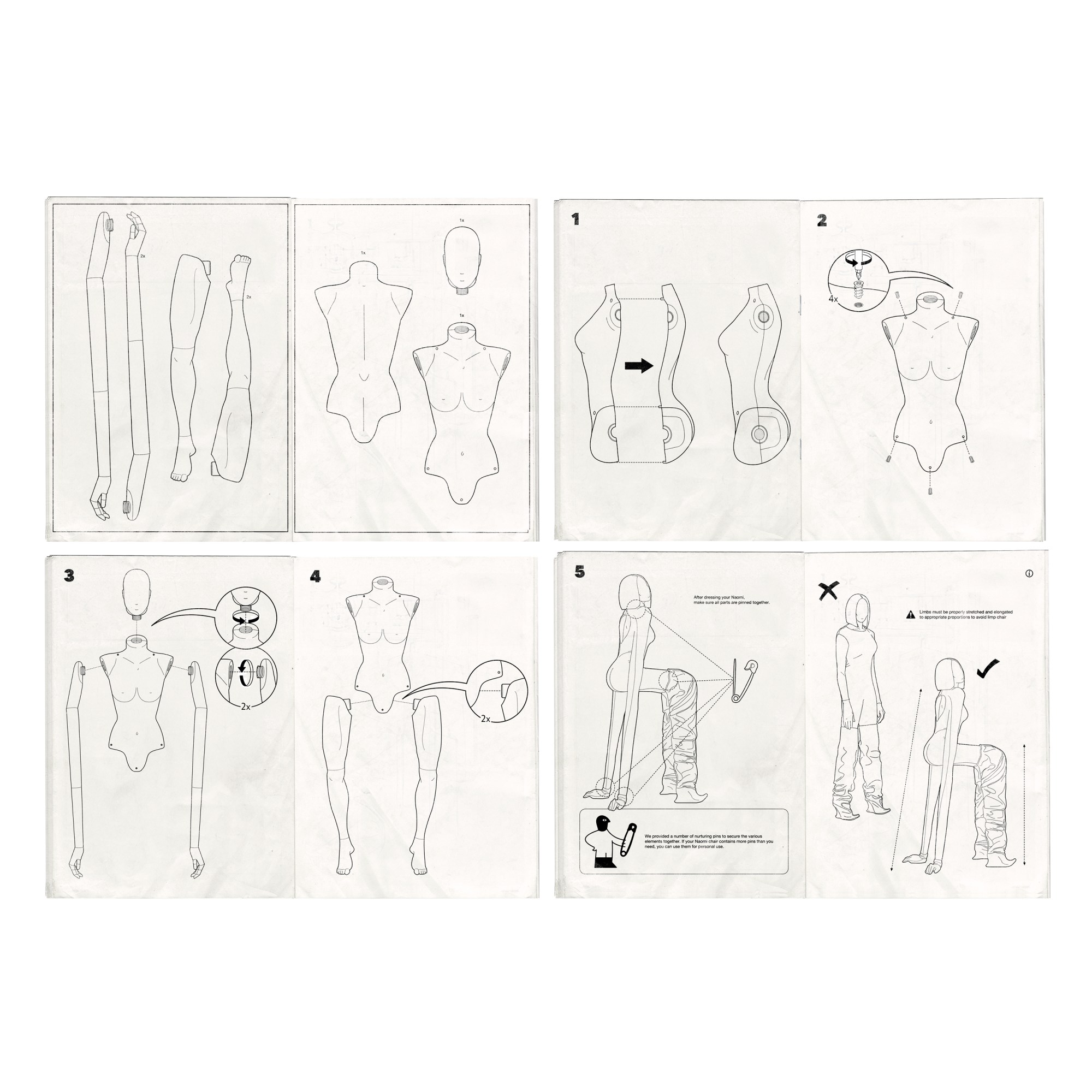

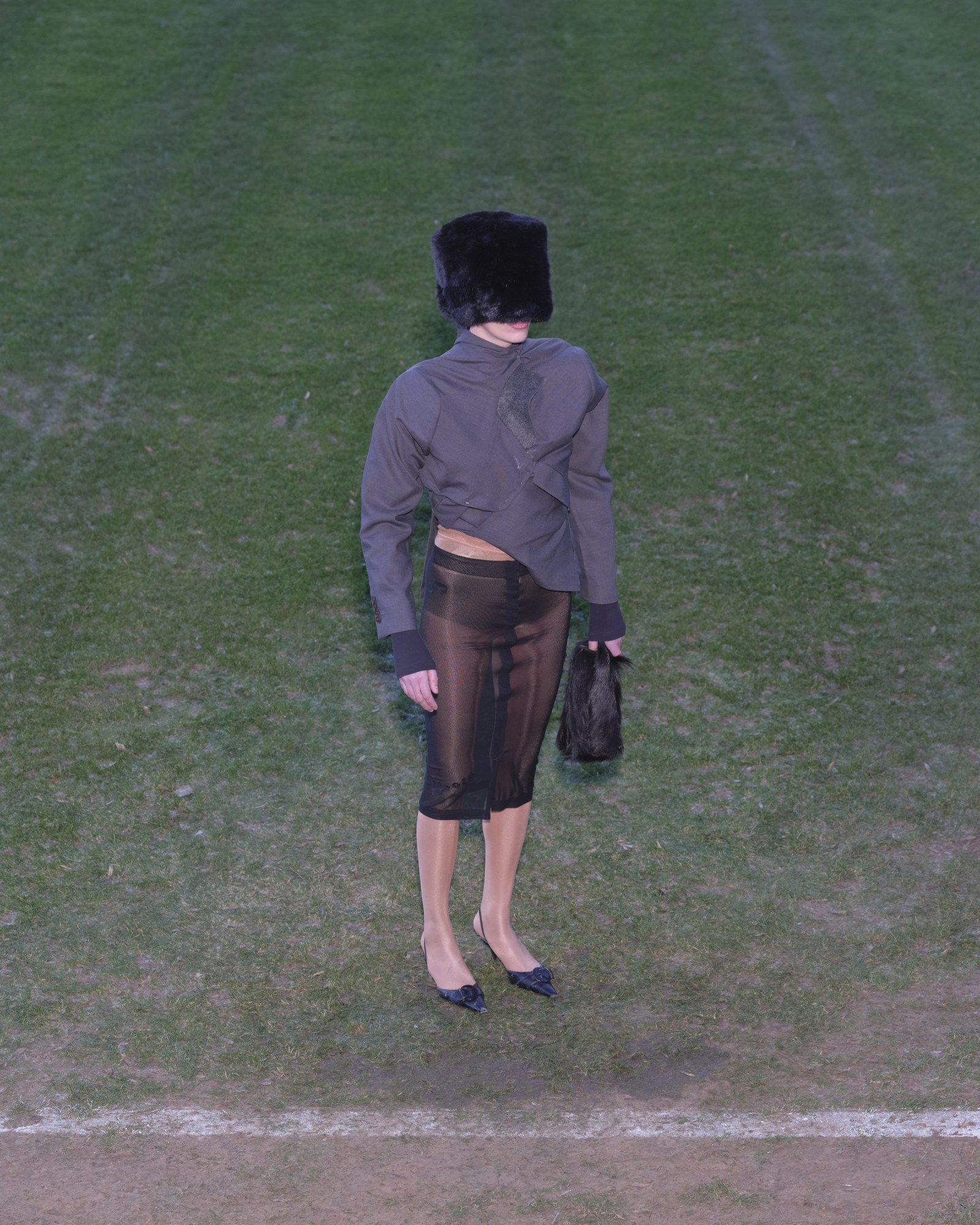

Johnson is an artist, creative director, and stylist whose practice moves fluidly across fashion, art, and publishing without ever losing its center of gravity. Her work is moody and conceptual but never cold. Strange, but human. There’s humor embedded in the seriousness, and seriousness beneath the humor. She’s worked with Ye, collaborated with Balenciaga, and shot for cult magazines like Re-Edition, as well as curating exhibitions and experimenting with garment design. But credentials aren’t the point. Johnson’s work resists résumé logic. It’s less interested in access than in excavation: how taste is constructed, how class is signaled, how desire is styled into something legible, sellable, or suspect.

