‘Resilience’ is a word often associated with Beirut. Unfortunately, following the explosion at the city’s port on 4 August exactly four months ago, striking images of the Lebanon capital ingrained into our collective memory are that of a city in ruins. Images of people who lost everything in a matter of seconds and found themselves, once more, forced to tap into their so-called ‘resilience’ to pick up the pieces and start all over again.

What is less known, however, is that those same people were already drowning in an unprecedented economic collapse, a humanitarian crisis and an ongoing revolution — all while having to fight a ruthless, corrupt and criminal ruling class that has been blatantly oppressing and robbing its people. Before going down this dark road, of course, the country was still licking its wounds from the merciless 15-year-long civil war, which ended in 1990. Yet despite all of the above, a group of young local fashion designers, architects and photographers continue to believe wholeheartedly in Lebanon.

This scene of individuals has resolutely decided to stick around, to reclaim their own city, even though everything — lack of support from the government, a broken political system, the absence of social justice — is pushing them to leave. Armed with their talent, they’ve built a creative hub in the area opposite the Port of Beirut, precisely where the blast happened and where many creatives once had studios. With limited resources, in just a few months they’ve succeeded in ensuring Beirut remains a vibrant hive of arts and culture.

Many of these young creatives were injured in the explosion, had their studios destroyed and saw their dreams crushed. And while some were forced to leave Lebanon altogether, the talent and drive from those who remain is stronger than ever.

Here are 11 creatives who played a crucial role in putting Beirut on the global fashion map, and who continue to rebuild the city’s creative legacy.

