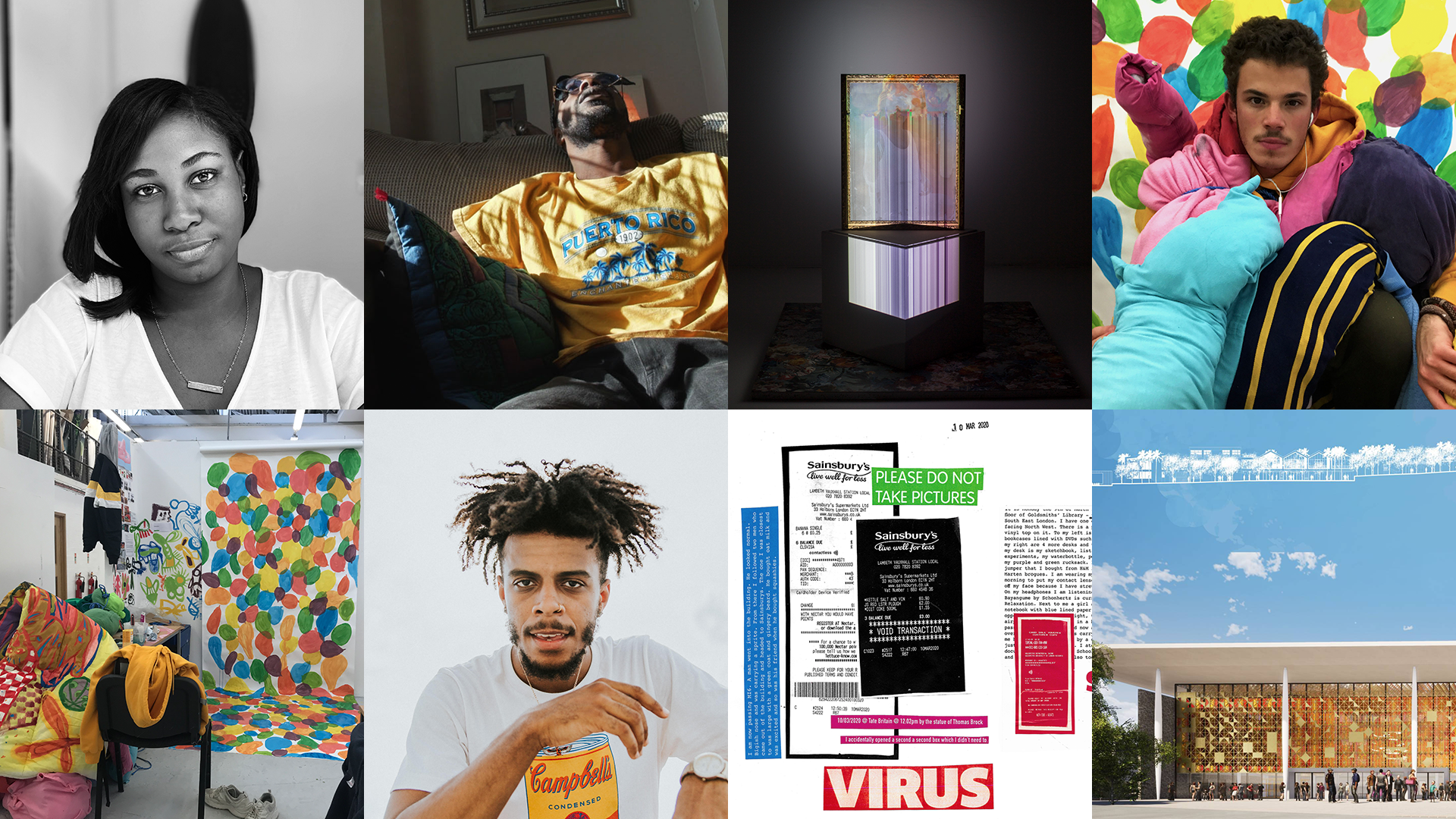

We’ve had over four thousand entries to the first ever online Global Design Graduate Show — where i-D teamed up with ARTSTHREAD to give students in the class of 2020 from all art and design courses the opportunity to showcase their work. Voting is now open, so we thought we’d introduce you to some of the entrants from a range of categories, from digital art to service design. Take a look at the work of David AJ Dunnington from the USA, Rachel Orphan from the UK, Rodrigo Costa from Portugal, Shanique Brown from Jamaica and Romana Halgošová from Slovakia, and discover the challenges they faced completing their final projects at home.