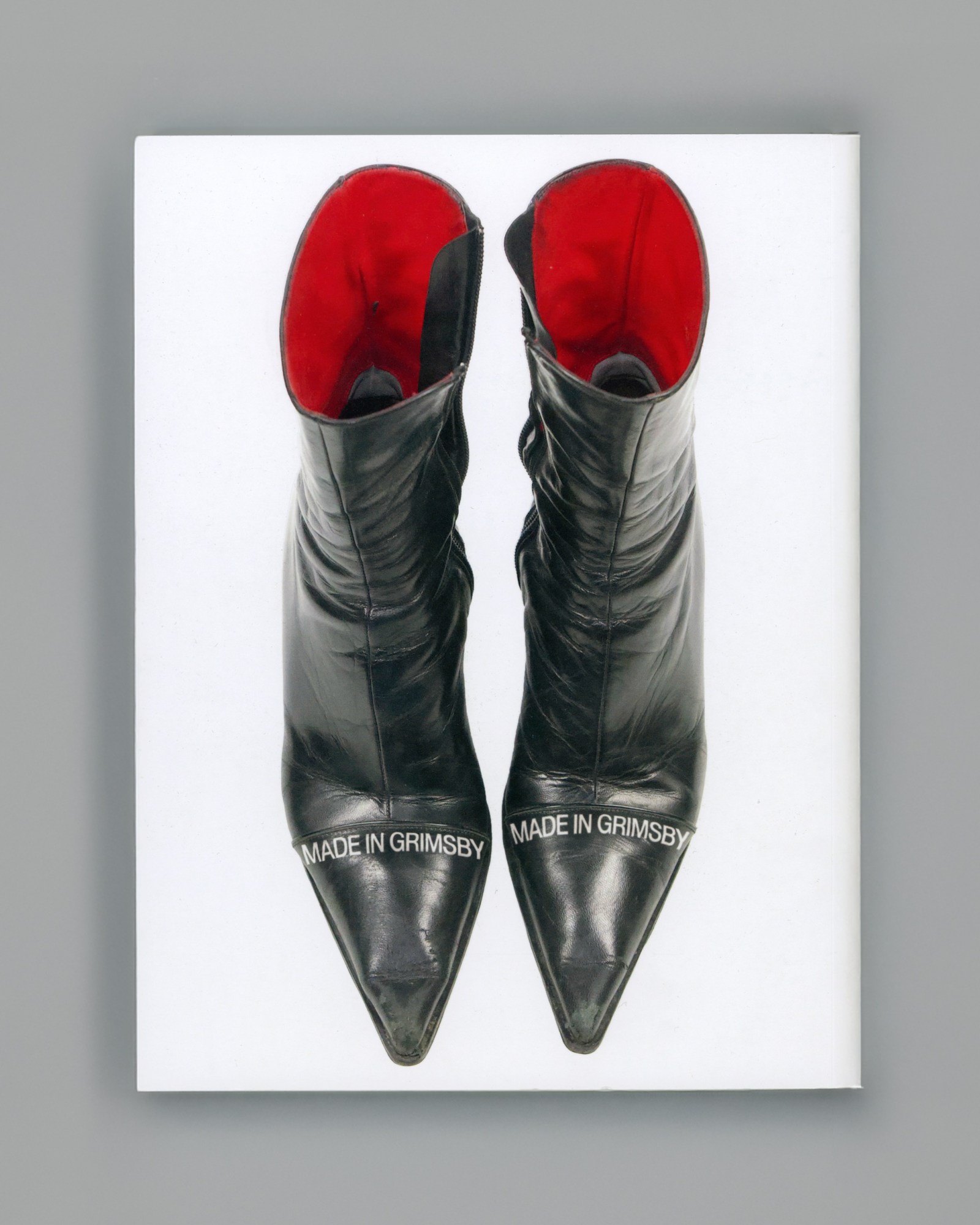

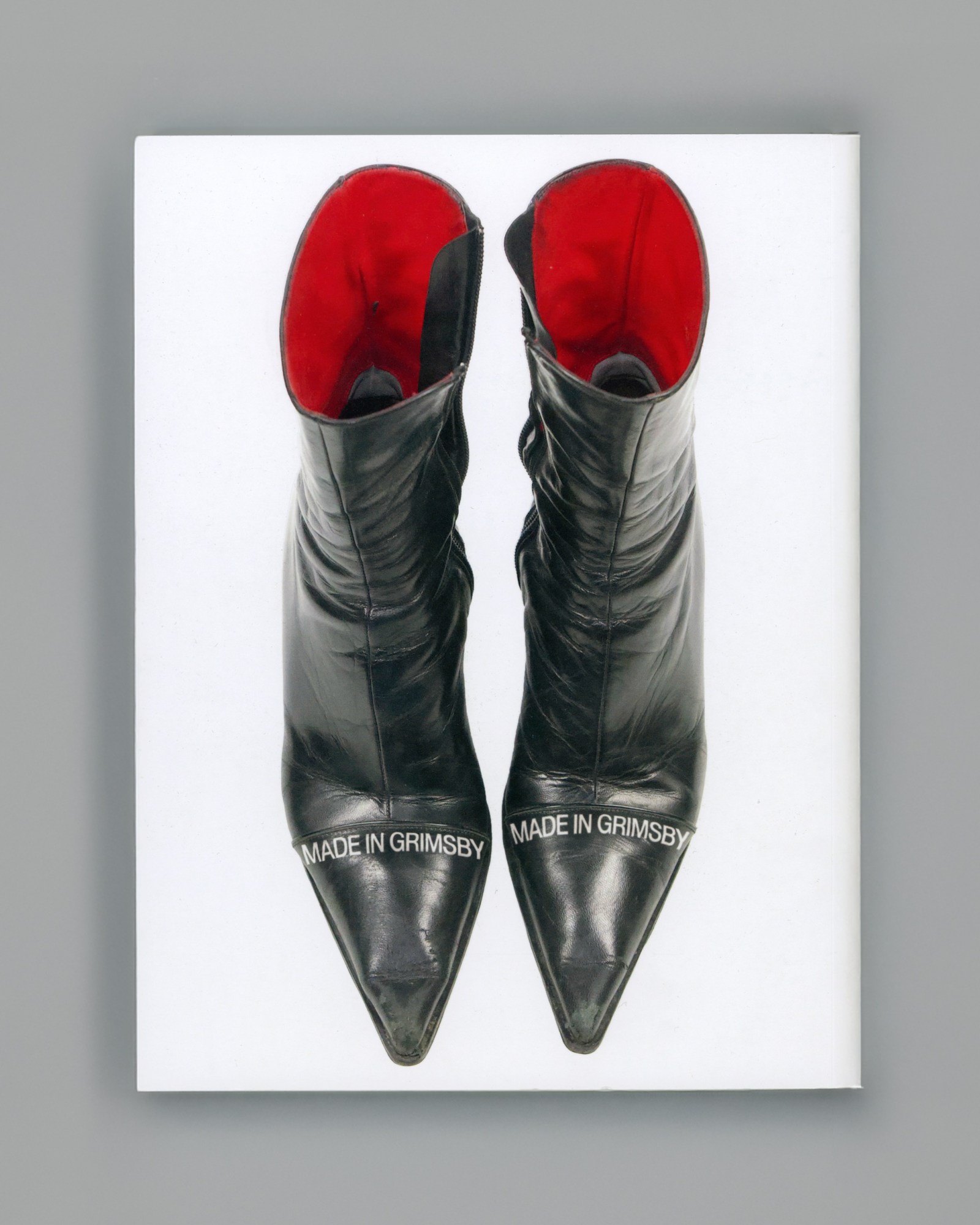

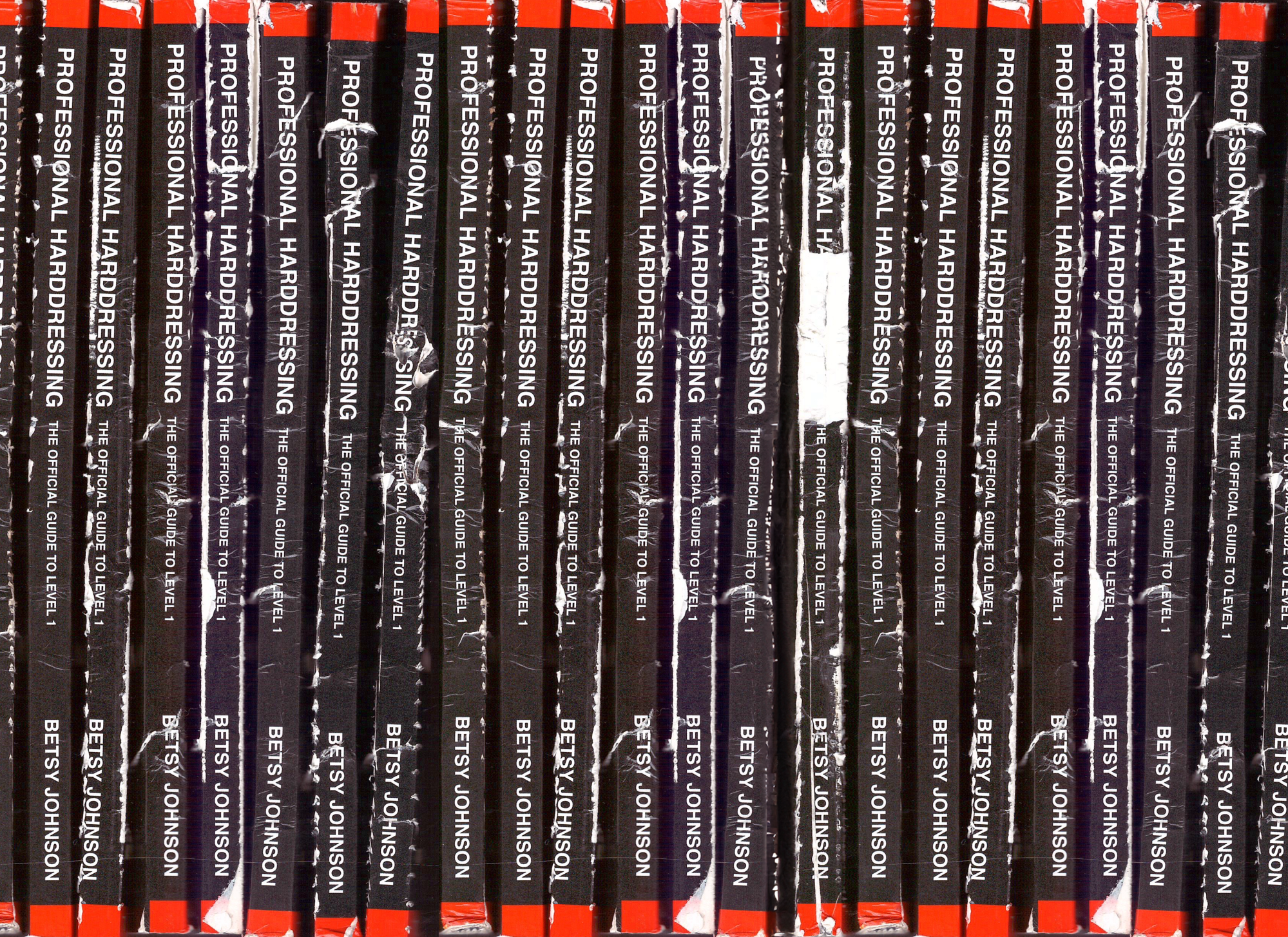

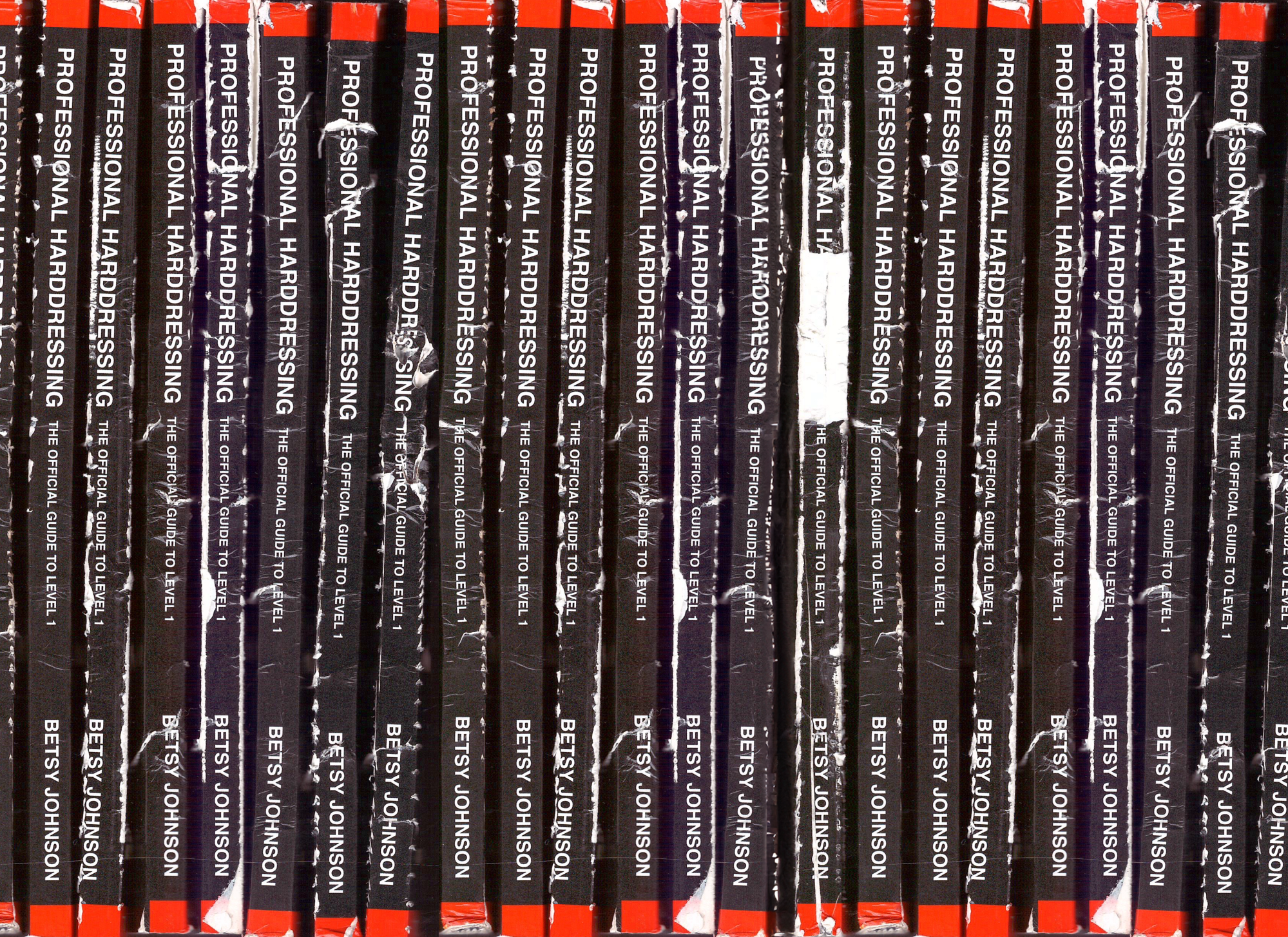

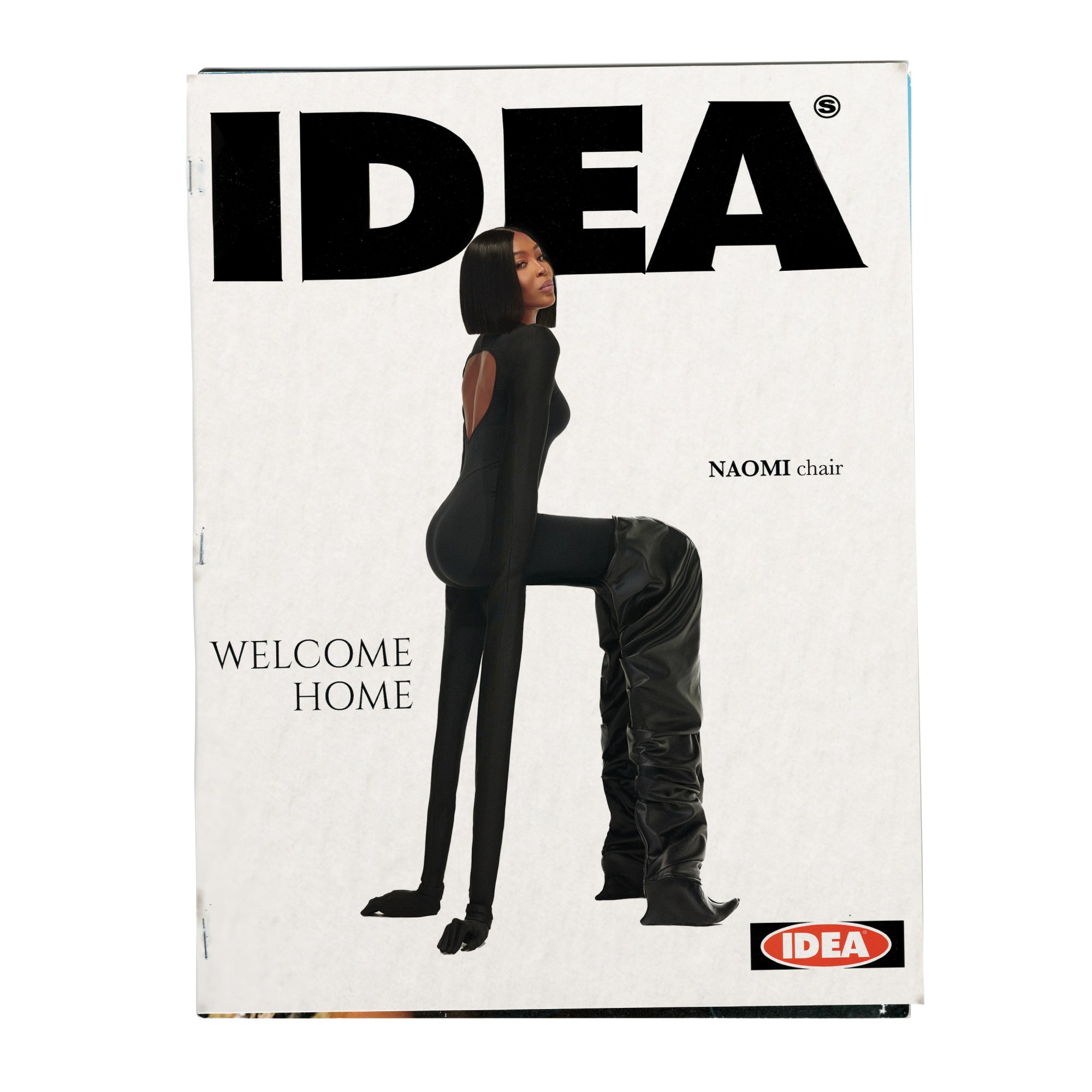

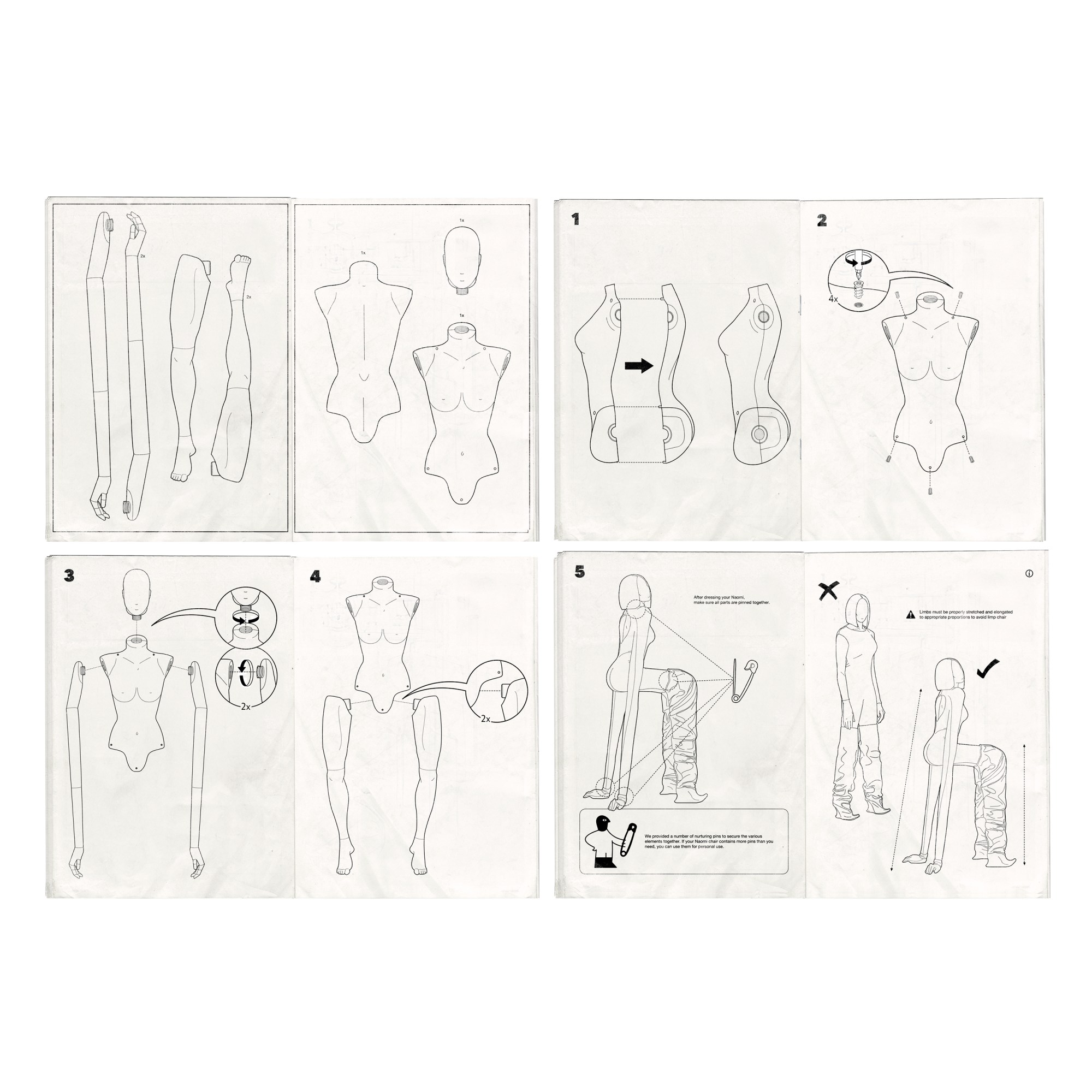

Those questions sit at the heart of her new book, REVISION. Documenting her creative evolution since leaving Grimsby in northern England, the 152-page hardcover brings together six years of personal projects, unpublished work, archival material, notes, and shoot relics from 2018 to 2024. It reads less like a monograph and more like a working archive left intentionally open.

Below, Johnson breaks down the thinking behind REVISION and explains why uncertainty isn’t a flaw in creative practice, but its foundation.

