2020 was a year that forced artists to adapt in many different ways; prepping online exhibitions, packing up studios, and facilitating Zoom visits to their creative spaces. For London-based Latvian artist Konstantin Zhukov (@hashtagzhukov), it was not just the pandemic but an unfolding political situation that called him home to Riga, Latvia.

In October 2020, he moved into a bright room in the city’s centre as nearby parliament repeatedly debated the country’s Civil Partnership Bill — only to vote against it. This was just the latest blow in an ongoing struggle for LGBTQ+ rights in Latvia, with parliament currently reviewing constitutional amendments proposed by the country’s far-right National Alliance to define family as a union exclusively between man and woman. These amendments would only further inhibit the progress of LGBTQ+ rights in the EU nation.

Against this unsettling backdrop, Konstantin set up his improvised studio and began a self-initiated research residency into Riga’s queer history. Within a month he opened his studio to the public, showing recent work and research. It was not only a way to touch base with his hometown — plugging into the city’s contemporary art scene and its increasingly vocal queer community — but a way to underline the importance of queer representation.

“The participants of the first Pride in Latvia, which took place in 2005, were met with aggression,” Konstantin says. “Then 10 years later, the Europride that took place in Riga saw some amazing numbers — 5000 attendees with no major incidents reported. However, the political powers are failing to reflect these changes in society.”

Inside the exhibition space, photo experiments and works-in-progress are intermingled with reference texts, archive images, and notes. There’s a sense of scrolling through the artist’s camera roll.

