“It all started with a photograph of my mom,” says designer Huy Luong, one-third of New York-based label Commission. He’s speaking, specifically, to the inspiration behind the brand’s most recent, autumn/winter 20 outing, but his words could also serve to outline the brand’s origins. After meeting in 2017, Luong, alongside co-designers Jin Kay and Dylan Cao, began discussing their shared East Asian heritage, and its lack of true representation within Western fashion. Think the stereotypical cheongsams, dragons, cherry blossoms. A year later, the trio founded Commission, as a means of bringing East Asian culture to the industry’s table in the most genuine, nuanced way. “Our approach has been to make sure that everything is super personal,” Cao says. “That’s where the conversation of our moms started. It’s a lived experience. We grew up living with those memories. So, for us, that was the most authentic starting point.”

Cao and Luong grew up in Vietnam, and Kay in South Korea. Pursuing their burgeoning interests in design — Kay’s penchant for art and drawing; Luong’s infatuation with Project Runway — they each moved to New York City to attend Parsons School of Design, before taking office jobs at some of fashion’s most prestigious houses. It was these stints — some freelance, some full-time — that would serve as the namesake for their label. In 2017, when the three designers met at a mutual friend’s birthday party, they found common ground not only in their shared culture, but in their desire to strike out on their own. “At that point, I was still working nine to five at other companies. I thought maybe one day it would happen, after I’d climbed the corporate ladder,” Cao says. “I was just over working for other people.” A year later, the trio decided instead of being commissioned by others, to finally commission themselves. And the label was born.

“The idea of the late 80s and 90s East Asian woman is at the core of the label,” Cao says. A dip into Commission’s immaculately-curated Instagram feed speaks to these roots: the suited heroine of Edward Yang’s Taipei Story; a Keizō Kitajima portrait of a woman in a mohair-haloed sweater. And, of course, the vintage photographs sourced from friends, followers and the designers, themselves. “We talked a lot about how we grew up seeing our moms dressing up,” says Cao, of discussions surrounding the label’s inception. “And they would always look so put together.”

The three designers grew up between the 80s and 90s, as an unprecedented number of women began entering the workforce in East Asia. “So, the corporate look is a very essential part of our silhouette,” says Kay, describing the label’s signature pant suits and skirt suits, in matching wool suiting. Behind the put-togetherness, however, is always a bout of humour — “mixing kitsch with sophistication” — or a sentimental detail. This is what makes the world of Commission feel so rich, so salient. “The fabrics of that time, if you weren’t affluent enough, would be some kind of polyester that doesn’t wrinkle. No matter how much you sit or ride motorcycles, it will always be straight, flat and perfectly ironed. There’s a certain irony to that,” Cao says. “We enjoy a sense of contrast in the way we work.” Fittingly then, the waistband of a leather skirt is sewn with a fanny pack-esque pocket, a nod to the ones Cao’s mother wore to facilitate her motorcycle commutes in Vietnam. A secretary dress is printed with florals drawn from the tablecloths and wrapping paper of the designers’ youths. “We take prints from very mundane everyday objects, which are really of their era,” Cao explains.

The trio are not, however, merely recreating these vintage pieces sourced from photograph or memory. “We want to take those elements and make them ‘today’ — what a modern woman would wear,” Kay explains. The wrinkle resistant suits of decades past are reimagined in fine wool suiting and fabricated in some of the industry’s finest mills. Same goes for the label’s signature seasonal patterns, which are always custom-designed by Luong, and printed in the factories that printed Hermès’ famous silk scarves.