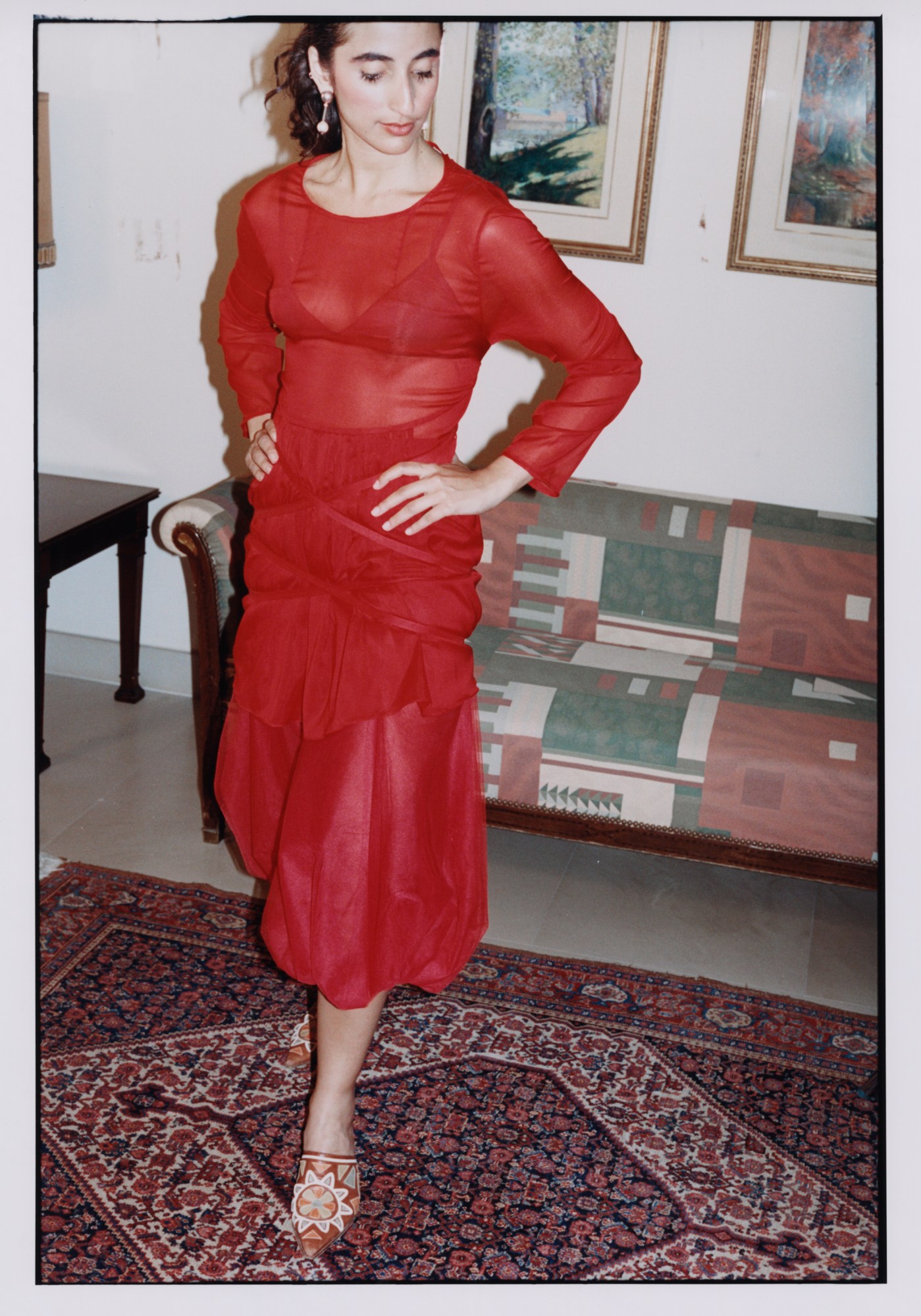

Cynthia Merhej, fashion designer at Renaissance Renaissance

After her studies in London, at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art, Cynthia Merhej decided to return to the fold where she first started exploring the extent of her talents: illustration, DJing, and photography. But deep inside, she had always known that she wanted to create clothes. She got her sharp eye for design and her deep appreciation for clothing “thanks to my first-hand experience, next to my mom who runs a couture and prêt-à-porter business”.

In 2016, Cynthia took a leap of faith and launched her first collection in Beirut under the label Renaissance Renaissance. A name that summarises what the brand stands for: a deep dive into the history of garments. “I like to refer to it as an exploration on identity, a way to play with codes of gender and most importantly a reflection on what it is to be a woman,” she explains. Indeed, the Renaissance Renaissance woman seems to have leapt off the page of a Brontë novel, only to reinvent herself in the present day and dismantle gender boundaries. This blurring of identities and eras caught the attention of Net-a-Porter where Cynthia is currently showcasing and selling her AW20 collection.

As for the future, though the 31-year-old designer has temporarily relocated to Paris, she still produces her clothes in Beirut. “This is my small contribution to the local ecosystem,” she says. “We should not fool ourselves. Given the disastrous situation our ruling class has thrown us into, it has become impossible for any business to plan, work normally, import, let alone grow in these conditions.”

Sarah Hermez, Caroline Simonelli, George Rouhana and Tracy Moussi, co-founders of Creative Space Beirut

Due to a lack of government support and the expensive education associated with the field, pursuing a career in fashion in Lebanon was long considered intimidating. Thankfully, Creative Space Beirut came to the rescue. The project was conceptualised in 2011 by Sarah Hermez, a Parsons graduate who returned to her hometown and realised that “so much had to be done”.

With the guidance of her mentor, Caroline Simonelli, and with zero financial aid, she launched a tuition-free fashion school out of a Beirut basement. Their three-year intensive curriculum combines technical courses, theoretical classes and experimental learnings. “Some of our students never went to school but they all had an immense talent, despite their lack of background in fashion,” Sarah adds.

The initiative developed further over time — Sarah joined forces with Tracy Moussi and George Rouhana — and after years of moving between basements and apartments, the team finally settled in the Beirut Souks. “As our mission became greater than us,” they explain, “Creative Space Beirut grew into a multifaceted social enterprise providing resources for the innovation of design practices in the region”.

It now encompasses the School of Design and its annual graduate fashion show, the CSB label and an online retail platform. In retrospect, this crucial enterprise didn’t just nurture designers that otherwise would’ve never realised their talents, it also raised awareness for supporting local businesses — the kind “that were usually looked down upon by a clientele who prefer shopping abroad”.

Hit hard by the economic collapse, the pandemic and the 4 August blast, Creative Space Beirut is still picking up the pieces. “We were in the middle of a photoshoot when our space exploded,” says Sarah Hermez, who is currently moving the business to a new location in the Monnot neighbourhood. “We’re still aiming at our same dream,” she says, “that of building a big campus that would eventually include other schools, such as visual arts and architecture. What we’re doing is now more important than ever. As long we’re a united and rooted community (and with the help of our donors, the Drosos Foundation) nothing can stop us.”

Rym Beydoun, fashion designer at Super Yaya

Rym Beydoun was born and raised in the Ivory Coast before moving to Lebanon at the age of 10, where she was based until the blast on 4 August. After graduating from Central Saint Martins, the designer launched her brand Super Yaya, as “a cultural bridge, a way to bring together Beirut and Abidjan; to sew the edges of both cities in a visual way”. To create her personal aesthetic — a blend of those two worlds — Rym would get lost in African fabric markets, go digging through old family albums and pair her findings with archival material from Abidjan and Beirut.

In her Beirut atelier, the city instilled Rym with a “persistence in lightness. It set the tone and rhythm as it was the way I was working — persistently and lightly”, she says. It was here that she would explore and reinvent those African fabrics through her own dye techniques, weaving and printing practices; creating fantastically patterned collections in dramatic cuts.

