There’s something irresistible about melancholy. In the ancient world, the melancholic was thought to suffer from an excess of black bile. Aristotle believed just the right amount of melancholy could act as a passionate, energetic force. Rappers, the preeminent representatives of poetry in the mainstream, know this only too well. They immerse themselves in pathos, dripping with the tragic alienation of having made it, and — often unlike many of their peers — having lived to tell the tale. They seek a crown they will spend the rest of their lives guarding. Melancholy is a trailing feather boa. Wrap it around yourself and bask in the theatrics of your sadness. Mope around your luxury penthouse.

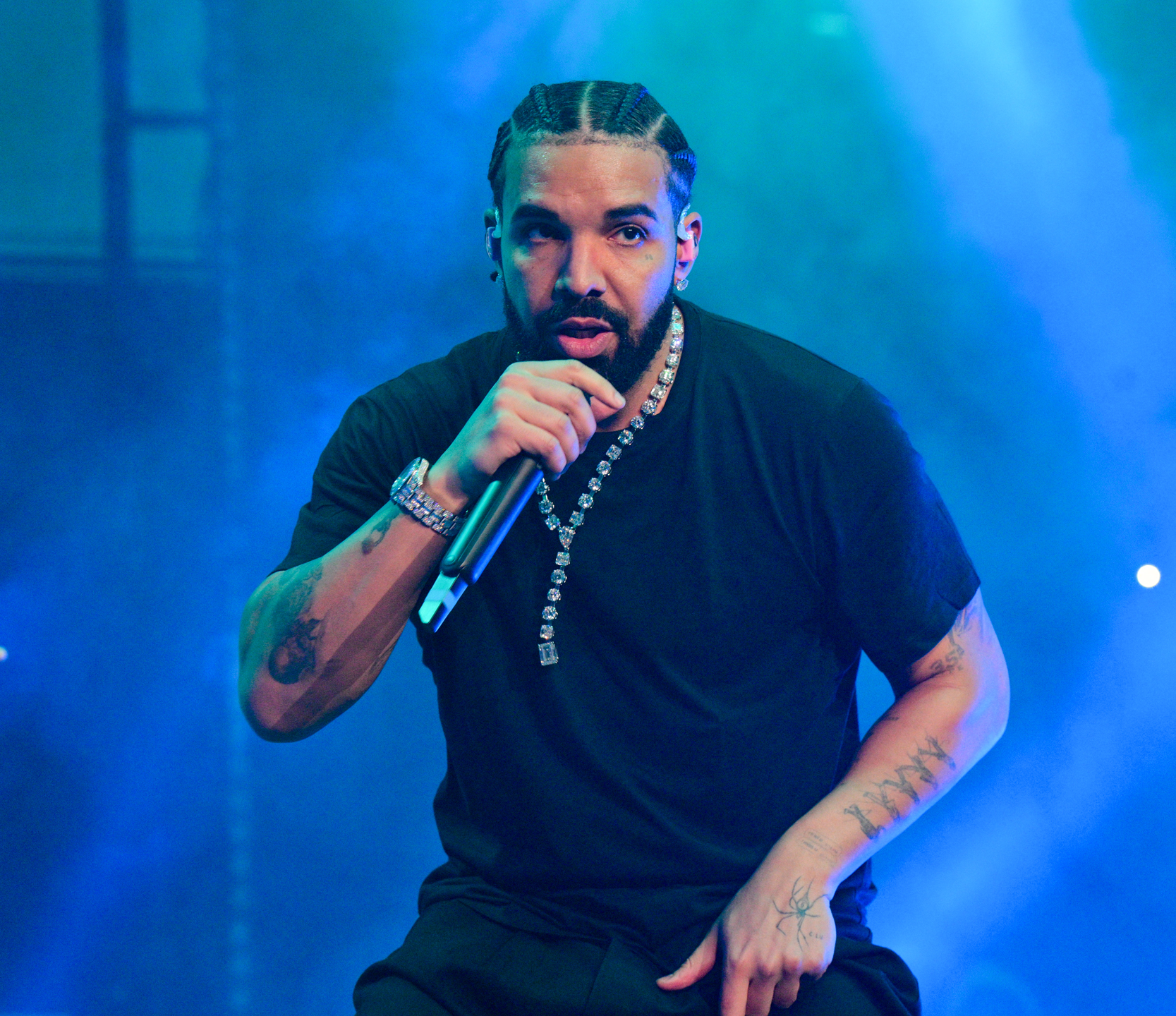

Despite his suburban upbringing, no modern artist embodies this state of opulent melancholia more than Drake, Toronto’s very own laureate of lavish longing. His latest project, Titles Ruin Everything, is a debut collection of bite-sized poetry, a collaboration with the songwriter Kenza Samir which is nevertheless saturated with the rapper and singer’s signature – a bashful malice. “I actually do have good things to say about you / just not this book,” he writes, peeping from under his long lashes. From the book’s first pages, there’s a sense of lethargic petulance. It’s frustratingly relatable, and it’s why Drake remains the bard of pointed Instagram captions: those targeted grenades we lob at the specific person we’re pretending to ignore. “Swimming in regrets / is not cardio,” one poem reads, practically begging to be lifted off the page. “Charged it to the game / and paid the bill.”

Puns land unevenly, but some are at least deserving of a finger-snap at a poetry slam. The blank page is a playground for Drake’s indulgences. He wallows in the melodramas of the rich, famous and perpetually commitment-avoidant, a world “more liquid than solid”. As a reader, you alternate between rolling your eyes and being struck with a shiver of mirthful recognition. Drake can do what he wants, because he’s a superstar. Poets can do the same precisely because they’re not. Both share in the freedom of being unfathomable. (“Irony: It cost a lot of $ to feel free”).

Perhaps Drake has always been a poet. His verses are potent capsules of distilled emotion, little shots of concentrated relatability that his fans relive again and again. “I am the soundtrack for lives / that go on without me”, to invoke a couplet from Titles Ruin Everything. Like all poets, Drake has been accused of being relentlessly corny. The first poems we write are usually excessive, treacly, and overwrought. They may also be our most honest. “What is the difference between going through your phone & going through hell? / I can’t really tell”, reads one poem, recalling scratched out lines in a closely held journal. In another, he sounds like Wendy Cope filtered through Ambien and petty resignation: “Hearts break as much as they beat / a lesson I know too well, but hate to teach.”