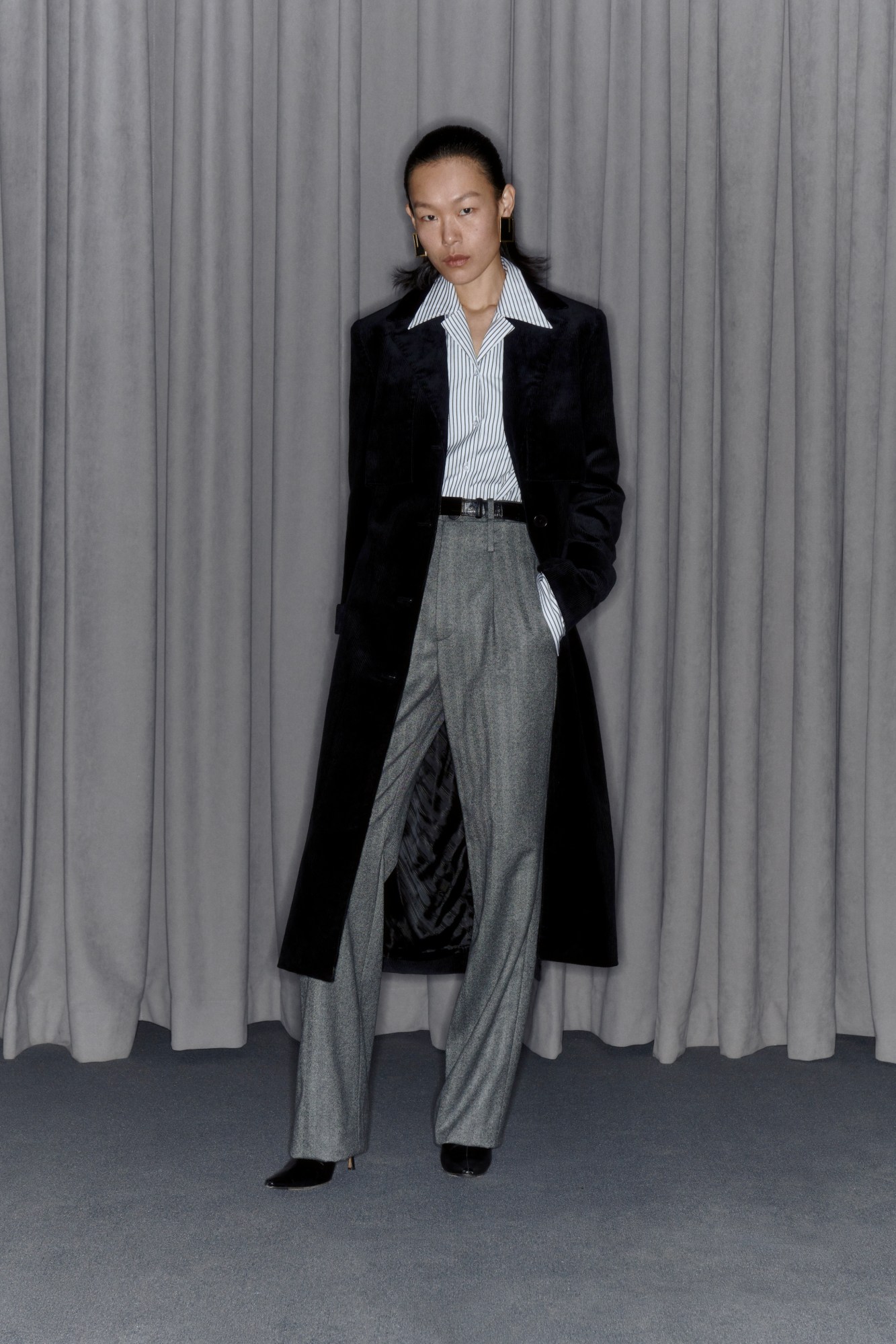

Commission’s AW20 outing perhaps best embodies how the label revels in juxtaposition. The collection was inspired by a photograph of Luong’s mother, singing on stage at his family’s restaurant, a venue that hosted casual dinners, corporate events and weddings. “My mom worked a heavily corporate job that would have gatherings at venues like the one Huy’s mom owned,” Cao says. “We wanted to explore that contrast, where the woman is dressed for work and would wear the same look on a night out, everything’s velvet-y and has a glam feel to it.” Blue and white striped shirts worn with fur stoles and red leather gloves; electric satin blouses worn with herringbone trousers; a snow leopard-patterned set — custom designed by Luong. “We wanted to recreate those fuzzy mohair knits that are usually very itchy and uncomfortable, with the hair that falls out. But we wanted to elevate that kind of look. So, we developed a technique with Japan and use 100% cashmere, so it’s ultra soft,” Kay says.