David AJ Dunnington, BFA, University of the Arts Philadelphia, USA

Where are you? Describe your workspace.

My workspace is Philadelphia. The environment here is so visually dynamic that whether it’s an empty lot, my roof deck or in Italian market, it’s hard not to find inspiration or create production value. It can be nerve racking when filming passionate scenes, such as a shouting match, in public spaces. Fortunately, people yelling at any point of the day is considered normal here. Bystanders wouldn’t really react much, they just stare, which I don’t mind, all things considered.

What is the name, theme, concept and final outcome of your graduate project?

The film is called The People Around You, it follows four men in their early 20s and the destruction of their friendship. Thematically it’s about how toxic masculinity can keep American men from having genuine relationships with their friends. I wanted to utilize surrealism with realism in the same way a show like Atlanta or Random Acts of Flyness would. The film goes from coded monologue scenes with dramatic lighting to naturalistic interactions with improvised dialogue, using actors that are friends in real life. I did a lot of shooting in the semester prior to the pandemic, so most of it was done; all that was left to shoot was the ending.

How has online learning changed your work?

It’s given me a lot of time to edit and fine tune things but I’ve just been stuck on the ending, mostly because I didn’t know how to safely go about shooting it during the pandemic. Film is such a collaborative medium and it is almost impossible to make something of substance without a crew. But I’m working on setting up a SAFE shoot to wrap things up.

What’s one thing that has helped you get through the past few months

The ability to talk to my friends, family and professors via FaceTime or Zoom while being apart. I can’t imagine going through this in a time where that wouldn’t be possible.

What are the most positive learning outcomes from this process?

I learned that you and your work will grow through hard times. I was able to persevere through something like this and still get my degree with a film that I was proud of.

What are the challenges of showing your work online?

Showing unfinished work is always a nightmare for any artist but thankfully my film was in a place where it could stand on its own as a “proof of concept.” But I was definitely disappointed that me and my fellow film students couldn’t present our films in the big auditorium on campus. It’s the night you anticipate all four years at the school, getting to show your work in front of staff, friends and family on a big screen. I don’t mind uploading my work but presenting it the way it was intended would’ve been more satisfying.

What are your hopes for the future?

I’m hopeful that me and my former classmates will be able to create finished products that we are proud of and that we get to a point in the near future where it is safe to go out so I can continue making art with my friends. After I finish this film I plan on starting a film project with some of my current collaborators about consumerism and American suburbia. Despite everything, I’m excited for the future of creativity and cinema.

Rachel Orphan, BA (Hons) Design, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Where are you? Describe your work space.

I have moved from London to Salisbury to my parentss house and have set up my studio in their dining room.

What is the name, theme, concept and final outcome of your graduate project?

