After months of back and forth on Facebook, Ajamu X and I first came digitally face-to-face via an intergenerational panel about sex and cruising in the digital era. There, the Black queer photographer spoke with unbridled passion about pleasure as activism, the potential for our bodies to be spaces of limitless exploration, and the importance of exploring technologies of the self to uncover such possibilities. Ajamu’s words then made me think about the body as an archive, of Black gay men’s bodies as sites of experience, exploration, fun and history.

Originally from Huddersfield, Ajamu has been making and curating art in this area for over three decades. When we sit down to speak, this time in a one-to-one setting, we’re discussing his upcoming project, the AJAMU : ARCHIVE, a limited edition fine art book which “unapologetically celebrates Black British queer bodies, desire, pleasure as activism, and difference”. Financed entirely through Kickstarter, its £15,000 target was hit within six days.

But Ajamu was confident he’d reach this target. “There are people around me who support me and have been part of my journey for the past 25-plus years,” he says. He’s wearing a Black T-shirt with the words “SEX PIGS” written in red, which he explains is taken from a 2002 Terrence Higgins Trust sexual health campaign educating gay men about syphilis while refusing to sanitise the discourses around sexual health. “I will send you the material from this amazing campaign”, he tells me, “I like when our people reclaim words that people might find problematic. SEX PIGS. It speaks to me.”

As well as his body, which he explores in self-portraits, Ajamu’s clothes are an archive, as are the books and art objects and sex toys arranged on the shelves behind him on our Zoom call. With all that I could read and interpret of Ajamu by merely looking at him and his background on camera, I became all the more fascinated to learn about AJAMU : ARCHIVE and its meanings, ideas, and evocations of memory. And so our conversation became a space for intergenerational knowledge-generation, as I was myself challenged with fresh perceptions of how to interpret art, photography, and the figure of a Black man’s body.

Hi Ajamu, how have you been?

I’ve been fine, babes. Just getting on with projects and all that kind of stuff. You know, just busy, busy, busy.

So is the AJAMU : ARCHIVE meant to be a holistic collection of your life’s work so far?

I’m not sure about that. I think for me what it does is bring together some of my key pieces, including work that has not been seen. And the project is about the fact that artist books by Black British queer photographers do not exist, or they’re extremely rare. While my work has appeared in books and catalogues over the last 30 years plus, it’s been challenging to find people to publish the work. So I’ve gone back to what I used to do and self-published and brought aboard people who have been part of this journey for years. It’s interesting, when you contact gay publishers, and they say that your work is not the kind of gay work that they like. Because my work is not tied up with the body beautiful, and muscle boys, and white muscle boys, and Black muscle boys. A handful of the gay press said no, so I’m just going back to my punk attitude and saying, ‘Yeah, I’ll just do it.’

So your work is intentionally less beholden to queer mainstream ideas of the body beautiful?