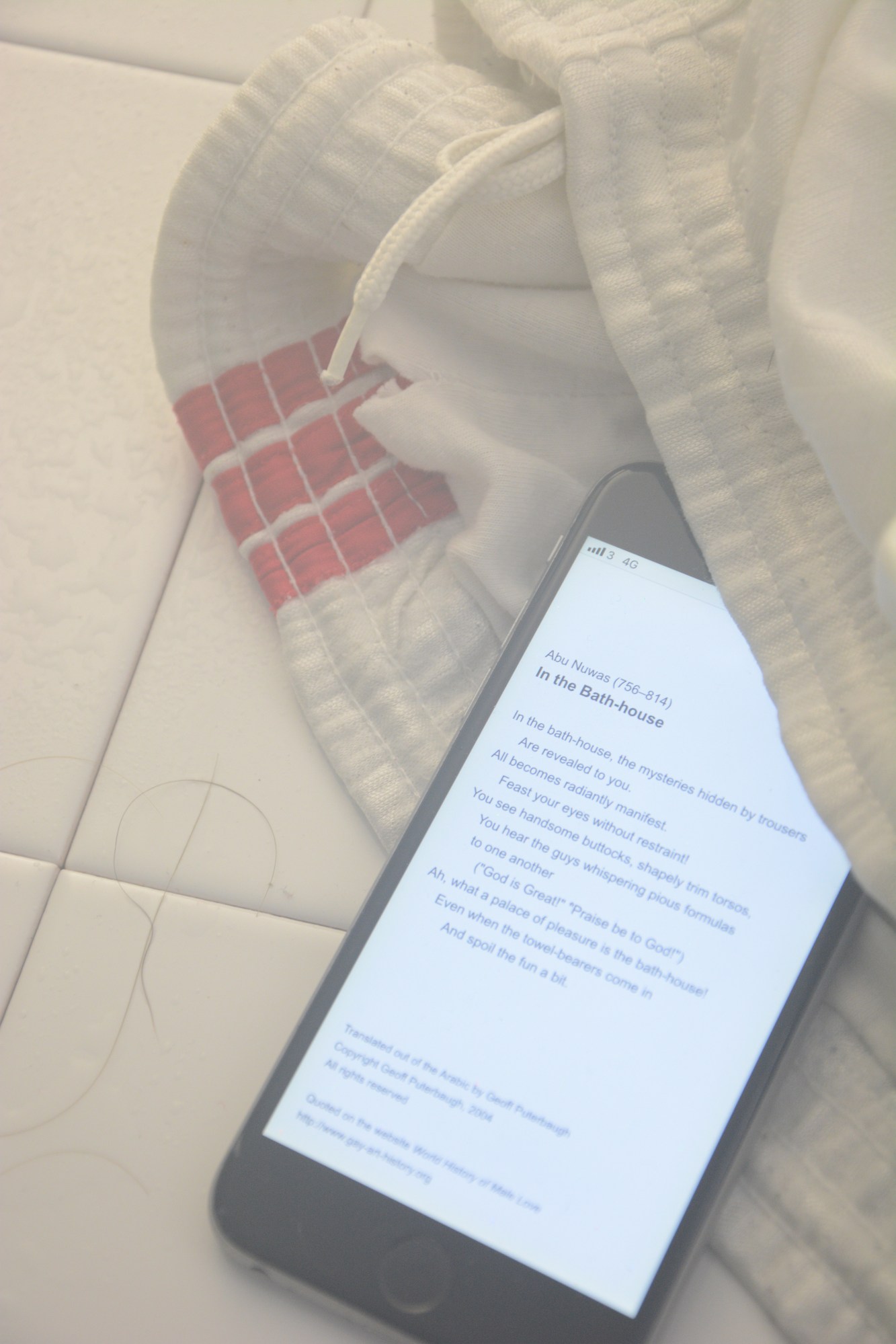

Konstantin reinterprets various queer histories through the lens of contemporary culture. His work is a mirror to his lived experience — as such, his work focuses on “moments of attachment, sex, and desire between men.” Homoerotic poems of the Islamic Golden Age, love letters written by Medieval Monks, and Michel Foucault’s work on sexuality sit alongside photographs of gay and queer men. “The highlight was when a straight man was modelling for one of my early works based on homoerotic poetry — it was so amazing to see that someone shares your ideas and vision and doesn’t pay that much attention to the label of sexuality. As my practice is growing, I acknowledge the fact that it has to become more diverse too.”

