I might owe my adult identity to Jessica Bendinger. The screenwriter’s credits include Aquamarine, What A Girl Wants and a number of Sex in the City episodes. Don’t forget the time-honoured First Daughter fronted by Katie Holmes, or the fact Bendinger wrote and directed the seminal gymnastics movie, Stick It. She inadvertently became a launching pad for young actors to paper the rooms of pre-teen girls. Bendinger’s the reason that several decades later — when the aforementioned stars have long-since become industry-acclaimed performers or tabloid fodder — we scour Instagram’s nostalgia sector, dedicated to breathing digital life into our bedroom posters once more.

Perhaps no Bendinger film is as memorable as that which turns 20-years-old this month, Bring It On. The 00s cheerleading classic not only informed my childhood, but structured it. I would ritualistically rewind the VHS (on two-day rental) to rewatch, once again, what was then considered an unadulterated portrait of Americana… it may have even contributed to my later immigration to the United States.

The irony is likely not lost on Bendinger that her concept for a cheerleading film which spawned five sequels and a Lin-Manuel Miranda-penned stage musical over the past two decades, took 28 different pitches to sell. Still, the near-constant rejection did not surprise the writer. While after attending competitions and camps, the writer clocked that the cheerleading industrial complex was an “insanely popular market,” she knew Hollywood to be slow on the uptake when it came to capitalizing on built-in audiences. Finally selling the idea after three months of pitching, she spent over a year drafting and revising the script for Bring It On. By 1999, the film entered production.

“Cheerleading is a wonderful proxy for lots of things in America and became the perfect Trojan horse in which to hide lots of cool stuff,” Bendinger explains of her attraction to the sport. “[Bring It On] was always a social satire. The movie was never a spoof of cheerleading — spoofs do not respect or love their characters. I both respect and love the characters in the movie.”

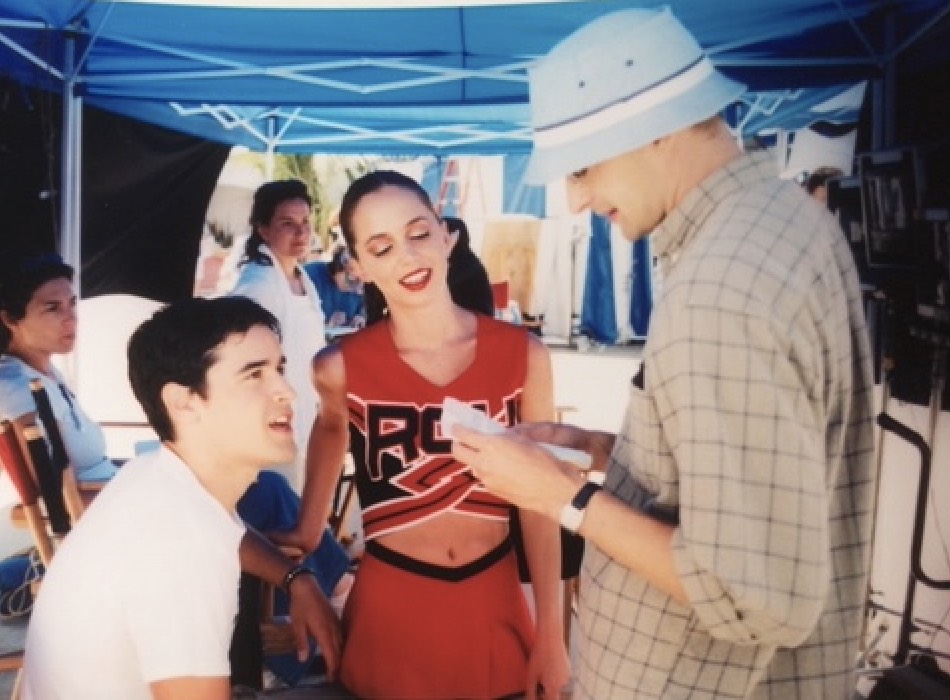

Led by Kirsten Dunst fresh off the success of The Virgin Suicides, alongside Gabrielle Union (who had recently starred in breakout hit She’s All That) as well as Eliza Dushku and Jesse Bradford, the film raked in nearly $100 million at the box office — eclipsing its budget almost ten times over. Attached early was Union, who would play the captain of the rival cheer squad, the Clovers: a group of Black and Latinx high school students from Compton, who eventually beat out the all-white, upper-middle-class San Diego Toros at nationals. Determined everyone involved would perform their own stunts, director Peyton Reed required each actor to participate in a four-week cheerleading training camp ahead of filming.

