written by ALEX FRANK

photography BOBBY DOHERTY

styling JULIAN LOUIE

Even from 3,000 miles away, Jack Antonoff is a jittery presence. He’s FaceTimed me from a car in the parking lot of a Los Angeles studio; when his sweetly nerdy visage surfaces on my cold New York screen, he’s looking not at the camera but instead scanning the contents of a paper bag in the passenger seat. Before I’ve even asked my first real question, he gets out of his car to meet who he thinks is a Caviar driver with a coffee delivery. It turns out to be a colleague heading in to meet him at the studio. He sits back down, his neck swivelling like a bird every 15 seconds to check for the Caviar driver, then, spotting someone, gets up again. This time it is a delivery driver, but for someone else in the building, so he points him in the right direction and gets back in his car, the slender tip of his index finger swiping our screen to check for notifications. Some version of this Larry David-esque interaction goes on for quite a while—Jack grabbing his phone and exiting the car, Jack reentering the car and propping the phone back on the dashboard, Jack craning his neck to search for his Caviar—and by the time our conversation is over, he still hasn’t even gotten his coffee.

Yes, this is the man who’s had perhaps the most focused run of successful music of any producer in the last decade. Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey, Lorde, Sabrina Carpenter—Antonoff has worked on these defining giants’ most popular and critically-acclaimed albums, known for coaxing deeply introspective and passionately probing songs about inner turmoil and broken hearts and exciting nights and new relationships, songs that have become anthems for every music lover under the age of about 50. Producers like Antonoff do any number of things for artists, depending on the specifics of a project, from helping co-write from scratch to just polishing what is almost finished. And though it’s hard to say what, exactly, has made Antonoff such a powerful force—a recurring theme of our conversation is his insistence that he has no fucking clue why his work succeeds—his restlessness seems part of it: the animating intensity of always seeking, always searching, never quite comfortable enough to rest on your laurels or, in both a literal and figurative sense, relax fully into the driver’s seat. “I think a large part of what I do,” he says, “is just feeling like I’m on the edge of… something.”

Aside from his production work—which includes a recently-announced new single from Lana called “White feather-hawk tail deer hunter”—Antonoff has his own project called Bleachers, for which he will release a new album this spring. The collection of 11 songs is a deeply felt meditation on the messy days of yore, a brooding journey through the big decisions and important relationships of his younger years. His lyrics drift back towards the first time he left his parents’ home in New Jersey to go on tour, and then further still; on the opening track “Sideways,” he alludes to the legacy of his ancestors, Eastern European Jews, “the ones that survived and got out.” Here is the dizzying way he describes the heart of the album:

“I don’t feel part of the past, and I feel part of a version of the future, but not necessarily this one. When you write, you’re not writing things you know—there are these strange feelings, and then all of a sudden you start to realise, ‘Oh, I’m really humming on a thing here, and I got to figure that out,’ a lot like [psycho]analysis. And so, I started realising I’ve just been obsessively trying to figure out… all the cornerstones. It’s like, I’ve presented this mountain of issues, but at the end of the day, it’s mostly love songs about the few key figures in your life—all different, all the same—who make it bearable.”

If that seems like a lot to take in, it can be helpful to slow down and trace the more concrete facts of Antonoff’s life. Born and raised in New Jersey—where he still lives today with his wife, the actress Margaret Qualley—he had a loving family but an innate sense of dread: When he was 5, his younger sister Sarah was born and quickly developed brain cancer. (Antonoff also has an older sister, Rachel, a fashion designer.) “We lived what seemed, from the outside, a normal life, because she didn’t appear different. But there was something in the household which wasn’t the most normal. There was a lot of dissonance.” She died when he was 18. “There’s a long period in my life where I was working on the grief puzzle. It’s really interwoven into this album.” Indeed, these new Bleachers songs—with titles like “Just Don’t Wanna Be Lonely” and “Can’t Believe You’re Gone”—are haunted by an unmistakable melancholy, and Antonoff has said in the past that everything he makes is in some way about his sister, the pain of reaching for answers to unanswerable sorrow. “The ghostly part, this thing that you chase forever,” he says, “you go through these things, and then you chase them down, and then you get there, and you’re like, ‘Alright, I guess I’ll go to lunch.’”