At the peak of her ascent in the industry, Rym Beydoun miraculously survived the 4 August blast, during which she was severely injured. “I don’t really know what’s next,” she tells us, “but we’re surely in a transition. We’ll either do other things, do things in a different way, or stop doing things… it’s too early to tell”.

Tala Hajjar and Rabih Kayrouz, co-founders of Starch Foundation

Back in 2008, when the design and fashion industry in Lebanon was still crawling, new graduates and aspiring designers were clueless about how to produce a collection, market it and bridge local and international markets. Seeking some sort of mentorship, those entering the scene began approaching fashion designer Rabih Kayrouz (of Maison Rabih Kayrouz, which exists between Paris, London and Beirut) with all these questions and more. That’s when Rabih, alongside his friend Tala Hajjar (recipient of the Young Creative Award from the British Council in 2011), decided it was “the ripe and right time” to create STARCH, a non-profit organisation to help launch emerging Lebanese designers.

Together, armed with little more than their expertise and a will to nurture Beirut’s talents, they formed a creative incubator from which 53 fashion designers, architects and photographers have graduated in the past 12 years — including Roni Hélou, Krikor Jabotian and Salim Azzam (winners of the Fashion Trust Arabia award). STARCH have showcased, at a very early stage, some of Lebanon’s most prominent young designers and have undoubtedly contributed to putting local talent on the map.

In the wake of the blast, Tala tells us that many of their designers have lost everything: their studios, their dreams and their confidence in their country. “They’re forced to start looking abroad,” she says, “instead of strengthening the local scene, which STARCH has been determined to do. There’s no leadership to look after them or even recognise their talent, and until justice is served, until we stop fearing for our lives, there’s unfortunately no room for hope.”

Ana Maria Samaha and Ramzi Tabiat, co-directors of LaFabrika

When Ana Maria Samaha founded LaFabrika in 2015, little did she know her factory would become a fundamental link in Lebanon’s fashion production chain. After working in the industry at Maison Rabih Kayrouz, Samaha launched her business “with the intention of helping young local talent gain a better visibility in the industry”, she says. In just five years, LaFabrika had become a creative hub for a whole generation of promising brands, such as Super Yaya, Renaissance Renaissance, Jeux de Mains and Roni Hélou.

In 2020, a year which Samaha describes as a “true test of resilience and flexibility to all Lebanese people”, Ramzi Tabiat joined the team. Together, the partners aim to transform their local factory into a fully-fledged international production house, one which will “support our local workforce and provide them with resources to ultimately collaborate with regional and international designers”, says Samaha. “Because hope is not an option today, it’s a necessity.”

Makram Bitar, stylist and image-maker

Not your average stylist, Makram Bitar is an irrefutable catalyst for change in how women are portrayed in the Lebanese press. Against all odds, the self-taught stylist decided to take everything Beirut had to give and channel it through his very own otherworldly lens. His work transcends the horizons of fashion, instead depicting the emotional landscapes of the women and men he dresses, as though they were characters in a book.

As one of the first stylists to introduce streetcasting to Beirut, Makram has not only disrupted the visual codes of glossy, conventional editorials, but also managed to forge creative links internationally. “It was a struggle to find my voice in an environment that was kind of static,” he says. That said, though working closely with local brands, Makram has also collaborated with photographers Esther Theaker, Joyce NG, Senta Simond and Alice Neale, shooting for Marfa Journal, Buffalo Zine, Rimowa and Kenzo.

“Even though I had always planned to establish myself abroad,” he says, “I’m doing so today with a bitter feeling; that of being kicked out of my own country because of the mafia that has been shamelessly ruling us.”

Salim Azzam, fashion designer

Salim Azzam was raised in the village of Bater-Al Chouf where traditions and crafts such as embroidery, crochet and point-de-croix were struggling to survive. “Fashion was never seen as an option for me though,” Salim says. “It was simply not conceivable for boys”. But after studying Graphic Design in Canada, Azzam returned to Lebanon with a very clear purpose in mind: “make my community proud, celebrate and modernise its crafts.” And so the designer headed straight to the STARCH foundation, where Rabih Kayrouz took him under his wing.

In 2019, Salim won the Fashion Trust Arabia Award for his ready-to-wear collection, which helped his brand take off and allowed him to establish a workshop in his hometown. Out of this cocoon, nestled in the mountains of the Chouf, “where everything is done from scratch by 35 local craftswomen”, Azzam has been expanding a label that acts like a vessel through which old crafts are preserved and reinvented.

“This year, I feel that I’ve been abruptly stopped as I was setting the foundations of my career,” he says. “Sadly, my country is forcing me, like many other designers, to have one foot overseas in order to sustain our businesses. But I’m only taking this step in order to help my small community survive in Lebanon.”