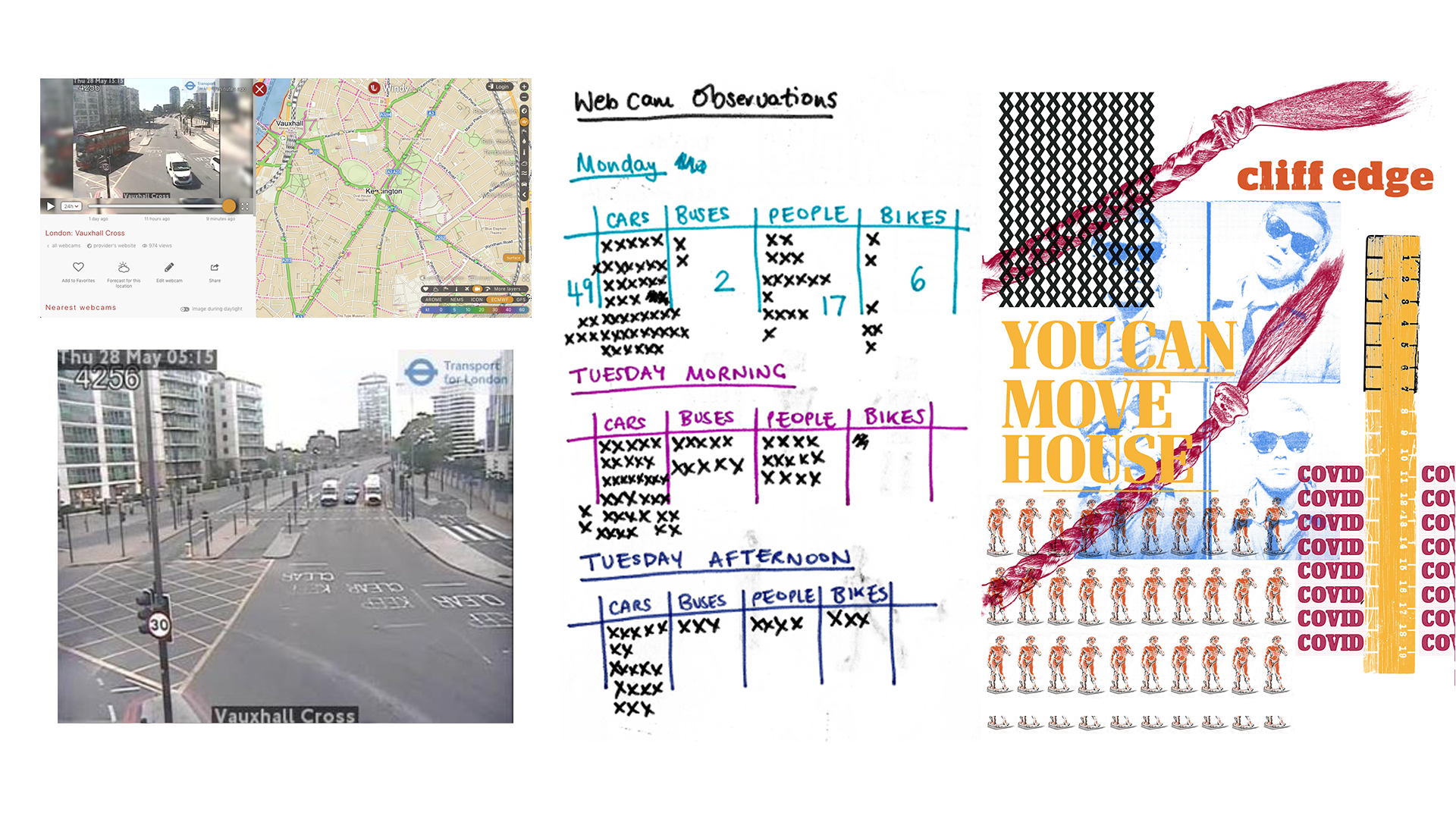

My project is called ‘Project Espionage: Designed to Deceive’. It is a designed investigation into the lives of spies in Vauxhall, London. That’s where MI5 and MI6 have their headquarters. There are a few different outcomes for my project. Firstly, there’s a collection of over 100 collaged posters that I have made during lockdown. Each one has data from Vauxhall encoded in it. I’ve also designed a zine, which has instructions for how to use CCTV cameras to create your own collaged poster.

Has the pandemic changed your graduate project? If so, how?

The main focus of my project is the two miles between MI5 and MI6 in Vauxhall, but I haven’t been able to visit that location physically since the beginning of March. I have had to adapt by watching the location via CCTV cameras. I wanted to work in a more analog and physical way this year so since the pandemic, I have had to adapt by introducing different processes such as weaving on a handmade loom.

What’s it like working without your university’s technical support? Have you had to innovate left to your own devices? I was making all of my collages using photocopiers and large scale printmaking techniques. I have had to adapt by making my own loom and using smaller scale printmaking techniques such as linocut printing. I am using my Dad’s scanner and printer lots too.