An avowed Bruce Springsteen fanatic, Antonoff came up in noisy, messy rock bands, playing tiny venues and driving around New Jersey in a van. But even then, he possessed a sense of aspiration. In 2011, he and his then-band, Fun., sought out producer Jeff Bhasker—already famous for his work with Kanye West and Beyoncé—and convinced him to collaborate on a song called “We Are Young.” It became an unexpectedly massive hit, and in its fidgety pulse, you can hear the blueprint of Antonoff’s future genius: a braiding of indie textures with pop instincts, capped by the sentimental swell and crash of a huge, irresistible chorus. Just as Antonoff began flirting with a more straightforward pop sound, he met Taylor Swift at an awards show, where the two bonded over a shared love of the 1980s new-wave duo Yazoo. In 2014, the connection led to a production credit on 1989, Swift’s glossy, massively successful collection of synth-pop that wiped away the last vestiges of country from her sound. That same year, Antonoff released Strange Desire, his first album with Bleachers, and told podcaster Marc Maron that he was largely disappointed by the mainstream music of the moment; he wanted, he said prophetically, to be “the person who changes it.”

A goal like that might’ve sounded absurd in 2014, but with the benefit of 12 years, it’s wild to realise he’s largely accomplished it. Antonoff has since helped Swift finesse epoch-defining albums like folklore and Midnights, and specifically many of her most popular and addictive singles, including “Cruel Summer” and “Anti-Hero.” (He is absent from Swift’s most recent album, The Life of a Showgirl, a fact his publicist preemptively requests that I not ask him about, despite the fact that I had no intention of doing so anyway.) If the scattered post-monoculture landscape of pop can be said to have a defining “sound,” it’s somewhere in the heavy drums and synthy sheen and folky reverb of Antonoff’s collaborative masterpieces: Lorde’s sleek, sincere Melodrama; Sabrina Carpenter’s wry, winking Man’s Best Friend; and, most notably—at least for this writer—Lana Del Rey’s mythic Norman Fucking Rockwell!, which, in its graceful blend of zeitgeist and poeticism and awesome beauty, occupies a space for Millennials that, say, Joni Mitchell’s Blue might for Boomers. “Sometimes you make things to escape to, and sometimes you make things that explain what it’s like to be here now—Lana has a very specific gift for that,” he says. “We have something in common, a dedication to searching for it. Loving all the meandering paths you take to finding that thing.”

“There’s so many people out there yelling how the sausage is made that it’s increasingly hard for people to imagine that it is just magic.”

jack antonoff

And what is Antonoff’s particular thing, the one that allows him to do such sorcery with this roster of (mostly) female icons? Listening to those Lorde and Lana and Taylor albums back-to-back, there are some unifying principles: a pop-ness that’s always interspersed with something indie-er; a sincerity in the lyrics that, handled without care, could border on schmaltz; a genius for structuring choruses like cresting ocean waves, each one swooning sparklingly towards the sun, giving everything the warm, sing-along quality of an anthem. Collaborators like Maren Morris have said that he brings a good vibe to the studio, and, as a woman in the misogynistic world of music, that he’s the rare man who never condescends—who gives women space to feel vulnerable and raw and experimental. “I think he reminds me of why I wanted to make things with other people in the first place,” Hayley Williams, the Paramore lead and Antonoff’s longtime friend and collaborator, tells me. “His frenetic studio energy is a comfort to me, and it shields me from my own creative seriousness. In fact, it’s kind of hard to stop being idiots and just work. But then we reenter the vortex and come back out with another song.” Whatever Antonoff’s singular gift, despite my repeated attempts to get to the bottom of it, he’s unable, or at least unwilling, to share the recipe. “There’s so many people out there yelling how the sausage is made,” he says, “that it’s increasingly hard for people to imagine that it is just magic.”

Still, even inadvertently, I’ll discover by the end of our conversation one aspect of that “magic.” The new Bleachers album is laced with references to Qualley, and when I ask what married life has given him (a sense of security, perhaps?) Antonoff gently turns the question back on me, the way he might in a studio, luring a song out of someone else.

I tell him I’m heartbroken, still lingering in the bittersweet afterglow of a relationship whose comfort I haven’t yet learned to let go of. He says that he knows exactly how I feel and then puts into words, better than I ever could, the exact easement I’m seeking in my own neurotic dating life. “The second I met my partner,” he tells me, “a cynical part of me died—the very Jewish, analytical, endlessly-weighing-everything part.” What replaced it, he reassures me, wasn’t certainty so much as peace, the relief of no longer having to argue with himself about whether he’ll end up where he needs to be. Then, as we say goodbye, the jitteriness of FaceTime and the 3,000 miles between us briefly fall away. He looks straight into the camera and offers a small, sincere note of solace: “I hope you get through it all, okay?” And as the FaceTime dies, those are the words that linger, less like advice than the quiet echo of a lovesick pop song, one that I’d be happy to have gotten stuck in my head, on loop until it starts to feel like it was made just for me.