“It was an exciting time,” remembers Bendinger. “Gabrielle played Isis in the first reading we ever staged. And Missy was also played by Eliza Dushku at that same reading. So they were very much in the mix from the early days. And then we were lucky enough to get Kirsten and Jesse Bradford attached when we had the green light.”

Dunst had signed on to play the lead, Toros’ captain Torrance Shipman, before Romeo and Juliet heartthrob Jesse Bradford was cast as her love interest, Cliff Pantone. Reed had met with Bradford at a Venice Beach cafe and the two decided then that Cliff, like Bradford, would play guitar instead of the originally-scripted drums. Looking back, Bradford shares he was particularly excited that Cliff’s role as LA transplant and anti-jock was a “window to another world.”

“‘Uniqueness’ is a tough thing to describe, but it tends to foster staying power in any artistic field,” Bradford shares. “Besides the fact Bring It On’s funny, well-paced and an overall good movie by any standards, I think maybe there’s just something novel and unique about it. It kind of occupies its own space.”

The cast and crew watched in awe as the opening weekend box office numbers rolled in. It grossed nearly $20 million in its first weekend and became the number one film in the country for two weeks in a row. To Bradford, who was barely 21 when the film debuted, the response “opened a ton of doors” for him in Hollywood.

“Pretty sure I was at a Dave Mathews concert in New Jersey [on opening weekend] if you want to visualize me frolicking in ecstasy,” he shares. “Definitely the first film to put me on the map as an adult. I will forever be grateful for its impact on my career.”

Unfortunately, the critics remained dubious. “Not Much to Cheer About,” headlined one review, “Nothing New In Banal ‘Bring It On’” offered another. While the Times, both Los Angeles and New York, were kind, the Pulitzer Prize winner Roger Ebert proclaimed Bring It On “half Nickelodeon movie, half R-rated comedy.” It took almost a decade for Ebert to recant his review, later declaring Bring It On the “Citizen Kane of cheerleader movies” that “involved genuinely talented cheerleaders.” Bendinger appreciated Ebert’s revision, though it seems the initial avalanche of negative reviews didn’t necessarily surprise her.

“I knew that that was probably going to be a surprise to a lot of people in the film industry, given the decision-making that has informed legacy media companies and studios for decades,” she explains. “Movies are historically, and generally, not super ahead of the curve and that is not new news… [but] the audience has a lot to offer if you’re paying attention.”

The audience who subscribed wholeheartedly to Bring It On has now entered adulthood. They stream their old favourites on viewing platforms — that have since become studios in their own right — and lament the death of the earnest and ever-entertaining ‘romantic comedy’ of the new millennium. Bradford believes romcoms aren’t as frequently released now due to the sophistication of 2020 audiences, but Bendinger is convinced studios are simply underestimating the power of the genre.

“As media has become an on-demand product, the movie business has suffered in terms of its ability to keep up… Making originals in perennially-beloved genres is a smart move.”

The effect of the film on Bendinger’s writing career cannot be understated. For the past 20 years, the phrase, “From the writer of Bring It On,” has served as a promotional preface for every one of her subsequent ventures. While many would resent the near-constant association, or try and write their way out from under the Bring It On shadow, Bendinger embraces it.

“When you create movies that people know, chapter and verse — especially when they’re outliers that were developed outside the system and over-performed — that is very gratifying.”

It’s the overall message of Bring It On that Bendinger believes greatly contributed to the film’s continued fandom. While its racial inclusion — especially among primary characters — already put the film far ahead of its time, the dynamics of social strata woven throughout the tapestry of Bring It On allow it to hold up so well 20 years later. By wrapping its arms narratively around “not only people of colour, but queer kids and kids who might feel othered,” Bendinger says Bring It On offered the overlooked and ostracized the chance to see themselves on screen.

Bradford credits the film with palatably articulating minority exploitation to its young viewers. “[The movie] managed to shine a light on problems like appropriation and white fragility… in light of recent history, Bring It On seems relevant right now,” Bradford claims.

The fact the Toros consistently won the national title by stealing choreography from a team that couldn’t afford to compete reinforced an uncomfortable reality: white people often only feel the sun by standing on the backs of people of colour. For me, a lower-middle-class six-year-old from a white-majority country in the Southern hemisphere, this would be the first time I had glimpsed true systemic inequity. By dressing it up in navel-baring tennis skirts, Bendinger was able to address the intersection of race and class head-on: suffusing universal truths into catchy cheers.

Of course, at its conclusion, the Clovers’ incomparable talent sees them emerge on top — a testament to what people of colour can achieve on a levelled playing field. It was poetic justice, neatly packaged into a teen magazine’s centrefold, and ready to take prime position above an adolescent’s bed.