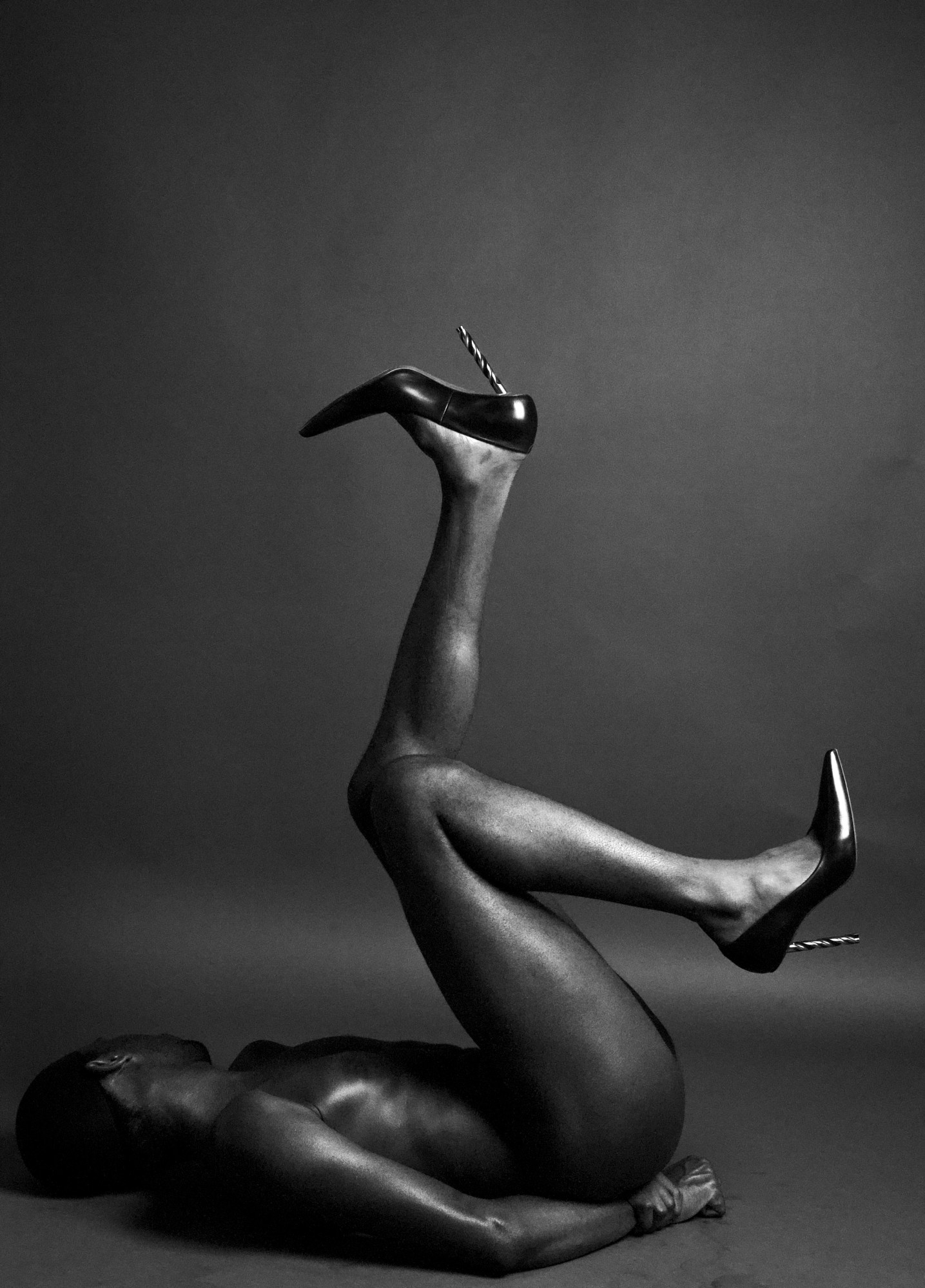

My work is more about the ideas that I want to engage in and around the Black male body, sexuality, pleasure and joy. It’s about presenting a different kind of politic. It’s not about those classical body types, it’s about creating work. And that also doesn’t start from a right-based narrative, or an oppression-based narrative. I always start from aspiration, celebration, pleasure as activism, erotica, and so on. So my starting point kind of pushes back against how I often see lots of Black queer work get automatically locked into oppression-based political ideas.

With that said, did the social-political context of the 80s motivate you in pursuing this kind of work, and has your work ever been in response to that zeitgeist?

My starting point is, as it’s always been, as an isolated Black gay man, coming from a small town. What were the kind of images I needed to see? Obviously while the social and culture context is important, I’m resistant to always placing the work in that context, as if the only the way to look at Black and queer experience is through that social-political public lens. For me, a larger context is that I think we live in a country that has a fear of the erotic, a fear of pleasure, so that’s where I start from. And so over the years, my work has been about how we talk about fantasies, and pleasure, in other kinds of ways. Whether it’s kink, and so on. And so really I don’t start from that social-political place, because it’s not always that interesting for me.

You’ve done some mainstream work as of recent – the show Me and My Penis on Channel 4. Do you envision yourself ever bringing more of your work on to mainstream, commercial channels?

I prefer niche art spaces. There is an obsession with the mainstream. And there’s also a Black mainstream and a queer mainstream. So I think you have to be clear about which mainstream you’re talking about. My work is not for everybody anyway, not even all Black queers. And I think there is a danger to thinking that if you’re mainstream your work has more value. My work already has value, mainstream or not.