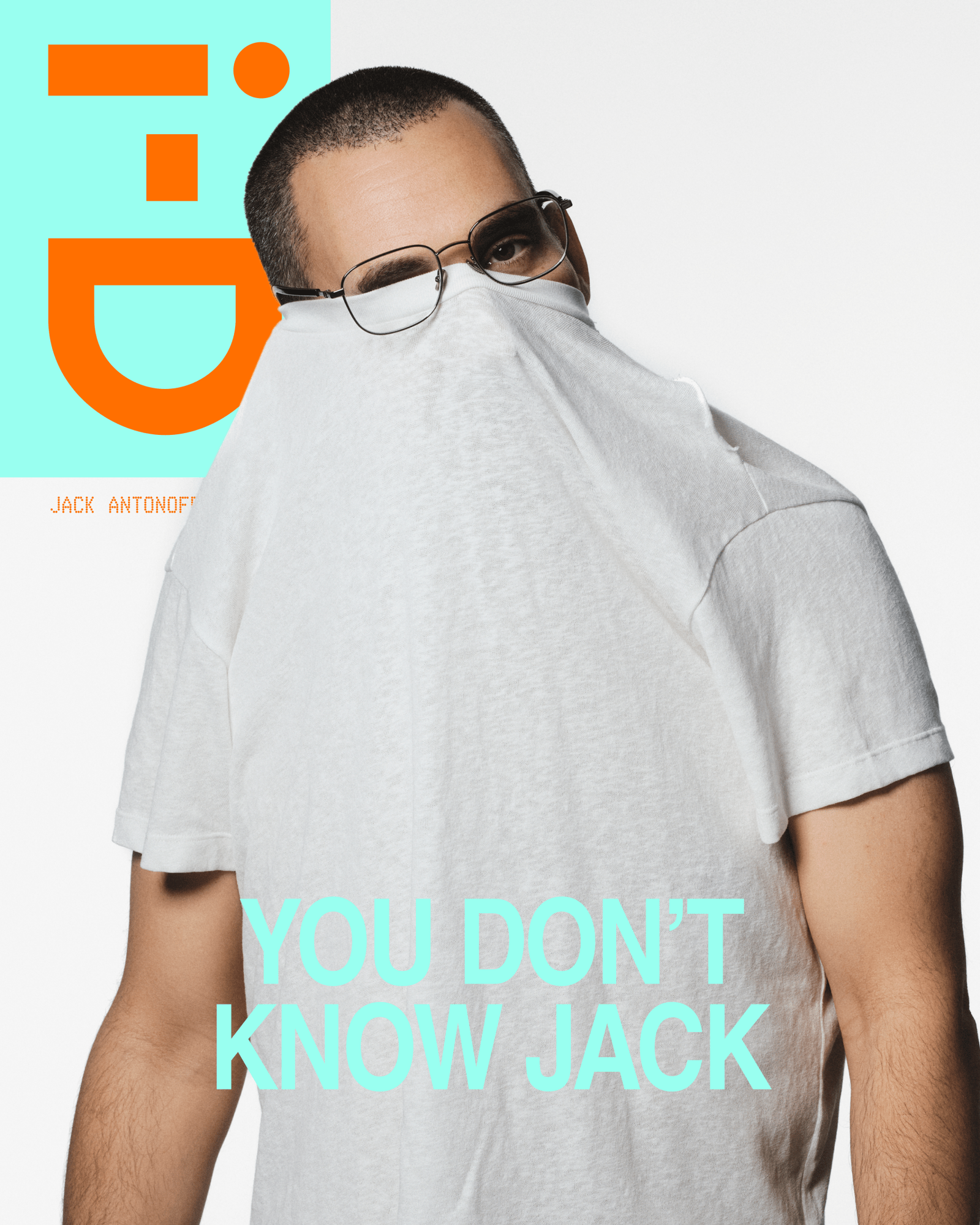

in the lead image: sweater HERMÈS; top CARTER YOUNG; jeans and glasses JACK’S OWN

groomer HIDE SUZUKI

set design CATHERINE PEARSON at JONES MGMT

photography assistant ZACH HELPER

styling assistant DAVIEL CASTAÑEDA

production THE MORRISON GROUP

location SPLASHLIGHT STUDIOS