How has online learning changed your work?

I have found it really difficult being away from the studio. I rely so much on friends for encouragement and honest feedback and it is difficult to communicate now they are scattered all over the world. We have self-organised crits amongst ourselves to try and counteract this. Also, I didn’t realise how important it was to be able to put up work around you in a studio. I’ve created a blog to try and replicate this virtually, and so that allows me and my tutors to look at all my work in one place.

What’s one thing that has helped you get through the past few months?

Apart from family and friends? Podcasts! I’ve used them to learn more about my field of investigation, espionage, and to distract myself from everything that is going on. My year has created a podcast to document our final projects and time in lockdown. It’s called ‘Hey, Listen, Something is Happening’. Let me know if you want some espionage podcast recommendations!

Rodrigo Costa, BA (Hons) Fine Art, Coventry University, UK

Where are you? Describe your work space.

In March I went home to Portugal, to Madeira Island. Here, I don’t really have a lot of space to develop my pieces and performances, which are usually larger than life. Luckily I have a sort of ‘office space’ in my room; this is where I spent weeks upon weeks, editing videos of performances I’d done before I left England, incessantly recording instrumentals and vocals of Portuguese children’s songs and scanning sketches, drawings, research and other relevant elements for assessment.

What is the name, theme, concept and final outcome of your graduate project?

‘A cabinet of wonders and a living room’ — it’s an unfinished installation piece, consisting of sculptures and videos. Cabinets of wonders were 16th-century rooms that housed diverse objects and artefacts from around the world. The original ‘cabinet’ I wanted to create grew from this idea, although it resides in the 21st century. It is primarily a reflection of my experience of childhood.

We have all had different experiences as children – some better than others. However, everyone shares one single concept of ‘childhood’: what it is and what it means. When entering this (physical/psychological) ‘space’ we are offered the possibility to be reminded of just that. There is something weirdly familiar about a particular colour or shape, a sound or a situation. Strangely recognisable nameless characters watch you while you watch them.

Originally, this ‘maze’ of repressed memories ended with the audience being invited into a smaller space that fitted about three or four people — a living room. There, they could stay standing, take a seat or — if they would allow themselves to break all social conventions of ‘normal’ behaviour — lie down.

On a small screen, the characters come to life. Hopefully, while standing, sitting or lying there, entranced by voices, melodies and movements, the fact that we are ‘adults’ (or ‘grown-ups’) inserted into a somewhat ‘childish’ reality would slowly sink in, as we were left wondering ‘whatever happened to this self?’. What I ended up creating, as an alternative to the final physical piece, was a virtual 3D model of what the space would’ve looked like.

Has the pandemic changed your graduate project? If so, how?

The pandemic and the consequent lockdown situation definitely affected the final outcome of my graduate project. The whole project had to be completely readapted to fit the ‘online’ limitations. The final installation had to be reworked into a 3D virtual model, which I made using Paint 3D (something I’d never used before…). I strongly believe my work is better received/enjoyed when experienced live. Although there is a somewhat big part of it that builds on from digital interfaces, it’s still mainly focused on ‘physically stimulating’ the senses.

Have you had to produce less work? Has this been a positive or a negative?The amount of work I produced during lockdown was similar to that of any other year, if not greater and more complicated. Having to show all the progress I’d made throughout a whole semester digitally wasn’t easy. It involved a lot of scanning sketchbooks, loose pages, scribbles, notes. Everything that would usually be handed in alongside studio work quickly had to be photographed before the university buildings closed down for an undetermined amount of time. As someone who surprisingly enough doesn’t use a lot of technology to execute ideas, this was a scary process. I wouldn’t class this as positive or negative, just stressful…

What do you wish someone had told you at the start of your graduate project?

There’s a pandemic coming. Hurry up and learn to use proper digital 3D software!

What are the most positive learning outcomes from this process?

Although this’ll sound extremely clichéd, one of the most positive outcomes I took from this process was that anyone can do anything, regardless of what and within any situation they’re put into. We were made to react, adapt and act. This whole situation also taught me how to think on my feet, to not expect somebody else to reach out to me, to reach out to others, to never stop creating regardless of what might be happening around or within you.