Alex Kessler: Where did your earliest interest in fashion and clothes come from?

Betsy Johnson: I grew up around a lot of uniformity. School uniform, military uniform, sports kits. My family mostly worked in trades. My auntie made incredible wedding gowns. That’s where I first saw sewing.

I wore hand-me-downs and charity shop clothes. My mum always let me choose, even when it looked like a mess. My dad was strict about looking “sharp.” There was tension and freedom in clothes. A space to conform, or be creative, or be of service. I learned early I could change how people perceived me through clothing.

You began as a stylist. What did that teach you?

Up-cycling taught me styling before I knew it was a role. It taught me silhouette, how to make something undesirable feel desirable with a shift of context. It taught me narrative control. Seeing potential rather than face value. Desire, curation, and edit are everything. That’s still fundamental to how I work.

When did photography become central?

I was always observing. Filming my family, shooting on disposable cameras. Editorially, I started shooting myself because no one wanted to shoot with me. There’s a lot of terrible work you’ll never see. But trial and error is how you learn.

REVISION follows your departure from northern England. How did that change your thinking around class and ambition?

I was raised politically aware and very angry. I thought the problem was “the rich.” Leaving home gave me perspective. I realized the issue wasn’t the middle. It was access to the rooms where decisions get made.

That realization forced a shift. I had to change how I moved through the world. I reinvented myself. Betsy Johnson became a version of me that could survive difficult business and social environments. Betsy feels and questions. Betsy Johnson takes action.

Why release unpublished and private material now?

I have boxes of notebooks, notes, relics. I wanted to show the practice behind the work. The human, messy thinking. Creativity isn’t a god-given gift. It’s a discipline. Letting go of unreleased work was necessary, creatively and emotionally.

How do you decide which role to occupy on a project?

The author or lens bias is real. Sometimes someone else’s perspective is crucial. Sometimes it’s more important to take control yourself. Ideally, authorship dissolves and the work becomes a collective outcome.

Your work interrogates commodity culture from inside fashion. How do you hold that tension?

I didn’t set out to critique. I’m excavating my own thoughts in an ironic space. Over time, the mission shifts from commentary to ideas around systemic change. With power comes the instinct to get quieter, not louder.

Why are unresolved ideas so important to you?

The most unresolved ideas are the only ones worth exploring aesthetically. They’re still questions. They make me rethink things every time.

You’ve said you hope the book resonates with students. What do you wish you’d known earlier?

That there was a route for me. That principles and values matter more than goals. I also wish I’d been taught money. Financial literacy is gatekept and keeps working-class voices out of the conversation. That has to change.

Looking back, what’s changed most?

I’ve worked through a lot of anger. Now the focus is on building ways of working, not just images. Long-term change over aesthetic disruption. Community over moments.

What’s next?

Systemise our work, ironically. Build better structures. Stay curious. Work across new mediums.

Ok… last one. Drop your reading list!

Be 2.0 by Jim Collins

Atomic Habits by James Clear

The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki

Mindset by Carol Dweck

The Power of Thinking Big by David Schwartz

The Life-Changing Magic of Not Giving a F*ck by Sarah Knight Do It Today by Darius Foroux