You’ve previously said that you don’t want your photography to be reduced to the politics of representation and identity. What do you feel is the correct way for people to receive your work, and can there even be a ‘correct’ way to perceive the kind of work you do?

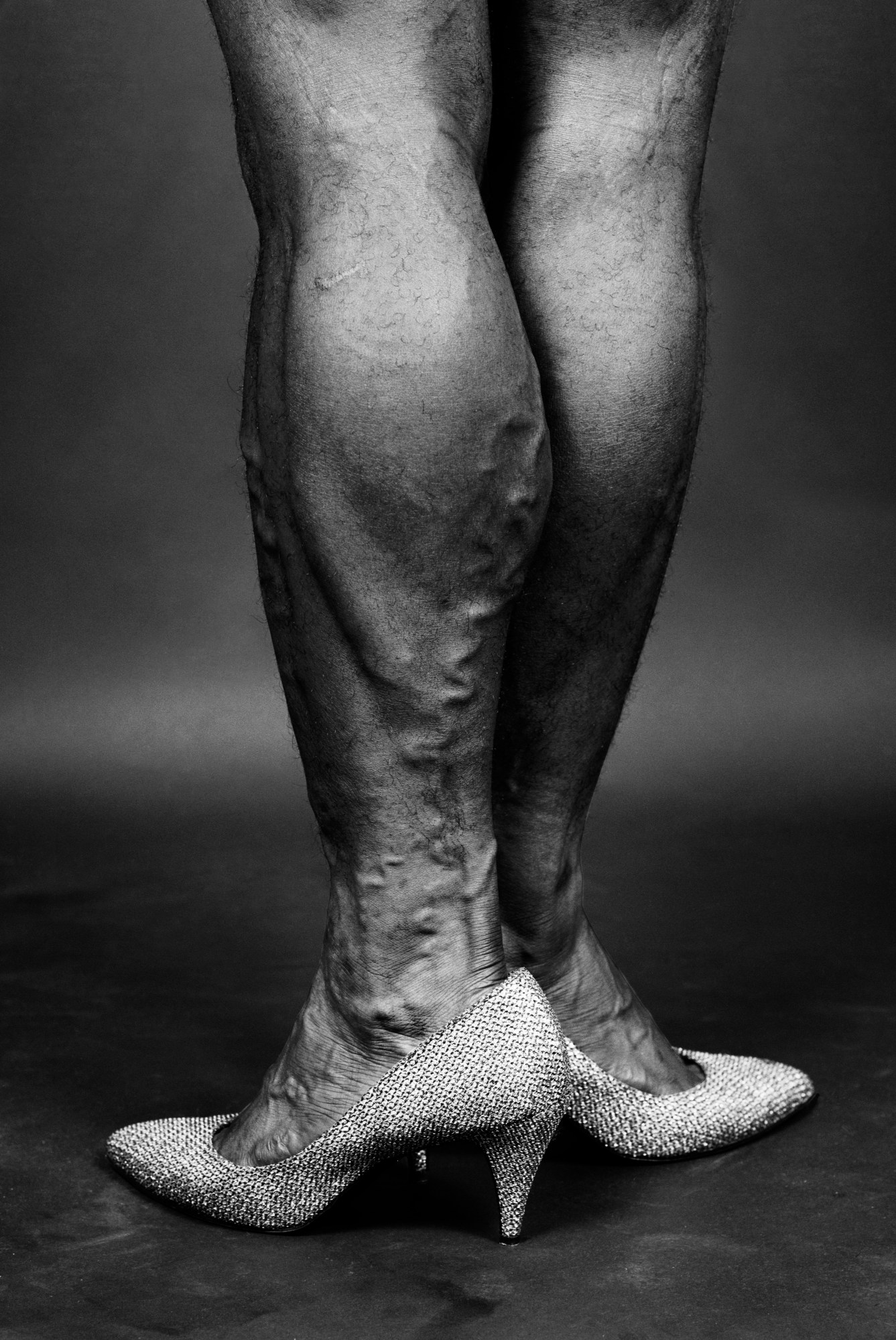

For me, there is no ‘correct way’ in terms of how people can view my work. What I’m saying is that there is a way in which Black work isn’t always looked at through the lens of its formulation. The photograph is also an artefact, an object. So we have to have dialogues around process, aesthetics, texture, scale, these things that are involved in the artistic process. My frustration is if you then only come into the work as a means for Black queer people to educate you on diversity and inclusion. Our work is far more complex than that. So I push back on this obsession with content and representation, not that it’s not important, but there are other kinds of conversations we need to have too.