Shanique Brown, Caribbean School of Architecture, University of Technology, Jamaica.

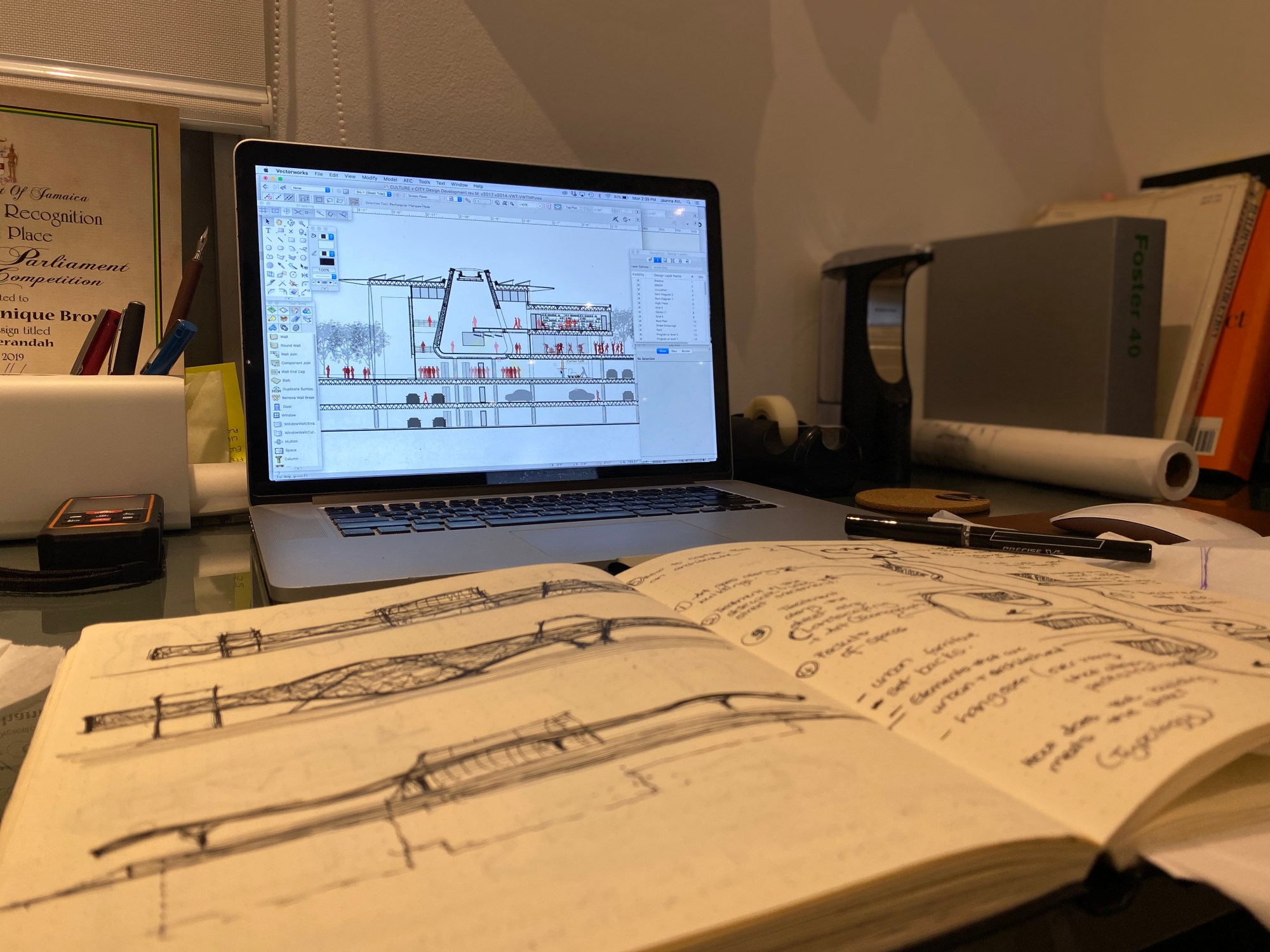

Where are you? Describe your workspace.