In Titles Ruin Everything, the addressee is an ambiguous figure, a “you” that is as likely to be an ex-lover as it is an opp. Drake’s musings hover between the celebratory and the playfully bitter. His speaker is needling, regretful over the “acres” of distance he’s forced to erect between him and hangers-on, demanding women, and fake friends. Disgust flickers, at those who offer unsolicited advice even while being incapable of imagining the kind of life he leads. “Their insecurities are the main reason why I increase my security.” Such lines mimic the underdog’s anxieties, a staple symbol in hip-hop’s grand narrative. But Drake’s angle has always been cheekier, irreverent yet still possessed with that same twitching paranoia of the survivor. It may not have taken much to survive a comfortable middle class childhood, but a flayed heart can be its own catastrophe. Betrayal is the ultimate equaliser. If Drake can indulge in his wounds, or his worst behaviour, then so can we. The Canadian writer George Bowering viewed the poem’s line as a “dog trot”, following its own pace, “a tongue with a human mind for a leash.” Titles Ruin Everything opens with a dedication to “all the dogs”, teasing an upcoming album titled “For All the Dogs”. It’s for the despondent too, hunched over and howling.

A step between glamour and half-hearted grit, Titles Ruin Everything won’t surprise you, continuing the trend of recent poetry books by popular musicians, like Lana Del Rey’s Violet Bent Backwards over the Grass. For these artists, these collections are vanity projects. For their readers, they can often function as vanity mirrors. Drake’s book is a tepid document of contemporary malaise, an ode to being skeptical of the game but playing it anyway (and excelling at it). Melancholia is his domain, his kingdom of ashes and aphorisms. A wet maple leaf crushed underfoot. That’s Drake, the observer, the maddening shapeshifter. Chronicler of modern bros and their modern woes. This collection further proves how Drake’s talent lies in his ability to both disappoint and disarm in the span of a few lines. Poetry is the last refuge of the prematurely jaded, and it’s for this reason that his verses are one of the more bearable celebrity cracks at published poetry. If that isn’t saying much, then take it for what it purports to be: a stream of consciousness that may just, exasperatingly, mirror your own.

Titles Ruin Everything was published by Phaidon and is out now