So talk to me about the artistic process. The reward for the highest donation bracket in your fundraiser includes a special, limited edition of 30 copies of the book, case bound in black leather, with an embossed cover and a handmade and printed slipcase. What is the process behind that?

Leather and kink is part of my central experience, and I wanted some books, as part of that 500, which represent tactility, and touch, and smell. That’s really important as part of the sexual process as well. There are materials I want to work with as part of this process. The next project will be working with rubber, for instance.

So you want the materiality of the art you’ve produced to represent the kind of sex and scenes you’ve engaged with?

Yeah. The book is not separate from who I am. I am the book. So naturally, there’s a way to try and weave things in, and assign what is important to me. And I think what’s key is that this book will represent those ideas as passionate about texture and touch and materiality, and so really there’s other ways I want people to engage with the book. Not just the contents of the book, but the book itself.

All of your photography is in black-and-white. Why is it that you always work like this visually?

Black-and-white is not devoid of colour, in the sense that there are lots of different shades of black and white and greys in the print itself. There’s a tradition of early 20th century photographers, whose work I really love, [shot] in black-and-white.

Who are those early 20th century photographers?

Pierre Molinier. George Dureau. Diane Arbus. I love the richness and tones and how they’ve mastered light. And that’s where I look towards, those kinds of craftspeople.

What’s the process like for you when you stage your photography?

The process varies depending on the kind of work I’m doing. Unless I’m doing straightforward portraits, it’s about the kind of ideas that I want to work with. My home is my studio, as my darkroom is in my home as well. So really for me, the studio space is where I play around with ideas. My models are either very close friends or ex-lovers or fuck buddies. Basically, I don’t want to explain what I’m doing. I want people to just allow me to play around with ideas.