I was born and raised in Jamaica and I currently reside in its capital, Kingston. I work at a small desk in a corner of my cosy bedroom: surrounded with my books for details and inspiration as well as other tools to help me design, such as my sketchbook, pens, markers, sketch tissue and mock-ups and working models.

What is the name, theme, concept and final outcome of your graduate project?

My Project is entitled ‘[Dancehall] Culture + City’ and is based along the urban spine of Market Street in Montego Bay the capital of the parish St. James in Jamaica. Dancehall is Jamaica’s premiere street ‘theatre.’ It is an urban drama, a mature social movement that originated over fifty years ago. This nocturnal phenomenon emerged from the streets, the cracks, and margins, as it depicts the people’s survival story against forces of imperialism and systems of exclusion. It has materialised in a variety of distinct street dance events, music, dance moves, styles, and fashion, all the while effectively infiltrating the urban fabric of the city. Dancehall culture has the ability to take what exists in time and space, to occupy and create its own space in time for its theatrical, fluid, dynamic nature. This creates a dialogue, a relationship, between culture and the urban, and introduces elements of informality into an otherwise formal city plan.

Dancehall is a space that is liminal and contested. This project embraces the contested nature of dancehall by capturing Market Street, the urban spine of Montego Bay. The intervention seeks to create a dancehall ecosystem of inclusive and participatory spaces, where ordinary people can make a living in the dancehall industry. The ecosystem investigates how meaning is acquired through the occupation and use of a street, as well as the movement within it. The ecosystem transforms and adapts to the urban grain beyond codified planning regulations, which embodies the nature of dancehall, further creating culturally theatrical spaces of identity that critiques aspects of Western domination.

What’s one thing that has helped you get through the past few months?Knowing that if I pushed through and remained focused, I would complete the program and attain my Masters degree, making me one step closer to becoming a registered architect.

What are the most positive learning outcomes from this process?

The most positive outcome was that the online connectivity allowed for a larger audience for our critique sessions. The online sessions allowed for international architects and engineers to view and critique our work. This allowed for more feedback from a wider variety of people.

Romana Halgošová, BA, University of Fine Arts and Design in Bratislava, Slovakia

Where are you? Describe your work space.

I am in a living room. There are some prints, negatives, cameras and organised mess covered up with plants; the only free space on my working desk is a cutting board. The cat is sleeping in the other room.

What is the name, theme, concept and final outcome of your graduate project?

This project is called ‘F L U I D’ and it deals with the question of sexual identity. The audience is presented with a visual interpretation of gender via projection and installation. The projection is focused on one’s stereotypical perception of gender while the installation is challenging it. The idea is based on stereotypes emanating (not only) from visual arts and their inheritance in contemporary art and society. The final outcome is an installation that consists of an object that combines fragments of traditional sculpture, painting and historical photography. These fragments are partially destroyed by digital intervention and thereby the audience has the opportunity for their interpretation and exploration of gender problematics.

Has the pandemic changed your graduate project? If so, how?

Yes, it has changed it a lot. I like to work with space and my original idea was to turn a space into an interactive installation, where every step would change the projection frame. So when the viewer would come close to the object, they would suddenly be left only in empty space with this object and their own thoughts.

What’s it like working without your university’s technical support? Have you had to innovate left to your own devices?

I am quite familiar with bathroom developing but with historical techniques, especially with wet plate, it was bit of a challenge. Fortunately after the pandemic peak ended, the university AFAD was open [in special circumstances], so I was able to get in and use proper darkroom for making the final plate. Also our department was very generous about lending equipment, so I was able to get the data projector too.

Have you had to produce less work? Has this been a positive or a negative?

I think we were expected to produce approximately the same amount of work as usual, but in terms of taking pictures, I definitely produced less. Actually I produced no new images, the self-portrait you can see in the final work is a year-old photo I took in Madrid. Nevertheless, for me it was positive because I had more time to think about the whole project