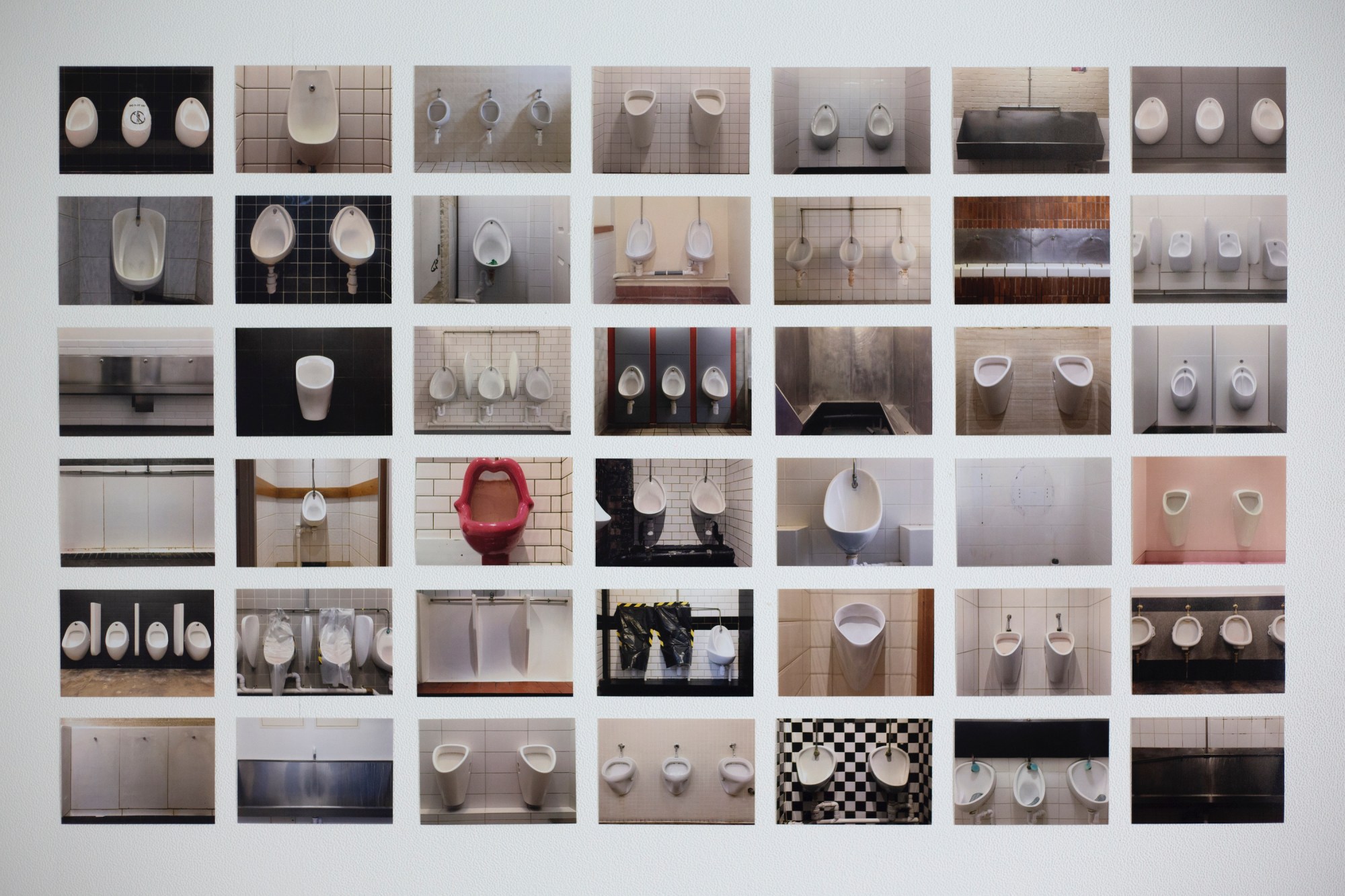

A central rail is draped with fleshy photos spun out in long rolls like analogue film, bringing to mind the draping of flags and the dramatic festoons of Renaissance painting. On another wall, his ‘Shy Bladder’ project presents a typological study of public urinals. Konstantin describes how “a lot of things are happening at urinals — a ballet of cruising in some and a contest of ‘masculinity’ in most.” Exhibited as a grid of 42 photos, the work is accompanied by quotes from the artist’s research into the pissoir past and present, drawing on a range of themes from fetish and history, to public sex and feminism.

Konstantin is interested in the histories that get forgotten, or deliberately swept under the rug, something that chimes with the contemporary experience of being queer in Riga. “LGBTQ+ visibility, or absence of it, is a big problem. Most gays live happy lives, but in a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ kind of way. You kind of don’t have a problem when you don’t actually see it. That was the way I grew up and lived before I moved to London.”