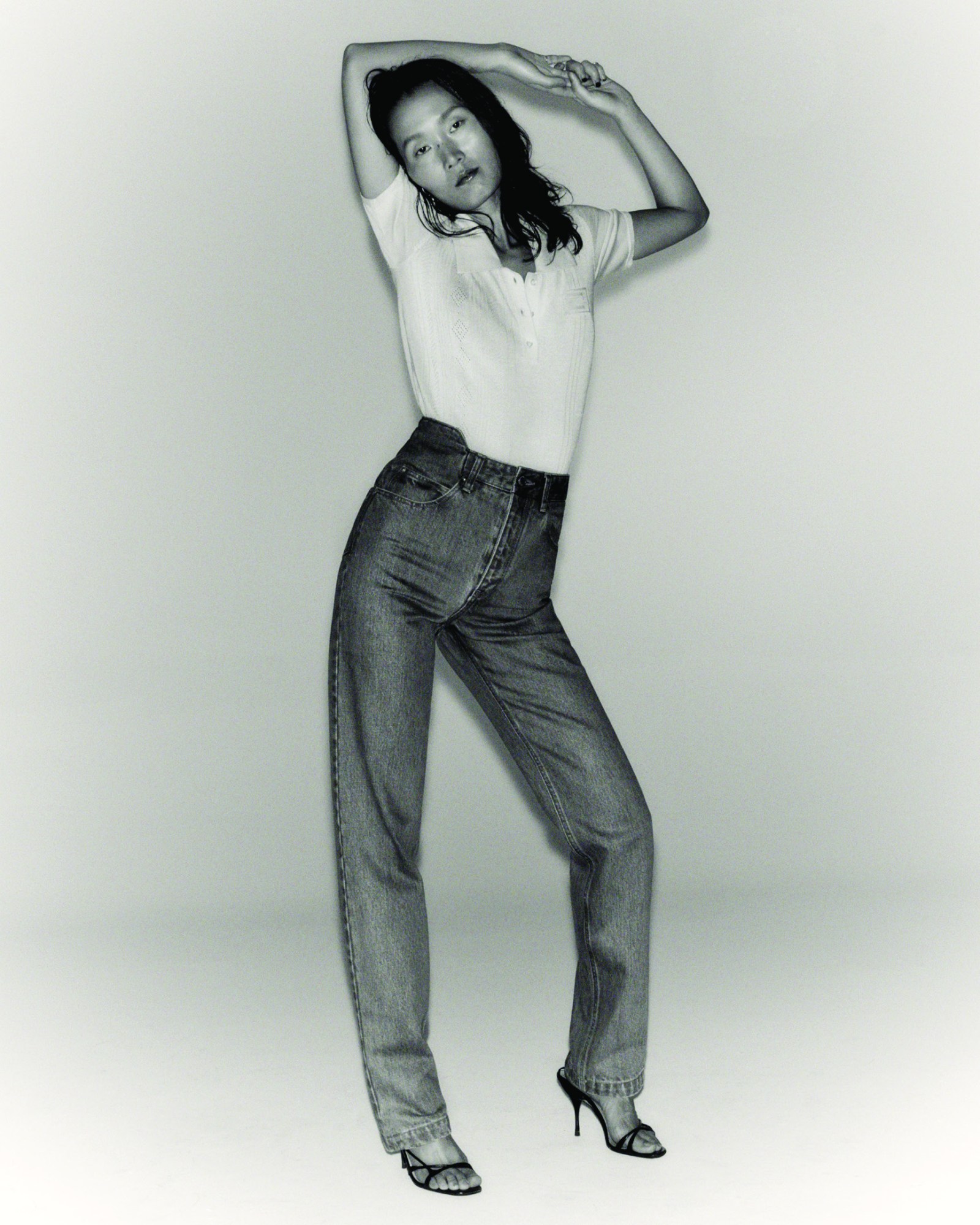

The brand’s denim capsule — launching on August 13 — exudes the same playful refinement. “Denim was a crucial part of the wardrobe, back then,” says Kay, on how the new category plays into the label’s distinctive aesthetic. For one, each pair is crafted in Japan of the highest quality Japanese denim. To give their jeans the signature “Commission look”, the designers dug back into their archive, referencing the fanny pack waistband of seasons past, streamlined down to the topstitching. “It looks very simple from afar, which was our intention, but up close there is intense craftsmanship and detail.”

In addition to the clothing, the richness, the life that surrounds Commission overflows into two parallel photographic projects, Commission Femmes, and more recently, Commission 1986. “The beauty in Commission Femmes is that it was a really organic process,” recalls Cao, who explains that in the label’s early days, they would invite Asian friends and acquaintances to come view and talk through the collections. Luong would take informal photographs of their visitors wearing the garments, against a white wall. “After a while, it became a body of work. When you take one photograph at a time, it feels like a routine. But when you look at a wall of 50 photos, you start to see the modern-day Commission woman,” Luong says. Of the project, which is still ongoing, and has become a crucial part of the label’s visual lexicon, Kay says, “We wanted to celebrate Asian women in a very non-artificial way, with the people around us, friends, not just models on a runway.” And tying the project into Commission’s ethos: “We’re not making fantasy clothes for Instagram or the internet; we’re making real garments that women can live in.”

Commission 1986 began much more serendipitously, during the ongoing pandemic and stay-at-home orders. “It’s really an accidental project,” Cao says. “During quarantine, many of our friends were at home spending time with their families and going through family albums. We got a lot of random texts from the women we knew saying, “My mom looks so Commission here,” or “Commission moment!” And they’re such beautiful and personal photographs, each mother is so distinct and special.” The trio decided to amass and showcase all the photographs in a single, dedicated space. To the designers, the 1986 project also took on another ramification of post-coronavirus America, not quarantine, but anti-Asian racism. “Around [the time we started Commission 1986], racism against Asians was rising in the states due to COVID-19. We’re all Asian, and we know we’re all from different countries, but to many people, we tend to be grouped together. Through these photographs, discovering the family histories in different countries and cities and eras, we wanted to show that we’re not all the same,” Kay says.

The lush and highly personal world of Commission continues to grow and expand. The designers are especially excited about their upcoming spring/summer 21 collection, for which the previous collection “set a solid framework,” Cao notes. “As we evolve we want to expand the narrative of the brand. We want to make room for other ideas to develop, to allow ourselves to be inspired by all these sources as well,” he continues. “But you will always see the image of our mothers.”