Cecilie Bahnsen’s clothes have always conveyed an eerie, celestial romance — sure, they’re eminently wearable in the here and now, but there’s something about them that makes them feel as if they’d been plucked from Narnia. With its parade of sculptural, airy dresses — balloon-sleeved and in hues of ivory, earthen brown, sky blue and black — her AW20 collection, shown in Copenhagen back in January, was no exception. “When I was designing the collection, I was thinking of a faraway place; mysterious and dreamy yet earthy and exposed to the elements,” she says.

While she may not have been able to physically transport her audience there, she did so through the set, projecting a bleakly sublime image of a frozen landscape onto a lightbox. It conjured feelings of emotional barrenness as readily as it did ones of poetic escapism, and was taken by Swedish photographer and filmmaker Martina Hoogland-Ivanow on the tundra of northernmost Russia.

Cecilie’s relationship with Martina’s photography extends back much further than their AW20 collaboration, though it wasn’t until recently that she realised just how far. “The first photo series by Martina Hoogland Ivanow I remember seeing was for AnOther Spring/Summer 2006, art directed by Alexander McQueen and styled by Katy England. The shoot was dark and mysterious with a magical touch of childhood innocence,” she recalls. “A year or so ago, I picked up a book of hers, Circular Wait, then remembered seeing her fashion work in Dazed and AnOther Magazine years ago. In a sense, I discovered her before I discovered her. I had images by Martina on my mood board without even knowing her name, and the more I connected with her images, the more I realised these were the same images I cut out and admired as a young design student.”

For the textures and colours of her AW20 collection, she drew inspiration from Martina’s “photos of cold beautiful Nordic landscapes”, taken in remote locations from Tierra del Fuego in Argentina and the Kola Peninsula of Russian Lapland — settings that suggested “remoteness […], something unfamiliar and slightly disturbing,” she says. It was only fitting, then, that she enlisted the photographer to shoot the collection’s campaign, revealed exclusively here on i-D.

Cecilie, “curious to see [Martina’s] interpretation of my design and universe,” gave her free creative rein over the shoot. “We have elements in our work that we both like to be working with, such as layering, storytelling and the composition of groups of girls. These elements combined with Martina’s emotional and eerie aesthetic became the starting point for the shoot,” she says.

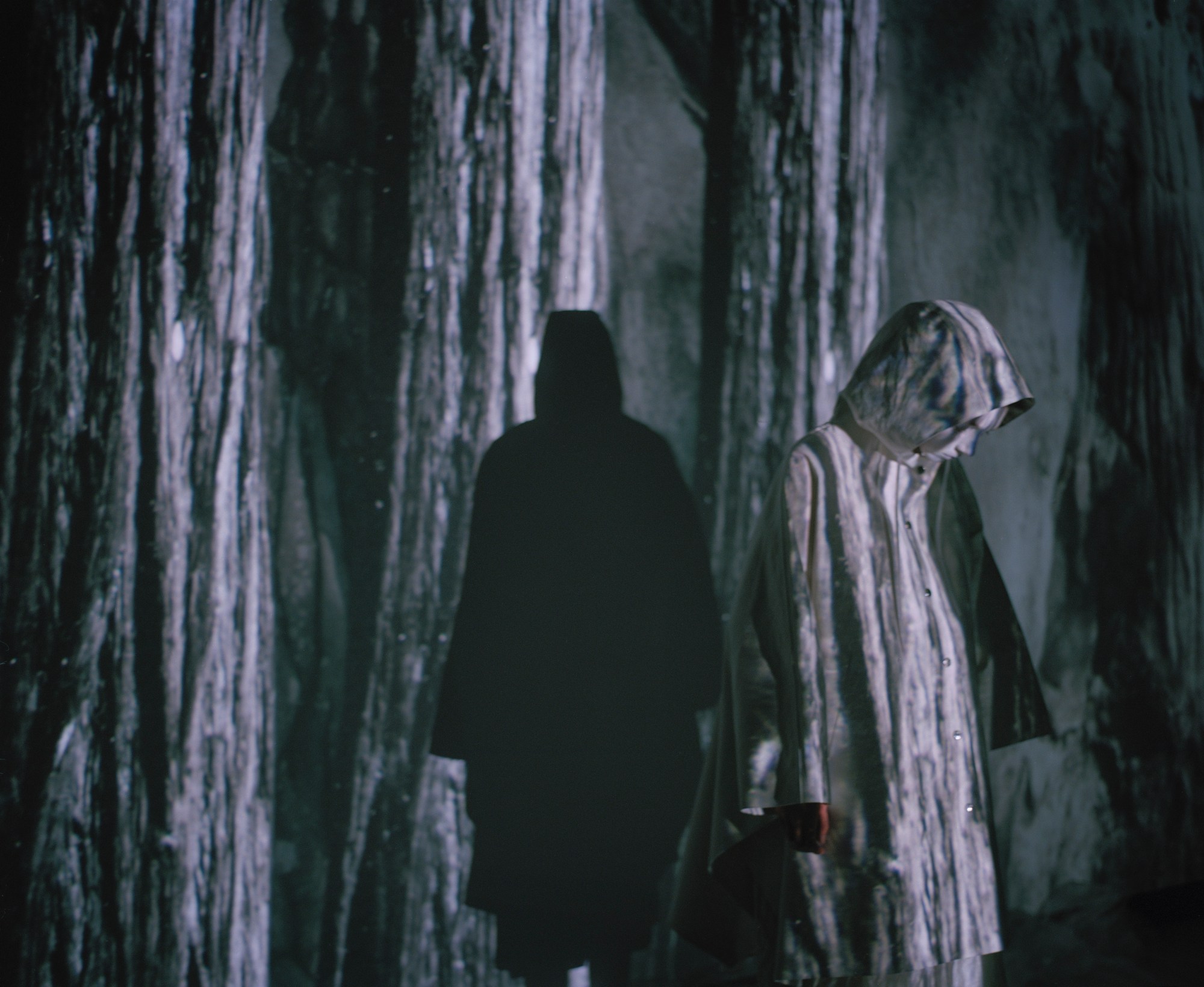

“The original plan was to make an exhibition or an art project,” the photographer explains, though the current global situation put a spanner in the works there. Instead, the garments were sent to Stockholm and captured in a shoot inspired by “an editorial shoot for AnOther Magazine in 2012 with Cathy Edwards and Martin Bergström, where I worked with a sort of kaleidoscope of different projected patterns.” Projecting landscape images onto a group of girls wearing Cecilie’s ethereal dresses, “the intention was to use the unifying element of Bahnsen’s design and find a visual method to camouflage the space between the figurative groups placed in the landscapes or various textures from natural elements, as well as merging the background and foreground into the same level of representation”. The resulting images are quietly haunting, yet rich with raw beauty, like cinematic stills of a coven meeting under a full moon.

“Both our worlds capture a kind of emotional Nordic mood,” says Cecilie, pondering the common ground the two creatives’ work shares. “When we create a look or a picture, we are both drawn to working with laying when conveying character and beauty. It is cinematic, dreamy, feminine and otherworldly.” It’s a sentiment that Martina echoes, despite the fact that the two have only met in the flesh once, at Cecilie’s January show. “I would put it down to the integrity and a very specific point of view that we both put across in our work,” she says. “I enjoy and sense the connection in the unity of the design and see that as a political or perhaps even a spiritual statement.”