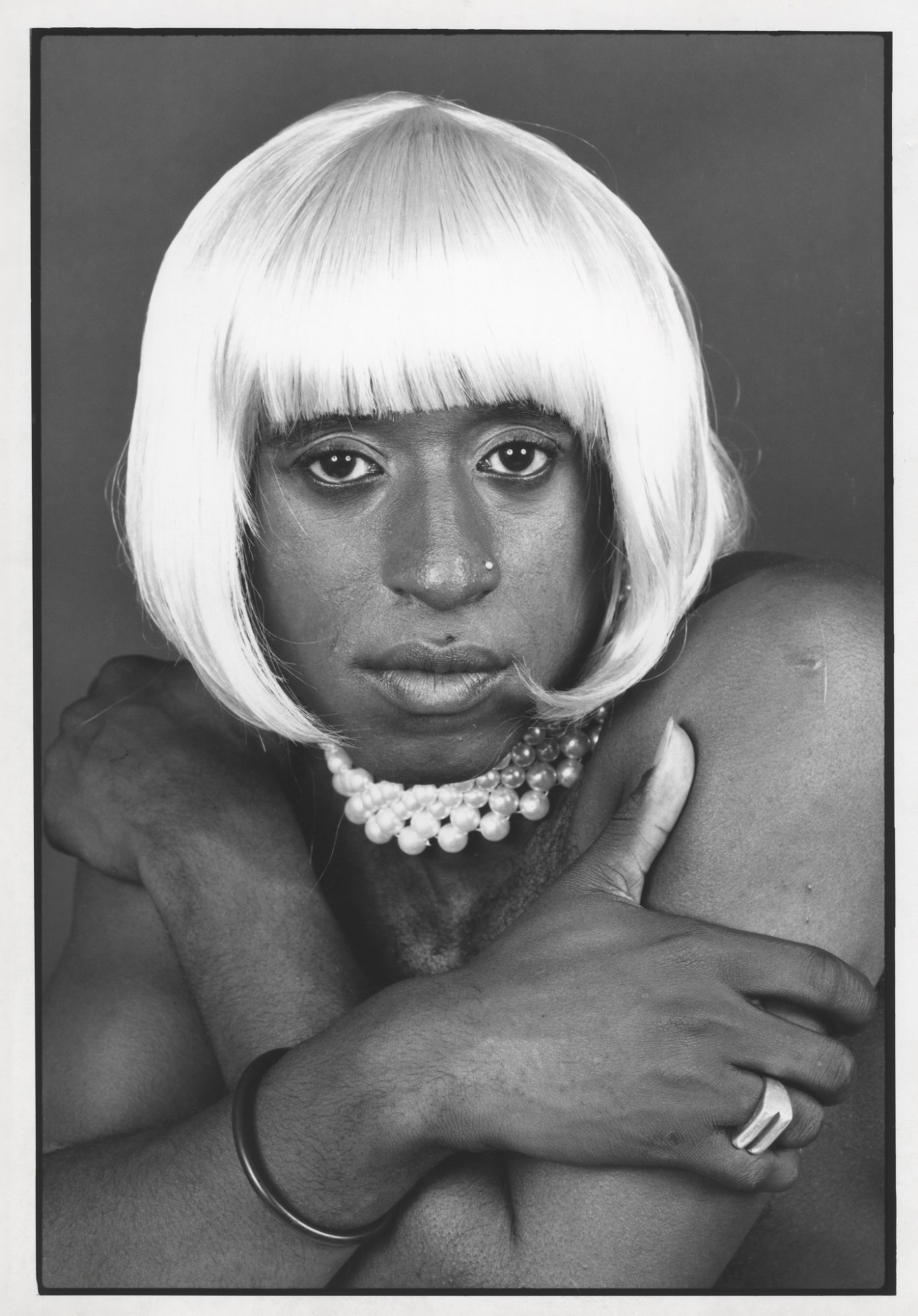

I’m looking at some of your older photographs. My favourite one here is the self-portrait in the blonde wig. What year did you take that in, and was this just another case of playful, spontaneous, creative direction?

The self-portrait in the blonde wig was 1993. The blonde wig has a lot of cultural significance — Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield — it’s invested with a specific meaning within western culture, you know, ‘blondes have more fun’, and so on. So I liked to play around with that and discuss this within the context of a Black body, playing around with drag performance. Some of these photographs I appear in because I can’t always find models to photograph, when ideas come to me at 12 o’clock at midnight, for instance. And so actually, I’m able to wake up, get props, shoot work, and then go back to sleep. Sometimes it’s about questioning and playing around with these binary ideas around male, female, Black, white, straight, gay.

And there’s this photograph, the ‘Circus Master’, where the model wears a harness, holds a whip and sits on a throne. Is the slave-master, power-submission dynamic a recurrent motif throughout your work?

I think that a lot of my early work drew upon those motifs because, whilst I’ve been out about my sexuality, myself and other Black queer folks have been marginalised around our sexual practices. There are still cultural taboos around certain kinds of pleasures. And because I am very out as someone who’s into kink, my work is always answering the question, What are the images I need to see? And then I go and create those images, whether it’s kink, whether it’s Black men kissing. And actually, we still don’t see a range of images around Black on Black men in the context of the UK, so my work is about filling in those gaps, with my interpretation of intimacy.

So you’re studying for a PhD at the moment?

Yes. I am doing my PhD at the Royal College of Art, part-time. And my research is rethinking the darkroom, the photographic darkroom, and the sex darkroom archives.

When will you finish your PhD, and will you be making people call you Dr. Ajamu?

I will complete it in 2023. People can call me Dr X. Dr. Ajamu. I have a range of names that people can call me.

And what are some of those other names that people call you?

Master Aab. That’s my kink name; it’s in homage to one of my Black queer heroes, Dirg Aaab-Richards. Daddy. Ajamu X Master. I have lots of names, depending on the context that I’m playing in.

Find out more about AJAMU : ARCHIVE here.

Credits

All images courtesy Ajamu X