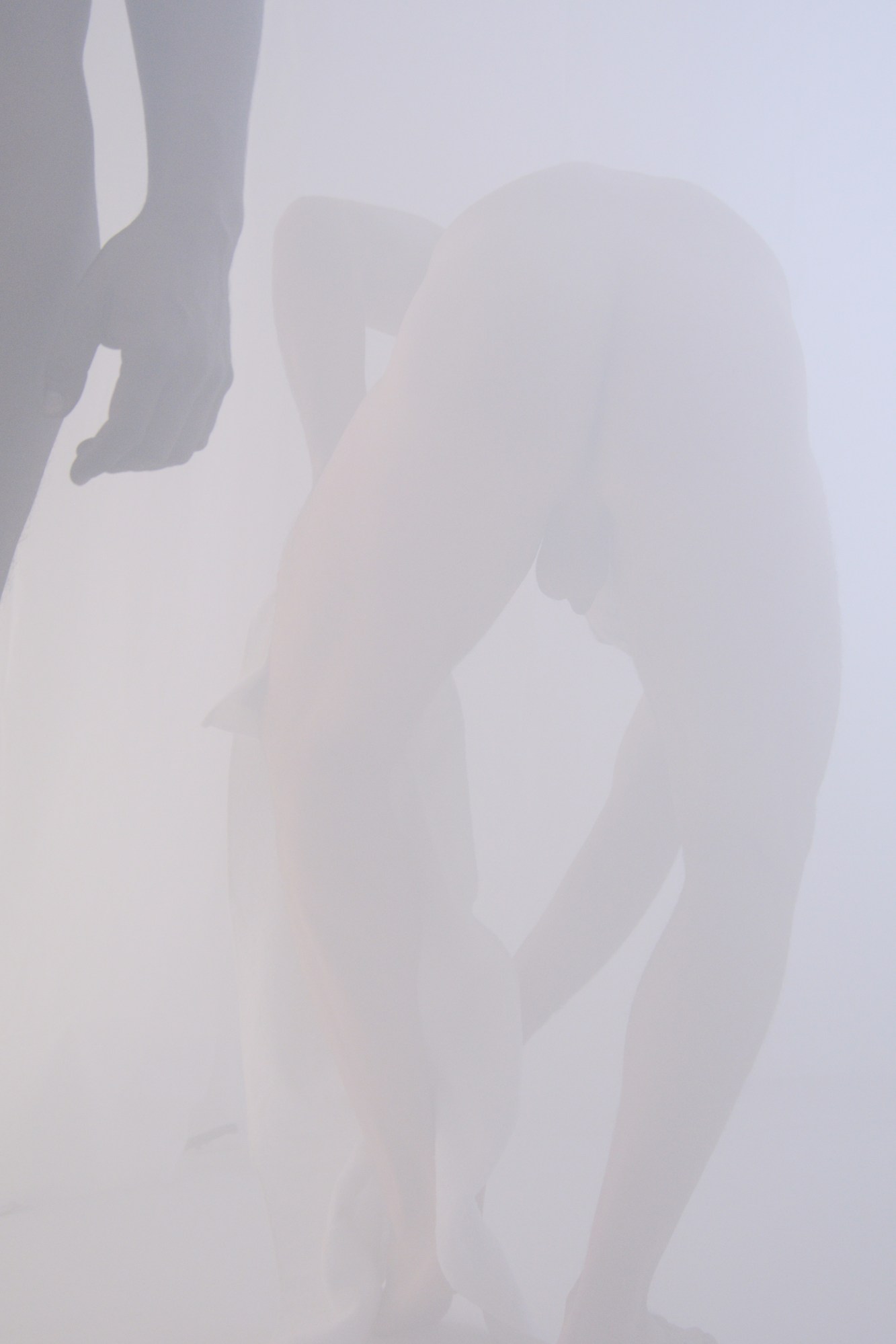

The Riga Open Studio’s centrepiece is a super-sized print from his series ‘In the bath-house’, in which a nude male body bends away from the viewer to wipe himself off whilst encased in steam. The series takes its title from a poem by the classical Arabic poet Abu Nuwas, who rose to fame in ninth-century Baghdad as the undisputed master of the ‘ghazal’, or ‘love lyric’. Informed by the poem, and its reference to “mysteries hidden by trousers”, Konstantin examines the homosocial and historical potency of the bath-house; from 9th century Baghdad and Victorian England, through to the cruising of 1970s New York and contemporary saunas of Soho.

It is this expansive view of homosexuality — one that crosses borders, languages, and time — that Konstantin’s work seeks to invoke. By bringing his work back to Riga, he hopes that this representation will not only start conversations around queer visibility but act as a moment of self-reflection. “We have to study our queer history,” he says. “We have to understand that the liberties that we enjoy today didn’t come from thin air — they are the result of the people who came before us going to demonstrations, petitioning, fighting.” Acknowledging the work of organisations like Mozaika, which organises Pride events in Baltic states, and Dzivesbiedri, which is pushing for the validation of same-sex marriages, Konstantin stresses the importance of celebrating queerness in Latvia. “And that’s why we really have to talk — to acknowledge their work, and continue this conversation.”

Credits

All images courtesy Konstantin Zhukov